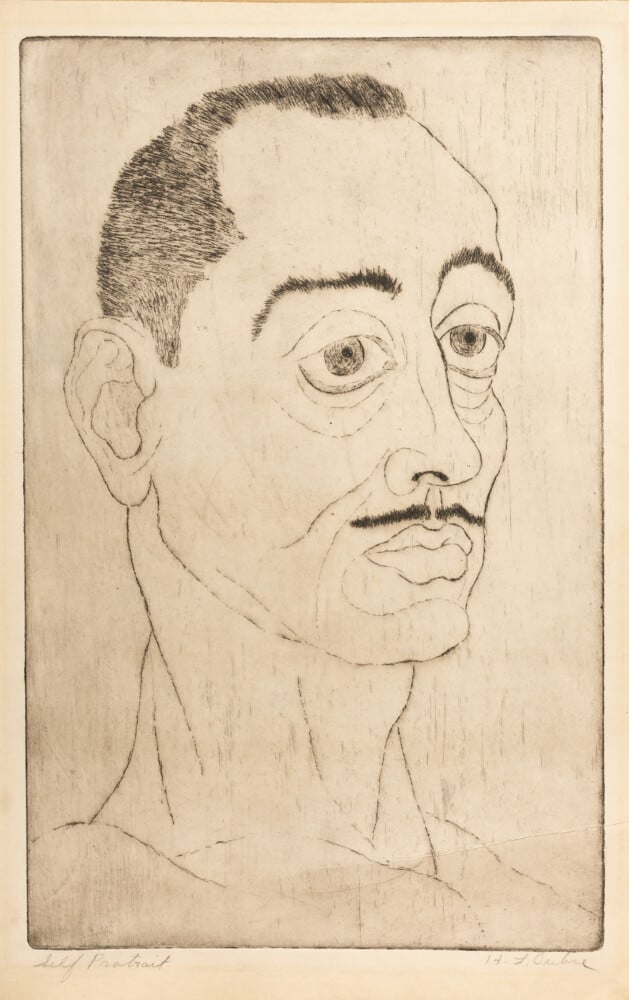

on paper, 26 1⁄2 x 20 3⁄4 in. (framed), The Paul R. Jones Collection of American Art at The

University of Alabama, PJ2008.0925. Image by Lily Brooks and courtesy of Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham.

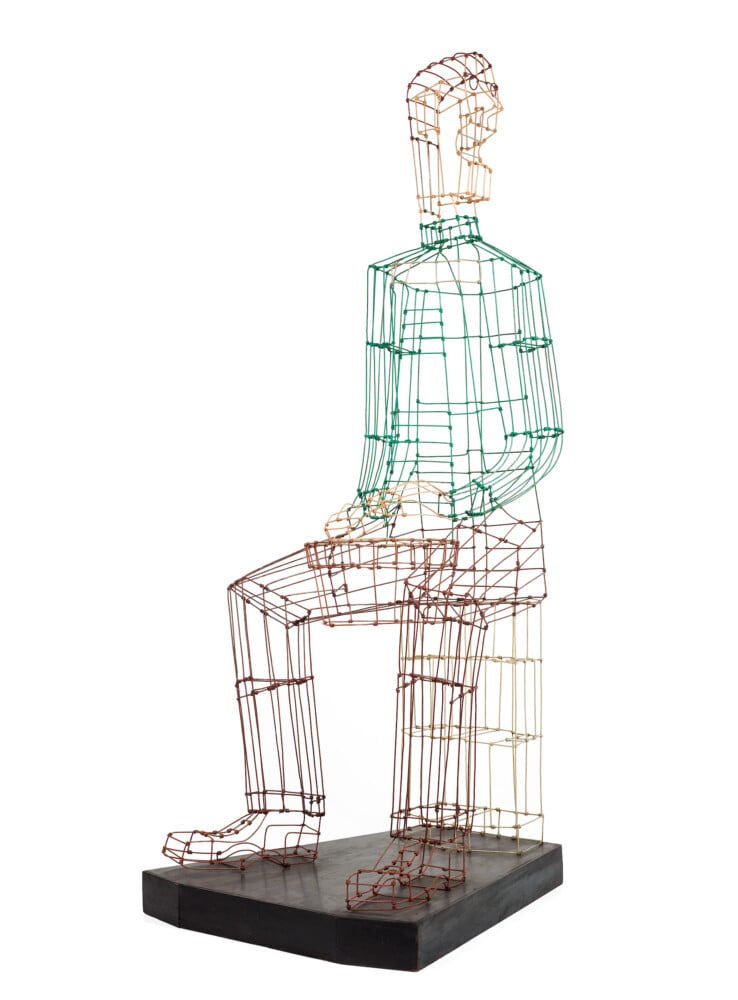

The Hayward Oubre retrospective at the Birmingham Museum of Art, Structural Integrity, serves as revelation and rectification. This exhibition brings overdue recognition to a pioneering artist whose legacy has largely lingered in obscurity, reflecting Oubre’s unwavering commitment to artistic innovation amid societal challenges. Known primarily for his wire sculptures, Oubre saw endless potential in all materials, echoing the layered complexities of his identity as a Black artist in the Jim Crow South.

Oubre’s life and art embody a quiet resistance. Born in New Orleans, he was shaped by his Creole heritage and a drive to push boundaries, yet his work was often excluded from mainstream movements and overshadowed by white contemporaries. In 1941, Oubre enlisted in the U.S. Army and was deployed to Alaska with the segregated 97th Regiment, where he served as a master sergeant and structural draftsman on the Alaska-Canadian (Alcan) Highway, a project initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt after the attack on Pearl Harbor.1 Constructed primarily by Black engineers within a year, this 1,500-mile highway through uncharted terrain instilled in Oubre a personal ethos centered on fortitude, labor, and precision, all of which influenced his artistic approach.

The exhibition title, Structural Integrity, captures Oubre’s artistic philosophy and character. For Oubre, structure brought balance and durability—qualities particularly meaningful given the lack of recognition he received during his lifetime. Upon entering the exhibition, visitors are greeted by a beautifully made raw wood pedestal with a grounding base and a visual timeline. This pedestal holds two wire sculptures, a painted plaster, a carved wood sculpture, and an oil and acrylic painting on canvas. Through his varied materials and subjects, Oubre achieved stability that mirrored his journey as a consummate educator exploring diverse media.

Carolina. Image courtesy of the Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham.

Oubre’s sculptures, often made from humble wire coat hangers, radiate strength. His experimentation with wire began in the 1950s during his tenure at Alabama State College, where he transformed it into an innovative medium. Pieces like Eternal Flame (1963) were constructed in memory of President John F. Kennedy and reveal his engineering prowess.2 Using only pliers and his hands, Oubre shaped flames from twisting metal strands, mimicking fire’s wild, erratic gestures. Some wires coil tightly to resemble intense, concentrated heat, while others arc outward, capturing the flickering energy of flames leaping into the air. Though the flames are frozen in time, Oubre painted them red, green, and yellow, imbuing them with life and energy. The open structure allows air and light to flow, giving the sculptures an ethereal lightness and transparency.

Oubre’s Radar Tower (1960) reveals how Oubre’s engineering interests intersected with his appreciation for technology’s evolving role in society. As a former Army engineer, he was well-acquainted with the use of radar during World War II and took inspiration from this cutting-edge innovation. Radar Tower features a vertical lattice structure that climbs skyward, representing the presence of radar systems designed to “see” beyond ordinary perception. Usually, at the top of the tower, the circular radar dish or antenna is found. The tower twists in unexpected directions in Oubre’s hands, suggesting a figure embedded within, emerging from abstraction. A hint of snaking arms, the foundation of a torso, and an orbital head. The piece symbolizes Oubre himself: the problem-solver who uses science, mathematics, and creativity to elevate everyday materials into powerful expressions of ingenuity. These works function as “drawings in space,” blending line, form, and volume to create three-dimensional compositions. The spaces between the wires hold as much meaning as the wires themselves, forcing viewers to consider what is present and what is absent.

Through his varied materials and subjects, Oubre achieved stability that mirrored his journey as a consummate educator exploring diverse media.

Despite a deep commitment to his craft, Oubre was equally dedicated to teaching, with a career that spanned HBCU institutions such as Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes (now Florida A&M University) in Tallahassee, Alabama State College (now Alabama State University) in Montgomery, and Winston-Salem State University in Winston-Salem. Though he had connections to New York galleries, he intentionally chose to stay in the South, immersing himself in a network of remarkable HBCU professors, artists, and alumni.

In 1966, as a teaching tool for his students, Oubre created and copyrighted A Concise Study of Color Mixing and Color Relationships, which he saw as an update to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s foundational concept on color theory with Theory of Colors (Zur Farbenlehre) from 1810.3 In the Structural Integrity’s presentation of Oubre’s paintings from the 1960s, his background in color theory comes to life with vibrancy and motion.

Causing Sonic Booms, 1961, acrylic and acrylic resin on canvasboard, 26 x 22 x 2 1⁄4 inches,

Collection of Norm and Carnetta Davis. Image by Erin Croxton and courtesy of Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham.

resin on canvas, 30 x 24 inches, Collection of Carla and Cleophus Thomas, Jr. Image by

Erin Croxton and courtesy of Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham.

These paintings simultaneously broke down objects into geometric shapes and presented them from multiple perspectives. A Missile Breaking the Sound Barrier Causing Sonic Booms (1961) was completed during the Cold War and embodies the tension of the era. The painting portrays a sharp arrow as a missile speeding through the turbulent sky, piercing circles that echo a sonic boom. The missile is swift, precise, and unwavering as it zeroes in on the target ahead, a dark planet, a black hole, the unknown or unknowable. Here, Oubre’s fascination with the technological and scientific boom of the early twentieth century merged effortlessly with capturing the anxieties of a world on the brink of nuclear warfare.

In contrast, Equilibrium (1969) offers a serene, reflective experience with concentric circles and rings that radiate outward, symbolizing interconnectedness across time and space. The title suggests a pursuit of balance amidst life’s chaos—a recurring theme in Oubre’s artwork. The painting’s vibrant colors and dynamic forms create a sensory experience, drawing viewers into a world of harmony and movement.

Though he rarely exhibited outside of the South during his lifetime, Oubre had tremendous success with the Clark Atlanta University Galleries yearly juried competition, which became the Atlanta University (AU) Annual.4 These exhibitions provided Black artists a national platform to compete during a time when Jim Crow laws barred interracial competitions. In 1956, when Oubre submitted his first wire sculpture titled Proud Rooster (1956), he was frustrated when the work was rejected; he vowed to return the following year. When he did, he took first prize with an instantly recognized, powerful, and minimalist representation of Jesus in his work titled Crown of Thorns (1957). 5 His form is suggested by continuous, flowing lines that gracefully capture the essential features, as a crown is formed from thin, twisting strands of wire that encircle his brow.

Johnson Collection, Spartanburg, South Carolina. Image courtesy of Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham.

In Birmingham, Verily I Say Unto You (1957) hangs nearby, a pencil on paper drawing of a slender and lean Jesus with pronounced, angular cheekbones and a gaunt, narrow face that exudes intensity. His hair is tightly coiled and flows around his head in dense, intricate curls that cascade down, giving a sense of a wild, yet intentional, texture. The focal point is his long, thin finger, pointed upward in a gesture that directs attention to his large, wide-open eye, which holds a piercing, almost otherworldly, gaze.

The broader significance of Structural Integrity extends beyond the museum walls. It acknowledges that overlooked artists, like Oubre, played a pivotal role in shaping American art history. His work spans historical eras, bridging the social realism of the New Deal with Postwar Abstraction, all while drawing from a visual language deeply rooted in Black history and identity. Traditionally marginalized by the art world, voices like Oubre’s are often confined to narrow definitions, yet his work defies such limitations with a spirit of resistance and versatility.

During his years teaching at Alabama State College from 1949 to 1965, exhibitions at institutions like the Birmingham Museum of Art were inaccessible to Oubre and his students due to segregation. This underlines how the current exhibition also serves as an acknowledgment of the systemic barriers that prevented his work from reaching a wider audience during his lifetime. By centering Oubre’s legacy, the Birmingham Museum of Art offers a long-overdue recognition, illuminating an artist whose work resonates with profound cultural and historical importance.

One cannot help but consider the weight of Oubre’s trajectory. Oubre’s life and practice were marked by an indomitable spirit, from constructing military supply routes in extreme conditions to bending wire into abstract forms. His work shows the enduring power of an artist who chose to stay in the South, working within its limitations while pushing back against them. Structural Integrity presents, not just the work of an individual artist but a testament to the importance of resilience, recognition, and the pursuit of artistic freedom.

[1] Richard F. Weingroff, “America’s Glory Road,” Public Roads, Federal Highway Administration, Autumn 2017, Vol. 81 No. 3.

[2] President John F. Kennedy’s memorial and gravesite at Arlington National Cemetery is marked by an “eternal flame.” “President John F. Kennedy Gravesite.” Arlington National Cemetery. Accessed January 8, 2025. https://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/explore/monuments-and-memorials/president-john-f-kennedy-gravesite.

[3] Hayward Oubre. The Johnson Collection, LLC. (n.d.). https://thejohnsoncollection.org/hayward-oubre/.

[4] About cauam. Clark Atlanta University. (2024, September 30). https://www.cau.edu/about-cauam/.

[5] Langly, Jerry, “The Intersecting Art Worlds of Floyd W. Coleman and Hayward L. Oubre,” Catalog for Rhythmic Impulses: The Art of Floyd Coleman and Hayward Oubre, University of Maryland University College Arts Program Gallery, 2018.

Hayward Oubre: Structural Integrity at Birmingham Museum of Art is on view through February 2, 2025.