I first saw Joy Drury Cox’s Applications and Forms drawings in the 2019 Atlanta Biennial: A thousand tomorrows at the Atlanta Contemporary. In the saturated space of a large group show, Cox’s drawings were quiet and austere, but insistent. I returned multiple times to contemplate a familiar eerie sense as I pieced together their real-world references. Her work is at times sly, poking at and playing with minimalist structure, with an intuitive and meditative approach to form. The drawings evoke ghostly, empty spaces on the white page opening the underlying structures of legal identities, civic engagements, and financial possibilities. Through erasure and redaction, they accumulate layers of significance.

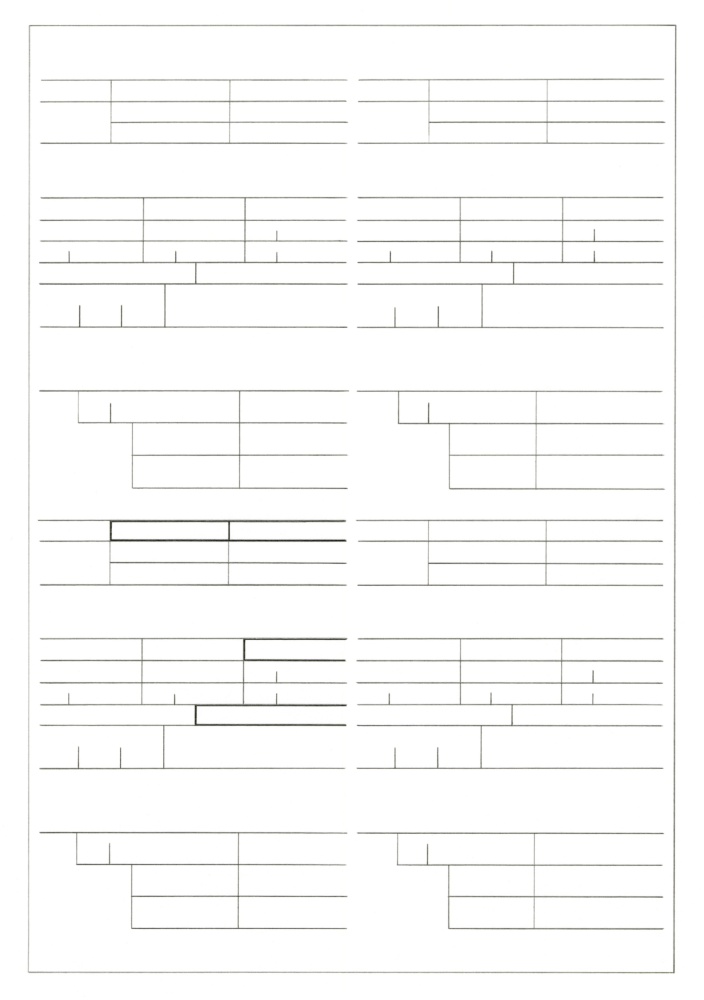

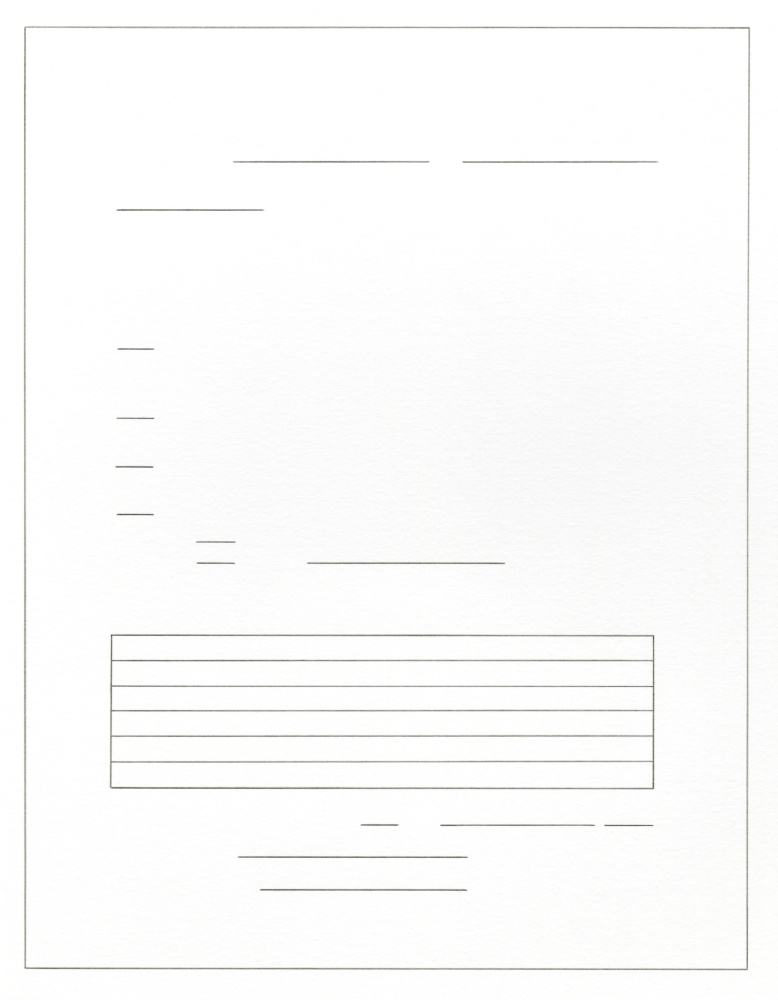

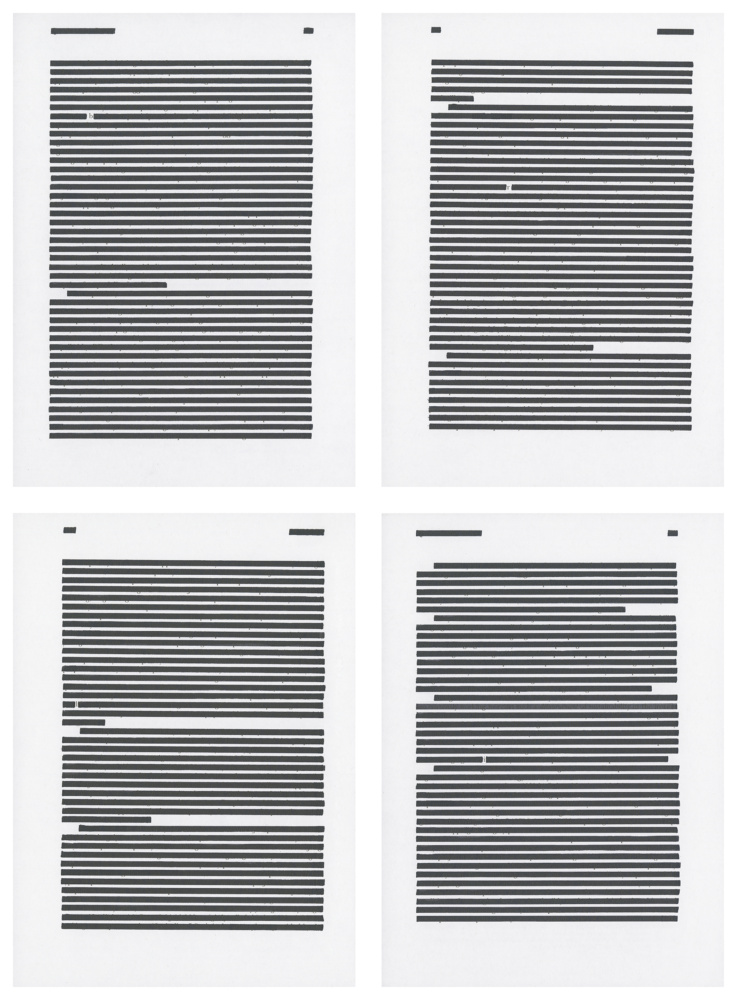

Each series unfolds in two stages. Completed between 2005 and 2006, Cox replicates job applications from chain retail stores and fast-casual restaurants. From 2007 to the present, she has expanded the series to encompass a wide range of bureaucratic documents. These works evoke lived narratives and personal connections to birth, death, and marriage, while also referencing labor relationships found in timecards, secretarial memos, and customer receipts.

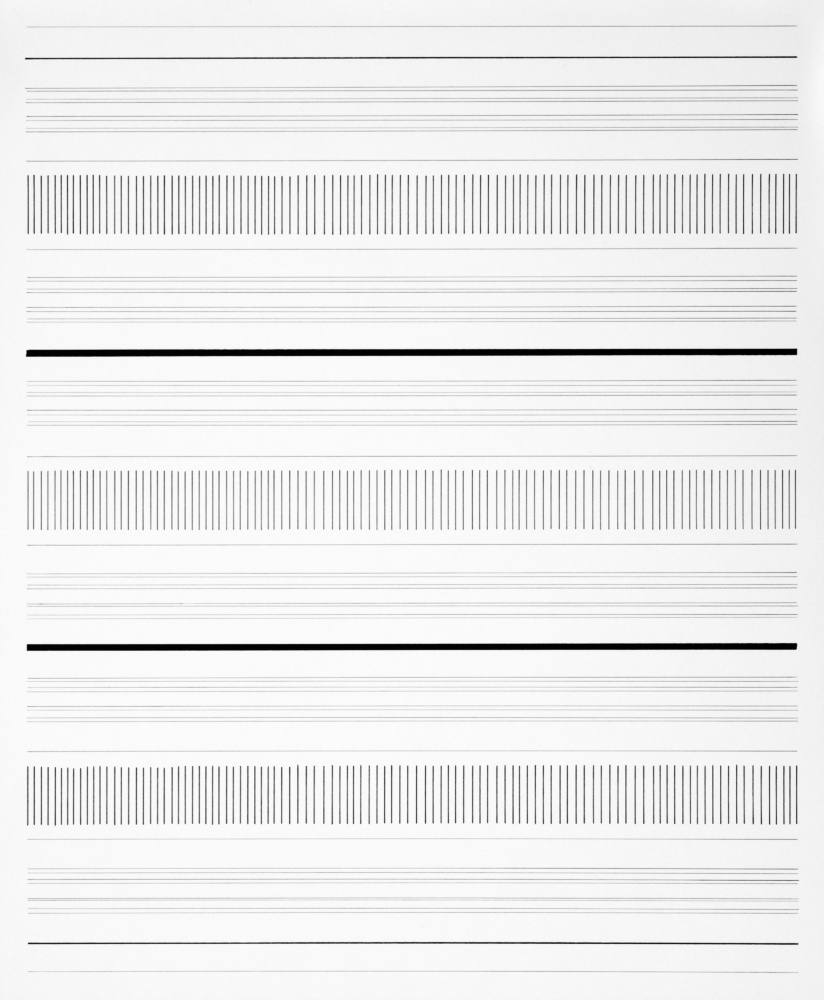

Stripped of all data and text, each drawing precisely duplicates the source form’s structure and scale. Using a mechanical pencil and braced by a straightedge, the lines show only the faintest trace of the artist’s hand, though some titles and notes hint at biographical connections. In the series, a tax return, 2009 W-2 Wage and Tax Statement (One Page – 4 part), (2010), is found alongside a premarital education form, State of Georgia, Certificate of Completion of Qualifying Premarital Education, 2018. A Waffle House job application might appear beside a birth certificate whose filing date matches the artist’s own year of birth. And the anonymity of Certificate of Death, State of New York contrasts with the one bearing a family name in Certificate of Death State of Georgia (for Beth Drury), both from 2007. Imagining a biographical narrative around these titles is partly the appeal.

By removing all printed or handwritten content from the source document, Cox reveals the architecture of the page—the design of the thing—while foregrounding the ways such forms shape civic identity. The boundary of the form itself is a placeholder for the body. Individuals are compressed into a grid of boxes, blank spaces, and designated fields. The viewer anticipates the categorical limiting behind each imagined question, the narrowing of choices, and the prescriptive box ticking. These identifying records mediate relationships between consumer and purveyor, and individual and institution. Each form promises order and legibility as individuals are reduced to hollowed, standardized fragments. Erasing what was handwritten becomes an intervention of its own. Cox erases the idiosyncratic to underscore the narrow, pre-determined spaces allotted for the personal. To reintroduce these forms as a hand-drawn objects is a commitment to a kind of dark humor, an Andy Kaufman–like gesture that exaggerates the futility and absurdity of replicating bureaucracy by hand.

Meaning in Cox’s projects shifts even further as the delivery systems of her source materials have undergone rapid change in recent years. The physical objecthood of the application forms, along with the technologies and systems that produce office paper pads, triplicate certificates, and licenses complete with identifying personal numbers, has been evolving at a slow and measured pace for nearly a century. Finding affinity in analog, Cox is not interested in foregrounding digital technology. Yet within the timespan of her project, access to these forms has shifted decisively from paper to screen. In less than a decade, manually typed and handwritten documents have become auto-filled webpages, a digital driver’s license is now valid, and a ticket from a takeout order might arrive via text message. Spaces that once accommodated the particularities of handwriting are increasingly flattened by uniform fonts and stylized preloaded signatures. The digitization of forms has eliminated the possibility of the handwritten altogether. A whiplash nostalgia for a fading material world pervades.

The loss of tactile analog access intersects with broader patterns of information control. Redaction and erasure have long served as tools of the state, determining what information reaches the public. Many of Cox’s source documents are products of government administration, structured to regulate civic life and codify identity. Her 2018 drawing Free Community Water Analysis Test Form from The American Clean Water Program once referred to the routine possibility of requesting public water safety information, perhaps already shadowed by anxieties around unequal access to clean water. By 2025, however, the work reads differently. The drawing’s emptied spaces carry an uncanny prescience, seeming to have anticipated a broader removal or limiting of access to available datasets and published scientific research. Over the past year, information once publicly available has been increasingly restricted or removed, a reminder that erasure shapes what can be known.

Erasing what was handwritten becomes an intervention of its own. Cox erases the idiosyncratic to underscore the narrow, pre-determined spaces allotted for the personal.

Cox’s earlier engagement with blackout in her 2010 work October Breadlines similarly illustrates the dual function of redaction as both concealment and revelation. In this project, she blacked out ten pages of October magazine, leaving only the letters to spell “breadlines.” The magazine’s intellectual labor of ideology and theory competes with an invocation of lived histories of scarcity, from Depression-era hunger to Soviet distribution systems and the food lines that reemerged during Covid-19. Cox’s use of blackout aligns with broader artistic and poetic strategies that employ erasure and redaction to reveal what might otherwise remain unseen with established structures. Early examples of blackout works, like Tom Phillips’s paintings and drawings over the pages of Victorian-era novels, don’t engage the tightly controlled visual language of state censorship that we might associate with Austin Kleon’s blackout newspaper poems or Alexandra Bell’s journalistic interventions. Both methods of redaction—blackout and erasure—juxtapose the sanctioned authority of the published form with the unsanctioned mark of the individual’s intervening hand. In civic language, erased and obscured lines remain familiar as forms of redaction, but for Cox and other artists they become tools of inversion and critique.

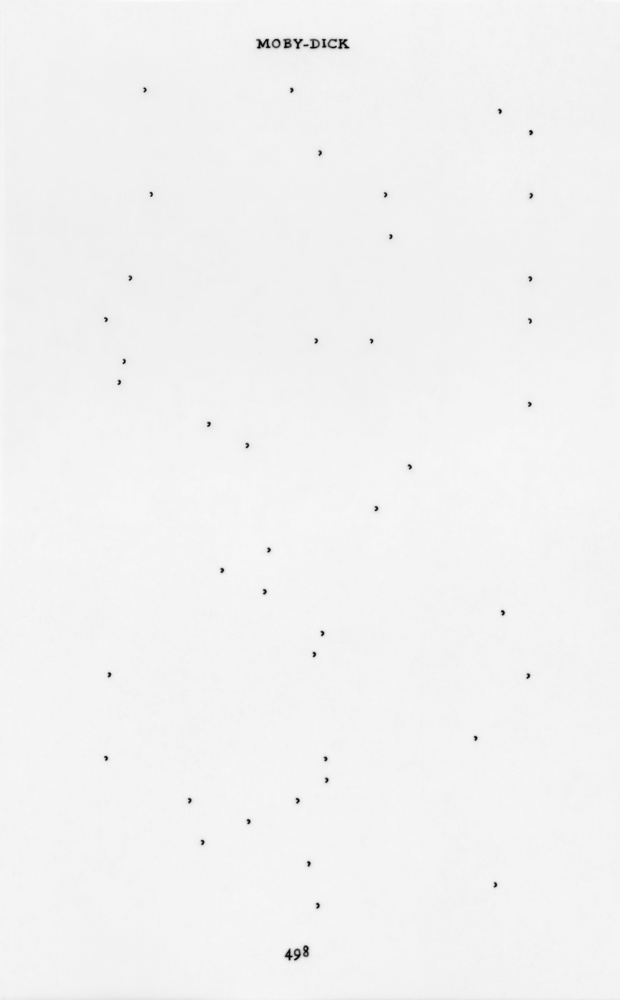

Cox’s use of poetic erasure is evident in her 2006-2014 series Punctuation Studies where she silences canonized authors while giving faithful care to their punctuation. Moby-Dick, for example, is rendered page by page through hand-drawn transcriptions of every comma in Melville’s novel. By stripping away the words and preserving only the punctuation, she highlights the skeletal framework of the text, emptying and reanimating the language structure. This approach situates Cox alongside poets such as Tracy K. Smith and M. NourbeSe Philip, who also use historical documents as source texts transformed through absence and fragmentation. Philip’s Zong! (2008) cuts and reassembles letters and words across blank fields to generate new cadence, while Smith’s Declaration (2017) retains the original spacing of its founding text, keeping it parallel. Like these poets, by reconfiguring existing texts, Cox makes absence generative and expressive.

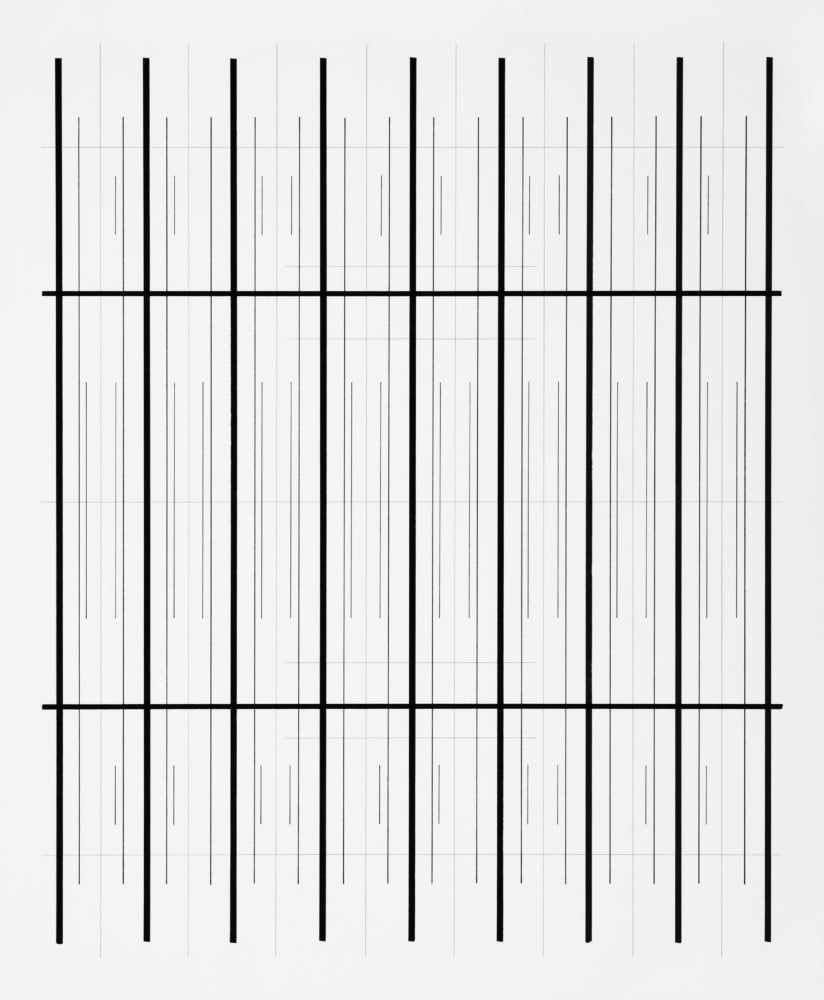

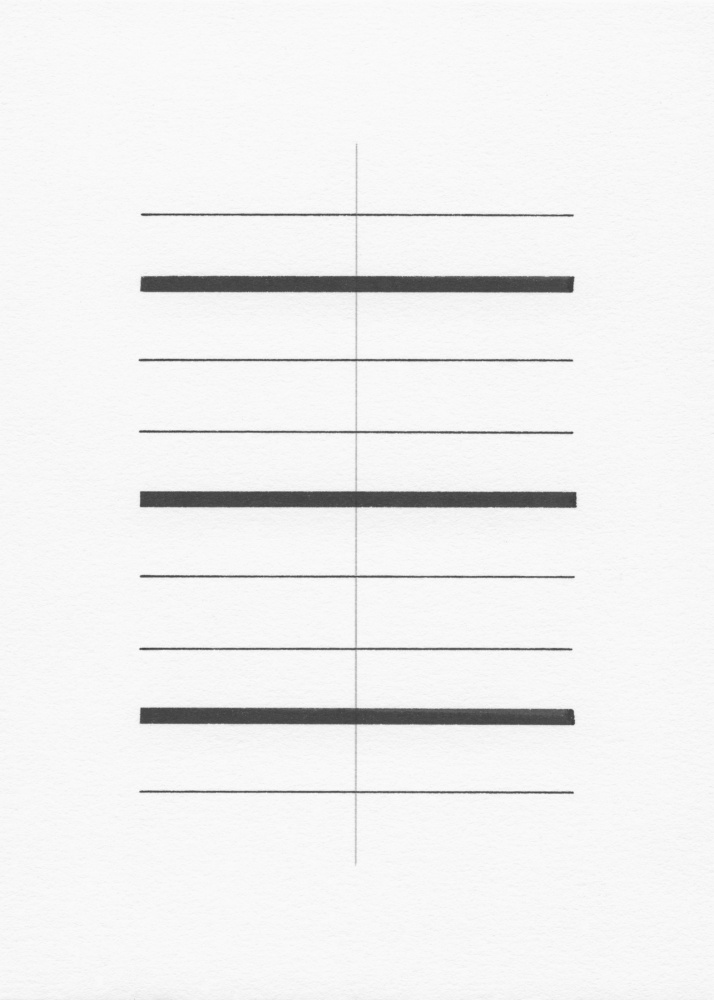

Not all of Joy Drury Cox’s work includes appropriation. Her visually rhythmic series Prone and Plumb (2019–2020) is a more intuitive exploration of formal constraints. Each drawing has a palindromic title, reinforcing the visual symmetry and balance at play in the compositions. The forms speak in the rectilinear language of industrial design with straight lines, right angles, and measured divisions. This architectural sensibility is rooted, in part, in family history: Cox’s maternal grandfather Jim Drury was a structural engineer who worked with Atlanta Neo-futurist architect John Portman for several decades. Designing with weight, load, and equilibrium in mind was something Cox encountered early, shaping an awareness of how line, proportion, and repetition hold space. While Prone and Plumb is rigorously constructed, it retains a meditative quality, calling to mind Agnes Martin whose grids and delicate lines merge structure with emotional resonance. Cox’s drawings weave inherited technical precision with an intuitive hand.

Across her projects, Joy Drury Cox employs repetitive, meticulous actions that verge on ritual. Whether replicating bureaucratic forms, redacting text, or tracing punctuation, her precise rigor is coupled with deadpan delivery. Her work is discreet and meticulous, arch and absurd. Over time, Cox’s works have accumulated multiple, interwoven interpretations, showing how institutional, civic, and linguistic systems both support and constrain. At a moment when multiple US government agencies are increasingly redacting and removing information, Cox’s interventions gain urgency. Her practice moves beyond nostalgia for analog technologies or the aesthetics of absence into a sustained inquiry into how systems shape, record, limit, and contain lived experience. By making visible these otherwise obscured organizing frameworks, Cox’s work poses the question: Once art reveals these systems, can agency be found to rethink, reorganize, and reshape them?

Burnaway is excited to continue Burnaway Artist Editions, a short run of art objects created by artists from the South and the Caribbean and intended for a broad scope of discerning collectors.

For our second Artist Edition, Joy Drury Cox has created Watching, Looking, Seeing, a bandana inspired by the design of a neighborhood crime watch sign. Cox reworked the icon of a single eye into a pattern, echoing the ways in which the act of looking itself can become a rigid, rote, and potentially harmful process. At the core of this work, Cox asks viewers to reconsider what and how we watch, look, and see the world.