Franchised horror movies are often set in the South. The frequent interpretation is that the South itself is haunted. However, I argue that many horror films are rooted in the Southern landscape because of the Nation’s lens on the South. A franchise like House of 1000 Corpses (2003) is set in the South not because Southerners are more susceptible to suffering, but because America believes that the torture inflicted on the region occurs in perpetuity.

House of 1000 Corpses is a prime example of Gorecore. The Gorecore genre includes visuals or music with imagery of death, murder, and blood. The aesthetic approach follows Grindhouse films, which contain large amounts of sex and violence. While the quality of Grindhouse varies, most are low-budget films. Many Grindhouse films, much like Gorecore cinema, retain a cult following long after their release dates.

House of 1000 Corpses (2003), directed by Rob Zombie, follows a group of teenagers navigating their way through the Southern landscape only to be trapped and tortured by a demented group of relatives, the Firefly family. Set in a fictional town in Texas, the Firefly’s get their kicks kidnapping young tourists. With playful intercuts of old films, newspaper clippings, and frequent use of split screen, there is a lightness to this gruesome tale of murder and madness.

The trope of youth traveling through the South only to be tortured runs through many franchise films set in the region like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and The Evil Dead (1981). The frequency of this narrative suggests that young people are primarily punished in the Southern landscape. Perhaps it is not because of the assumed promiscuity of this age group, but simply because they begin with more geographical agency. Unlike the South and the depraved villains who call it home, these groups of young individuals are granted flexibility and movement at the beginning of the film. Nevertheless, as the story progresses, Gorecore demands that these adolescents ultimately become trapped like their antagonists. The films suggest it is not as terrifying to be a young person trekking through the South as it is horrifying to be contained in the landscape indefinitely.

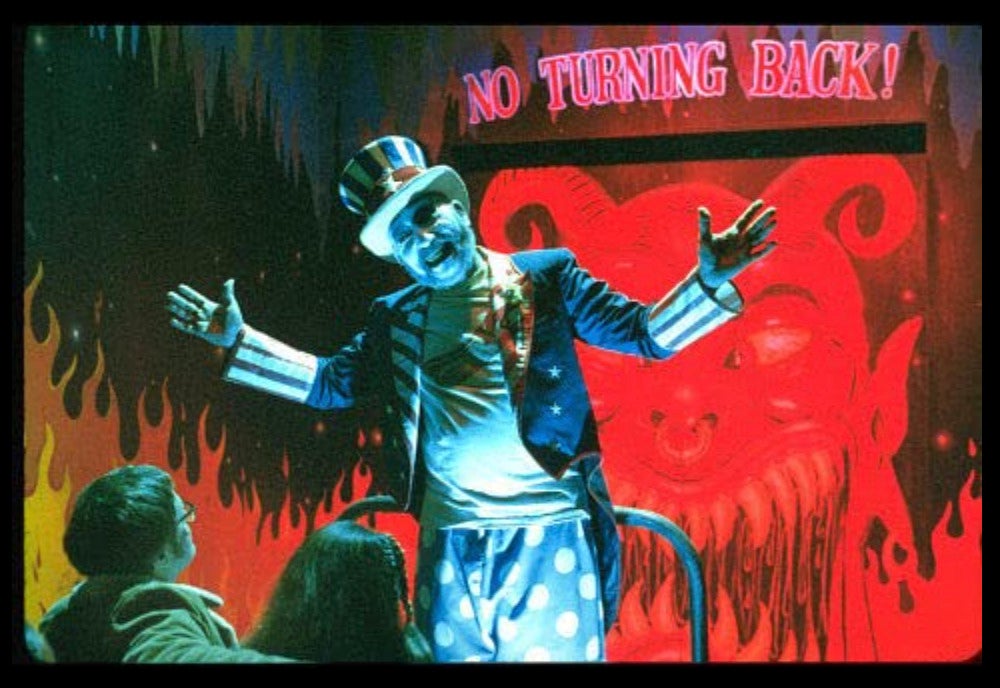

In the beginning of House of 1,000 Corpses, four young men and women visit Captain Spaulding’s Museum of Monsters and Madmen, while conveniently writing about outré attractions on their road trip. During a museum tour, the group learns about Dr. Satan, a mad scientist who experiments on patients with sick pleasure. On a subsequent quest to find where Dr. Satan was allegedly hanged, the group picks up a hitchhiker named Baby, who unknown to the travels, is part of the Firefly family. There is a sexual nature to the House of 1000 Corpses kidnappings, from Baby’s scantily clad appearance to the relationships between the young travelers, and ultimately, to the way the Firefly family manipulates their victims. In the end, no one from the party survives the deranged, rural townies. The Firefly family’s tortured victims were nicknamed “Yankee boys,” which serves as an affirmation that those who enter this mad tourist attraction from outside of the South are particularly doomed. The intensity of the torture and the humor in Zombie’s storytelling makes it an anomaly even among older horror franchises.

The original flick and the Director’s subsequent films, including Devil’s Rejects (2005) and 3 From Hell (2019), perpetuate the feeling that suffering in the South is a never-ending occurrence. For example, even when the originally presumed “final girl,” or “the one character of stature who does live to tell the tale,” is about to escape, all roads lead back to her torture1. The remaining young woman from the original group runs for hours but is abducted once more and mutilated by Dr. Satan. Furthermore, the franchise suggests that the very torture that takes place in the South is so incredibly upside down that whoever dares to pass through or worse, relocate to the seemingly damned area, is asking for whatever hellish experiences they have coming. Like the viewer who arrives to watch an in-your-face grotesque film with “1000 Corpses” in the title, the idea of moving to the South is often drenched with the connotation that existing in the region will be pervaded with backwards experiences, whether it be with locals that are stuck in the past or lawmakers who plan to enforce conservative politics across the region.

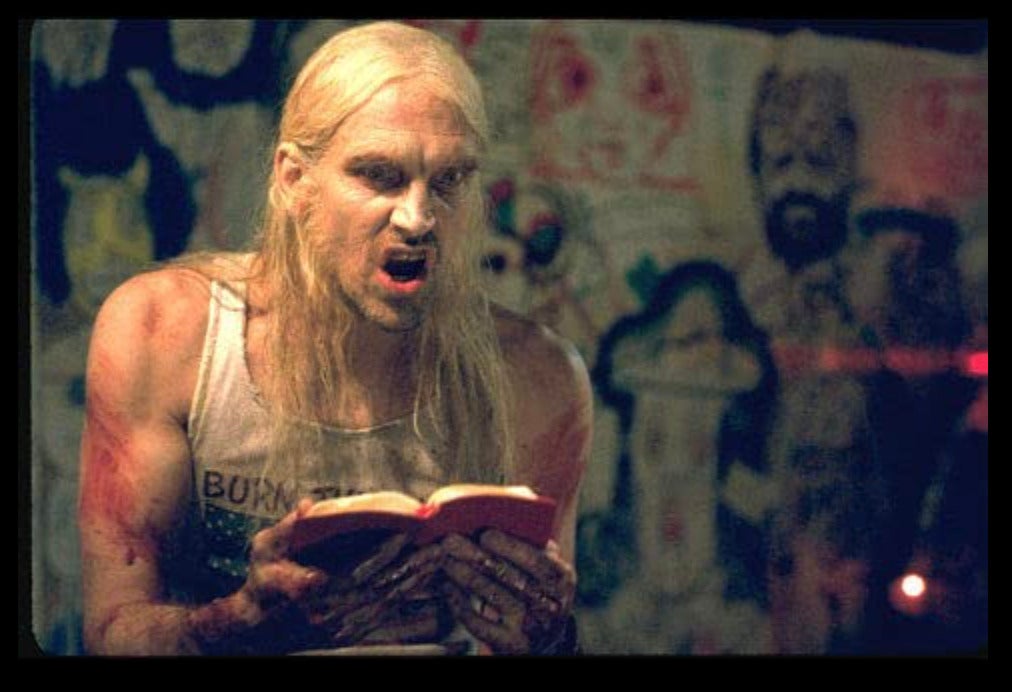

It is uncomfortable to compare local Southerners to the Firefly family, with their comical “Burn This Flag,” anti-American branded apparel and their exuberant vaudeville performances. However, the caricatures forces one to question Southern stereotypes. In the film, the patriotic dedication that permeates a general, national notion of the rural Southerner is turned on its head. Zombie was inspired by film franchises like the Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and The Evil Dead (1981), however, he gives his antagonists depth and humor, while providing a rich history to this fictitious Southern town. The implication is that the only people who can survive living in the South are the fully realized individuals— those who know this landscape (above and below— including the corpses referenced in the title and Dr. Satan who resides underground) like the back of their hand. Zombie’s elimination of the “final girl” from a film that clearly pays homage to past horror franchises set in the region, along with the nuance he ascribes each antagonist (who know the area better than anyone else), asks the question: Who needs a final girl when you know the final destination this damn well?

The film relishes the obvious, from its gritty title to its portending wrong turn plot. The expected storytelling might remind one of the common questions that people who live in the South often receive from Americans outside of the area, like “Isn’t it scary living in the South?”; “Isn’t it backwards there?”; “Don’t people in the South hate [insert marginalized group here]?” The dark playfulness of this franchise, and Gorecore, relieves the tension underpinning these questions. The antagonists of House of 1000 Corpses differ from the disenfranchised murderers and disembodied wickedness much of the genre offers. After decades of working its way up to be viewed as a mad tourist attraction within the cinematic Gorecore canon, the deranged Southerners in this horror film are finally getting the last laugh.

1 Carol Clover, Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 44.