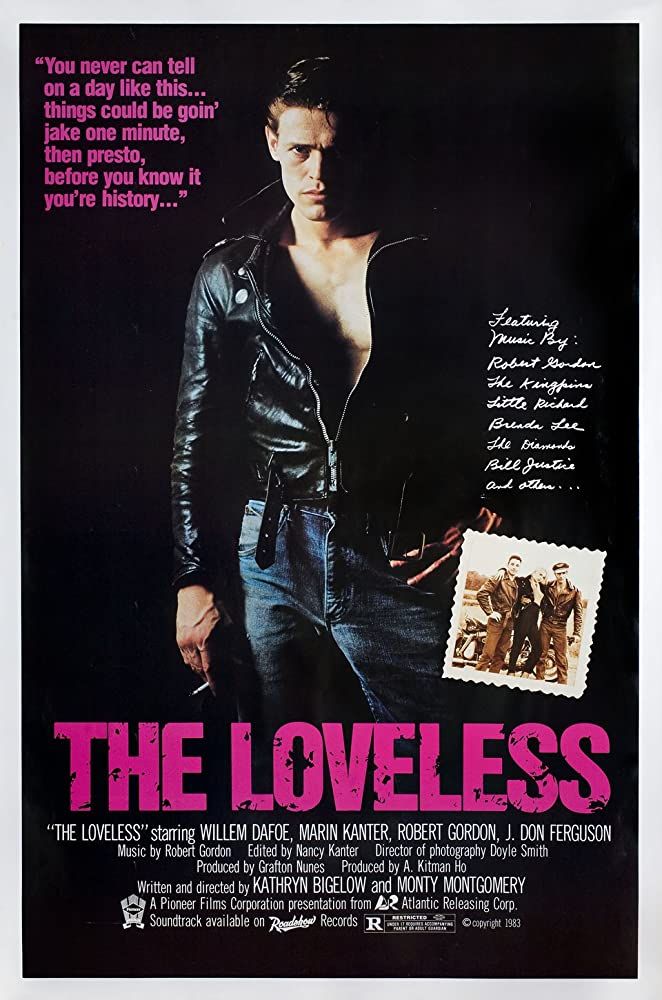

Kathryn Bigelow and Monty Montgomery’s indie film The Loveless (1981) was made at the tail-end of the “1950s remembrance phase” and received a hefty $1 million budget from Atlanta investors who were promised a film made in Georgia with local crew.1 As a project born out of the avant-garde New York art scene, The Loveless avoids many of Hollywood’s clichéd 50s fantasies of poodle skirts and teenage drama, instead imagining the decade as a collage of 50s outlaws, 60s queer subculture, and 70s politics. The film presents a sense of past that is already embedded with its future, and it highlights the aging process through techniques of pastiche.

Hollywood regularly invokes nostalgia as a past-directed affect, often a longing or a sense of loss, aroused by its mise-en-scene. The time-stamped costuming and set design paint a fantasy of the past that rarely aligns with historical accuracy, instead recreating objects of the past that themselves were mythologies of their present. In some ways, The Loveless is born of this nostalgic tendency in that it was inspired by 1953’s The Wild One, starring Marlon Brando as a member of a crude California motorcycle gang. The Loveless mimics basic narrative beats: a New York motorcycle club becomes stranded in a rural Georgia town on its way to Daytona. However, unlike traditional cinema nostalgia, Bigelow and Montgomery’s film recognizes nostalgia aesthetics as a collage of symbols from various eras that find meaning only when superimposed with the present’s view upon the past.

Both trained in New York visual art programs before meeting in Columbia’s graduate film school, Bigelow and Montgomery first collaborated on The Loveless, a project which brought Montgomery back to his Georgia roots. It is not surprising that The Loveless indulges in cultural stand-offs between Northern outsiders and Southern insiders. Montgomery, acting as his own location scout, found a nine-mile piece of US 17 that was bypassed by the newer I-95 in the 1970s, leaving it “in a timewarp” of unrenovated 50s buildings.2 The film paints this unvisited corner of the South as backwards, and in many ways it is authentically lost in time.

The Loveless is filled with tableau-vivants of characters languishing in the heat. The camera slowly pushes in on scenes while the characters laid out across the frame hardly move. This setup evokes photographs more than film, as though the motorcycle crew is trapped by the oppressive heat and their inability to beat it with engine power. This type of shot is the most classically “nostalgic” of the film in that it preserves a moment in time. Yet the film medium denies a complete freeze. Instead, we are given tableau-vivants that still live, breathe, and exist in time, albeit a slowly progressing temporality that resists transition into the future.

A saturated red Coca-Cola machine stands at the corner of an aged garage, sparkling in the hot sun. Set against the green overgrowth of the abandoned lot, the Coca-Cola machine burns hot. Vance leans on it in his full leather outfit, an outsider dressed inappropriately for this weather. When he snaps open a Coke, its refreshing crispness in his hand is visceral, even without a close-up insert.

Enhancing the tableau-vivants’ resistance to progression is the involvement of New York City rockabilly culture into the film’s production. Apart from Willem Dafoe, who Bigelow sourced from an avant-garde theater troupe, the cast of The Loveless are non-actors. The Southern townsfolks were largely played by Georgia locals. And the New Yorker motorcycle club was largely played by New Yorker rockabillies, including hairdressers and Robert Gordon, a famous musician within the scene. In many ways, the rockabillies in the film production guided the 1950s aesthetic frozen in a series of impressions of their own leather, haircuts, and Harleys.

Producer Grafton Nunes refers to the film as “a succession of poses”, which aligns with Bigelow and Montgomery’s interest in photographers of 1950s counterculture.3 In particular, the preproduction lookbook referenced Diane Arbus’s and Robert Frank’s portraiture—specifically Robert Frank’s series on American motorcycle clubs. In these photographs, the bikers are not as cleanly presented as in any cinematic portrait, including The Loveless. They mix denim into their leather; their jackets and bikes are garishly studded; they wear cuffed pants and flannels as they work on their bikes.

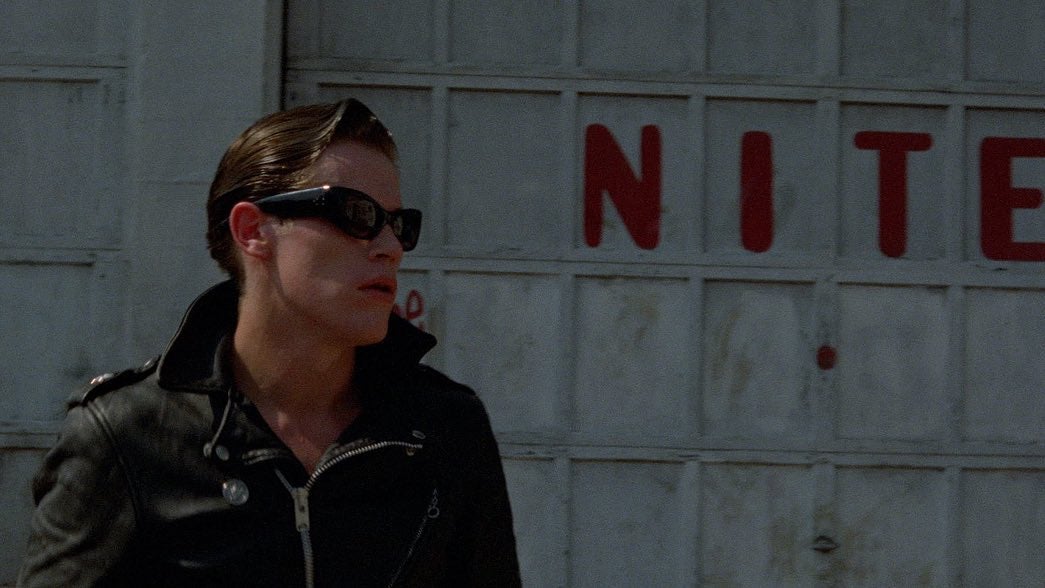

This is a far cry from the all-leather-clad, adornless bikers of The Loveless, which pulls far more from the 1970s/1980s rockabilly aesthetic than from Robert Frank’s portraits. Though openly nostalgic in spirit, the rockabilly aesthetic does not discriminate between 1950s cultures. It picks up the leather jacket from outlaw bikers, but cleans it up in order to distinguish it from the 70s punk scene. Rockabillies also accept letterman jackets, rock n’ roll blazers, and aviator sheepskin coats. This pastiche aesthetic explains why, in The Loveless, the club leader wears a flat top haircut, which aligns more with 1950s veterans, cops, and football heroes than with outlaw bikers wearing pompadour styles like jellyrolls and duckbills. There is no authenticity in bringing these disparate fashion aesthetics together into the same venue or the same frame; yet for rockabillies, and the film, nostalgic remembrance is better seen as a shared attitude towards the past.

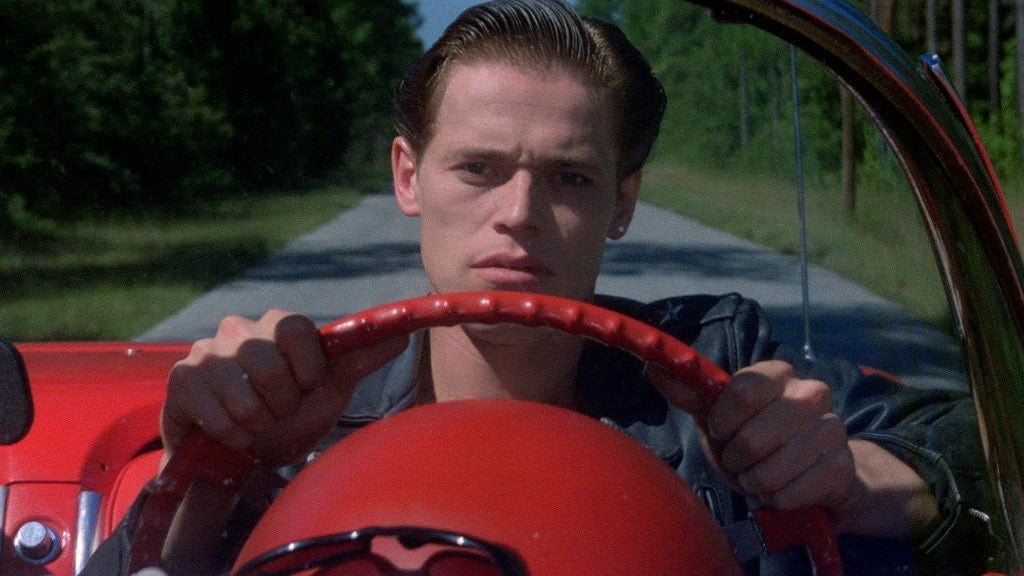

Midday. Vance and Talena drive her roadster to create some wind, relief from the sun. The blacktop of US 17 is rough, like Vance, who makes no attempt to seduce. He is restless and bristles at questions. The cigarette ash dangling from his mouth threatens to fall into his lap when Vance says, suddenly, “I need a beer. Where’s a liquor store?”

The film’s pastiche whereby multiple eras are superimposed is shown further in the film’s political attitude, which mimics 1980s New York Times headlines of racial discrimination, segregation, and injustices ongoing in the South. In one scene, Vance stops at a Black-owned liquor store after Talena, his love interest, explicitly tells him not to, as it is “run by darks”. In fact, at this statement, Vance speeds up to get there faster. He is eager to show off his lack of racism, as he comes from the North. The clerk in the liquor store barely acknowledges Vance’s presence, and he quickly retorts: “I ain’t as White as I look”, aligning himself with what he sees as the “outsider” crowd of the town. He expands on the white townsfolks’ language, as they consistently refer to Vance with the racially coded term “boy”, to which Vance playfully redirects the connotation by calling back: “hey dad”.

Adding to the anachronism, a piece of footage plays on a motel TV showing race riots in a segregated subdivision in Illinois from 1951. Without a newscaster voice-over, the television behaves as an eerie time warp, as though it spontaneously plays vintage footage. The screenplay sets the film’s events in the late-1950s, so this 1951 footage pushes the characters even farther into the past than the costume design. The historical event, enacted by a mob of 4,000 eastern European immigrants in protest of a Black family moving into the area, acts as a counterargument to Vance’s superior and performative Northern attitude to racism. Segregation was socially and culturally upheld in the 1950s North too, the film reminds viewers.

The motorcycle crew works on bikes in the garage. A series of close-ups give us a romantic view onto the texture of their world: a leather wrist-band with metal clips; a nude pin-up tattoo; studded leather seats against shiny red engines; speedometers; jeaned male crotches adorned with oversized belt buckles, chains, and thumbs hooked into belt loops.

In addressing the mythology of past-oriented nostalgia, The Loveless pays homage to the aesthetics of Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963) in these leather scenes of masculinity. Anger’s work itself is a constructed avant-garde view of the American motorcyclist myth. It is a pastiche of pop signifiers: comic strips, James Dean posters, and Marlon Brando films (including The Wild One). It is no wonder that Anger’s work is a peak example in Susan Sontag’s famous 1964 “Notes on ‘Camp’” article, where she argues that temporal distance from an object transforms it from banality to fantasy.4 This view flows into 1960s concepts of Postmodernism in that it juxtaposes new and old artifacts, often finding joyful play with the inversion of the old into new territory. It revels in a collage of images that do not temporally belong next to one another, preferring paradox and the carnivalesque to direct reenactment.5

Yet the film medium denies a complete freeze. Instead, we are given tableau-vivants that still live, breathe, and exist in time, albeit a slowly progressing temporality that resists transition into the future.

By recycling this pastiche strategy, Bigelow and Montgomery aim not only to reference specific images, but to dredge up its same philosophies of time. The Loveless has an affection for the old, not in a singular longing for a bygone era, but in the process of aging itself. It approaches each referenced temporality (50s, 60s, 70s) as attendees of the Carnival, a playful exchange of images, ideas, and attitudes in costume form. For Vance to move back in time as he travels from 80s New York deeper and deeper into the 50s South is not to ask the audience to adopt a longing affect for time lost. Rather, the film asks viewers to appreciate how deterioration plays into past objects in an additive way, bringing modern attitudes that stir the past awake. Considering the past aesthetically is not to see it as it was, but to campify a sense of duration. The Loveless exaggerates the process of aging, making the 1950s past feel farther away, while also presenting visions of the past that lean into their future. It cares little about projecting a snapshot of time lost; rather, the film recognizes nostalgia as a sense of fluid duration, a collage of temporally-directed affects that privileges a multitude of histories over the singular past.

[1] Monty Montgomery, “Commentaries,” The Loveless, Criterion Collection. DVD.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Grafton Nunes, “U.S. 17: Shooting the Loveless,” The Loveless, Criterion Collection. DVD.

[4] Susan Sontag. “Notes on ‘Camp’.” In Against Interpretation and other essays, 275-292. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1964), 285.

[5] The term “carnivalesque” comes from Mikhail Bakhtin’s writing on Rabelais. It references the Carnival tradition of medieval culture that allowed for temporary reversal of power structures where the peasants were encouraged to parody the King and Church through mockery, costume, role-play, and dialogic voices. (Rabelais and His World, 1968)

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Twang.