Hazy images are “arranged and layered,” congealing in whisps of smoke that edge near the pitch of a mountain, and another curve of an orange sun on the upper corner of the print on dibond I know a place where they perform miracles, 2023. I saw this same sun in 2021 when ash rained down on the Pacific Northwest and obscured Mt. Hood, casting a blood orange expanse across an otherwise gray Portland sky. I do not know if one such image of the Pacific Northwest is buried in the blur of composite images. In fact, looking at the larger series “Is this Paradise…” (all 2023), the collaborative duo Ghost of a Dream, comprised of Lauren Was and Adam Eckstrom, anonymize the sources of the images within a collective whole—a whole seemingly devoid of paradise and miracles. They employ an opposite strategy in the multi-channel projection installation aligned by the sun (within the revolution) (2023), detailing hundreds of collaborators in meticulously denoted text panels. This careful revelation of the singular and collective in the exhibition I know a place where they perform miracles on view at MOCA Arlington, January 20–March 17, 2024, confronts the flattening affect of present-day image regimes—too often wielded on whims by suspect sources. The works ultimately delve into a dialectic density of twenty-first century environmental crises.

Whereas the early 2000s and 2010s might have been mired in debates concerning the realities of climate change, Ghost of a Dream’s large-scale photographs in the series “Is this paradise…” encourage viewers to think beyond this loaded terminology and surface knowledge, investigating the layers of its calamity, and, as catalog essayist Julie Reiss notes, “duration” it takes to create these environment crises and also to view them through Ghost of a Dream’s layered strategy. They gradually gathered the images from then-current news, removing them from their original contexts and re-siting them in compounded images. In the context of MOCA Arlington—in which multiple simultaneous local and international artist residencies, exhibitions, and hundreds of community-based programs take place per year—and the liberal suburb of Washington DC, I know a place where they perform miracles seems surprisingly less like a challenge to audiences than an invitation to meditate on human roles and possible action.

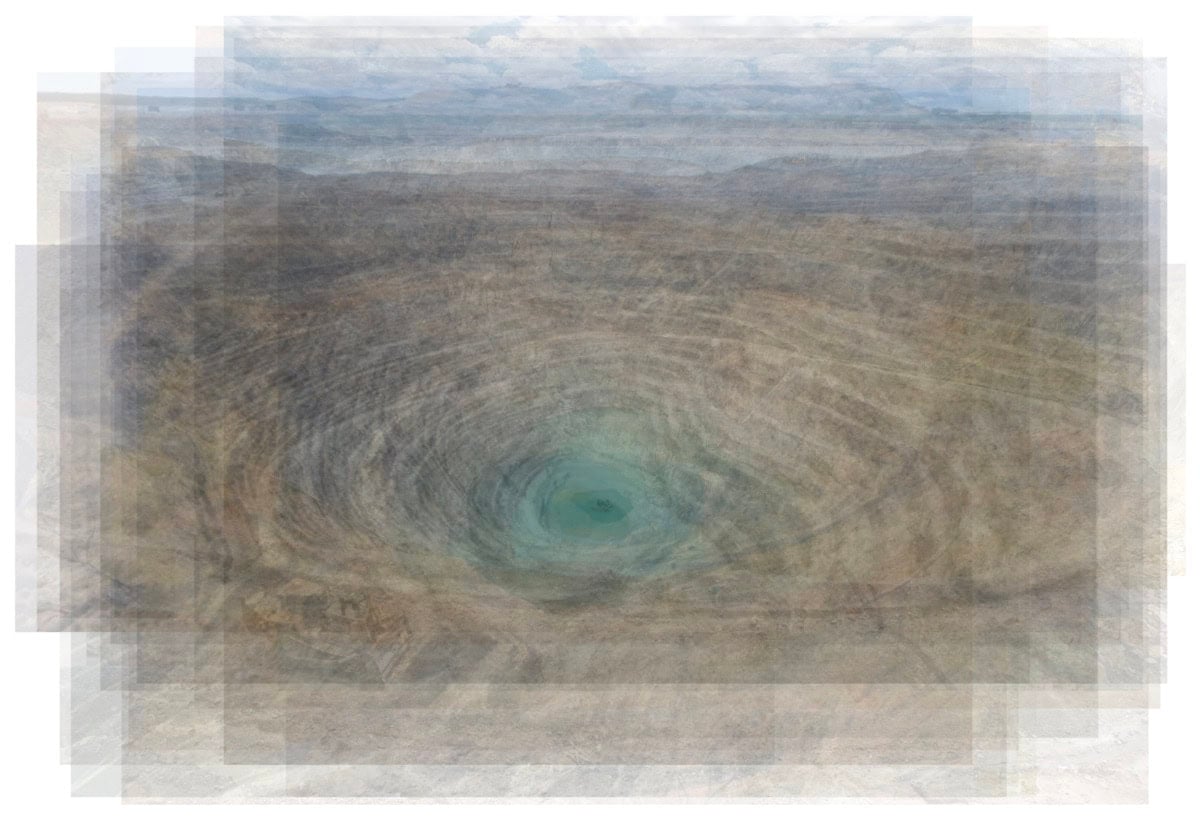

Just yesterday mornin’, they let me know you were gone, drifting icebergs float away from one another as the corners of photographs layered atop one another compress into a readable “portrait” image, as described by the wall text. We can imagine that the individual images, glimpsed in a newspaper or scrolled through on smart phones made us pause, but did they give “the full picture”? Could we ever fully see it, even if right before us? Even with multiple images composited together, the portrait of softly melting ice in the sunlight eludes the harsh reality of actual glacier melt, pointing towards the fickle evidentiary nature of the photograph in twenty-first century circulation. The effect of perpendicular and horizontal lines, belying the photographic image edges in Thunder drowns out what the lightning sees, as opposed to stacking in other images in the series, intervene but stop short of disrupting the circular gauges in the earth as the result of cobalt mining—providing precious raw material for phones and electric cars. The multiplicity of lines becomes an optical rhythm, requiring the added labor of our eyes to register the image. They pose a challenge to casual looking, requiring a certain intentional gaze.

The titles for images of unchecked fire scorching swaths of land such as the work I know a place where they perform miracles, convey a certain pessimism and even banality. They suggest that viewers are familiar with such sights, and even their affective aftermaths. That Ghost of a Dream renders the individual inextricably tied to the collective within the context of art concerning the environment is not new, especially within discourses of the Anthropocene. But the strategies they employ to reveal compounded intricacies of crises are novel. They mirror our intertwined and circulated mediation back to us, acting upon our minds and physical conditions with and without our knowing.

In fact, these works are probably not the crises we expected to see: fire-fighting planes, cobalt and lithium mining, forests blazing, deforestation cutting, or coral dying. These are, as curator of exhibitions Blair Murphy explained, the crises that are relegated to the long-term ongoing markers of environmental collapse—not those that always grab the cover story. The fact that the images are titled with seemingly banal song lyrics, from bands and musicians such as Clap Your Hands Say Yeah, James Taylor, and Prince, gives them a certain dream-like relatability—almost as if we know these underlying crises too well, almost as if we are always already complicit in their happenings.

In the final room of the exhibition, the seven-channel installation aligned by the sun (within the revolution) (2023), spins around the room emanating from projectors above head. It recasts the sun over and again from found footage snippets shot by multiple collaborators across world onto the walls of the lower gallery at MOCA Arlington. The tangerine sun of a sunset melds gradually into the soft yellow of a waking sun, which is reflected on the sun grazing a sea as the projectors continue their revolutions. The sounds of multiple languages drift throughout the space, interspersing calls to prayer, bird chirps, and other ambient sounds from the overlapping footage. As opposed to the anonymized composite images from “Is this Paradise…,” the films are meticulously marked on the wall labels, recognizing collaborators ranging from Dawit L. Petros in Eritrea to Olafur Eliasson in Iceland to Pedro Reyes in Mexico. The contributors provided footage from 193 UN member countries with the prompt to “capture a short video of the sun” in a collective meditation concerning location, migration, and environment, as the artists share on their website. Thankfully, and in spite of their proximity to the governing bureaucracies of Washington D.C., the artists also look beyond nation-state borders, considering collective entities including sovereign Indigenous nations, disputed territories, and non-UN nations. All of them revolve around, cross-cutting and fading in and out of one another, creating an affective relationality.

That Ghost of a Dream renders the individual inextricably tied to the collective within the context of art concerning the environment is not new, especially within discourses of the Anthropocene.

Begun during the pandemic in 2020, the project generated multiple iterations of single-channel and multi-channel video installations available online and exhibited at venues in the U.S. and Ecuador, in addition to stills sold for fundraisers benefitting clean energy organizations such as Little Sun, and installations in public spaces such as Penn Station. At MOCA Arlington, as Murphy mentioned, they wanted to support a new iteration, one that engendered an immense collaborative process. Here, the collaboration across the globe points towards a mutual factor, a commoning sun. Each layer of the found footage illuminates its aerial dominion in the sky. It disregards the bordering logics orchestrated below, and instead radiates above us with sustaining energy and simultaneously daunting regularity. We might think of it as a “place” wherein miracles do not occur, but instead a commoning conviction that tempers any lingering anthropocentric hubris as we watch the earth burn and the sun rise, together.