“We needed an arm of the arts that would be able to bring the word about different issues to people—but not just in political settings, not just in mass meetings, not just in church […] we needed another way.”

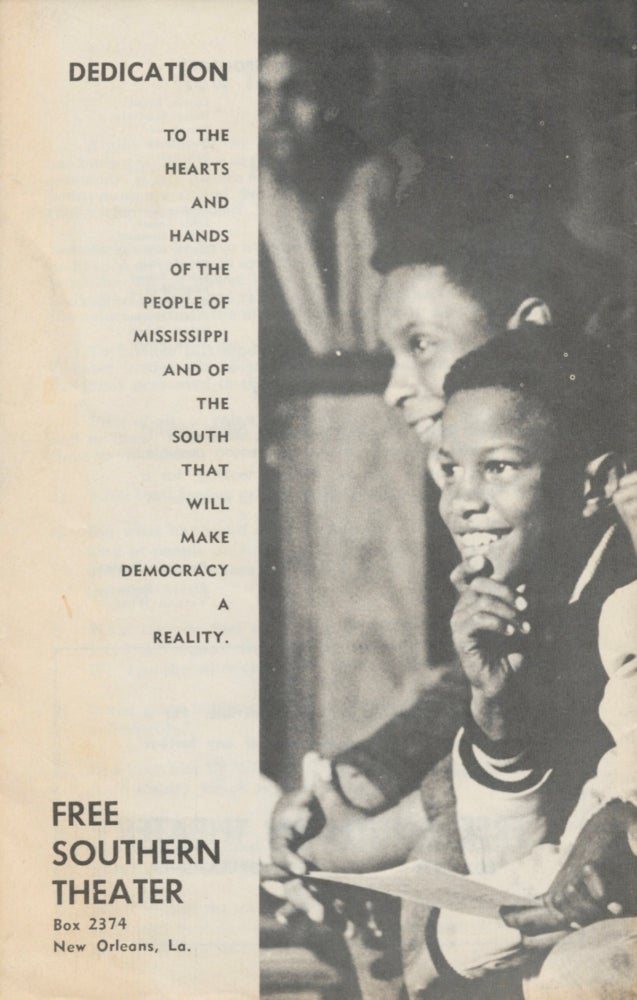

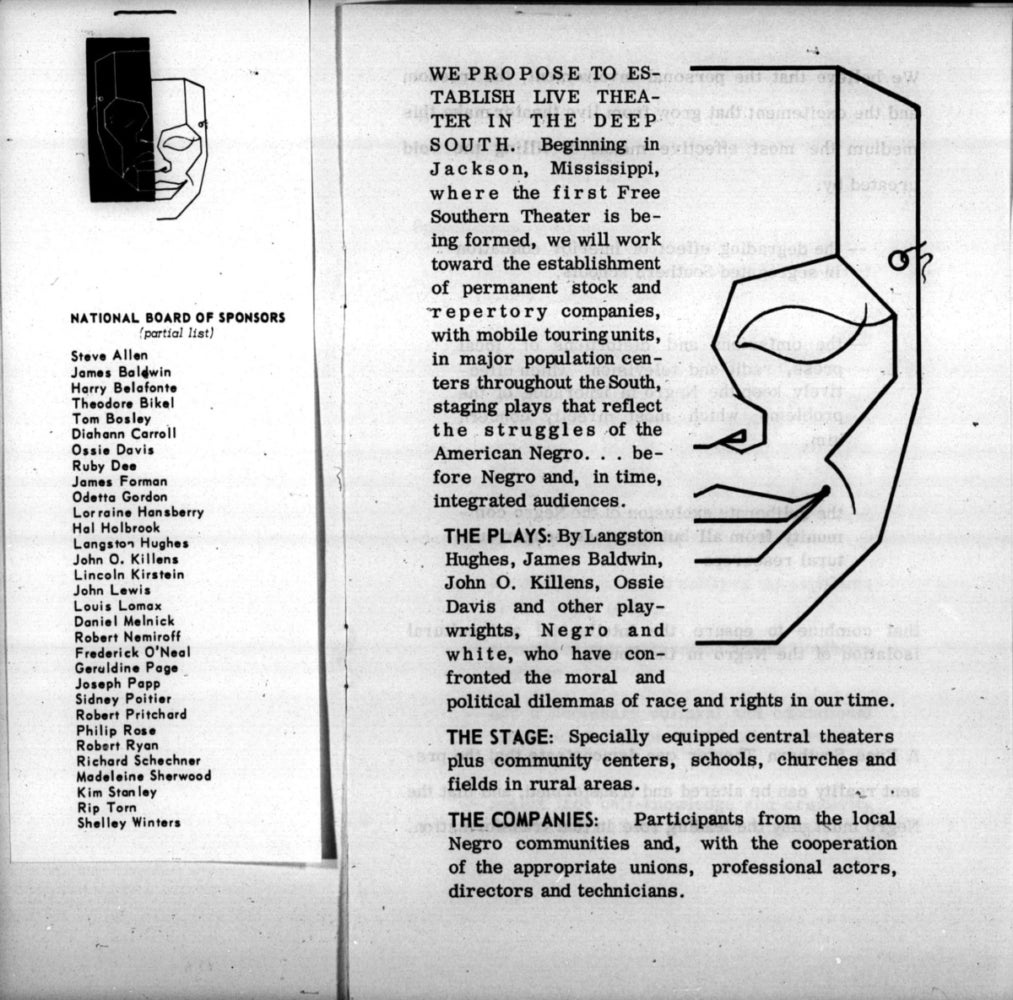

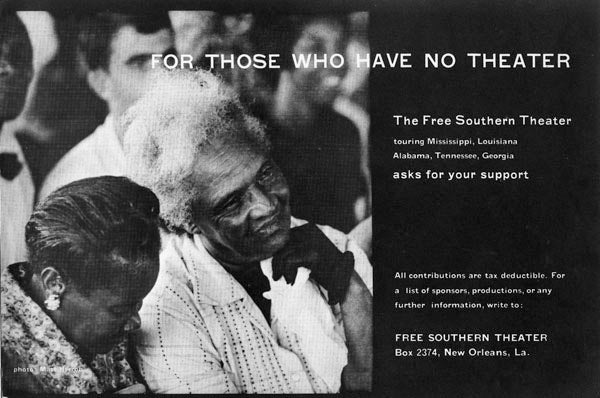

The Free Southern Theater (FST) was founded in Jackson, Mississippi, in early 1964 by Doris Derby, John O’Neal, and Gilbert Moses following conversations between the three of them about the need for a cultural arm of the civil rights movement in the rural South. “We propose to establish a legitimate theater in the Deep South,” they wrote in a document headed A General Prospectus for the Establishment of the Free Southern Theater. “[We] will work toward the establishment of permanent stock and repertory companies, with mobile touring units, in major population centers throughout the South, staging plays that reflect the struggles of the American Negro.” In another founding document, they elaborated further: “We theorize that within the Southern situation a theatrical form and style can be developed that is as unique to the Negro people as the origin of blues and jazz. A combination of art and social awareness can evolve into plays written for a Negro audience, which relate to the problems within the Negro himself, and within the Negro community.”

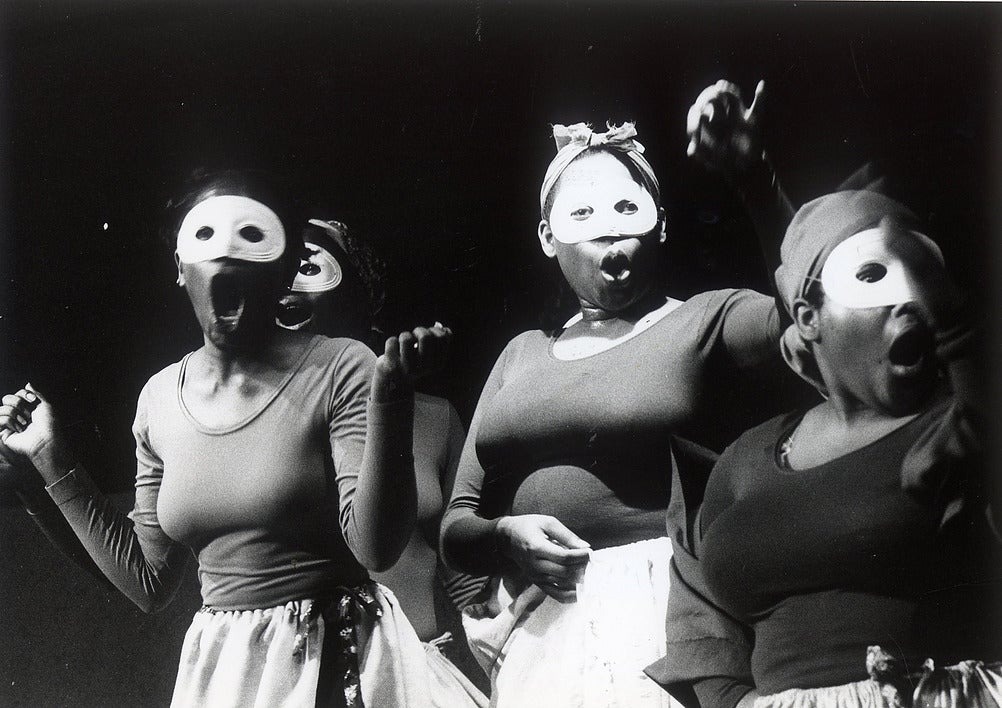

As part of the group’s first tour in 1964, a racially integrated cast performed Martin Duberman’s play In White America for free in towns across rural Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana, as well as in cities including New Orleans, Memphis, and Atlanta. “The people [in Holmes County, Mississippi] came in from the farms to see us. We had to play in the afternoon because they wanted to get back home by dark,” Gilbert Moses later recalled. When members of the Ku Klux Klan killed CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) field workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman in Philadelphia in June 1964, the company revised Duberman’s play to depict the murders. During a later tour, a mostly Black cast performed Waiting for Godot in whiteface in small towns across Louisiana and Mississippi.

In the summer of 1964, following correspondence with Tulane University theater professor Richard Schechner, O’Neal and Moses moved the troupe to New Orleans, where they assembled a board of directors—which included civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer—and occupied office space. Derby, committed to civil rights advocacy and her involvement with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, chose to remain in Mississippi until 1972, later earning a PhD in social anthropology and working for over two decades as a professor and administrator at Georgia State University in Atlanta.

In a conversation printed the Summer 1965 issue of The Tulane Drama Review, where Schechner was an editor, John O’Neal shared his assessment of differences between mainstream contemporary theater and the FST:

“A bunch of fallacies operate in present-day thinking about theater. People think that meaning comes from somewhere out there, pre-established, predetermined. I don’t think that’s so. Meaning comes from involvement, you create the truth of your situation… Theater has taken the tone of the rest of our lives: meaninglessness, otherness, outsideness… Gil [Moses] calls it the ‘ice-cream parlor theater’—a place you go to not even for dessert, just to do something. But the FST has to be bread—a bakery which makes something vitally needed… [Meaning] doesn’t come from oracles; you forge it on the anvil of your own experience with each other.”

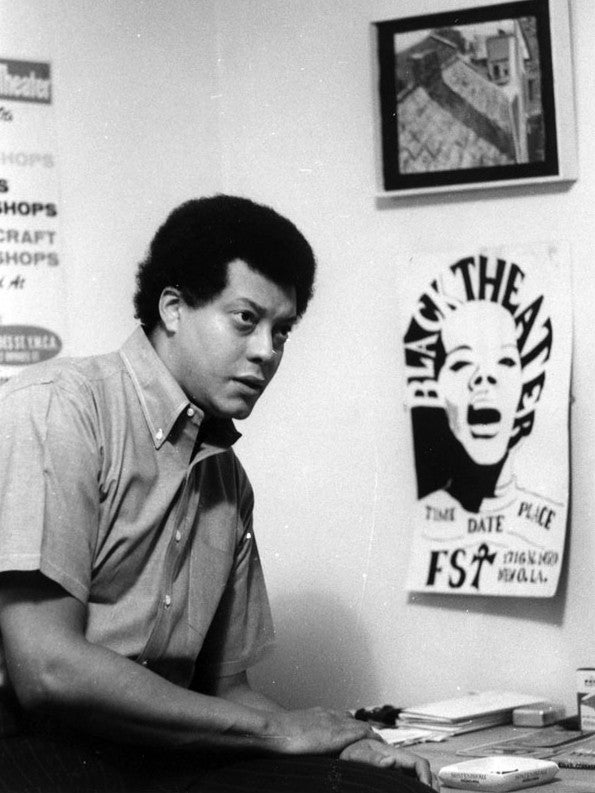

Despite the intentions of O’Neal and Moses, funding ran dry shortly after the FST relocated to New Orleans. In 1966, Moses departed to pursue his interests in music, and O’Neal was sentenced to community service in New York after refusing induction into the military, leaving the FST and its artistic director, Tom Dent, “with little more than an empty building.” Dent was a New Orleans native who had returned to the city in 1964 after studying at Morehouse and Syracuse University and serving as a key participant in Umbra, a collective of Black poets and writers based on New York’s Lower East Side. Under Dent’s direction during the late 60s, the FST’s acting and writing workshops in New Orleans led to the development of groups of poets including BLKARTSOUTH and the Blk Mind Jockeys, as well as Nkombo magazine, which published nine issues from 1968 through 1974. The second issue of Nkombo, published in 1969, featured Song of Survival, a play Dent co-authored with Kalamu ya Salaam about Black Power in the Deep South. Over this period, the FST transitioned from operating as a racially integrated company to consisting exclusively of Black members, often performing original poetry or dramatic works developed within the acting and writing workshops, including Dent’s one-act play Ritual Murder.

In 1980, the Free Southern Theater staged its final performance, a one-person play written and performed by John O’Neal called Don’t Start Me to Talking or I’ll Tell Everything I Know. The play features Junebug Jabbo Jones, a character O’Neal said was “created to represent the wit and wisdom of common folk” in the rural South. While marking the official end of the FST, the performance led to the creation of O’Neal’s theater company Junebug Productions, which is widely seen as continuing the group’s legacy. In 1985, in true New Orleans fashion, O’Neal mounted A Funeral for the Free Southern Theater: A Valediction Without Mourning, honoring the company’s legacy through a three-day conference and jazz funeral.

In an essay titled “Beyond Rhetoric: Toward a Black Southern Theater,” first published in Black World in 1971 and later reprinted in New Orleans Griot, a 2018 collection of his works, Tom Dent wrote:

“I remember Richard Schechner once suggesting that we adapt a Brecht play [for the FST] to fit the southern Black situation… So I set out to adapt this play, I forget the name of it… I was trying to make the merchant a white oyster-boat captain in St. Bernard Parish, and the serf a Black oyster-boat worker, and every time I tried it, it came up more unreal; it was ridiculous. What became obvious as we went through those changes was that we couldn’t just change the insides of the white-oriented material to make it Black, we had to invent something entirely new, our whole concept of Theater had to change.”

Dr. Doris Derby

I’m originally from New York, and I’ve always been involved in the arts and supported theater. I was not an actress, but I really enjoyed theater because of its power. It had the power to reach people and to carry a message and to be an expressive event for people to say what was on their minds and in their hearts.

I became involved in civil rights as an undergrad at Hunter College. I was a Freedom Rider—but not one of the ones who went to Alabama and Mississippi. I went with an integrated group to North Carolina in 1961 to talk with the students who were forming SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee). I graduated from college the following year, in January 1962. I had a friend who decided to work with SNCC in Albany, Georgia. That summer, I was going to be traveling across the country, and I decided to stop in Albany to visit this friend of mine. I ended up staying there the whole summer instead of continuing my travels, working with the civil rights movement.

The movement folks kept asking me, “Well, could you do this? Could you do that? You’re the only one who can do this or that work in the office,” and so forth. They asked me to organize a fundraiser for the movement in Albany, and a young SNCC activist named Robert Moses came as the keynote speaker. While he was there, he tried to recruit me to come to work in Mississippi with him. He had learned that I was a teacher and that I had already worked with SNCC in Georgia. I told him, at that time, that I was going to teach for a few more years and prepare to go to grad school. (My field is anthropology and African American studies—well, African and African American studies.) So I told him, you know, not this time. But he kept calling me and telling me he wanted me to come to work in Mississippi in an “innovative adult literacy project” for Black adults. He wanted me to come down and help him establish a SNCC office and recruit people to be part of this program. This is happening in the spring of 1963, and, of course, the March on Washington is set to occur that August.

I worked in my evening time and on weekends as a volunteer for SNCC, and we were preparing logistics for the March on Washington. So I told Bob Moses that, after the march, I would finally leave for Mississippi. I was the first person recruited to develop this literacy project, which was a spinoff from SNCC.

So a few days after the March on Washington, I left for Mississippi. I was hired as a field secretary for SNCC and began laying the groundwork for establishing the adult literacy office, which was to be based at Tougaloo College, a small Christian college outside of Jackson. I was put up with a family and began my work out of the COFO office, which was Council of Federated Organizations. That’s the acronym: C-O-F-O. It’s a name you’ll hear from time to time. Everybody knew about the COFO office, which was located down the street from Jackson State College, located on Lynch Street, which was named after a Black congressman. So I was working in voter registration as well as starting to see how I could recruit some other workers for the literacy project, including illustrators and other people who were going to work on developing the literacy materials. Eventually, three or four of us became part of the literacy project. By October, I was moving out to Tougaloo, where I had been able to locate a house for myself and two other women who were going to work for the project.

We started in September 1963, and John O’Neal was one of the members of the project. Gilbert Moses was working as a reporter at The Mississippi Free Press. As they got to know each other, John and Gilbert decided to get an apartment together in Jackson. As we worked together in the literacy project, John and I started talking about the need for a cultural arm of SNCC. Everything was segregated and resources were small, and there was a lot of intimidation and violence happening all around the state. But you also had people who were creative, being positive, and trying to create ways for us to get a handle on this inequality, injustice, and violence throughout the city, the state, and other Southern states. We needed an arm of the arts that would be able to bring the word about different issues to people—but not just in political settings, not just in mass meetings, not just in church for those churches who would do that, but we needed another way.

One day I went with John to talk with the two of them at their apartment about starting a repertory theater so that we could take plays out to people. John O’Neal talks vividly about this in one of the video interviews: he says that he and Gilbert were smoking. He’s tapping his foot nervously, getting excited. They loved to talk, to debate. They could have gone on for hours. Me, I was like, “Okay, look, let’s cut through this. If theater means anything anywhere, it should certainly mean something here. Why don’t we start a Free Southern Theater?”

As told to Logan Lockner

Kalamu ya Salaam

When I mustered out of the army in the summer of 1968, I returned to New Orleans and my girlfriend at the time recommended that I check out the Free Southern Theater. Their building was at Louisa and Laussat in the Upper Ninth Ward, just up the street from the canal. When I went to join, they did not have a touring company at that time, but they were still doing the writing and the drama workshops even though performances weren’t happening. Tom Dent was leading us through the writing workshop, and I think we met on Tuesday. Was it Tuesday nights? I think Tuesday—I don’t remember. And the drama workshop led by Bob Costley would meet on another night. But I was a writer. Even though I did acting and script writing and poetry performance, I was more interested in writing. Tom was not an actor at all. Tom impressed me with his personality, and we became very good friends all the way up to his death.

One thing to keep in mind is that the Free Southern Theater basically had three incarnations: the first incarnation was the performance group that went around Mississippi; the second incarnation, one of the famous things they did was a production of Slave Ship by Amiri Baraka; and the third incarnation was John O’Neal’s development of Junebug Productions, which does what we might call performance art.

When you look at musical theater and musical performances, the Western concept is that you perform something based on what is written. What we were doing with BLKARTSOUTH was not necessarily concerned with what was written, and we certainly weren’t tied to doing long plays. How you did it was the issue—whether there was an element of improvisation, much as in music—so that sometimes it didn’t even matter what the composition was that you were performing. It was the way that you did it that made it your thing. There was no one set way to do things. That’s when the aesthetic became clear to me: there was no authority of the script you had to follow; rather, it was what you brought to it, and your interpretation of whatever it was. This was completely new to people who were trained formally to do theater.

The thing that makes it different from traditional theater or traditional poetry is that, politically, it was grounded in an anti-colonization and decolonization movement. We didn’t want to be what the theater establishment said we had to be. We had other ideas. We were in conflict with the establishment, whether we knew it or not. That extended in two ways: one, in terms of the aesthetics of how we went about doing whatever we did, and, two, in terms of content. In both ways, we went against the establishment. The so-called classics didn’t mean anything to us, because they represented the cultural foundations of the academy and the establishment. And that was not our thing.

As told to Kristina Kay Robinson

Sources

Gilbert Moses, John O’Neal, Denise Nicholas, Murray Levy, Richard Schechner, “Dialogue: The Free Southern Theater,” The Tulane Drama Review, Vol. 9, No. 4, (Summer 1965).

Tom Dent, New Orleans Griot: The Tom Dent Reader, edited by Kalamu ya Salaam. University of New Orleans Press, 2018.

Special thanks to the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana; the John Hope Franklin Research Center for African and African American Culture and History at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina; and the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, for access to archival materials related to the Free Southern Theater.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s 2020 yearlong series on Exurbs and the Rural.

This essay was originally published in Burnaway’s 2020 print annual, Laws of Salvage.