In 2014, the state appointed emergency manager of Flint, Michigan, Ed Kurtz, decided to draw water from the Flint River while the city switched its water source from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to the more affordable—but, at the time, still under construction—Karegnondi Water Authority. During the transition, Flint residents complained of rancid water and experiencing nausea, diarrhea, headaches, and hair loss. Children tested positive for elevated levels of lead, and the city suffered a Legionnaires outbreak that, according to the state of Michigan, killed twelve people, sickened at least ninety, and may have killed dozens more whose deaths have been officially attributed to pneumonia. In 2015, the city capitulated and switched back to the Detroit water system, but irreversible damage had been done. Toxic water from the Flint River had corroded the city’s lead-lined pipes, and Flint’s water system was unusable.

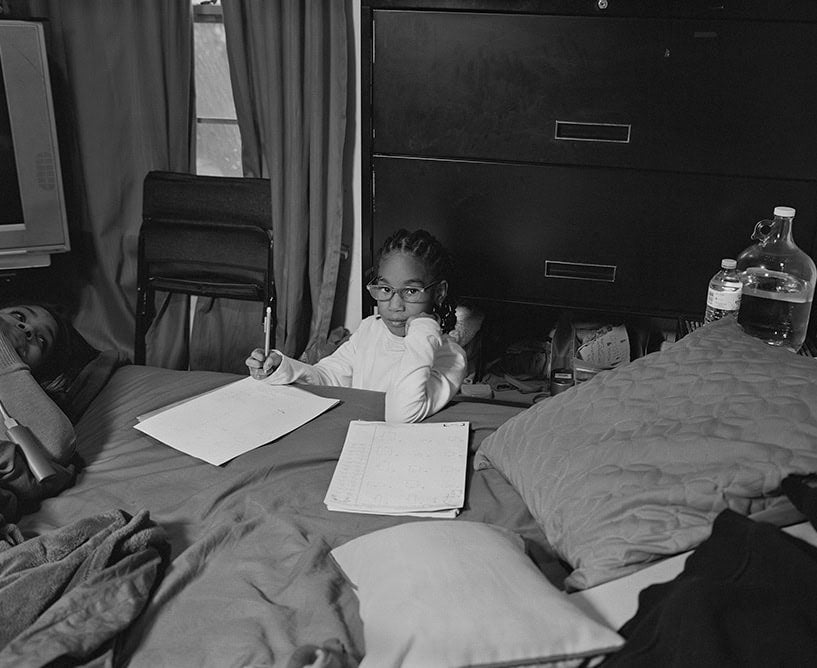

Photographer Ruby LaToya Frazier traveled to Flint in 2016 on commission from Elle magazine. The resulting photographs tell the story of Shea Cobb, a third-generation Flint resident, daughter, mother, poet, musician, activist, and bus driver. These images are on view in the exhibition Flint is Family at Tulane’s Newcomb Art Museum in New Orleans through December 14. In one photo, Frazier shows Shea and her daughter Zion enjoying a meal at a restaurant outside the city limits. They appear happy, but the subtext is that they have no other option but to eat there. They can’t cook with the water in their pipes, and they can’t buy food cooked inside the city limits. In another subtly revealing image, Frazier captures Zion doing her homework, calmly staring at the camera, a jug of store-bought water in the background.

A series of photos shows the women of the Cobb family attending the wedding of Shea’s cousin Nefertiti. In these photos, the couple smiles at each other while reciting their vows. Guests take pictures with their phones. The newlyweds leave the banquet hall with their arms around each other, three children at their sides. But, according to the wall text, the judge who administered the vows was the same one who presided over the preliminary hearing that authorized Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette to charge six state employees for their parts in covering up elevated levels of lead in Flint drinking water.

Another series of photos depicts the flurry of activity surrounding President Barack Obama’s arrival in Flint in March 2016. Frazier photographed protesters, many of them children, waiting for the president outside of North Western High School. He ultimately did not speak to them. In one photograph, Shea’s Aunt Denise and Uncle Rodney are in the foreground, their backs turned to the camera as they watch Obama on television as he raises a glass of Flint water to his lips. The wall text describes Denise and Rodney’s lives in Flint. Denise is an artist and singer, and Rodney, an inventor and professor. Frazier’s message is clear. The national attention is on Obama and the crisis symbolized by the glass that he holds to his lips, but the real story is in the foreground, with the people of Flint: Denise making decorations for Nefertiti’s wedding, Rodney teaching his granddaughter about science.

In a talk at Newcomb, Frazier referenced Gordon Park’s 1968 Life magazine photo-essay “A Harlem Family.” Spending a month with them while working on the project, Parks became a friend and confidant to the Fontenelles, occasionally buying food for their eight children and train tickets for them to visit their son in the state penitentiary. After the essay was published, Parks helped Life purchase a house for the Fontenelles on Long Island with money sent in by the magazine’ssubscribers. He stayed in touch with family members for the rest of their lives.

Frazier seems similarly unable to hold herself apart from her subjects, but where Parks photographed the Fontenelles in some of their lowest moments—one photo shows Richard Fontenelle eating plaster to ward off hunger—Frazier is not interested in depicting suffering in Flint is Family. The closest she gets is a photo that shows Zion brushing her teeth with bottled water. Like Parks, however, Frazier is interested in being more than just a witness, donating some proceeds from print sales to Shea Cobb’s artist collective, The Sister Tour, and funding the installation of an Atmospheric Water Generator in Flint. In her collection of essays On Photography, Susan Sontag writes, “Photographing is essentially an act of non-intervention… The person who intervenes cannot record; the person who is recording cannot intervene.” Is LaToya Ruby Frazier a photographer? By this definition, no.

The common thread linking Frazier’s work has its origins in Braddock, Pennsylvania, where she grew up in the shadow of the Edgar Thompson Steel Mill, breathing air that ranks twelfth in the nation for particulate matter air pollution. Much of Frazier’s early work focuses on Braddock, examining her own pollution-related health problems, the city’s economic decline, the evacuation of schools, hospitals, and social services. More recently, a Levi’s advertising campaign photographed by Ryan McGinley rebranded Braddock as an “urban frontier” where hipster kids wear Levi’s, get blue-collar jobs, and play music and skateboard in defunct factories recast as ruin porn. The majority of the population that remains in Braddock is Black, which brings up a hard truth that Louisianans know well: communities of color suffer the detrimental effects of pollution, climate change, and bad environmental conditions far more than white communities.

During the 1980s in the Upper Ninth Ward of New Orleans, the city decided to build a neighborhood of inexpensive single family homes using HUD money, marketing these homes as opportunities for Black families to rise into the middle class. Almost immediately after moving in, residents of Gordon Plaza began to notice trash including glass and toxic waste surfacing in their yards. They eventually learned that their homes had been built on top of a site that served as a landfill for over fifty years. After 140 toxic contaminants were discovered in the soil and water in 1994, the EPA temporarily designated Gordon Plaza a Superfund site, removing roughly ten percent of the contaminated soil—two feet out of twenty—before revoking the designation. In 2005, the waters of Hurricane Katrina brought additional toxins to the surface.

The American Dream Denied: The New Orleans Residents of Gordon Plaza Seek Relocation is a collaboration between the Newcomb Art Museum and Tulane’s Critical Visualization and Media Lab, a group of graduate students who recorded interviews with residents of New Orleans’s Gordon Plaza neighborhood. The exhibition is not exactly a companion show to Flint is Family. Physically, because of its position in the gallery, it both opens and closes a viewer’s visit, encircling LaToya Ruby Frazier’s photographs, drawing connections between people suffering from environmental racism in Flint and in New Orleans. The American Dream Denied contains more than artworks: there are documents—letters written to public officials, communication with the EPA, newspaper clippings, scientific reports—and videos of Gordon Plaza residents speaking to Tulane students, the kind of proof that LaToya Ruby Frazier denies viewers in her photographs of Flint. One man says his wife died of cancer because she loved working in her garden. One woman says her mother gave up on having more children after having eight miscarriages. One man won’t use the exterior spaces of his house—won’t let his dog in his yard, won’t wash his car in the driveway. One woman describes watching workers from the New Orleans Sewerage and Water Board fixing a pipe clad in white hazard suits. Residents cannot use their tap water. Many are sick, and many have died. Gordon Plaza has the second highest consistent cancer rate of any location in Louisiana, higher than many sites on Cancer Alley. This is the violence wrought on these people’s lives, their homes, and their hopes for equity and the American Dream by a series of five New Orleans mayors who refuse to fully fund their relocation.

The artworks that are included alongside these documents and video footage were carefully sourced from New Orleans artists who are active in the movement to fund relocation. Hannah Chalew, an artist whose work often reckons with the environment, contributed a drawing of Gordon Plaza showing three houses and mountains of trash as if through the distorted perspective of a fish-eye lens. Chalew created the paper from shredded plastic and bagasse, a byproduct of sugarcane production and material reference to Louisiana’s history of sugarcane production, harvested and processed by enslaved people.

Altar to the Ancestors is a work constructed by the residents. At first glance, it appears as a series of mason jars filled with soil. Each mason jar is labeled with the name of a Gordon Plaza resident who died from exposure to the toxic soil that now fills these jars. Viewed in this light, Altar to the Ancestors is a portable graveyard, a reliquary for neighborhood saints. In this work, the residents of Gordon Plaza are subject and object, artist and advocate. They refuse to stay in front of the camera, letting Tulane students ask them questions. In this, they are not unlike Frazier, who is not content to stay in her designated role, who must intervene—and, by Sontag’s definition—become something more than a photographer, ultimately changing the lives of the people she’s documenting. In one of the poems printed in the brochure accompanying the exhibition, Gordon Plaza resident Shera Phillips reimagines the familiar lines of the Serenity Prayer, claiming the moment for action: “I’m asking God for the courage to change / the things I cannot accept. / How many tears have been cried / No more tears, we must fight.”

LaToya Ruby Frazier: Flint is Family and The American Dream Denied: The New Orleans Residents of Gordon Plaza Seek Relocation are on view at Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University in New Orleans until December 14.