“Since leaving was never voluntary, return was, and still may be, an intention, however deeply buried.”

– Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return (2001)

Invoking feelings of yearning, compassion, and tenderness, Trinidadian artist Rodell Warner’s Fictions More Precious, curated by Coka Treviño, at Big Medium in Austin, TX, also brings up spirits, specters, and wonder. Part of his work presented as the 2023 Tito’s Prize recipient, the exhibition builds on Warner’s digital excavations, experimentations, and conjurations around the problematics of the colonial archive in the Caribbean. With apparitions floating in mid-air, and conceptualized ghosts in the proverbial AI machine—this offering of images of ancestors passed and imagined at Big Medium feels apt in title, location, and intention.

The site, a former warehouse in an industrial area—a setting of surplus, with images of laborers—becomes a virtual seance of sorts, aided in part by Warner’s audio. Heady meditative reverberations of the artist’s making resound throughout the space, grounding the body more fully in the viewing experience and adding to the sense of encounter with the images. Wires are exposed on projectors, and the warm aura of innocuous, domestic lamps illuminate aluminum photographic prints for observation. There is a sincerity and gentle poeticism in the intentional curatorial choice of having the proverbial guts and mechanisms of artistic display made visible. It signals a vulnerability and openness, and it feels unpretentious, fallible, and most importantly, curious. This is an exhibition categorically in one sense, yes, but for those willing to enter and perhaps imagine their own loving fictions as viewers, it is also a communal altar to the varied, full lives of ancestors that will largely remain untold and uncelebrated due to the historic intentional erasure of documents from archives from the Region [1].

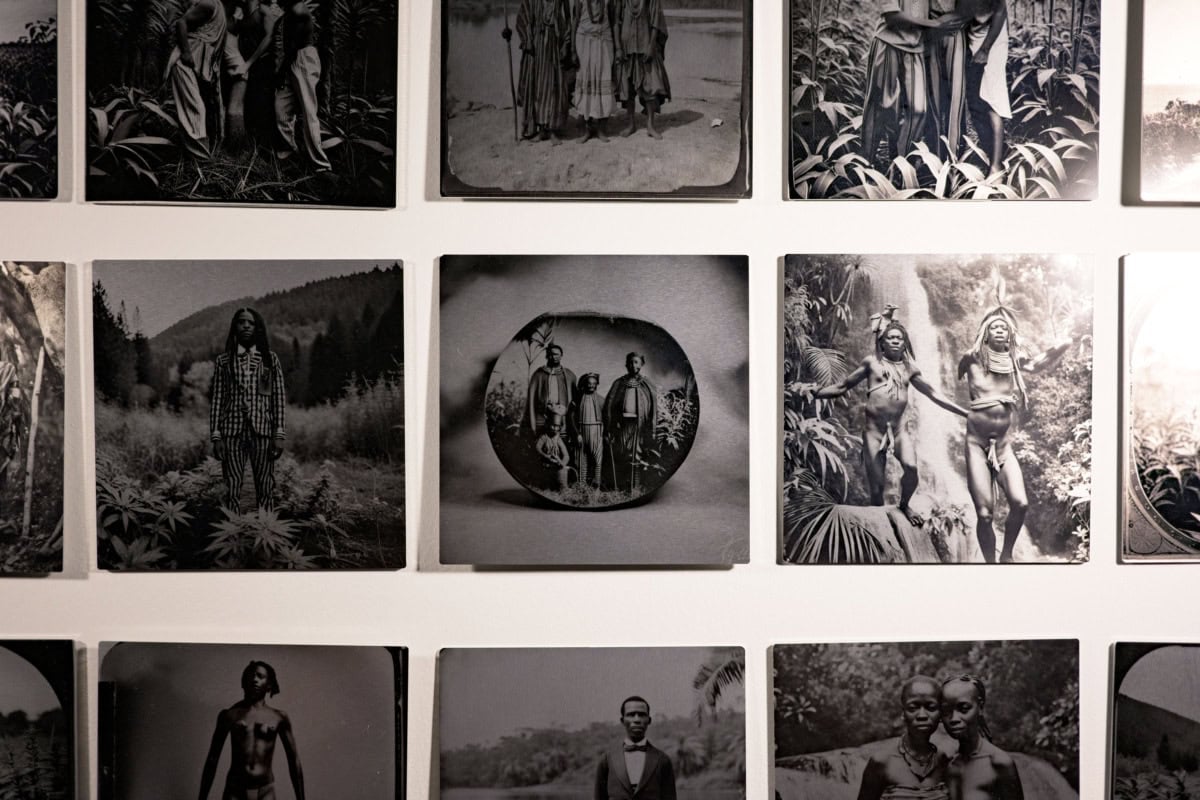

There are two primary bodies of work that Warner has drawn on for the show at Big Medium. Beginning with pieces from his Augmented Archive series, we see this body of lovingly recolored images from the archive with his characteristic digital spectral objects as interventions in-frame. Displayed both on Infinite Objects as well as projected large on the walls of this warehouse-turned-laboratory of caring and fervent fictions, the pulsating specters disrupt the implied passivity and oppression of those pictured, re-activating the images and turning them from colonial documents into moments of encounter with the supernatural or divine.

Similarly, works in the Artificial Archive work to humanize the narrative around Caribbean people outside of labor, but through a different methodology entirely. Using AI to generate images of Caribbean people at rest, in leisure, when this has historically been deficient within the archive, we are presented with faces that by all means do not exist. They are not real people, but they are faces which, for those who have their heart tied to the Region, appear so uncannily familiar that the heart aches for it to be truth and to see these joyful lives actualized.

Tender recolorizations and thoughtful AI prompts (and conceptual probing on Warner’s part) have helped lead to a body of work that shows the care and warmth so often missing in both the colonial photographic archive as well as some preconceptions of work in the digital realm as ubiquitous, cold, and cheap as the means of production. Where is the beauty in the everyday lives of the locals pictured in the colonial archive? Why are scenes of joy, intimacy, and leisure missing from the images of Black, Indigenous, and queer people of color especially? What is missing can at times have as much presence as what is physically present, and Warner’s mix of digitally tended-to and artificially generated images generously gives us both. Warner’s intervention with these spiritual objects wrests power away from the hegemony of the colonial gaze, the tension of viewer and viewed, and instead invites us into the frame as a portal, showing Caribbean people encountering the fantastical in the midst of the mundane, offering escape and hope in a retroactive way.

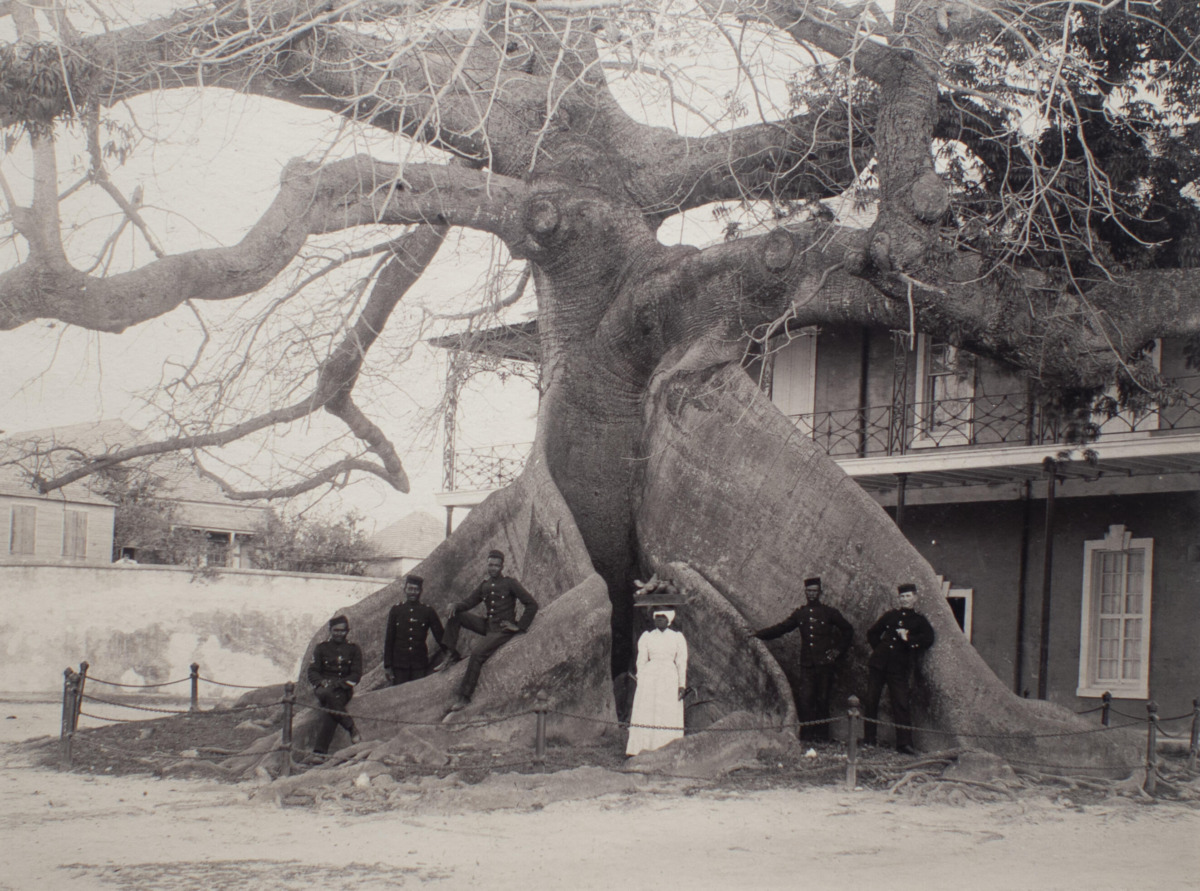

The historical archive in the Caribbean context can be seen as a site of tension, exploitation, and colonial power—having less to do with the ideas of truth or integrity in the way that might ordinarily be associated with these historical objects and images. Coming from a place where the definitive narrative of your Region [2]—one of luxury, respite, and exoticism—was constructed by colonial tongues with empire’s interests in mind, images from these particular days gone by don’t tend to spark feelings of fond nostalgia nor offer much palpable sense of historical grounding for national identity. In this way, colonial photography of the Caribbean region is perhaps best taken as propaganda of the empire, rather than an accurate or objective record of what had been—something that Warner, as an interdisciplinary artist from the Caribbean dealing primarily in photography and digital work for the majority of his career, is aware of.

Left: Colonial archival albumen print, Untitled (Silk Cotton Tree) (ca. 1877-78) by Jacob Frank Coonley, from the National Collection of The Bahamas. Images like these were used to show the lushness and abundance of the tropical colonies, as a means to construct and promote the idyllic, abundant paradise narrative of the Caribbean for tourism industry expansion under empire. Image credit: The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas.

Right: Animated gif edition of Augmented Archive 023 (2024), by Rodell Warner. Using colonial archival images like the one pictured left, Warner gives a sense of spirit, encounter, and disruption to the colonial gaze of the Caribbean archive. Image courtesy of the artist.

Digital subversions in both fictional and historical space and time, Warner’s engagement with the colonial archive is as much an act of love as it is a de-colonial act. Where afrofuturism imagines futures we desperately need, Warner offers another way to dream and show care. His efforts and sincerity offer a palliative care to the memories of those long gone. Part invention perhaps, part invocation on another, these stories carefully woven from fiction and collective memory give us something just as precious as a new future, by giving alternate pasts to those who most deserved to have their stories told.

[1] As part of Operation Legacy, “thousands of documents detailing some of the most shameful acts and crimes committed during the final years of the British empire were systematically destroyed to prevent them falling into the hands of post-independence governments, an official review has concluded.” (Cobain et al., 2012)

[2] “The origins of how the English-speaking Caribbean was (and is) widely visually imagined can be traced in large part to the beginnings of tourism industries in the British West Indies in the late nineteenth century. Starting in the 1880s, British Colonial administrators, local white elites, and American and British hoteliers in Jamaica and The Bahamas embarked on campaigns to refashion the islands as picturesque “tropical” paradises, the first concerted efforts of their kind in Britain’s Caribbean colonies.” (Thompson, 2007, p. 4)

Brand, D. (2002). A Map To the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging. Vintage Canada.

Cobain, I., Bowcott, O., & Norton-Taylor, R. (2012, April 18). Britain destroyed records of colonial crimes. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2012/apr/18/britain-destroyed-records-colonial-crimes

Thompson, K. A. (2007). An Eye For the Tropics: Tourism, Photography, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque. Duke University Press.