Maya Freelon, a multidisciplinary artist and educator from Durham, North Carolina, has created works throughout her career that challenge the Eurocentric status quo of the art world and our wider society. Centering the stories of the Black family, resilience throughout history, and the spectrum of colors and textures representative of her African American heritage, she pulls viewers into the boundless Black imagination. Her immersive installations have been displayed at the Smithsonian Arts and Industries Building, CAM Raleigh, and the North Carolina Museum of Art Sculpture Park.1

Freelon is a fourth-generation artist whose family’s work has touched the world. Her mother, Nnenna Freelon, is a Grammy-nominated jazz songstress and storyteller. At the same time, her father, the late Phil Freelon, was a prolific architect best known for designing the National Museum of African American History and Culture. But it was Freelon’s grandmother, Queen Mother Frances J. Pierce, who was her earliest influence.

On July 28, 1928, in Texarkana, Texas, Queen Mother Pierce was born into a family of sharecroppers—a system of labor that financially captured many of the families who had just tasted freedom into peonage relationships with Southern plantation owners. Queen Mother Pierce joined the Great Migration and landed in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she became a schoolteacher and then a beautician. She was affectionately called “Granny Fanny” by her grandchildren, and Freelon lived with her while attending graduate school in Boston. It was there, in her grandmother’s basement, that she fell in love with one of her signature materials, tissue paper. “Water had leaked onto the paper, causing the colors to bleed,” Freelon shared with Shelly Rose of American Lifestyle Magazine. “It was a metaphor for finding beauty in the simplest form, the fragility of life, and the surprise of a ‘happy accident.’”2

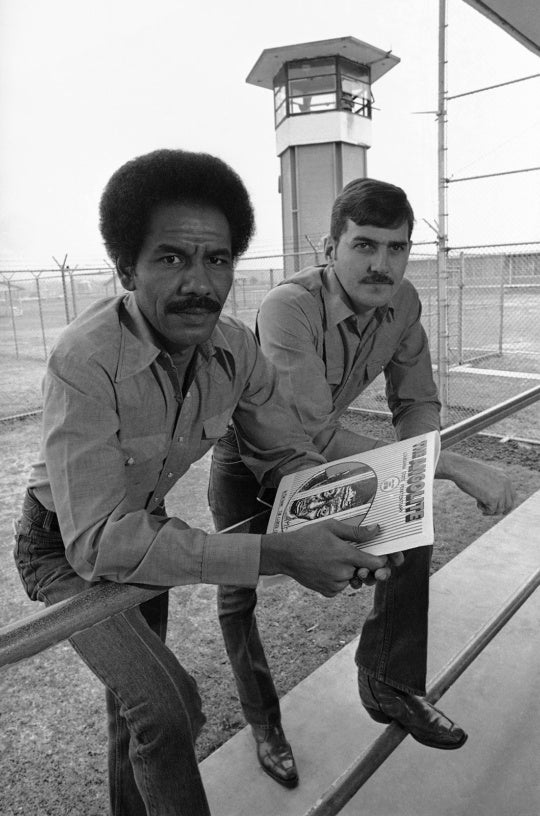

In January 2024, Freelon was selected as one of two artists/scholars in residence for the Library of Congress’s Connecting Communities Digital Initiative. She began her residency by spending hours searching for images representative of Black childhood during slavery, looking deep in the Library’s digital archives for signs of whimsy, sparkle, or delight. Her search proved what she already knew–childhood wonder is rare on a plantation when that child is enslaved.

And still, joy existed.

Her intensive research and signature aesthetic techniques merged in her most recent and personally significant exhibition, Whippersnappers: Recapturing, Reviewing, and Reimagining the Lives of Enslaved Children in the United States, at the Stagville Plantation Historical Site from December 2, 2024, to January 25, 2025. When deciding on a location for Whippersnappers, Freelon contacted Michelle Lanier, director of State Historic Sites at the NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. Freelon recalls, “She’s a black woman. She believes in telling stories, and I saw how she led the Harriet Jacobs Project. I witnessed how careful she and her colleagues were with the artwork created alongside that in a historic space. And I thought, if I’m going to do this, it would have to be under this context.”3

Lanier guided Freelon toward the Stagville Plantation Historical Site in Durham, NC, part of a vast plantation that enslaved over 900 people in the late 1800s. The historic site preserves the Bennehan family house (c. 1799), the Horton Grove slave quarters (c. 1851), a barn (1860), and 165 acres of land where staff, volunteers, and others educate visitors about the site’s history and legacy.4

The ground leading up to the Stagville Plantation had turned into molasses-thick mud when I visited on the final weekend of Whippersnappers. Less than 200 years ago, cloven hooves, padded paws, and the bare human feet of enslaved Africans had walked that lawn. In the eyes of the Bennehans, the Camerons, and their slaver brethren, they were all the same–property and labor. But just like the suckling pig and the knobby-kneed pony, enslaved children were given a small window of time just to be. A good slaveholder knew that putting a child in the fields too early would affect their capacity for labor as an adult; Freelon’s exhibition captures this limerance of innocence.

Whippersnapper means “a young and cheeky or presumptuous person; often with a connotation of ignorance via inexperience.”5 The word’s etymology is an extension of the idea of being the “cracker of whips.” Freelon explained to me as we stood at the exhibition entrance, “A whippersnapper [is] smart as a whip, the whip makes a crack. The crack is not what hurts you. That’s a sound that scares you. Then came the question, ‘Who’s holding the whip, and where is that power going?’ I have the whip. Mmm. I’m the whippersnapper. I’m guiding you through this. If you want to come in.”

Though some fabrication happened in Freelon’s home studio, Whippersnappers was twenty works shaped into ten installations across the grounds of the Stagville Plantation, eight of which were located in the rooms of the Benneham Family House. While Freelon’s signature “bleeding” tissue paper technique shines throughout Whippersnappers, the exhibition also showcased portrait drawings, sculptures, collages, and paintings. “There were some challenges because it is a historic building, not being able to hang framed art on the walls. Mainly, everything has to be kind of self-sustaining.” The restrictions pushed Freelon further beyond her artistic comfort zone, resulting in a body of work unlike anything she had created in the past.

For ten days, she carefully built out the installation in the Big House (standard nomenclature for a slaver’s home). “At first, I was a little worried,” Freelon recalled. “I didn’t know who was going to pop out or what I was going to hear. But Stagville has done such a good job at honoring the descendants who were enslaved, acknowledging the atrocities, and putting ownership on those who did that. I felt like the grounds were ready for revolutionary art to enter in.”

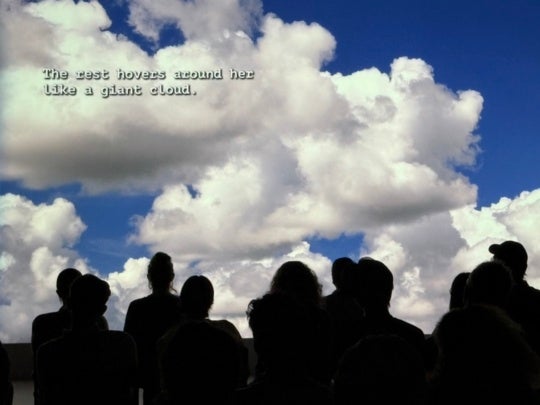

Keys to Freedom, which opened the exhibition and is one of the largest installations in the space, presents two figures, a pregnant adult followed closely by a small child, that are spirit-like, with multicolored tissue paper shrouding their faces and surrounded by a thick winding kudzu vine. Beside them was an antique table presenting three keys lain upon a white handkerchief.

“ There’s this story about a group of Black enslaved people here at Stagville that had to walk all the way to New Orleans,” Freelon told me, explaining her inspiration. “Along the way, they got disjointed from their families, and I thought about what that would mean to somebody who was pregnant or had a young child.” The sculptures’ presentation and the kudzu created a narrative that bridges the shores of Africa and the Americas. When Freelon learned recently that she has Nigerian ancestry, she was attracted to Egungun (Yoruba for “masquerade”), where one obscures their mortality with an elaborate costume to represent the spirits of their ancestors in communal ceremonies and celebrations.6 The kudzu root, representing the new world, brings its own story of displacement and resilience.

“It was brought from Asia by southern farmers here to grow as an anti-erosion technique,” she said. “What happened was it thrived. You got this entity. You put the roots down. It thrives. Now, it’s considered a problem, a nuisance. You got issues with it; you don’t like what happened. To me, it’s a great analogy for Black people in general. How this thick root can be born and you thought we were just gonna come here and work for free and not change, not revolt, not say no. That we can be considered useful and then be considered out of control at the same time.”

Centering the stories of the Black family, resilience throughout history, and the spectrum of colors and textures representative of her African American heritage, she pulls viewers into the boundless Black imagination.

Whippersnappers brought Freelon’s signature techniques to new heights, the exhibition marking a new chapter for the artist’s decades-long critique of the erasure of the Southern African American experience while also allowing her to experiment with new forms and ways to communicate. Many works juxtapose a polychromatic palette with moments of somber white, like with the installation It’s Okay to Cry. Inspired by an image of a Black enslaved girl holding a white baby, captioned “Ida six months and three days,” Freelon confronted the ever-looming sadness awaiting enslaved people, even during a time of supposed innocence and safety. She cropped the photo so only the Black girl’s face was showing, and her gaze fell upon a wooden pulpit encircled by a thick canopy of cascading white streamers hung from the ceiling above.

“This [installation] is collective tears,” Freelon reflected. “These are the tears of everybody. This piece represents the tears of those who were tortured and the tears of the torturer.”

Carrying a century of stories of resilience, remembrance, and resourcefulness gained through her lineage, Freelon continues to explore the spectrum of Black identity in the face of supremacist delusion. “I think that the stories we were told,” she explained, “our survival techniques and mechanisms either passed through and taught to us or just innately within ourselves. I think that’s how we survived.”

[1] Marlowe, Karlie. 2024. “PRESS RELEASE: Artist Maya Freelon Debuts Whippersnappers in Durham, North Carolina This Fall.” Maya Freelon. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55322f45e4b09a66347681de/t/66c38bf5baa53b34a992c443/1724091386404/Press+Release_Whippersnappers+Exhibition+ftg.+Maya+Freelon.pdf.

[2] Rose, Shelley. 2018. “Bleeding Art: Maya Freelon Asante.” Americanlifestylemag.com. American Lifestyle Magazine. 2018. https://americanlifestylemag.com/life-culture/editorial/bleeding-art-maya-freelon-asante/.

[3] Camille Bacon, Daria Simone Harper, and Niara Simone Hightower, “‘Let Us Draw Nigh’ Remembering a Sojourn for Harriet Jacobs,” Burnaway, August 1, 2024, https://burnaway.org/magazine/let-us-draw-nigh-remembering-a-sojourn-for-harriet-jacobs/

[4] “History of Historic Stagville,” History | NC Historic Sites, accessed March 10, 2025, https://historicsites.nc.gov/all-sites/historic-stagville/history.

[5] “Whippersnapper – Wiktionary, The Free Dictionary,” Wiktionary, February 15, 2025, https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/whippersnapper.

[6] Wikipedia contributors, “Egungun,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Egungun&oldid=1278921827 (accessed March 24, 2025)

View more of Maya Freelon’s work on her website at mayafreelon.com/.