John Berger first made reference to the male gaze in 1972 in Ways of Seeing. The term was then coined and popularized in 1975 by feminist film critic Laura Mulvey in her essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” She writes, “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy [sic] on to the female form which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role, women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.”

Author Jess Zimmerman calls this the “patriarchal panopticon” in Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology, referring to our living under the ever-present, always-looming eye of a male gaze, in media and movies, books and magazines, on television. A gaze that impacts not only how most cis men see women—in relationship to their own desires—but how many women see themselves. The male gaze dictates the degree to which we measure up to patriarchal standards of accepted desirability, informs the ways we contort ourselves to make up the difference when we don’t.

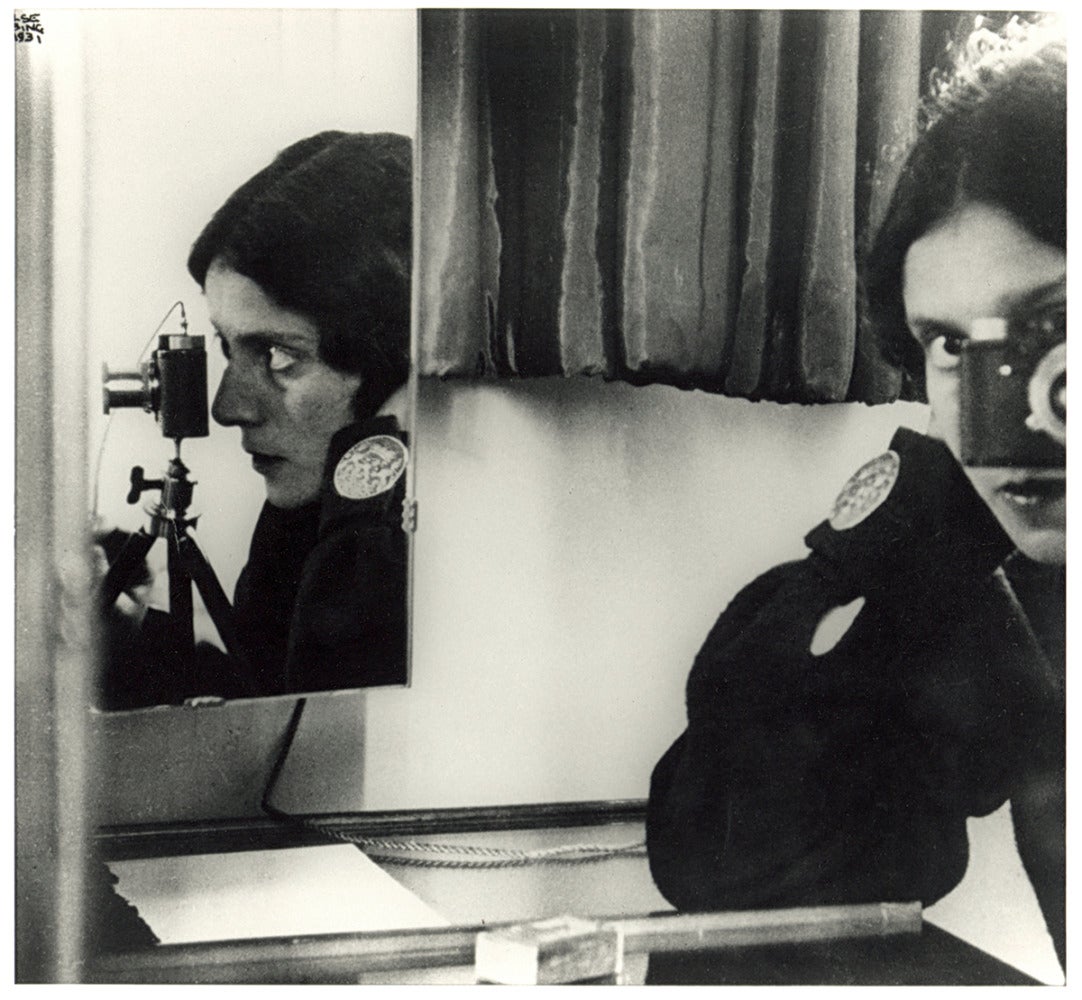

It’s no wonder then that walking through the High Museum of Art’s Underexposed: Women Photographers from the Collection feels to me like breaching the surface of water after being under it for too long, that first big gulp of cleaner air. There is nothing of the male gaze here. The exhibition, on view through August 1, offers a loosely chronological and abbreviated look at the profound and important, though often erased, contributions of women to the field of photography over the past 100 years. Many of the works, pulled from the museum’s expansive permanent collection, are on view for the first time.

In an effort by co-curators Sarah Kennel and Maria Kelly to resurrect the stories of the women behind the lens, the photographs’ accompanying name plates also include biographical information about the photographers and the context in which the images were made. “This is not typical for our exhibitions,” says Kelly, who spoke with us about the exhibition via email, “but we wanted to give visitors the chance to learn more about every piece while in the galleries—it helps to shine a light on every artist, regardless of whether they have name recognition or not.”.

Alongside stunning works from art world mainstays like Sally Mann, Nan Goldin, Diane Arbus and Mickalene Thomas, there are also photographs from women whose names viewers may be discovering for the first time. These include: Louise Dahl-Wolfe, the first woman staff photographer at Harper’s Bazaar; Marion Palfi, who fled the Nazis in 1936 and went on to document the ravages of racism and poverty in the United States; photojournalist and war photographer Kael Alford, who documented the struggles of women during the Iraq War; Sheila Pree Bright, a celebrated Atlanta-based photographer who travels with and photographs the movement for Black Lives; and Susan Meiselas, who, says Kelly, photographed and recorded interviews with carnival strippers in the 1970s, “giving a voice to women who were mainly viewed as objects for spectacle.”

Kennel, the High’s Donald and Marilyn Keough Family Curator of Photography, warns against the suggestion of a common, unified female gaze in the exhibition. “That runs the risk of flattening the works of art and erasing differences among makers,” she says via email. Though she does concede that “we can and should ask how the conditions of making a photograph are shaped by myriad factors, including the gender or gender identity of the maker at different moments in history.”

But I don’t know how else to describe the way it feels, as a woman myself, to walk through an exhibition like Underexposed, and see what I’m seeing. If there is a male gaze through which all of us are forced to view the world, these photographs are most certainly its opposite, celebrating in diverse and exceptional ways everything from flowers and architecture, to war and adolescence, from the domestic sphere to movements for social justice.

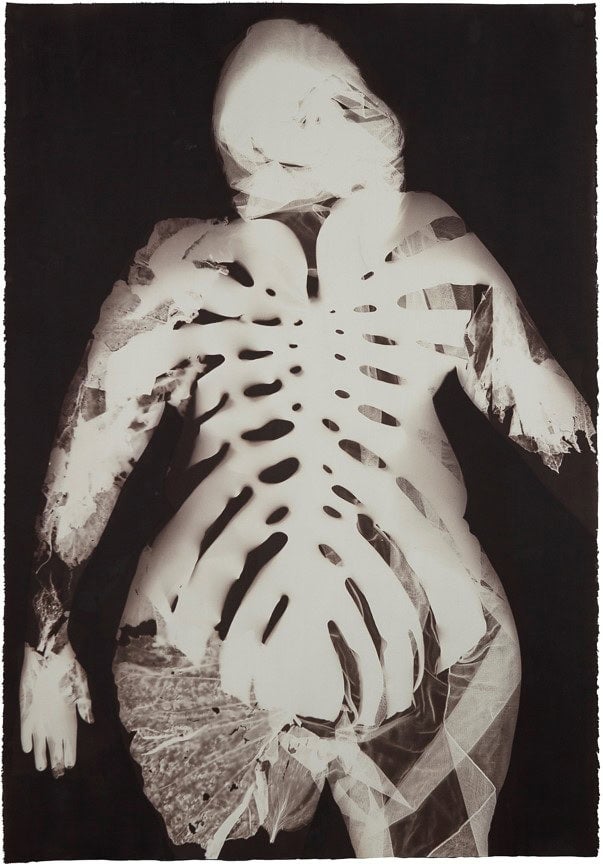

Consider Joyce Neimanas’ Daytime Fantasies (1976), for example. We see a literal co-opting of the hypersexualization of women’s bodies for male consumption. For this image, Neimanas enlarged a still from a 16mm pornographic film, added color, and annotated it with text taken from the famous 1953 Kinsey Report, Sexual Behavior of the Human Female. Across the woman’s ribs it reads, “Some females have daytime fantasies which may so arouse them that they reach orgasm without any physical stimulation. It is only one male in a thousand who can fantasy to orgasm.” A divorce from its original context that provides an absolution from shame; an image of objectification reclaimed; a woman’s desire celebrated in active defiance rather than displayed in passive titillation for the sake of male fantasy.

The liminal space of a 12-year-old girl’s adolescence, seen through Sally Mann’s Juliet in a White Chair, does similar work. Mann captures the truth of self-conscious sensuality in her subject without ever coming close to exploitation, without ever being in dialogue with, say, Nabokov’s Lolita, ignorantly celebrated by many as the consummate tome on how to see teenage girls and engage with what the male gaze tells us is their treacherous sexuality. Instead, in Mann’s deft hands, the image becomes a dissenting testimony to the intimacy, power, and magic of teenage becoming that most viewers who identify as women, or who were raised as girls, can instantly identify.

These are the most arresting photos. The ones, like Mann’s, that the photographers took of other women and of themselves. I am not looking at me when I view them, but I am still seeing women in a way that I intimately understand and recognize, that feels both safe and free. In photographs like Carrie Mae Weems’ self-portrait, Untitled (1996), Susan Meiselas’ Lena’s First Day, Essex Junction, Vermont, (1973), Edith H. DeLong’s Repose (1894) or Nancy Floyd’s Thirty-five Years series, I am looking in a way that makes me, as the viewer, and women, as the central figures, feel seen rather than exposed, subjects rather than objects.

In Underexposed, women are temporarily liberated from the confinement of the frame as created by the panoptical male gaze. We get to move beyond seeing as an act of consumption, beyond Mulvey’s to-be-looked-at-ness, and into a space where seeing becomes witnessing, and witnessing becomes a kind of liberation. Through the lenses of these photographers, the panopticon becomes an open window through which we can more clearly see each other and ourselves.