1.

Lorraine O’Grady’s living was a poem about irreducibility.

2.

These sentences coagulated around a waxing moon, around the sentinel dangling in the gaping sky that presided over her Nine Night. Penned as her soul reached up through her mouth and climbed out to begin its journey into the ever-elsewhere, given her Jamaican heritage, only appropriate that I’d wait until then to begin elegizing. This is the second of eight verses, one for each traipse I imagine she took before puncturing the veil to become a different kind of star.

3.

In her daring essay, Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity (1992, 1994), O’Grady wrote: “First we must acknowledge the complexity, and then we must surrender to it.” While articulated in the context of the “reclamation of the body as a site of black female subjectivity,”1 I might expand the ground this statement’s exhale covers to celebrate the immense wingspan of her dissident imagination. Working across performance, collage, photography, curatorial interventions, writing, and even appearing in a music video by ANHONI, she possessed an unrelenting errantry, railing against the expectation that she codify herself within the neat boundaries of a single medium.2

O’Grady was the definition of a “multihyphenate” or “interdisciplinary artist” before such vocabularies began appearing across instagram bios and press releases alike. To this end, she shares, “I am a breadth artist: I make incisions into the skin of culture and then stuff as much of myself into each little incision that I make, so that nobody could ever think I only do one kind of thing, or that I am only one kind of person.” Indeed, she taught those of us who kneel at the altar of her oeuvre about what it takes to not only challenge tradition, but to obliterate the apparatus of disciplinarity and its attendant violences entirely, to be unabashedly everything we are in its full and illegible expanse.

Further, across the fifty splendorous years of her career, she greatly expanded the realm of the utterable, cleaved open the scope of the sayable, and ventured into the territory of the taboo with an uncompromising dedication to the project of giving Black women a reflecting pool of language—both visual and written—through which to confront and contemplate ourselves clearly. “For me, the hardest part was lacking the language to describe myself,” said O’Grady, and now she holds spiritual court as one of the foremost linguists of the Black femme avant-garde, for as she gave herself the gift of lexicon she passed it on to us, her fellow guardians of the Black feminist future, too.

4.

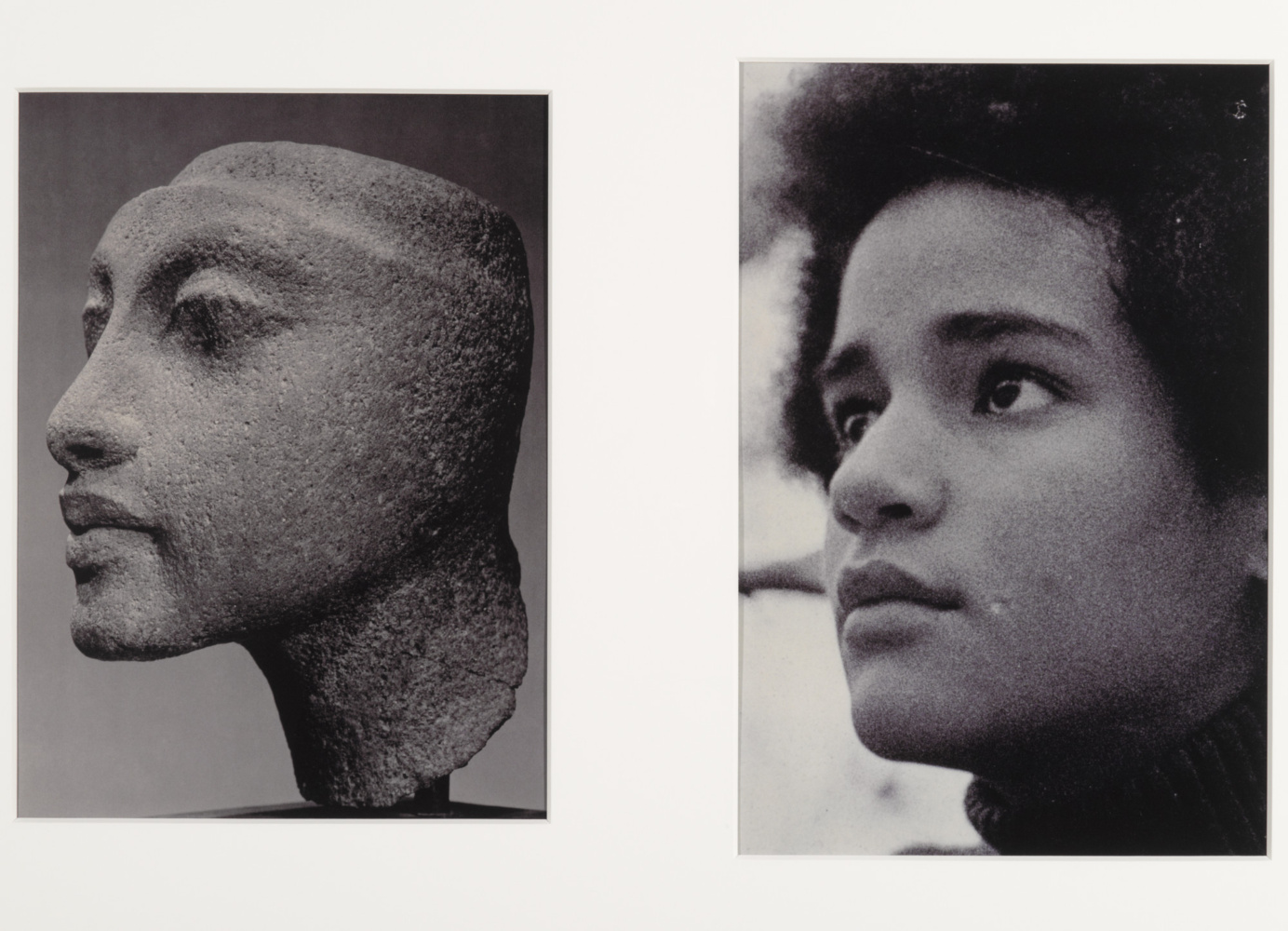

Her work reworlded my life first in February of 2020. I was a junior at Smith College and had whimsically signed up for a tour of Black Refractions: Highlights from the Studio Museum in Harlem.3 In it was an artwork from O’Grady’s 1980/94 series Miscegenated Family Album: (Sisters IV), L: Devonia’s sister, Lorraine; R: Nefertiti’s sister, Mutnedjmet (1980/88).4 The diptych features a grisaille-esque portrait of the artist with her hair pulled back and eyes poised valiantly towards an unfixed horizon. Beside O’Grady is Nefertiti’s sister, Mutnedjmet, carved assiduously in stone. Thematically reminiscent of Lucille Clifton’s poem “to merle” (1980) wherein she writes “last time i saw you was on the corner of / pyramid and sphinx, / ten thousand years have interrupted our conversation / … what i’m trying to say is / i recognize your language and / let me call you sister, sister, / i been waiting for you,” here, O’Grady connects ancient Egypt to Black contemporary life. In so doing, she forges a document of relation and ancestry that is trans-geographical, a-temporal, and decisively insouciant to the notion that inheritance is fixed and determined only by one’s biological family.5

Looking back at Sisters IV, I am fixated on the way O’Grady’s body seems to bend the light around it, on how the space encircling her forms an entanglement between thick, gravitational shadow, and pure luster. The chiaroscuro of her portrait rhymes with the swelling moon under which I write this; It’s hugged by a lustrous halo of etherous glow, as if the planet itself is expelling luminosity into its pitch-black surroundings. Likewise, the artist shines like a galaxy and around her lies the indeterminate dark, a morphology in which she might surrender to that thrum of the interior and whisper a song of rogue sovereignty into the night.

5.

A few weeks after my first encounter with her work, I marched eagerly through the New England winter, insulated by a humming elation to see Dr. Stephanie Sparling Williams, author of Speaking Out of Turn: Lorraine O’Grady, in conversation with the artist.6

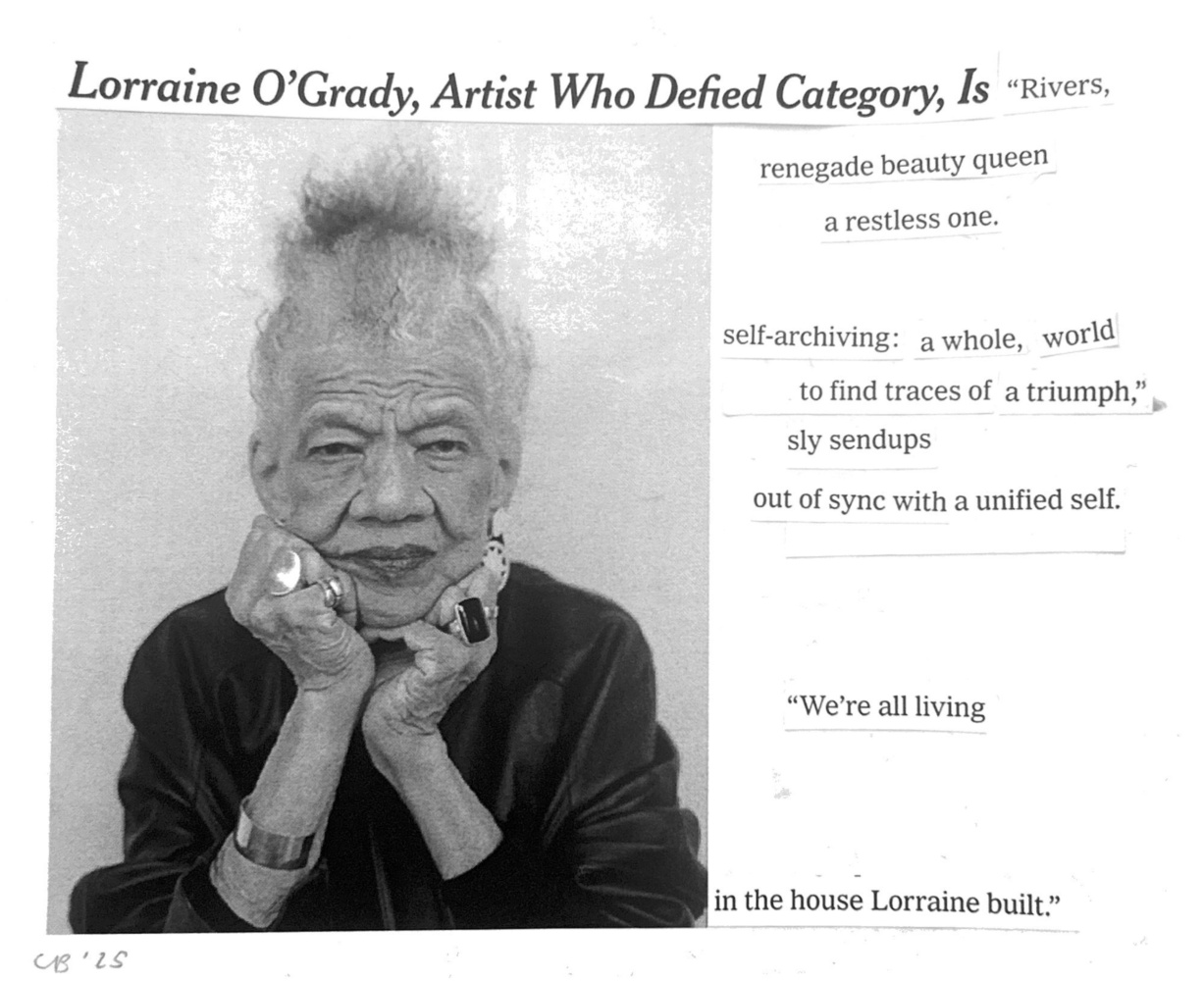

O’Grady’s was the sort of presence that makes you straighten your back—just as in the case of her work, she herself seemed able to marshall the force of the elements: the air changed shape as soon as she strode on stage in her signature all-black outfit and cowboy boots (a woman after my own heart, she had three closets: “one filled with black tops, another with black pants and leggings, and a third with black leather jackets,” notes Aruna D’Souza).7 Rivers of silver cascaded like shored relics from her slight wrists and earlobes and her mohawk, with its arrow-like form, seemed for those 90-minutes to be a wayfinding tool pointing listeners toward the bravery it takes to inexorably embrace the outer bounds of their own wonder, and then make something out of it.

This part of the story ends where my pen falls now: Black Refractions as a whole, but O’Grady’s work in particular, enamored me so much that I abandoned my studies in chemistry and committed, instead, to expanding the vocabulary with which we apprehend and interpret the work of Black contemporary artists; a pursuit O’Grady was deeply committed to as well.

In 1980, O’Grady’s alter-ego, Mlle Bourgeoise Noir, interrupted an opening at Just Above Midtown Gallery and introduced those gathered there to what would later become one of her most iconic works.8 Donning a dress made from 180 white gloves and carrying “a white cat-o-nine-tails made of sail rope from a seaport store” adorned with white chrysanthemums, she lashed herself and proclaimed that “BLACK ART MUST TAKE MORE RISKS.”9 The performance was a clarion call, a rumbling thunder clap, her means of addressing her hunger for an “art world” more capable of subverting the status-quo. I understand Mlle Bourgeoise Noir as an embodied vehicle of criticism, as a piercing demand for more from herself and her peers. The inertia of those evocations remain ablaze in the atmosphere today as myself and so many artists and writers alike continue to reel in the conditions we need to “TAKE MORE RISKS” and venture to work in experimental forms that reprove the boundaries of commercialization.

6.

O’Grady’s offerings have since settled into the interstitial space of my cerebrum, refusing to budge and thus holding me to a standard of unremitting courage.

Come March of 2021, I joined forces with the artist Sydney Vernon to pen an open letter in response to the film Black Art in the Absence of Light (2021), which turned back to Mlle Bourgeoise Noir as a seminal site of inspiration. Then, in September of 2022, I came to face with a photo of the artist (which accompanied a stunning profile of O’Grady by Doreen St. Felix) suspending a katana in a deft diagonal over her shoulder and confronting the camera as if to say try me, I dare you.10 In moments of duress, I still conjure this image in my mind’s eye for an uncut dose of audacity and imagine how that blade may have sung as she unsheathed it, how her gestures swept the room as she sliced through the air. A month later, I journeyed to Venice for The Loophole of Retreat, where O’Grady gave us more language to live alongside by expressing: “We are no longer afraid of being lonely. We are no longer trying to connect, we are connected. We are no longer standing still, defending a position. We are going forward. This movement is unstoppable.”11

7.

Unstoppable indeed. In October of 2024, Dr. Sparling Williams, as the Andrew W. Mellon Curator of American Art at the Brooklyn Museum, inaugurated Toward Joy, a monumental rehang of the museum’s American art collection, housed within the same walls that welcomed O’Grady’s retrospective Both/And in 2021.12

Described by Dr. Sparling Williams as “mutiny in the galleries,” she devised a reshuffling of the collection based on Black feminist principles. Asking questions like “how might American art be experienced at this moment?,” the rehang contravents orthodox practices around the display of historical materials that depend on geographic and temporal coherence as well as the elision of who and what canonical artworks were so often made at the expense of. Instead of stowing away creations that hail from the dawn of empire and represent dogmatically destructive ideologies, Dr. Sparling Williams offers a framework for encounter that is rigorously redemptive without being inappropriately optimistic. The capacity for such insurgent imagination within a normative institution is influenced by the curator’s deep study of and relationship with O’Grady which involved a rubbing off of the latter’s ability to “acknowledge” and “surrender” to complexity.

A critical facet of the rehang was Dr. Sparling Williams’ devising of the Black Feminist Round Table: a group of artists, scholars, writers, and scientists, who gathered across the span of nearly a year to offer feedback on the eight frameworks she put forth. One such framework, which Leslie Wilson, associate director for academic engagement and research at the Art Institute of Chicago, and I worked on, took up O’Grady’s Black and White Show as a point of departure, which served as yet another opportunity to be completely transformed by her intrepid, sharp, and innovative approach to contemporary art—both its making and its conditions of display and interpretation.13

Mounted in 1983 and curated by O’Grady, the Black and White Show brought together Black and white artists and included artworks made exclusively in black and white “as achromaticity heightens similarities and flattens differences.” The exhibition was a dagger into the chest of the rhetoric of “quality” that was so often levied then as a means of excluding artists of color and, particularly, Black artists from their full participation in art historical evolution. Though the exhibition was not robustly reviewed, it lives on now by way of the Counterparts gallery at the Brooklyn Museum, wherein O’Grady’s achromatic approach is brought forth to put artworks from disparate places, times, and aesthetic traditions in direct dialogue and where a work from the series that first seduced me so, Miscegenated Family Album (1980/88), is triumphantly on view.

8.

Indeed, the roaring tract of Lorraine O’Grady’s practice calls for a close read between the cresting waves of the tome that survives her. Running the crystalline water of her offerings through my fingers, what endures the evaporation is that she taught us about what it takes to not only “move the needle,” but to shatter the apparatus entirely.

[1] Lorraine O’Grady, “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” Lorraine O’Grady, 1992, https://lorraineogrady.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Lorraine-OGrady_Olympias-Maid-Reclaiming-Black-Female-Subjectivity.pdf.

[2] ANOHNI, “ANOHNI: MARROW,” November 30, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rb9XECErMlc.

[3] “Black Refractions,” Studio Museum in Harlem, April 8, 2022, https://www.studiomuseum.org/magazine/black-refractions.

[4] “Sisters IV (L: Devonias Sister Lorraine, R: Nefertitis Sister Mutnedjmet), From the ‘Miscegenated Family Album,’” Studio Museum in Harlem, 1980/88., https://www.studiomuseum.org/artworks/sisters-iv-l-devonias-sister-lorraine-r-nefertitis-sister-mutnedjmet-from-the-miscegenated-family-album.

[5] Two-Headed Woman (The University of Massachusetts Press, 1980).

[6] “Speaking Out of Turn by Stephanie Sparling Williams – Hardcover,” University of California Press, n.d., https://www.ucpress.edu/books/speaking-out-of-turn/hardcover.

[7] “We Were All Just Catching up to Lorraine O’Grady,” The New York Times, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/16/arts/design/lorraine-ogrady-artist-legacy.html.

[8] “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire – Lorraine O’Grady,” Lorraine O’Grady, October 12, 2022, https://lorraineogrady.com/art/mlle-bourgeoise-noire/.

[9] “Radical Acts,” MoMA, 2022, https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/290/3758.

[10] Doreen St Félix, “Lorraine O’Grady Has Always Been a Rebel,” The New Yorker, September 29, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-new-yorker-interview/lorraine-ogrady-has-always-been-a-rebel.

[11] Loophole of Retreat: Venice, “Lorraine O’Grady and Simone Leigh in Conversation, Loophole of Retreat: Venice,” January 13, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KGrlp-HRp54.

[12] “Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And,” Brooklyn Museum, n.d., https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/lorraine_ogrady.

[13] “The Black and White Show – Lorraine O’Grady,” Lorraine O’Grady, October 3, 2022, https://lorraineogrady.com/art/the-black-and-white-show/.