Unbeknownst to many across the U.S., even those in North Carolina, Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, has a one-of-a-kind contemporary art collection. It is a collection that students have been entirely responsible for amassing since the early 1960s. Once every four years, now every three thanks to increased funding, the university takes a small group of students to New York City, many visiting for the first time, and gives them $100,000 to buy art. So far, these students have accrued over two hundred works in various mediums for the Mark H. Reece Collection of Student-Acquired Contemporary Art, from painting to photography to electronic sculpture. In developing each trip’s selection, the participants have only one rubric from the institution: purchase contemporary artworks that reflect the times.1

It’s an assignment the students take seriously, fearless in their embrace of artists dealing with sensitive political and cultural issues. In the last few decades alone, they’ve acquired potent works by transdisciplinary American artist Martine Gutierrez, Iranian-American photographer Shirin Neshat, and Palestinian artist and filmmaker Emily Jacir, among many others. In 1993 students acquired works by American artists Glenn Ligon and Nancy Spero that were featured in that year’s watershed Whitney Biennial, at the time criticized as the “identity politics” show.

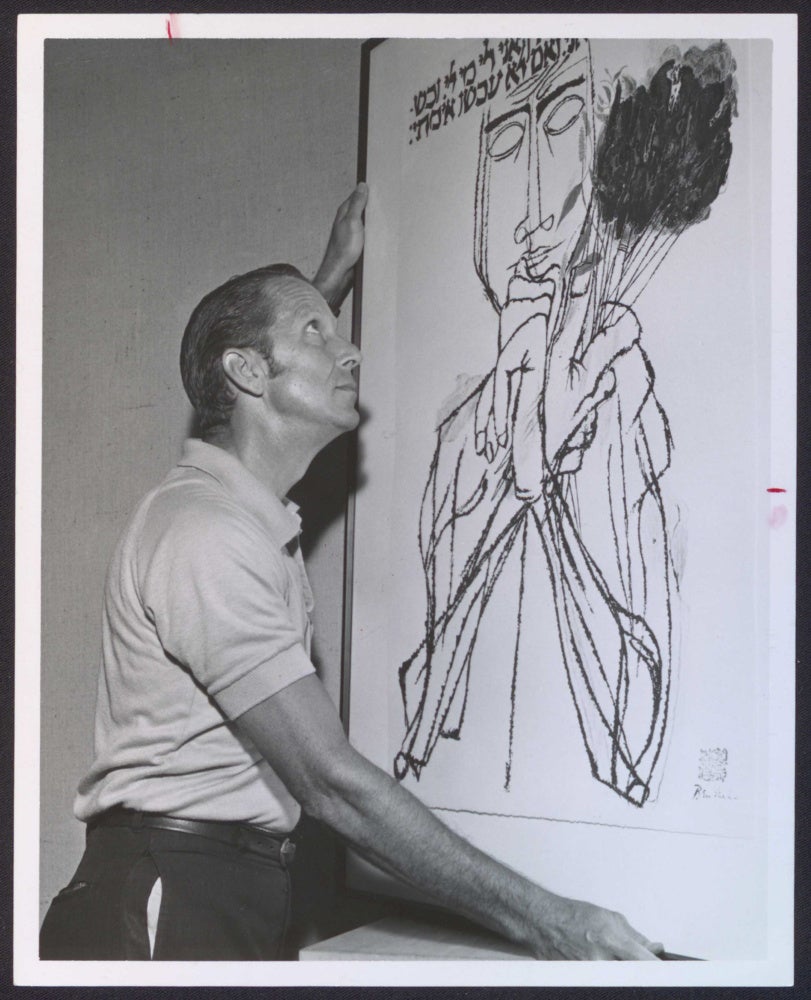

The students are savvy, too: In 2021 they purchased a piece from Pakistani painter Salman Toor on the heels of his first institutional solo exhibition. Earlier this spring, they bought a Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, whose work is featured in the Nigerian Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale.2 The list of acquisitions from the program’s early years, mostly consisting of American artists, is especially surprising given the university’s slim acquisitions budget and their then-Baptist affiliation.3 There is a male nude by Paul Cadmus; a drawing by Keith Haring from his first major exhibition at Tony Shafrazi Gallery; an eight-foot-tall Alex Katz; an Elaine de Kooning—not a Willem—purchased during the inaugural trip at a discount thanks to student negotiations and a plea to Elaine herself.

“Wake Forest trusts students to make these decisions, to purchase works with no board, no sort of approval process,” Jay Curley, Associate Professor of Art History, told me, reiterating the student’s autonomy throughout the undertaking, another surprising aspect of the program.4

Acquisition discussions resemble jury deliberations in a high-profile trial: the young collectors sequester together, sans faculty, and debate into the wee hours to make the final call. This past year, the eight students were up until three in the morning finalizing their selection.

Technically, Wake Forest has nine art collections, but the Mark H. Reece Collection of Student-Acquired Contemporary Art is their most unconventional. It’s also their most visible; the works are now displayed throughout the Benson University Center, which serves as a home base for students and offers amenities such as a food court, study lounges, meeting rooms, and offices for support organizations, including the Student Union, the LGBTQ+ Center, Intercultural Center, and more.5

Mark H. Reece, the collection’s namesake, started the program in 1963 before Wake had a single art collection or even an art department. Heavily involved in student life as a dean and advisor, Reece always envisioned an art collection for students, handpicked by students, and holding space in their everyday lives.6

Reece hoped the collection would bring awareness to the university’s artistic shortcomings, inspiring the creation of an art department and more art appreciation across the board. Looking at historical context, it’s easy to see why such a mission took hold. For Reece’s generation, championing the art of our times was a tinge more patriotic than purely market driven, with modernism seen as indicative of individualism and American inventiveness during the early years of the Cold War. Despite a sixties shift towards Pop and pluralism, the historical precedent was all the more reason for Wake to get into art and the art-collecting game.7

To make his dream a reality, Reece scraped together leftover funds from other student organizations and drove up a couple of fellow staff members and students to embark on his artistic experiment. By 1969 the program had earmarked around $35,000 for acquisitions, but the trip was still undertaken on a shoestring budget compared to other university endeavors; alumnus J.D. Wilson, who participated in that year’s art-buying trip, recalled, “To make the trip more affordable, I drove my car, and we stopped overnight at [classmate] Harv Owen’s home in Pennsylvania.”8

Early iterations of the venture involved writing letters to galleries and paging through the bundles of catalogs they’d send in return. Also, the collection’s current holding location, Benson, wasn’t built until 1990; in prior years, the student’s selections would be scattered across campus study rooms and dining halls.

Alumna Terry Angelotti, who was on the 1989 art-buying trip, remembered a packed schedule: moving through different neighborhoods and dashing from gallery to gallery on her first-ever trip to New York City. When asked about the ensuing deliberations, “I don’t know if heated is the right word,” she told me, “but we were really putting our whole selves into it. It wasn’t casual at all,” she stressed. “We all had strong opinions that, at the beginning of the night, were not in sync.”9

One artwork that came to steer the conversation, and led to consensus quickly, was a seven-foot-by-six-foot Robert Colescott painting titled Famous Last Words: The Death of a Poet (1988). Colescott is known for layered, irreverent works that unflinchingly bring issues of race and sex to the forefront. His canvases satirize white supremacy and expose its constant, central place in American culture through outlandish, stereotypical figuration and dense picture planes. Humor is a diversion and a tactic; large, expressive paintings with caustic figures in chaotic situations provide a shock. The artist wrote, “It’s the first impact that people get. They walk in and say, ‘Oh wow!’ And then, ‘Oh shit’ when they see what they have to deal with in subject matter. It’s an integrated ‘one-two’ punch; it gets them every time.”10

Famous Last Words depicts a crowded scene devoted to lauded American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. Considered one of the first Black poets to gain national acclaim and recognition, Dunbar rose to prominence in the mid-1890s, and his influence stretched far beyond his early death at thirty-three. Dunbar, in Colescott’s painting, is telling his life’s story from his deathbed, and his hazy memories surround him like a series of ghastly visions rendered in a lavish, cartoonish style. Vignettes hint at his alcoholism, partially as a way to self-medicate his chronic cough, and the instances of racial violence and inequality that were likely to affect a Black man in Dunbar’s time.11

“I was double majoring in art and politics,” Angelotti recollected, “and I was interested in art making a political statement and offering social commentary.” Formally speaking, Colescott’s work aligned with her interest in Mexican muralists like José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, and, she added, “the painting was visually beautiful and so powerful.”

“I don’t remember feeling concerned or feeling like we were being radical,” Angelotti said about the painting’s acquisition. “I don’t think we realized it would be as controversial as it was.”

Three years later in 1992, after Famous Last Words was installed in Benson, it was vandalized—a pointed disruption that exceeded the wadded-up gum, penis drawings, and table scuffs that had besmirched works acquired in decades prior. The blonde white woman, depicted in the middle left having sex with a young Dunbar, was defaced—her face and skin covered with markings from a black felt-tip pen.

Wake Forest soon brought Colescott to campus to repair and restore the painting for future generations, hosting a discussion with the artist and using the instance as an educational opportunity. Famous Last Words is in pristine condition these days, but after a series of record-setting auction sales for the late artist, the painting sits in storage—another work from the university’s collection deemed too valuable for public display.12

“It’s not an either/or,” Jennifer Finkel, Ph.D., the Acquavella Curator of Collections at Wake Forest, told me. She stressed that while living with the student-acquired work can be a wonderful idiosyncrasy of the collection, “the reality is: we don’t have a safe place to put some things on campus.”13

Calls for a permanent space only grow louder, especially as works age, grow in value, or demand more care than hallways can provide. A dedicated space would also bring awareness of the collection to people outside Wake’s orbit. Considering that North Carolina’s major state museum is hours away, a high-caliber, in-person collection available is an especially valuable teaching tool and could be a regional attraction.

As the school’s newspaper, The Old Gold & Black, reported, a 2017 summation from Kevin Murphy, Ph.D., the Eugénie Prendergast Senior Curator of American and European Art at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, attempted to ring the alarm bells. Murphy wrote that, despite the mission behind the display, “works in Benson are so visible as to have become invisible.” He added that, “[Wake Forest University] has a choice—it can continue to let its collection deteriorate or not. The display conditions I witnessed are, frankly, appalling.”14

These days, participating in the art-buying trips is competitive. A mere handful of applicants are accepted, around six to eight students in recent years, save for 2021 when pandemic-fueled digital options helped the endeavor welcome thirteen. Students spend the semester prior in a Contemporary Art and Criticism class, researching hundreds of artists and presenting their findings regularly.

“I paid attention to what the museums were doing,” senior art history and economics double major Jason Najjar told me, along with what critics had their eyes on. “Finding an artist that has writing on them is important because it means they’re starting to enter the canon—for better or worse.”15

Senior art history and communications double major Georgia-Kathryn Duncan added, “Whenever we thought about an artwork, we would ask ourselves, ‘What kind of student would enjoy this? Is it only the art history people? Or would a physics student be able to connect with this? How would this work with other pieces in our collection? What gaps would it fill?’”16

It’s an assignment the students take seriously, fearless in their embrace of artists dealing with sensitive political and cultural issues.

Once the students are in New York City, they call galleries and negotiate discounts, encountering varying levels of respect from their peers in the art world. Some dealers glance at Professors Curley and Finkel, looking for them to jump into the exchanges, but in this instance, the young collectors steer the conversation. The students hold the purse.

“Artwork . . . opens up a conversation that can be really hard to bring up in a classroom or social setting,” Duncan told me. “A depiction of something that’s hard to put words to.” Her statement serves as a reminder of the collection’s unique power at this moment. As art and art appreciation continue to be culturally devalued and higher education faces a litany of crises driven by an ever-polarized and increasingly anti-intellectual culture, does a collection like this one offer some semblance of a solution?

At the program’s sixtieth-anniversary exhibition, Angelotti noticed a group of students discussing Alex Katz’s Vincent with Open Mouth (1970), purchased on the 1973 trip. The oversized painting shows Katz’s ten-year-old son with an ambiguous expression, conveying wonder, boredom, or perhaps an unresponsive stupor. “The students were talking about how jarring it is,” Angelotti observed, glad the class finally had the opportunity to view the painting in a gallery setting and from an appropriate distance. “I wanted to go over there and say, ‘Yeah, I know. Try doing your calculus homework under his eyes.’”

[1] Jennifer Finkel, foreword to The Mark H. Reece Collection of Student-Acquired Contemporary Art (Winston-Salem: Wake Forest University, 2023), pp. 4–5.

[2] Kim McGrath, “2024 student art-acquisition trip selections unveiled,” Wake Forest News, April 19, 2024, https://news.wfu.edu/2024/04/19/2024-student-art-acquisition-trip-selections-unveiled/.

[3] “History of Wake Forest Graduate School,” Wake Forest University, accessed June 30, 2024, https://graduate.wfu.edu/history/.

[4] Interview with the author, May 3, 2024.

[5] Kim McGrath, “Wake,” Wake Forest News, February 14, 2022, https://news.wfu.edu/2022/02/14/wake-forests-premier-art-collection-gets-a-new-name-and-lots-of-love/.

[6] Finkel, foreword to The Mark H. Reece Collection, pp. 4–5.

[7] This is Serge Guilbault’s main argument in his book How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983). Juliet Steyn’s review summarizes: “The outcome, Guilbault argues, and convincingly so, was that abstract expressionism achieved its success not solely on aesthetic or stylistic grounds . . . but because of the ideological use to which it was put.” See Steyn’s text in Oxford Art Journal 7, no. 2 (1984): pp. 60–64.

[8] J.D. Wilson, “A Vision for the Arts. A Distinction for Wake Forest,” in The Mark H. Reece Collection, pp. 10–11.

[9] Interview with the author, June 21, 2024.

[10] Roberta Smith, “Robert Colescott Throws Down the Gauntlet,” The New York Times, July 7, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/07/arts/design/robert-colescott-new-museum-painter-race.html.

[11] “Paul Laurence Dunbar,” Poetry Foundation, accessed June 30, 2024, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/paul-laurence-dunbar.

[12] Christa Dutton, “Reflecting the Times,” The Old Gold & Black (Wake Forest University), April 12, 2023, https://wfuogb.com/20067/features/reflecting-the-times/.

[13] Interview with the author, May 3, 2024.

[14] Dutton, “Reflecting the Times.”

[15] Interview with the author, May 6, 2024.

[16] Interview with the author, May 9, 2024.

To learn more about the work at Wake Forest University’s Mark H. Reece Collection of Student-Acquired Contemporary Art, read more here.

This essay is the first feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Knock Knock.