The house was revealed as if standing there from pure memory against a now moonless sky. For the length of a breath, everything stayed shadowless, as under a lifting hand, and then a passage showed, running through the house, right through the middle of it.

Eudora Welty, Losing Battles

I.

Sewanee, Tennessee

The end of the road. No dogtrot in sight. I’ve driven back and forth along the stretch of gravel, peering out the window, trying to catch a glimpse of a cabin through the trees.

On my third pass I see two men standing in the woods, a few yards back from the road. There’s a younger man, benevolently dadlike, a short reddish-brown beard. With a blend of impatience and affection, he seems to be looking after the older guy. He’s spindly, gray-bearded, and rests against a tree. Despite the humid heat, a knit beanie covers his head. In both hands he’s holding tree branches.

“Are you looking for something?” the younger man asks as I get out of the car.

I introduce myself, tell them I’m looking for a dogtrot. It’s supposed to be nearby.

“I’m Dave,” the younger man says. “That’s Thom.”

Thom is alert. “You’re looking for a what?” he says.

“A dogtrot. It’s like an old cabin with a hallway going straight through the middle that’s open to the outside. Almost like two cabins put together with one roof. A guy I know used to live in one somewhere around here.”

Dave doesn’t know. Thom is thinking hard. His eyes are squinted and searching, his body slack against the tree.

“Yeah . . . I think I remember that cabin. Like with a big porch going through? But I can’t remember where it is. You’ll want to talk to the Stapletons. They’ll know. They know this whole area. They’re in the second house on your right.” He points with one branch.

As I thank them and start back to the car, Thom’s eyes take a mischievous glint. He raises both branches to his sides like a pair of wings, then points them straight at me and shakes, the leaves rattling up a loose rhythm.

“I bless you on your quest!”

The quest had begun three days prior, in North Carolina, when after some humming and hawing I’d decided to drive around the South for a week, seeing as many dogtrots as I could. But the root of the quest was years old. It was these words in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, photographer Walker Evans and writer James Agee’s uneven masterpiece about tenant farmers in the Depression-era South:

Two blocks, of two rooms each, one room behind another. Between these blocks a hallway, floored and roofed, wide open both at front and rear: so that these blocks are two rectangular yoked boats, or floated tanks, or coffins, each, by an inner wall, divided into two squared chambers.1

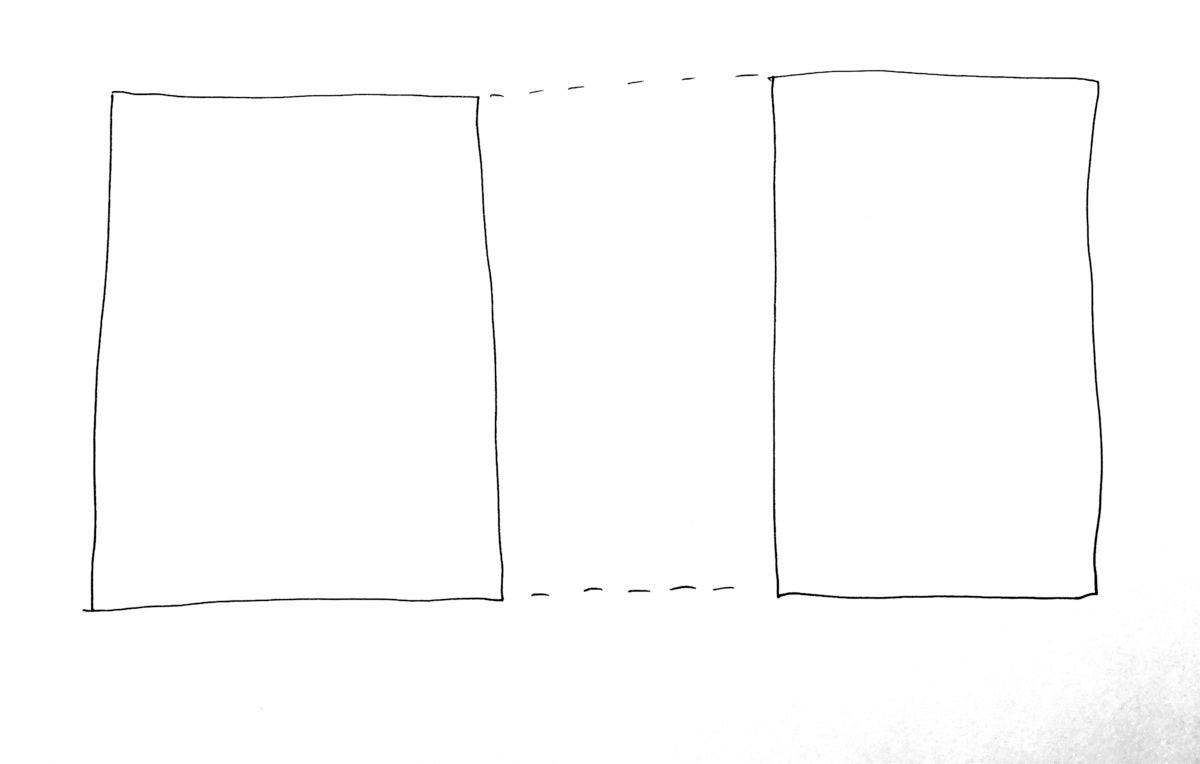

Reading Agee’s words, trying to imagine them, trying to remember if I’d seen something similar as a child in North Carolina, I’d drawn a picture in the margins like this:

Over a year after Agee, a friend used a term I didn’t recognize. He told me his parents were building a “dogtrot” in Texas. I asked him what he meant.

He elaborated. His description of the home—the breezeway, the divisions—struck a note in my memory. I recalled my shitty drawing. And then Agee’s stirring description—yoked boats, floated tanks, coffins. And then: I wanted to learn more about dogtrots.

Architectural forms are like words or plants: once you know their name and shape, they start showing up in unexpected places. I found descriptions of dogtrots in William Faulkner and Eudora Welty. I spotted a dogtrot when visiting a friend in New Orleans. With time, its odd design swelled in my imagination; its shape loomed large and numinous.

I went dogtrotting in June. Chance and time determined my itinerary. I had only five days and hoped to find dogtrots in almost as many states. I settled on four: North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia.

In writing about this trip, I wanted to talk about art. This is an art magazine. I wanted to describe the homes, their particular formal features, all that. But I also wanted to tell the stories of the people who’d left and preserved these architectural traces. I wanted to think about why they came to exist, why they spread through the South, why they remain—and why they’re rapidly vanishing.

Dogtrot, possum-trot, pigeon-trot, turkey-trot: terms that conjure a space the critters run through. Terms weirder but equally sonorous: saddlebag, dingle.

Talk to cultural geographers. Listen to architectural historians. You won’t get a unanimous answer as to how and where a bunch of backwoodsmen got

the idea of running a hallway—a breezeway—right through the middle of their homes. And you’ll hear that perhaps no other architectural structure incarnates the South as the dogtrot.

Architectural forms are like words or plants: once you know their name and shape, they start showing up in unexpected places.

The writer John Jeremiah Sullivan calls the dogtrot “a totemic form of southeastern architecture.”2 The photographer William Christenberry remembers it as “the architecture of my childhood.”3 The folklorist William Ferris sees “a mythic image in southern culture.”4 You can find dogtrots as far north as New Jersey, as far west as New Mexico. But there’s no doubt that where they took off, where they became naturalized as they nowhere else would, was in the Southern states: Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, the Carolinas, Alabama, Georgia. So ubiquitous were dogtrots in this last state that in 1827 a British visitor proclaimed:

Almost all these forest houses in the interior of the State of Georgia consists of two divisions, separated by a wide, open passage, which extends from the front to the back of the building… .This opening being generally ten or twelve feet wide, answers in that mild climate the purpose of a verandah, or sitting-room during the day.5

Today, you are not likely to encounter a single dogtrot in the interior of the State of Georgia, unless you go hunting for one. A historian at the University of Georgia assessed the status of the dogtrot in 2009. His findings were sobering: “the dogtrot house type is steadily disappearing from Georgia’s landscape.”6

Indeed, over the past fifty years, the songs of praise that have elevated the dogtrot to a Southern icon have been accompanied by an elegiac counterpoint. Here’s the libretto:

The log dogtrot is both quite rare and rapidly disappearing.

—National Park Service, 2014

Sadly…it continues to disappear from the

region’s landscapes.

—Geographer John Rehder, 2012

The dogtrot [is] a fast disappearing

architectural structure.

—Curator Judith Bonner, 2006

Dogtrot houses are disappearing.

—Art critic Benjamin Forgey, 1994

The dogtrot house [is] a vanishing species.

—Art historian Jean Sizemore, 1994

The dogtrot-style house…is quickly disappearing

from the scene.

—Regional planner Carol Collyar, 1973

There is a sense that the dogtrot, like so much so-called folk culture in the United States, is a creature on the verge of extinction.

Just how did the dogtrot first come to the South? That question stokes the flames of academic contention. For some scholars, it’s nice to see the structure as the spontaneous fruit of the enterprising Southern soul. To partisans of this camp, the dogtrot is a native growth of “the [warm] Tennessee valley,” whence its breezeways stretched to the neighboring lands of the Carolinas, Alabama, Georgia.7 Others—with the disappointing wisdom of the botanist who knows that most wisteria in the South is invasive, not the native stuff that enraptured Faulkner—insist on the dogtrot’s “Old World” origins. They are the bane of Southern romantics.

This baneful contingent itself splits in two. One half cries: The dogtrot is Germanic! The other half: It’s Finnish! Both hypotheses acknowledge a historical truth: only in Scandinavia and regions of the Alps can you find buildings that resemble this archetypal Southern home.

In the countryside of Salzburg, Austria, where the Eastern Alps rise, you can find “double-crib barns.” That is, two square cabins sharing a common roof, with a large space between. The middle part wasn’t for hanging out. It was more of a garage than a breeze way. You parked your wagon there. You threshed your grain. All the same, the overall structure recalls nothing so much as a dogtrot.

A group of Salzburgians immigrated to the American South in 1731, when Salzburg’s Catholic archbishop signed an edict to the effect of: Give up your Protestant ways or be banished. The Protestant Salzburgians were banished. In seeking safe haven, they appealed to a German-born Protestant of considerable means: George II, King of England. George had recently chartered a colony in the New World. He called it Georgia. George decided this colony, originally conceived as a place to send “miserable wretches,” was fit for the Salzburgians. In 1734, 150 of them arrived. They brought with them their Old World ways. This included names like “Ebenezer,” the town they founded. (At one point, it was Georgia’s state capital. Now it’s deserted.) Some scholars think this also included a prototype of the dogtrot.

The partisans for a Scandinavian origin dismiss this theory. The Salzburgian double-crib barn wasn’t a dwelling, they say, unlike the classic American dogtrot. It was a barn. Only in Scandinavia did people actually build dogtrot-esque houses. They might use half as a milkhouse or storage room, but they lived in the other.

The Swedes and Finns formed an early minority among European immigrants to America, founding in the Delaware Valley a short-lived “New Sweden,” which included modern-day Philadelphia; Wilmington, Delaware; and Swedesboro, New Jersey. Their colony kicked off in 1638 and came to an end in 1681, when William Penn got his charter for Pennsylvania. But the Finns and Swedes stuck around, kept farming, kept building churches and homes. There’s a Finnish dogtrot on the banks of the Delaware river that dates to 1698. That’s thirty years before the Salzburgians got to Georgia. That’s eighty years before dogtrots started showing up in “the [warm] Tennessee valley.” Scandinavia’s got a strong case.

But the reason I’ve dragged you through these historical weeds isn’t to take sides in scholarly disputes. It’s to remind us how strange and convoluted the forces are that propel something like the dogtrot into a symbol of the South. Like many icons of American aesthetics—jazz, cowboys, abstract expressionism—the dogtrot is ultimately a product of conflict, fusion, imperialism, dispersion. Perhaps more important than who brought its blueprints to this country is how it was subsequently taken up by Southerners of an enormous economic and ethnic range, who gave it the geographic spread and cultural poignancy it possesses today.

When James Agee and Walker Evans headed to Alabama for Fortune magazine in 1936, they found white tenant farmers living in dogtrots, sleeping seven to a room. At the Belle Meade plantation near Nashville, where today middle-class tourists go to wine tastings and admire a Greek-Revival mansion, enslaved people inhabited a dogtrot, as did free Blacks after them. John Ross, the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1828 to 1866, lived in

a dogtrot until 1838, when he was forcibly removed with the rest of his nation by the U.S. government; the house still stands in Rossville, Georgia.

The dogtrot flourished in the South for the same reasons as many of the region’s invasive species: it was preadapted to the hot humid clime.

It gave shade. Wind passed through. It was a good place to pass time in the summer. You could spend the day sewing in the breezeway and stay relatively cool. You could eat dinner there and avoid the overheated kitchen. In the evening, you and your friends could sing, dance, make music. If it was especially sultry, you might even sleep out on the breezeway. In 1937, one obscure Mississippi writer recollected witnessing this last use in his youth: “The house-wife placed a high-posted bedstead under this roof and hung thick homespun curtains around and over it, and this made a private and pleasant sleeping place for two of the boys.”8

People have wondered how well the breezeway actually works. In 1998, two researchers at Mississippi State’s School of Architecture decided to subject the dogtrot’s fabled cooling properties to empirical scrutiny. They went to an 1840 dogtrot in French Camp, Mississippi. In tow were anemometers, pendular wind measuring devices, things like that. They measured the speed and direction of wind around the dogtrot and through its breezeway. Later, they built a scale model of the house. They blew air and smoke at it and watched. Their conclusion was strong: “Our investigation shows the dog trot’s ventilation system to be successful.”9

II.

So what he found was not only what he was hunting for but what he had expected: a weathered paintless dog-trot cabin.

—William Faulkner, The Mansion (1959)

The first dogtrot on the docket was in Concord, North Carolina. I departed from Durham, arriving by way of roads that’d been repaired so many times the tar patches braided together in an extravagant vine.

The Spears House is set some eighty yards back from Morrison Road. There’s a stand of oaks on its left; a big old ash shades the right. There’s a lazy heat to the land. Birds peep. The leaves of the white oaks swish. Somewhere far off a lawn mower drones. When this dogtrot was first constructed, by a second-generation Scottish immigrant named William Wallace Spears, one would have entered the house by way of the breezeway. But the structure now bears a blight common to many remaining dogtrots in the South. Its breezeway is filled in. Where the breezeway had been there is now wood siding and an air-conditioning unit.

I knock on a door that’s been built into one side. A dog within goes nuts.

“What?!” A woman shouts behind the door, above the barking, after I ask if I can look around the property and take some photos.

“How long will it take you?!” “ 30 minutes?!”

“Can you make it 15?!”

“Yeah!”

“You’re awesome!”

“Thanks!”

I dash about, take some photos, scribble some notes, and check my watch. My fifteen minutes are almost up. The dog’s almost ready to hurtle out the erstwhile dogtrot. I stand for a second more, looking at the filled-in breezeway, listening to the white oaks, taking it all in, and then a sound makes me jump. With a snap and a groan the AC’s switched on.

There is a story passed on by rueful environmentalists. It appeals to Southern romantics. It goes like this: AC killed the dogtrot. When it arrived, people boarded up their breezeways. People stopped building dogtrots.

This story is tributary of a grander narrative, about how the landscape of the South was transformed over the course of the twentieth century. Joan Didion told a version of this tale when she traveled through Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana in the summer of 1970: “Southern houses and buildings once had space and windows and deep porches. This was perhaps the most beautiful and comfortable ordinary architecture in the United States, but it is no longer built, because of air-conditioning.”10

The term “air-conditioning” was born in the South. It was coined by a North Carolinian engineer in 1906, at the Kenilworth Inn in Asheville. Standing before the American Cotton Manufacturers Association, Stuart W. Cramer touted the industrial applications of the nascent technology. His idea wasn’t to keep the people cool. It was to keep the cotton cool in mills:

Cotton contains about 8 per cent natural moisture, a part of which is lost in the process of manu-facture. . . . This source of loss is often ignored, but included under the head of “invisible waste.” The installation of an efficient system of humidification, however, will reduce this item of invisible waste easily from 1 per cent. to 3 per cent.11

Thus the major innovations in AC technology took place in the South at the beginning of the century, developed to maximally preserve the South’s traditional, blood-stained cash crops: cotton and tobacco.

Not until after World War II did domestic air conditioning make financial sense. The number of Southerners with AC was over double the national average in 1955. By 1970, two-thirds of Southern homes had it.

This changed architecture, and with it, society. Architects stopped adapting their structures to the region’s climate and started adapting them to the AC. As early as 1945, the industrialist Henry J. Kaiser had envisioned what would become the model for almost all American housing: “complete communities of mass-produced air-conditioned homes.”12 In 1949, the magazine Better Homes & Gardens announced to the world: “Your New Home Can Be Designed for Air Conditioning.” That is, you could get rid of the big porches, the high ceilings, the raised floors, the tall windows, the transoms, all the time-tested techniques known as “passive ventilation.”

The complement to Didion’s aesthetic lament is a social one: When porches and breezeways fell out of fashion, the South lost important communal spaces. I spoke earlier of nostalgia, but this fact is observed even by Southerners who are under no gauzy illusions. The historian Trudier Harris came of age in mid-century Alabama, where her father, a successful Black farmer, was jailed for a year on the mere accusation that he’d stolen a single bale of cotton. Her writing is not prone to wistfulness. Yet where architecture is concerned, she clearly believes something was lost:

Until the mid-20th century and prior to the wide-spread use of air-conditioning, families gathered on front porches in the early evening to wait until their hot houses cooled off. The waiting process provided time for sharing the day’s events and for storytelling. Extended family members and neighbors were often incorporated into these communal gatherings.13

III.

After Concord I drove further west, into the Appalachians, to Sandy Mush, North Carolina.

I was looking for the house of Ervin Boyd, a formerly enslaved man who’d built a dogtrot after gaining his freedom. Unlike the dogtrot at Concord, this one had not been graced by a record in the United States Registry of Historic Places, making it considerably harder to find. Even Google was of only limited help. I resorted to trial and error and a few different maps.

The life of Ervin Boyd is as obscure as his home. Few traces of him exist—some census records, a will, a codicil. What we do know is that shortly after the Civil War, Ervin bought 50 acres in Sandy Mush. By at least 1870, eight years after the Emancipation Proclamation, he lived there with his wife and ten children, and his mother lived nearby. The land he purchased was flat and fertile. Sandy Mush creek ran northeast to southwest. Mountains rose on all sides. Here Ervin did what those without access to mill-sawed timber did. He cut his own logs. He shaped them by hand with axe and adze. He worked carefully. In a way, he worked with more skill than the well-to-do farmer who’d built the dogtrot in Concord had. Instead of fitting his logs together with rudimentary square-corner notches, Ervin opted for half dovetails. These notches helped the dogtrot stand, unrestored, unaided, for 150 years.

The day I walked through Sandy Mush Valley, the Ervin Boyd dogtrot was not standing. Some weather-worn logs lay in the dirt, beside the foundation stones of the fireplace. Blue tarps were spread over the former perimeter. I lifted the tarp and found bugs.

Leaving the property, I drove further south, with the intention of stopping at the most approachable looking property and asking: What happened to the Boyd house?

A couple was working in the yard. I pulled up. “ Boyd house?”

“ What?”

“ Dogtrot?”

“ What?”

“ Old cabin, used to be about a mile northeast?”

They didn’t know. But the folks down at the community center probably would. There are signs for it back where I came.

There’s two community centers in Sandy Mush. Each has a drastically different function. They also differ with regard to the tenacity of their signage. At the beginning of Boyd Cove Road, just north of where Ervin’s house should have been, I spotted a sign for the Long Branch Center. This seemed promising. It was hand-painted, blue text against green, inviting. I drove a few minutes before the second sign announced:

Long Branch Center

1/2 Mile

I was on the right track. The car climbed. The angle of the road augmented. The third sign appeared. Same paint, same font:

Long Branch

Environmental Education Center

1/4 Mile

Environmental education center? The road rose out of the valley, climbed the mountainside, bordered no longer by fields but clotted with trees. The gentle slope became a forty-five-degree pitch.

The Long Branch Center’s signs are spaced with ingenuity. Where the road devolves into steeply inclined mud you get a penultimate prod:

You’re Almost There

And where a driver without a Chevy Silverado 1500 ZR2 might doubt his ability not to slide ass-backwards down the mountain, a cheerful placard pops up:

Keep Going

Keep going and a grassy landing, travel trailer, and wooden cabin greet you. This last structure is labeled “Community Center.” I walked in.

A gangly young man looked up from his coffee. I told him some people below said I might learn about the fate of the Ervin Boyd cabin up here.

“I’m just a volunteer,” he said. He was from South Carolina. Not local. “That sounds like something Paul would know about.” Paul was up there, past the trout pond, in the house on the right.

The path to Paul is gnarly. When I reached the porch, I spent five minutes marveling at the traces of projects completed, abandoned, nascent, and

in-progress—a real ratatouille. There were paint buckets and plastic planters. There were shovels, shears, rusted wheelbarrows and busted umbrellas. There were American flags, black bear flags, Tibetan prayer flags, psychedelic peace-sign flags, flags of the planet earth. Rubber boots, plant food, Christmas lights, tie-die blankets, eagle feathers.

I knocked on the door. A gentle bear of a man appeared. I told him what I was about. “I heard you might know something about the Ervin Boyd home.”

“Let’s take a seat.” Paul flipped over two paint buckets and we got to talking.

Permit me a detour. I need to tell you about Paul now. He is one of those guys.

Paul was at UC Berkeley in the ‘60s, in the height its political fervor, where he studied anthropology, philosophy, ecology. He spent 1968 abroad, at the Sorbonne in Paris. That was the year the student body built barricades, occupied campus, and chucked paving stones at cops in protest of De Gaulle’s France. After he graduated, Paul and his wife, Pat, drove a hippie-fied bus through the American South, sleeping in a teepee they kept tied on top. When they got to Buncombe County, North Carolina they stayed.

In recounting these things, Paul stood and took me around the center, pointing out the passive solar design of the buildings, showing off the local flora. When he identifies a plant, he gives its Linnaean, common, and indigenous names. Except when he shows you poison ivy. He calls it “Sister Ivy.”

“Don’t touch that,” he said, when I almost brushed against Her. Then, in cheery defiance of his own prohibition, he plucked a handful of the leaves and chewed, an insouciant ruminant. “I’m immune. I learned from the Native Americans. You eat a little bit of the young plant at the beginning of spring, when the leaves are still red.” He wanted me to try but, alas, it was summer. We couldn’t find a young enough plant.

At this point it’d become clear that I was at the wrong community center. Paul did not know about the Ervin Boyd house. But he knew about dogtrots.

“It’s sort of like a log cabin?”

“Exactly.”

“And is there a walkway between the two? That was for ventilation in the summertime?”

“Right.”

He was immediately enthused. “It’s an interesting way, especially down east, to overcome heat in the summer months, to have that ventilation.” Paul is obsessed with passive solar design—buildings that maximize sunlight in the winter and minimize it in the summer. He found the dogtrot’s “passive cooling system” inspiring, antidotal. “When we had the misfortune of discovering fossil fuels, we got separated from nature.”

As I was about to leave, Pat arrived.

“The Ervin Boyd house?” she said, after Paul told her why I’d come. “Weren’t some people at the Preservation Society working on that?”

I would learn that the Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County had labeled and disassembled each log of the Ervin Boyd dogtrot last summer. Its deconstructed parts now lie in storage. The society’s intention is to raise enough money to rebuild and preserve the cabin, bringing greater exposure to Ervin Boyd’s story.

There’s often something sad about transporting an artwork, or sculpture, or home from its original context to the pseudo-perpetuity of a museum or monument. There’s something sadder about a building like Ervin Boyd’s decaying in obscurity, unknown by even its neighbors. The Preservation Society has at least maintained the possibility of Ervin Boyd’s life—and architecture—extending to a broader public, potentially transforming that public’s perception of what went on in this part of the country. For one thing, many people don’t know that slavery spread to Appalachia; often this fact is forgotten by those who live in the region. Most people I talked to in Sandy Mush had no idea. For another, the dogtrot’s a dying breed. Who knows how many cabins like Boyd’s have been bulldozed into oblivion? Who knows how many are rotting unseen? The dogtrots can use some help. Their loss is more than that of how our precursors lived. Their loss is that of a tool for imagining the future.

There is the crushing weight of history—and then there is its lightness, its air, its wings. There is history that seems to condemn and condition us, to determine and narrow the field of human possibility. And then there is history that tells us what now seems unthinkable was once immanent, if not actual. Maybe the dogtrot is part of this second history.

Who knows how many are rotting unseen? The dogtrots can use some help. Their loss is more than that of how our precursors lived. Their loss is that of a tool for imagining the future.

It is not that so rudimentary a feature as the dogtrot’s breezeway contains the secret for sustainable design. It is not that AC is a superfluous luxury which we, like our hardier predecessors, should do entirely without. The forests are burning. The heatwaves are becoming more common, more lethal. Last summer, heat-related deaths increased from 0 to 119 in Oregon and 2 to 145 in Washington. AC is, will be, a necessity for many.

But like the passive solar houses Paul so proudly espoused, like the cheap tin rooves that reflect the Southern sun, the dogtrot is a reminder that there are eminently simple solutions to accomplish what we currently do by absurdly wasteful means. To preserve this endangered architectural species, then, is to preserve a potent line of thought.

At least, this is the utopian tint the Long Branch Environmental Center lent my thoughts as I headed to Sewanee, Tennessee, the next morning.

IV.

Under a light rain I reached the house in Sewanee. It was set on a bluff looking out over coves of the Cumberland Plateau. Near the edge of the bluff, before a faint mist, a white-haired woman was gardening.

“Hello!” I called.

The woman looked up from her work, wiped her hands against her overalls, and gave a smile that betrayed no surprise—nearly a look of recognition. Yes, she was Lee Stapleton.

She was patient as I described what I was searching for. By this point I’d decided to stop using the word “dogtrot” when first meeting folks. There was no need for this strategy with Lee.

“You mean the dogtrot,” she said when I’d finished.

“Exactly.”

Lee knew the term well. She and her husband, Archie, had built the dogtrot I sought. That is, using a process similar to that of the Preservation Society with the Ervin Boyd house, Lee and Archie had individually labeled the logs of two local cabins that were going to be demolished. Then they rebuilt them on part of their land, deciding to join them in a single structure by means of a breezeway. Thus a dogtrot came to be. Today, a grandson lives there. In the past, they rented it to students, after living there themselves.

Before she could point me its way, the light rain became a deluge. She invited me in her home to wait it out. We would have tea.

We stepped inside. I looked around as Lee closed the windows blown open by the wind. She and Archie had built this house too, with the help of some friends. “He didn’t want to try anything too complicated,” she said. “He bought a book. How to Build a Two-Car Garage.”

Before making tea, Lee brought out a sepia photo. A family of farmers stands before a cabin. The kids are barefoot and cheery. The adults grave. “That was the Gudger family,” she explained. In the nineteenth century, the Gudgers built one of the cabins that’d make its way into the dogtrot. The man who sold the Stapletons their land, Lawton Gudger, grew up there and continued to live nearby.

Lee served tea ceremoniously: on a silver tray, with gilded cups and saucers, a sugar bowl and cream pitcher, a tall porcelain teapot. I found it charming, but it gave me pause. This kind of elegant formality can be a suspicious thing in the South, especially when thirty minutes ago you were driving past confederate flags and Trump 2024 signs. I started to wonder. Had I chanced upon a descendant of the Southern aristocracy? Would Lee’s sweetness take a dark turn? I bracketed my worry as Lee poured the tea.

The wonderful thing, the humbling thing about those who are rich in years: they do not need to “stay on topic.” Maybe you want to discuss X. Maybe you want to discuss Y. They will do so, but they’ll interweave X or Y into the fabric of a full life. They will widen the horizon of relevance.

I’m not saying Lee was not self-possessed. At eighty-seven, she was sharper than I am. But there were things I wanted to talk about right away: Where’d you get the idea of building a dogtrot? Did you see them where you grew up, or around Sewanee? Do you know to when the cabins originally date? And who the hell was that Thom guy, with his branches and blessings? Then there were things Lee seemed to want to talk about, like going to the Cuban markets in Ybor City, Florida, as a little girl with her grandfather. Or conducting anthropological research in the Philippines. Or attending medical school in Grenada when she was in her fifties.

In her unfurling of this almost impossibly rich life, little details made clear that a joyful sense of social responsibility had oriented it. I mean, it seemed like she cared about people. For instance, after graduating from medical school at the age of sixty-one, Lee decided to work at the Chattanooga Veterans Affairs Clinic.

“They asked me, ‘Why are you here? Are you a veteran?’ And I said, ‘No, I’m a pacifist!’ They said, ‘What’s that?’”

I asked Lee where this orientation had come from. She smiled wickedly. “I’m kinda a commie.” She thought some more. “I think my dad was a socialist. But you couldn’t be a socialist then. Or they’d get you.” Instead, he was a supporter of FDR and his New Deal policies. Lee recollected seeing FDR with her dad once, in Washington, D.C. He’d waved to them from his car. “I was in love with him,” she said.

This led to some gushing on both our parts about the Works Progress Administration, the New Deal agency that fostered some of the most poignant art this country has produced—Ruth Crawford Seeger’s arrangements of American folk music, Chester Don Powell’s National Park Service posters, Jacob Lawrence’s The Migration Series. That agency also brought about some of the most loving descriptions of dogtrots on record. When members of the Federal Writers’ Project scattered about the states in search of insufficiently appraised American culture, they were consistently taken with “dogtrot houses with cool open hallways and clean scrubbed galleries,” as The WPA Guide to the Magnolia State puts it.

In my ecological zeal I have neglected a key reason for the dogtrot’s popularity, other than its cooling powers. Namely, the design easily allows one to expand a small home into a larger one. If you needed to build a home fast you could start with a single small cabin. Once you had the time and resources to build more, you could connect a second space by means of a breezeway. Voilà, a dogtrot.

The Stapleton’s dogtrot openly proclaims that it is two different cabins sutured together at will. The right part has one story and a hip roof. The left part has two stories and a gable. The right is put together with square notches. The left has half dovetails—fat teeth biting into the wood above them. Between the two the passage lies, dark and streaked with cool air.

Far after my visit I wanted to know what it’d been like to actually inhabit that space. I talked with a writer who’d lived there years back, the one who first told me about the home. He described how it felt to spend time in the breezeway, “this middle ground between outside and inside.” He described how air passed through, in a constant, mild flow. “I can still kind of feel that in my skin, you know?” I’d just come to know.

V.

The construction of the Eversole dogtrot in Krypton, Kentucky, was also a piecemeal affair. Though it’s not easy to tell. There are two parallel chimneys, two sides of equal width and length. At a quick glance your eye tells you: Ah, symmetry, balance, the Platonic ideal of the dogtrot. You peer and try to spot the differences. You peer and you peer, and then you get dizzy.

I’d caved the night before and booked a room at the Smoke House Lodge in Sewanee. Having slept in my car the first night, my tent the second, and with the longest stretch of the trip yet before me, I wanted a proper sleep. That’s how I’d justified it to myself, this spending of $62.23 with no expense account to bill it to, with those soothing words: A proper sleep. So I thought. Feeling joyous after my encounter with Lee, I called a close friend and babbled to her about dogtrots and historical preservation late into the night, drinking whiskey the while. There was no proper sleep.

So when I got to the Eversole dogtrot, my wits were not altogether about me. I gathered them up enough to notice that depending on the section you’re looking at, you’ll see v-notches, half dovetails, square notches, each revealing a different stage of the building process.

Another part of the dizzying asymmetry—this one unwilled by its builders—are the bullet holes. A news-letter published by the local Civil War reenactment committee tells it like it is: “As you walk around the porches and view the large holes made by the larger caliber rifle round, the Civil War is no longer idle statistics about far off places. The civil War is real, and close to home, here on the North fork in Perry County.”14

Here on the North Fork in Perry County, Jacob Eversole built a one-room cabin, in 1789. Over the course of ten years, Jacob transformed it into a

two-story dogtrot, where many an Eversole would live. It was raided twice by confederates. The first time they damaged only the dogtrot. The second time, they shot to death two of Jacob’s grandsons who’d fought for the Union.

The dwelling stayed in the Eversole family for a remarkably long time, until 1996. Then Denny Ray Noble, a local politician and farmer, bought it from one of Jacob’s descendants. I can’t tell you much about the Nobles. They are a laconic and industrious bunch. After I arrived at their property, three generations of them passed before my eyes in the span of minutes.

DENNY RAY NOBLE pulls up.

WRITER (Approaching tractor)

Hey. I’m the guy who called last week. I’m working on an article about architecture in the South. Do you mind if I have a look around the Eversole cabin?

DENNY RAY (Impassive)

That’d be alright.

DENNY RAY drives away hauling hay.

DENNY RAY JR. pulls up.

WRITER (Approaching truck)

Hi. I just talked with your dad.

DENNY RAY JR. starts attaching fishing boat to hitch.

WRITER (Cont’d)

I’m gonna have a look around the Eversole house for this article I’m writing.

DENNY RAY JR. (Impassive)

I’m fixin a’go fishin.

DENNY RAY JR. drives away hauling boat.

WRITER pulls out camera, approaches dogtrot.

DOG IN DOGTROT (Indignant)

Guf! Gufguf! Guf! Guf!

DALTON NOBLE pulls up, gets out of truck.

DALTON (Impassive)

Did she eat ya up?

WRITER (Approaching truck)

Yup. She’s vicious.

DOG OUT OF DOGTROT

Guf! Guf!

DALTON

That’s Dixie.

WRITER

I just met your dad and grandpa. I’m here working

on a magazine article. Do you guys ever use the cabin for anything?

DALTON

Nah. You can go in there.

DALTON NOBLE retrieves something from garage, returns to truck, drives away hauling ass.

DIXIE (Back in dogtrot.)

Guf! Gufguf!

Dixie eventually stopped barking and lay down. She let me take some pictures and walk in the breezeway. It was hot that day, my head was unhappy, and I did not want to leave. I rested a moment, thinking about how odd it was, this dogtrotting. One minute you’re talking to a self-proclaimed commie, the next you’re upsetting a dog named Dixie.

VI.

My dogtrotting ended in Forest, Virginia, a thousand miles from where I’d begun. I went down from the Appalachians to the foothills, to the former site of the Ivy Cliff plantation.

I’d learned of a dogtrot here through the University of Maryland’s Virginia Slave Housing Project, which began in 2007. One of its founders, Professor Dennis Pogue, has stated their mission thus: “Our goal is to gather information on these buildings before they are lost… . We hoped that by paying attention to these buildings, we’d get other people to pay attention to them too.”15 As far as I can tell, it’s one of the only statewide programs devoted exclusively to documenting the dwellings of enslaved people. There is no equivalent in North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, or Mississippi, though the state of Alabama started a similar initiative in 2020.

The plantation began when this land was acquired around 1755 by the Brown family, who’d come down from the Northeast. They used the labor of enslaved people to grow tobacco and grains. Ivy Cliff today comprises seventeen acres, but by 1832 the Browns owned at least 732. At that time one of their members, John Thompson Brown, had become a prominent politician. If you would like to know what kind of man he was, you can read his speeches on slavery at the Virginia House of Delegates. They are a paradigm of bad faith—a sophist wielding statistics to conceal a moral abyss.

Like an organism, it has adapted to the conditions of its landscape. It is an image of this landscape, a cipher of the South. Like any organism, like any cipher, its essence is elusive. You approach. It retreats. You define. It extends, expands, explodes into the diversity of its species.

Here enslaved women and men lived in a dogtrot. This was common: enslaved people inhabited dogtrots in Arkansas and Tennessee, Alabama and Mississippi. The reason is repugnant. The dogtrot provided a convenient way to house multiple groups of enslaved men and women without individual structures. Whereas the dogtrots of freemen often had one designated half for sleeping, one for cooking or working, those of the enslaved did not. They were cramped, for both halves had bedrooms. Although not the case at Ivy Cliff, this division was sometimes expressed architecturally. The dogtrots of freemen set their doors under the breezeway—a material sign that both halves belonged to one family. Those of the enslaved often opened directly to the outside—a material sign that the two halves of the building housed separate groups. (With emancipation, many former slaves built dogtrots for themselves, then occupying the building’s entirety.)

If this means the breezeways built on plantations were not intended for the various functions we today associate with the dogtrot, it doesn’t mean they

went unused. We know enslaved men and women appropriated what space they could. Often this was a porch. There enslaved people might dance, sing, tell stories, and worship. In a breezeway, in a home set below a slope, they might have done so at Ivy Cliff.

The dogtrot here was built in two stages, between 1810 and 1830. Of at least seven slave cabins on the property, it is the only one that still stands. This gives you a sense of what is at stake, of why the Virginia Slave Housing Project exists. The number of preserved slave dwellings in the U.S. is miniscule. In some places, they are all but erased. Before emancipation, thousands of slaves lived in Delaware. One slave dwelling remains in that state. In 1860, there were over a thousand slaves in Austin. One slave dwelling remains in that city. In “Little Dixie,” a historic county in Missouri, there were an estimated 13,300 slave dwellings before the Civil War. Today, there are 130.

Speaking broadly but truly, slave dwellings weren’t destroyed by Black people who found their sight painful. They were destroyed by white people who no longer found them useful. This has left us, throughout the South, with “charming federalist homes,” “stately neoclassical manors,” and “grand Georgian estates,” rather than vestiges of plantation slavery. This has buried the past.

In May 2022, one of this country’s oldest historic preservation groups, Preservation Virginia, listed the Ivy Cliff dogtrot as one of “Virginia’s Most Endangered Places.” My visit fell less than a month later. It bore this label out.

Virginia creeper fringes the home’s front. In the back, invasive empress trees push their roots beneath foundation stones. One of the fireplaces slouches out. The back-left wall has collapsed. Less than a hundred yards west, the “big house” stands, restored in the last decade by now-gone proprietors.

Plantation property should have been owned by those who worked it. If our country had carried out reparations, such land would have been divided in 1865 among the enslaved, if not their descendants today.

As things currently stand, the latest owners of Ivy Cliff are a retired couple who recently moved up from Florida. They at least give a damn about the dogtrot’s sorry state. When I arrived, Mike Taylor directed me to Sophie Taylor. Sophie took me around. She had spent time in the archives of Bedford County, and of William & Mary, learning about the property. She had spoken with local historians and preservationists. She had heard the cries of endangerment. “We’re in the process of final paperwork on a nonprofit,” she told me. “So hopefully we can raise the funds to restore [the dogtrot] and open it up to local school groups.”

There are no firsthand accounts by the enslaved people who lived in the dogtrot at Ivy Cliff. The closest we can come to them are records of other former slaves. It took the worst economic downturn in U.S. history for these records to be made; for what we have, in large part, is the result of the Federal Writers’ Project’s Slave Narratives, oral histories conducted from 1936 to 1938.

They should not be read uncritically. Almost all the interviewers are white, and they were often transcribed in an insolently exaggerated dialect. Some of the interviewees contended with the very premise of the project. (“I aint gwine give you no more, gal,” said Della Harris of Petersburg, Virginia, after her request for compensation during a 1937 interview with Susie Byrd went unheeded.16) Despite these limitations, many of the voices come to us strong and frank. Here is Fannie Fulcher on dogtrots in Georgia:

Houses wus built in rows, one on dat side, one on dis side—open space in de middle. . . . We cook on de fireplace in de house. We used to have pots hanging right up in de chimbley. When dere wus lots of chillun it wus crowded. But sometimes dey took some of ‘em to de house for house girls. Some slep’ on de flo’ and some on de bed.17

Later in the interview, Fulcher tells how, “We used to have big parties sometime. No white folks. . . . I ‘member dey have a fiddle. I had a cousin who played fer frolics.”18 Accounts of this sort— of the party, of the frolicking—could easily be used to whitewash slavery, and interviewers sometimes asked leading questions. (One from an interview in Georgia: “Do you remember anything about the good times or weddings on the plantation?”19). But Fannie Fulcher describes the squalid living conditions. At another point, she speaks of physical abuse. Her account of what sociality was possible stands beside these facts—not, I think, as a response to her interviewers’ manipulation, but as an assertion of a communal life under, and in spite of, extreme duress.

I mentioned what a small fraction of slave dwellings remains. The same is true of “slave narratives.” There were nearly four million enslaved people on the eve of emancipation. The extant number of firsthand accounts of slavery is just over six thousand. Almost 40 percent of these are from the Federal Writers’ Project. We cannot recover more. Though we can preserve and promote what materials—both stories and dwellings—abide. We can recognize what invaluable fruit they bear. Something sinister happens to the soul of the country when it lets this work fade and fall out of sight.

VII.

The dogtrot holds a hall, through which the weather passes. Two swelling wings, and a shadowed maw.

Like an organism, it has adapted to the conditions of its landscape. It is an image of this landscape, a cipher of the South. Like any organism, like any cipher, its essence is elusive. You approach. It retreats. You define. It extends, expands, explodes into the diversity of its species.

Any yet its species is there, somehow an entity distinct. This base identity. This fundamental shape: housing, collapsing, extending.

[1] James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (New York: Library of America, 2005), 130.

[2] John Jeremiah Sullivan, “Southern Exposures,” Bookforum 20, no. 2 (summer 2013).

[3] Ben Sloat, “An Interview with William Christenberry,”Big, Red & Shiny, December 1, 2008, http://bigredandshiny.org/5183/aninterview-with-william-christenberry/.

[4] William Ferris, “The Dogtrot,” Southern Quarterly 25, no. 1 (Fall 1986): 72.

[5] Basil Hall, Travels in North America in the Years 1827 and 1828, vol. 3 (Edinburgh: Robert Cadell, 1830), 271.

[6] Sheldon Owens, “The Dogtrot House Type in Georgia: A History and Evolution,” (MHP diss., University of Georgia, 2009), 57.

[7] Henry Glassie, Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1968), 98.

[8] Kincannon Lowery, Mississippi: A Historical Reader (Nashville: Marshall & Bruce, 1937), 70.

[9] Aaron Gentry and Sze Min Lam, “Dog Trot: A Vernacular Response,” (manuscript, Mississippi State University, 1998), 10.

[10] Joan Didion, South and West (New York: Vintage, 2018), 69.

[11] Stuart W. Cramer, “Recent Development in Air Conditioning,” Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Cotton Manufacturers Association (Charlotte: Queen City Printing Co., 1906), 184.

[12] Raymond Arsenault, “The Air Conditioner and Southern Culture,” The Journal of Southern History 50, no. 4 (Nov., 1984): 597–628.

[13] Trudier Harris, “Porch Sitting,” The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, vol. 14 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, Press, 2009), 337.

[14] Paul Taulbee, “The Eversole Cabin Battles,” The Battle of Leatherwood Newsletter (October 2009), 23.

[15] Maggie Haslam, “Out of the Shadows,” University of Maryland School of Architecture, September 17, 2020. https://arch.umd.edu/news-events/out-shadows.

[16] “Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 17, Virginia, Berry-Wilson” (unpublished manuscript, 1941), PDF file, 25. https://www.loc.gov/item/mesn170/.

[17] “Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 4, Georgia, Part 1, Adams-Furr,” unpublished manuscript, 1941, PDF file, 311–12. https://www.loc.gov/item/mesn044/.

[18] Replace with: “Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 4,” 336.

[19] Replace with: “Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 4,” 224.