Movement: The Legacy of Kineticism at the Dallas Museum of Art invites viewers to see, touch, and interact with artworks spanning the twentieth century to the present. Exploring the relationship between art, the senses, and physical embodiment, the exhibition focuses on three notable art movements and their afterlives: geometric abstraction, Kineticism, and Op Art. Taking root in Europe and Russia, these formal experimentations challenged orthodox perspectives of what art could be. Artists turned inward, encouraging viewer participation through visual perception and bodily engagement rather than precise similitude.

Movement traces these distinct, yet overlapping, conceptual approaches to art-making with keen attention to medium specificity, transnationality, and artistic exchange. Drawing from the museum’s permanent collection, the show features eighty works spanning a wide array of media by artists from diverse regions around the world.

The immersive installation Vagalume (Firefly) by Brazilian artist Valeska Soares opens the exhibition. Affixed to bright overhead light structures, hanging metal chains fill the perimeter of the gallery’s entrance, gently bumping viewers’ bodies as they make their way through the space. Visitors are encouraged to activate the installation by pulling on the chains, turning the lights on and off. The flickering of these lights within the sensorial landscape allows viewers to connect with their bodies and the environment.

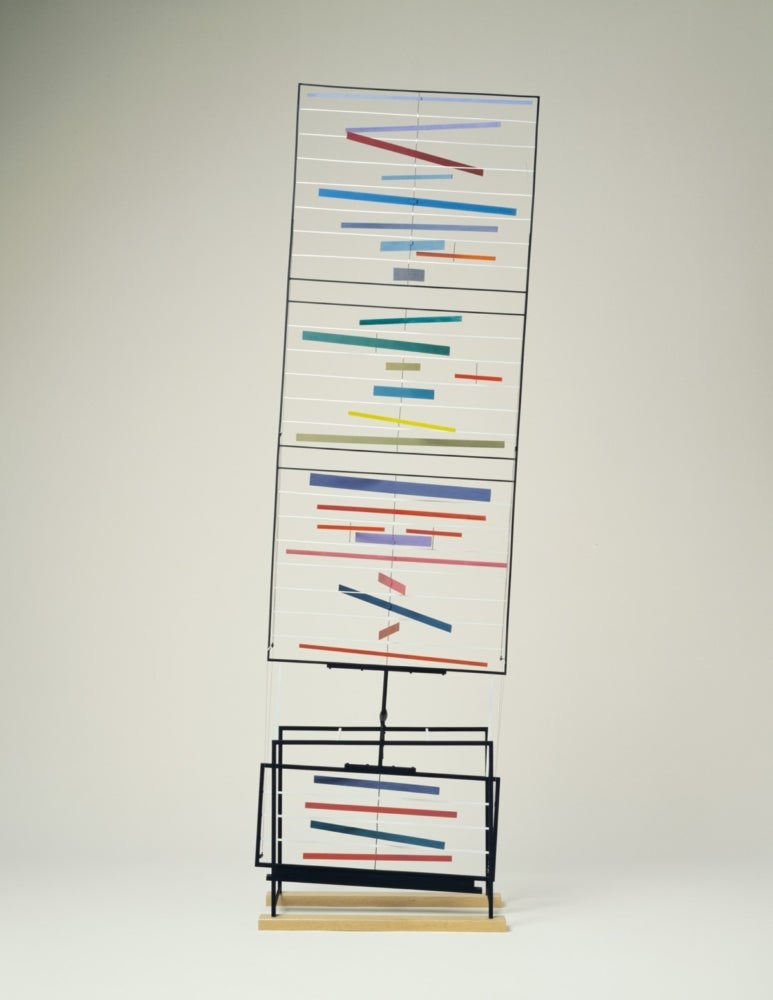

After passing through Soares’ Vagalume, viewers encounter another interactive object: U.S. midwestern artist George Rickey’s kinetic sculpture, U.N. II. Named after the United Nations building in New York, U.N. II alludes to the relationship between humans, the built environment, and machines. Relying on the kinetic force of wind, the piece is activated by the viewer’s movement. Colorful steel stripes, partially affixed to a black stainless-steel frame, gently sway from the airflow produced by viewers as they walk past this sculpture.

Active during the second half of the twentieth century, Rickey is known for his kinetic sculptures that combine principles of geometry with engineering, likely informed by his experience working with aircraft during World War II. His interest in both subjects illustrates a significant aspect of Kineticism: the incorporation of mechanized and geometric parts into artwork to evoke movement. Uniting geometry, engineering, and viewer participation, U.N. II serves as a strong and productive sightline, inaugurating the exhibition’s main themes.

Situated just past Rickey’s U.N. II sculpture is a small gallery titled “Before Kineticism: Utopia and Utility in the Avant-Garde.” As the name suggests, this gallery maps the precursors to Kineticism, starting with the 1910s art movement, Suprematism. Spearheaded by Russian artist Kazimir Malevich, Suprematism is characterized by geometric forms that float in white empty backgrounds and is considered one of the earliest forays into abstract art. Visualizing these principles are Malevich’s iconic illustrations of a black square and black circle for the art journal, From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: A New Realism in Painting. The artist’s experimentations with these simplified forms codified his larger engagement with Suprematist visual techniques.

A significant feature of this gallery is its representation of Latin American artists: Marco Maggi, Carmelo Arden Quin, and Alejandro Otero among others. Beginning in the 1940s, Latin American artists started adopting European avant-garde styles into their regional artistic practices. Uruguay was a notable epicenter for these experimentations with artists such as Joaquín Torres-García, known for incorporating Indigenous symbols into a geometric grid. The work of Torres-García’s student, Rhod Rothfuss, is featured in the gallery. Rothfuss took up a particular offshoot or formulation of Constructivism: Concretism. Like its predecessor, Concretism focused on geometry with greater acumen given to mathematical precision, as illustrated in Rothfuss’s Untitled. Breaking away from the conventional square compositional frame, Rothfuss delineates the pictorial boundary with different geometric forms, executed with remarkable precision.

Outside this gallery, the rest of the exhibition explores diverse artworks framed as the “legacies” of these art movements, namely Kineticism, Op Art, and works engaging with geometric abstraction. The exhibition explores an interesting relationship with artists who have spent significant time in Texas, framing these relations as “Texas Connections.” Artist Kazuya Sakai is included in this category. Born in Buenos Aires to Japanese immigrants, Sakai settled in Dallas during the later years of his life where he taught at the University of Texas at Dallas. His composition, Integrales II (Edgard Varèse), presents a stunning example of the dynamic interplay between geometric forms and colors.

Movement also includes works from a key development within the Kinetic art movement: jewelry. During the 1960s, designers from East Europe and Italy began experimenting with the potentiality of jewelry to serve as mechanical wearable parts. Incorporating geometric forms into their designs, these artists created necklaces, rings, and brooches that moved when worn. Visualizing these themes, this portion of the exhibition displays jewelry from artists such as Vratislav Novák, Anton Cepka, and Frank Bauer. These artworks are divided into two distinct sections. The first contains a display case of various types of jewelry. Noteworthy among these represented items is Italian artist Francesco Pavan’s brooch, Lamellar Cone, Homage to Raphael Soto. Dedicated to the Venezuelan Op and Kinetic artist, Rafael Soto, Pavan’s brooch mimics the artist’s optical experiments of perception and form. The piece is composed of thin golden strips arranged in a grid-like manner. Jutting out from this matrix is a sculptural three-dimensional relief of a cylindrical cone.

The second portion of this space features active mechanical jewelry parts. Multiple video monitors, displayed onto the gallery walls, play clips of the jewelry pieces in motion. Geometric parts of rings and brooches rapidly spin with awe-inspiring velocity and speed.

Across from these wearable jewelry works are the sculptural configurations of Brazilian Neo-Concrete artists Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica. Breaking from the austerity of Concretism, the Neo-Concrete artists of Brazil focused on the phenomenological or sensorial aspects of geometric forms in ways that fostered viewer engagement and participation. Sculptures such as Oiticica’s Untitled, consisting of discrete yellow geometric forms, were meant to be manipulated, reassembled, and interacted with by the viewer, encouraging curiosity.

The last segment of the exhibition focuses on another key strand related to the development of Kineticism: Optical Art. Engaging with viewer’s visual perception, this artistic style often incorporated the illusion of kinetic movement into its dynamic experimental works.

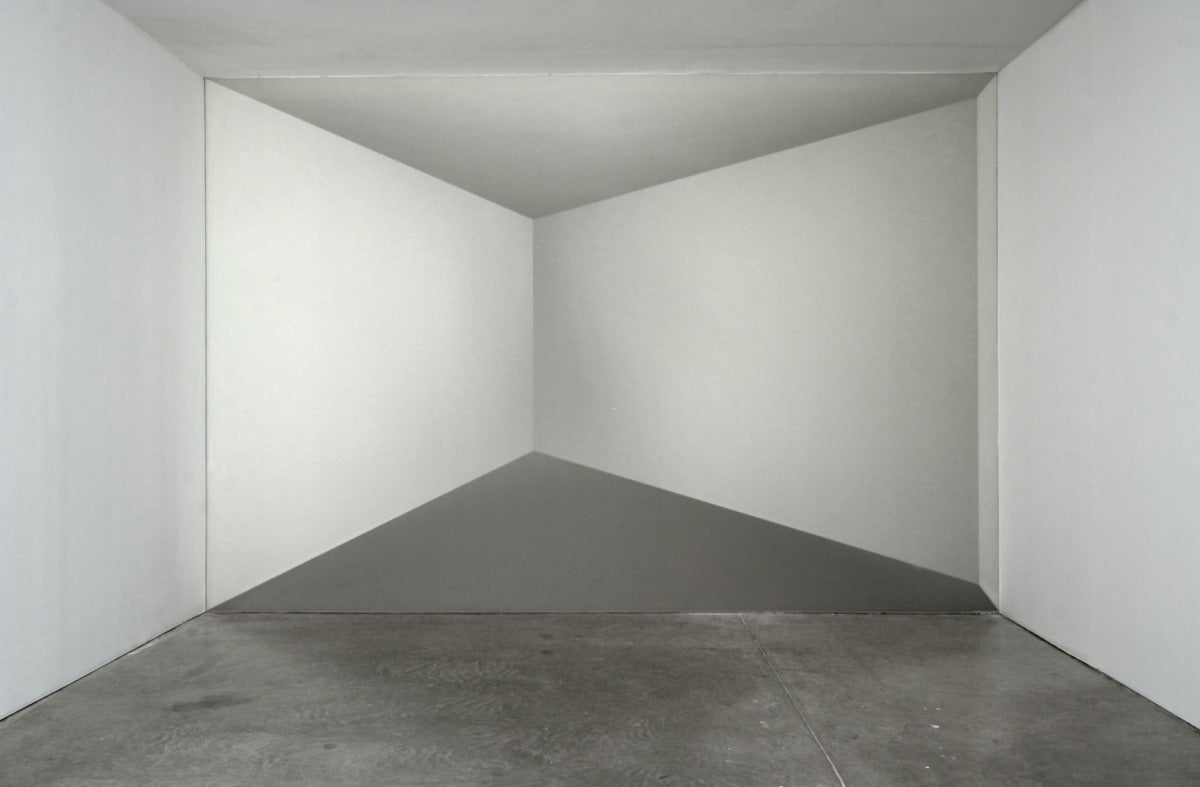

A particularly poignant representation of this art movement is Ricci Albenda’s silent film, Panning Annex (Albert). Projected onto the gallery wall, this short video displays a 360-degree loop of an undefined and unamusing gallery wall. Viewing this rotating wall gives visitors the optical illusion of moving as well even if they are standing stationary. Thus, Albenda demonstrates how optical effects can also engage with one’s physical orientation by creating the illusion of movement.

Movement is an ambitious exhibition. It seeks to bring together principal twentieth-century avant-garde movements and their afterlives into a singular show. In part, it achieves this curatorial vision – a wide breadth of artists, working in different mediums, geographic areas, and time periods are well-represented. Yet, at times, this ambition can feel overwhelming thus making the exhibition’s goals unclear. Aside from the gallery, “Before Kineticism: Utopia and Utility in the Avant-Garde,” it can be difficult to track the relationship between these multiple art movements, even with the assistance of didactics such as wall label texts. The lack of strong spatial separation to distinguish each art movement likely contributes to this effect. Moreover, the gallery space can feel too big at times in comparison to the displayed artwork. For example, sculptures by Clark and Oiticica are almost dominated in scale by the large walls in which they are hung. Furthermore, the presentation of the jewelry display case in the open gallery space forecloses the opportunity for intimate looking that the objects warrant.

Despite these shortcomings, Movement belongs to a larger lineage of curators and academics who have explored the relationship between Latin American contemporary art and global avant-garde styles. Perhaps more importantly, the sensorial interplay among objects and materials leaves an indelible mark on the visitor, encouraging one to meditate on the significance of the affective dimensions of art.

Movement: The Legacy of Kineticism is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art through July 16, 2023.