This week, we asked artists, writers, nonprofit leaders, gallery directors, and others across the South about how they are navigating the dramatic changes to daily life brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Isolation, job insecurity, the threat of sickness and/or starvation, social stigma and assumptions of the irresponsibility of others around you, and possibly yourself—that’s just a regular ol’ Tuesday in rural Mississippi! When the world went into an unwanted isolation with no real view of what the future can provide, I was like, Nailed it already! Behold the expert!

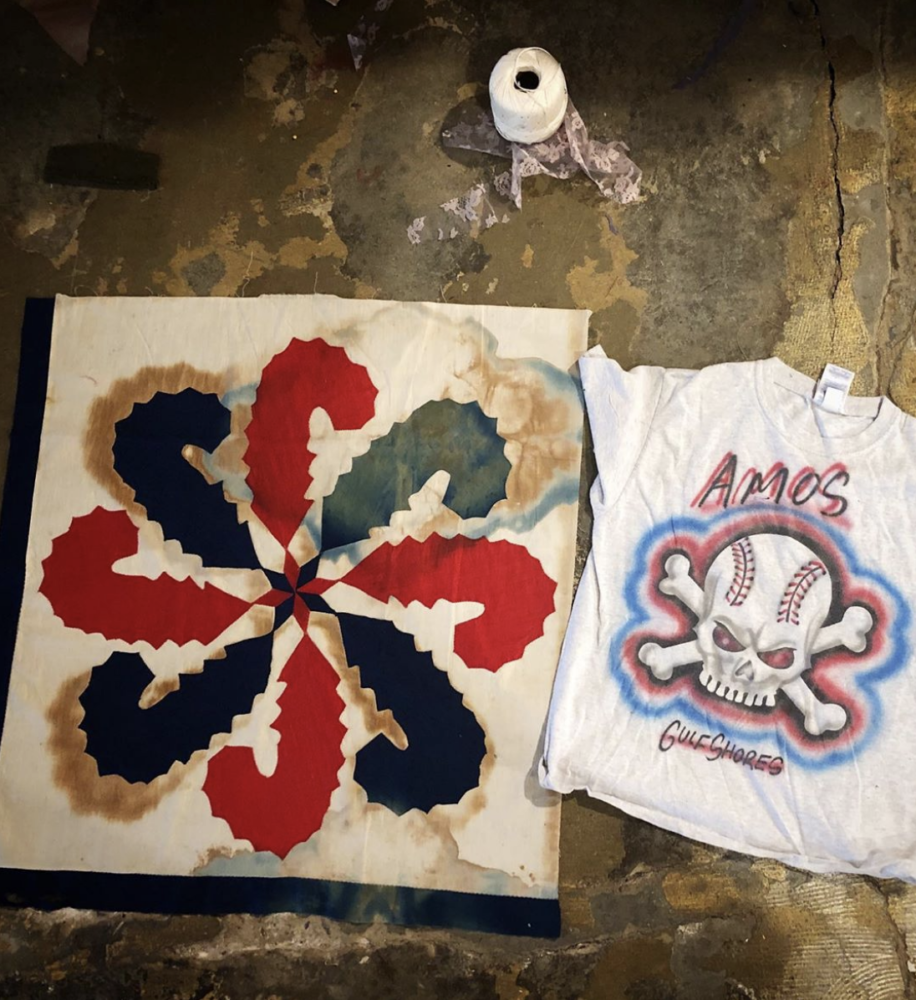

As a waitress, I lost my job weeks ago. As a textile artist, I barely had one to begin with. I can now add “Recipient of Unemployment Grant 2020, generously made possible by the United States Government” to my résumé. Like all mothers, I’ve had to homeschool my children. I’ve focused on lessons such as specialized fabric-folding techniques I utilize in my studio (colloquially known in some cultures as “laundry.”) The thought of my children practicing this ancient art motivates me when I’m working before dawn in a near futile effort to get some studio work done before they wake.

Even though my gallery-owner boyfriend and I look across the sofa at each other at least twice a day with utter panic for our hard-fought artistic careers, I’ve found a way to be thankful. Thankful to have been taken back to when I first started. Sewing just to sew. No anticipation of an audience. No show. No write-up. A nameless woman who makes quilts. The freedom of intention that the craftwomen before me, my heroes, braved every single solitary day of their lives.

Just me, the fabric, the needle, the thread. I’ve sewed my way out of real bad situations before. I can do it again.

Coulter Fussell, artist, Water Valley, Mississippi

Here in Nashville, we’re under a long-overdue “safer at home” order. I wrote for Buzzfeed Reader about what we’ve been going through with implementing social distancing measures right after being displaced by the tornado. In the professional realm, we freelance writers have been staying connected through online communities like Study Hall, cooking up mutual aid efforts and sharing resources. On a personal note, my husband is an ICU doctor at Vandy, and though I’m very proud of him, I’m also worried. My coping plan for all this is to write through it (and cuddle my dog a lot). If anyone in the middle Tennessee area needs anything, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

Jennifer R. Bernstein, writer, Nashville

Murmur slowly canceled events with the South Broad Street Market, then called everything off. We didn’t have a reopen date on our announcement — it doesn’t seem right at the time, still doesn’t. A former audio product client from my advertising days once told me “You can’t beat physics, it’s part of nature.” Predicting when this is over seems like trying to beat nature. We stand to lose a significant chunk of revenue in what is two of our busiest months.

I find myself not worried about myself. My concern and my work are for Murmur, for others—the phone calls and texts come from peers in knots that this will be it for their organizations. Art workers with no idea where their checks are coming from. Friends I’m buying food, giving supplies to, and just listening to. This is a moment for us to recalibrate from the relentless noise of commerce, politics, and every structure we have contrived to convince ourselves things were fine—because we were suppressing the internal signals that they were not, we are not. The South has developed a knack for resilience since the turn of the century. We were hit hard by the aftermath of 9/11, Katrina, the recession, Deepwater Horizon, our long-running political situation, now this. We’ve had to develop a certain kind of psychic buoyancy and bias towards action despite leadership, markets, and pessimism itself.

To paraphrase Toni Morrison, this is precisely the time when artists (and creative workers) go to work. We will have a lot to do.

Brandon Sheats, executive director, Murmur, Atlanta

I was already braced for an impact as I prepared to turn thirty in late March. But as COVID-19 slammed into the country I have felt my shoulders creep up and settle above my ears. Persistent worry—for my immunocompromised family, my parents in their mid-60s, friends and strangers in hot-spots, my job—has eclipsed the minor personal dread of entering a new decade. I recognize this path; our economic future begins to look startlingly like it did at twenty. I haven’t wanted to write, and I’ve never journalled. So instead I take walks, pull weeds from a patch of thyme in my tiny garden, make sun tea and speak to my grandmother, who is 97 and alone in her room.

Claire E. Dempster, writer and arts administrator, Atlanta

This is definitely an unusual and frightening time we are currently experiencing. We were supposed to open a wonderful show on March 20 with Whitney Stansell, Kim Truesdale and Rachael K. Garceau, but, of course, we had to postpone. We are continuing the exhibition Paper Kites/Uncertain Sky with Seana Reilly and Morgan Alexander. When we were planning the 2020 line up of shows for the year, we decided this show was the one to begin the year. And in a weird way, it is very telling about where we are in the world today. The gallery is open by “appointment only” until further notice. We are doing daily posts on social media to honor the women artists we represent as part of National Women’s Month. The Whitespace roster is heavily femme, so we are delighted to showcase these artists and their work. We are experimenting with a virtual tour of the current show. Take care and wash your hands.

Susan Bridges, owner and director, Whitespace gallery, Atlanta

Between hand washing, checking in on friends, and trying to keep our work moving forward, my wife and I are keeping a close eye on our front pasture, where our goats have been having kids for the last five days. At a time when so much seems to be fading, disappearing, going away, it’s a near miraculous sight to discover the new arrivals, sturdy and standing in their first hour on solid ground, nurtured by their loyal, tender mothers. In the goat world, when all goes well the old take care of young, the knowing teach the fledglings. In the midst of so much uncertainty and disorder, this one goat pasture offers an alternative to the news of the day, and a model for just what it means to shelter in place. May it always be.

Tom Rankin, Professor of the Practice of Art and Documentary, Duke University, Raleigh-Durham

we’ve had a curfew for almost two weeks, but the tourists keep flying in and breaking all the local laws. it is the continuation of the colonial project that, as edward said noted, prefers to imagine the colony as an empty landscape with no residents, no old or sick people. today the governor announces if they will extend the curfew. meanwhile, there is very little testing and even the most conservative predictions are alarming. it feels like maria all over again, except now we can’t even see the ocean. my people are generally gregarious and social. of course, no one is built for this, but it feels particularly hard to imagine boricuas not talking, not sharing, not touching. i miss saying hello with a kiss on the cheek.

Raquel Salas Rivera, poet and translator, San Juan, PR

Mostly, I am running into impasses with my sewing machine and then flopping on my bed to search Facebook groups for a replacement. I tilted a mattress to the wall to pin my projects to. I am calling my friends and relatives asking if they can take care of me if push comes to shove and asking if they do care about me now. I am going out of my house at night with a flashlight to search for the limits of human love, a periphery laid in glistening snail tracks.

Margaret Jane Joffrion, writer, Nashville

I’m very angry, and I honestly don’t see a positive way out. A lot of trauma from Hurricane Katrina is resurfacing, and the same impotent rage I felt then as a girl of 16 is ramped up now as a woman of 31. Whole communities are going to be decimated, and I sincerely do not feel like anyone is taking it as seriously as they should. Talking to Kristina [Kay Robinson] and Raquel [Salas Rivera] about the similarities between this and Katrina and Maria makes me nervous. We know. We’ve been here before. As usual, this will hurt the poor, minorities, rural areas the hardest. For decades. None of my roommates have any sort of protection—working in construction, retail. I’ve been under extremely strict quarantine for weeks because our friend is living with us after fleeing his neuroscience program in Milan. So many people will die. I don’t know many artists with health insurance, much less something comprehensive.

I find the creative response to this crisis infantilizing and demeaning. There is of course, a need for positivity and hope because, as a race, we desperately need it to survive. But I don’t need Good News Newsletters and another article about how to entertain yourself during this seemingly ceaseless parade of hours. I didn’t need people writing funeral dirges for New Orleans in 2005 and reminiscing about that one Mardi Gras they went to in college—I needed concrete information, money, and directions on how I could get home. Right now I need concrete information, money, and directions on how to live as a person with five other adult humans who aren’t being protected by this government and are risking their health every day. I don’t need a newsletter full of cat videos.

Jasmine Amussen, writer and editor, Atlanta

I had been pretty actively following the coronavirus outbreaks around the world with a growing sense of dread for a couple months. By February 25, Mardi Gras Day, I returned home to the hear the CDC’s warning to prepare for the reality that life in the United States was about to change dramatically. This was followed by a two-week lull of frustrating inactivity from the federal government and assurances that the virus was under control. “Pretty close to airtight,” was the quote from the National Economic Council director Larry Kudlow on February 26. By March 2, I had read the CDC whistleblowers’ account about exposed healthcare workers receiving passengers of the Princess cruise ship without personal protective equipment and little or no training. On March 11, I received a letter from my son’s elementary school that a student had a family member who had been exposed to coronavirus. Our quarantine began the next day, and we haven’t been further than the corner Walgreens since.

So much of the personal is collective and the collective personal in New Orleans. Social distancing and stay-at-home orders have halted so many of the communal activities that define life here. I, like so many people, have lost income since this crisis began. I’m afraid for my city, where so many people work as gig workers and as a part of the tourism economy, which is our only industry. I fear that so many of the vulnerabilities and inequities that led to loss of life during Hurricane Katrina will prove themselves deadly again in this crisis. Personally, I have had the trajectory of my life upended before. In 2005, during Katrina, in 2008, during the financial crisis, and, in 2009, with the sudden death of my son’s father. The calendar of things that were supposed to define my life in 2020 have been put into precarity, and I fear the security I have worked so hard to build being lost again. I know, also, that so many people have much less than I do in this moment. Privilege and vulnerability being such slippery states.

I am taking it slow. This is the first new thing I’ve written. Today, I’m counting every day my son and I rise and wake again as a victory. It is imperative we survive. I’m doing everything I possibly can to ensure we do so.

Kristina Kay Robinson, writer, artist, and educator, New Orleans

During this time of unprecedented uncertainty and public concern, Burnaway has compiled a list of useful resources for artists and their supporters here.