To encounter Diana Al-Hadid’s work is to step into a liminal world, a tense and poetic in-between where illusory structures and figures appear suspended mid-mutation. The Brooklyn-based, Syrian-born artist transforms materials like polymer gypsum, fiberglass, bronze, steel, and aluminum foil into labyrinthine, monochromatic sculptures and wall panels that seem both solid and liquid, still and moving, vestiges of the past and beginnings of a time yet-to-be.

It is fitting that Sublimations, an exhibition of Al-Hadid’s recent work in Nashville, is concurrently on view at two of the city’s foremost cultural and historic landmarks: the Frist Art Museum and at Cheekwood Estate and Gardens. The exhibition presents sculptures, wall panels, and drawings from Al-Hadid’s first major public art project, Delirious Matter, commissioned by the Madison Square Park Conservancy and mounted in 2018 throughout the New York park.

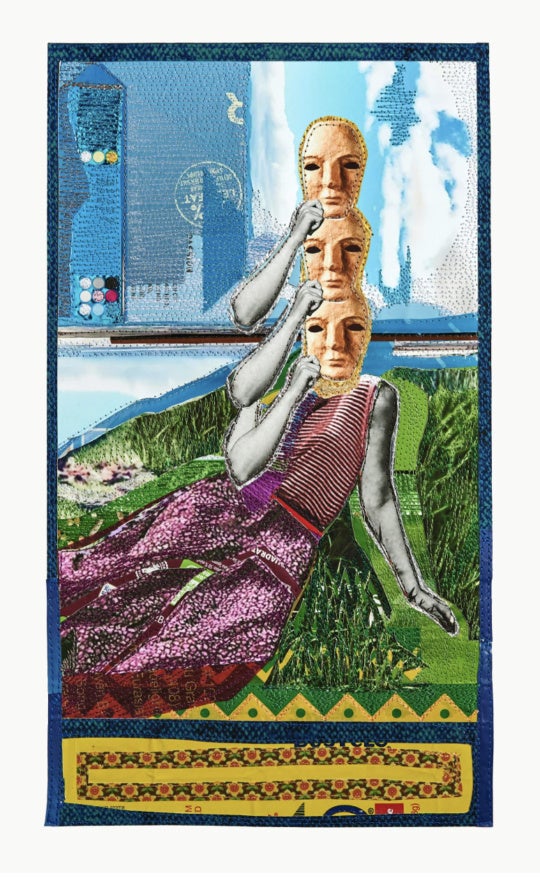

Like much of Al-Hadid’s work, the selections here blur the boundaries between painting and sculpture, synthesizing architecture, abstraction, and figuration to reimagine two-dimensional concepts within three-dimensional space. These works are dense with allusions to classical paintings, architectural monuments, ancient maps, stories, and archetypal images of the female form, both from Western and Eastern traditions. Inspired by the female character in Wilhelm Jensen’s 1902 German novella Gradiva, a large-scale sculpture of the same title on view at the Frist resembles an arched wall of white flames enveloping a walking female figure, who is faintly visible through swirls of pale blues and greens. The two sculptures installed outdoors at Cheekwood include The Grotto, the companion wall piece to Gradiva, and Citadel, a mountainous form inspired by Hans Memling’s 1475 painting, Allegory of Chastity, appearing as a female figure protruding from a voluminous skirt. Two stunning figurative sculptures at the Frist, In Mortal Repose and Synonym, reinterpret the classical female figure in repose as headless and melting off its plinth.

It is tempting to read Sublimations as an art historical feminist critique or as attempts to render the passage of time and the tenuousness of the monumental. But Al-Hadid provides no sure footing when it comes to the ideas behind her work. What is clear, however, is her interest in experimenting with how we experience space, dimension, mass, and interiors and exteriors. The resulting work reimagines traditional motifs and pushes the boundaries of sculptural practice and possibility.

I recently spoke with Al-Hadid about her process and her current exhibition in Nashville. Our conversation was conducted via email in June 2019 and has been edited for publication.

Melinda Baker: I’m curious about Delirious Matter—what guidelines, if any, did you have for this project? How were you inspired by the space of Madison Square Park?

Diana Al-Hadid: I had the guidelines of the physical dimensions of the park itself, the various regulations for built structures that the city of New York requires (the works have to withstand hurricane winds), and, of course, the highly public nature of the park itself in the middle of Manhattan. I made six works for the show, all with deep consideration of the park’s lawns, sightlines, traffic patterns, and history.

MB: How did history become so crucial to your work?

DAH: I studied art history in college, and I love how history is always shifting and changing. There always seem to be so many more histories to uncover. I don’t think of what I do as seeking out inspiration as much as a pursuing a curiosity, however. I wonder along with you about why I’m drawn to the things that I’m drawn to.

MB: Can you elaborate on that idea of “pursuing a curiosity” versus “seeking out inspiration?”

DAH: I think what I mean is that I work from a point of personal curiosity, not external dictation. I don’t know everything ahead of time before I start making something. I don’t know what shape it will take, and I don’t know what I’ll learn as it starts to take shape. Even if I do know a little something at the start of a project, it’s usually not concrete. As an artist, I become curious about something, so I investigate it with tools—both material and historical. In the process of making, I become recommitted to my world, and therefore become more and more interested in it because I am investing more and learning that there is always more to learn. This only makes me want to make more to learn more. In short, I learn about the world through my work; it’s my best way to engage and understand and to keep myself curious for more. It’s much more cyclical or multi-directional than having an idea and then translating or packaging said idea into sculptural form for an imagined audience to then know and feel satisfied, like they just ate a slice of pie. I’m not interested in making this kind of didactic sculpture. It’s a discovery for me as much as for the viewer.

MB: You transform industrial materials used to reinforce the infrastructure of buildings or cityscapes into organic structures that appear to be dripping or melting. Wax, stalactites, stalagmites come to mind. What do you like so much about materials, like polymer gypsum, you often use?

DAH: I love all variety of construction and sculptural materials, and I experiment with them regularly. I certainly had some insights along the way about how these very contemporary materials can be pushed or used in a new manner, but it would be rather technical to explain. I try to keep an open mind about what to work with, but I like to make everything myself and I want to know as much as possible about a material or process before I use it.

MB: The exhibition title, Sublimations, suggests transformation, and most of your work looks like it’s in the middle of a dramatic transition. Are transitional, in-between states of particular interest to you?

DAH: I tend to feel more comfortable in the middle. Maybe because I am a middle child, maybe because I am between cultures, maybe because women have always had to be several things at once. I tend not to trust fixed or hard definitions of things, so there’s that. I think all artists suffer from the same suspicion of absolutes.

MB: Your work is three-dimensional but painterly in so many ways. The tricky physical feats of illusion you pull off with sculpture are much easier to accomplish with painting. And yet, you seem determined to push the boundaries of what sculpture can do, gravity be damned.

DAH: Yes, I have painting envy for that reason. Gravity is sculpture’s first problem.

Diana Al-Hadid: Sublimations is on view at the Frist Art Museum in Nashville through September 2.