After a 44-year (and counting) relationship, it is only fitting that David Driskell’s first posthumous retrospective opened at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. The survey Icons of Nature and History contains sixty works of art created between 1953 to 2011 and opened less than a year after the artist’s death of COVID-19 complications at the age of eighty-eight. His relationship with the museum was extensive, beginning in 1977 when his seminal traveling exhibition: Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950 was presented in Atlanta (the exhibition was first mounted at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art). It was a first-of-its-kind extensive exhibition with more than 200 works by sixty-three African American artists and many unknown artists. Later, Driskell, an avid collector, and prolific curator, opened two concurrent shows at the High in 2000: To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Narratives of African American Art Identity: The David C. Driskell Collection. In 2005, he partnered with the museum to create the first national award honoring contributions to the field of African American art and art history, the David C. Driskell Prize.

Of the many things David Driskell was throughout his life –a teacher, scholar, writer, collector, mentor– he was always an artist. His practice bridges numerous styles and movements, blurring borders between figurative, narrative, and abstraction, between cosmology and mythology, spiritual and personal fulfillment. He seamlessly shifts between African and European iconography, playing with color, pattern, and collage. Frequently the works serve as moments of calm, despite being made in unsettled times. I went into this exhibition somewhat inclined to appreciate whatever was on the walls. For eighty-eight years, 88 (!), he was a stand-alone visionary, an unrelenting advocate for African American art history to simply be called American art history. Driskell reshaped the canon of American art, but what does that mean walking into a deep look at his own artistic practice? Despite feeling a bit uneven (primarily when too stylistically similar to his peer Romare Bearden), at its best, Icons of Nature and History is brilliant.

David C. Driskell, Memories of a Distant Past, 1975; egg tempera, gouache, and collage on paper. Collection of Joseph and Lynne Horning, Washington, D.C.

© Estate of David C. Driskell. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York.

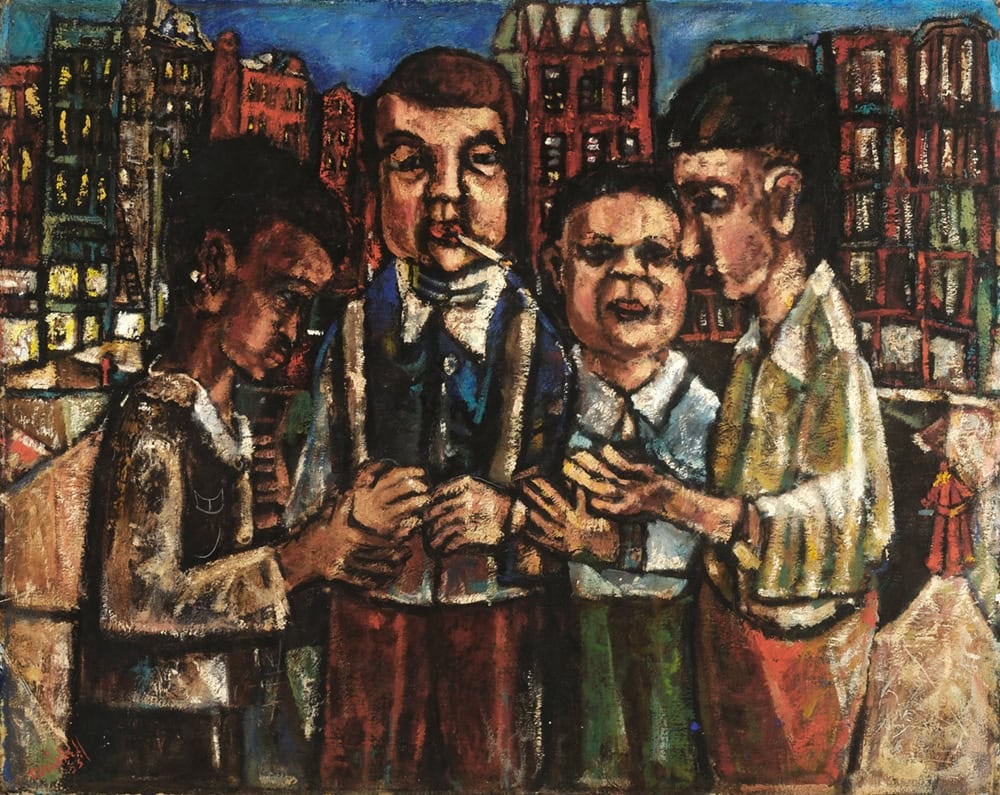

One of the earliest works in the show is City Quartet, 1953 depicts four boys gathered in a tight cluster. Shoulder to shoulder, they mimic the snugness of a row of New York brownstones that soar above them. It’s a classic tale, a Southern boy in the Big City. Driskell’s formative years were spent in western Appalachia. Still, in 1953 as a junior at Howard University, he was granted a summer scholarship to the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine. At the time, he had never been north of Baltimore. In Maine, he studied with the Social Realist painter Jack Levine, who made satirical social commentaries on modern life. At the end of the summer, the train trip back included a layover in New York City. The proverbial mind was blown. This summer of 1953 marks his beginning to believe himself a professional, mimicking some of the older Levine’s techniques. Big, round, bloated faces, umbers, burnt siennas, brick red, dapper collared dress shirts. In Driskell’s vision of the 1950s kids did not smoke, yet in cosmopolitan New York, four young artists trying to declare their independence huddled over a single cigarette garnered no attention.

Two years later, Driskell was teaching at Talladega College, an HBCU in Alabama, when 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi. After a contingent from the campus marched downtown demanding integration, the Ku Klux Klan began a terror campaign, including shooting at the campus. Fed up with the inhumanity surrounding him, Driskell stayed away from works as overt protests and began painting pine trees. They were a distraction. It was a mutual relationship in a world full of hate: he loved nature, he loved trees, and they loved him back. They gave him everything. He painted them in the morning. In the dark at night. He painted their leaves dancing in the wind. He anthropomorphized them, trying to probe their thoughts and feelings, getting deep to the roots.

In Behold Thy Son (1956), Driskell paints a commanding tribute to a crucifixion. Like the strength of his beloved pines, Till stands like a tower, a classic Christ-like figure, arms extending beyond the canvas. His lean body is an extended palette of visceral flesh tones, made all the brawnier with the artist scratching and scribbling the surface. An intensely gory wound on Till’s lower abdomen is partially obscured by a mother Mary figure who has loosely wrapped her arms around the body. The lower right corner holds an elaborately carved sarcophagus, Till’s open casket marking the loss of American innocence. Everything happening in the South was suddenly visible. The image of hate could not be unseen.

There is the old saying that artists head to Maine. After his Skowhegan summer, he purchased a summer home in Falmouth in 1961. He would drive north each May to begin tending to his garden before returning in June to paint. Pine and Moon (1971) is a visual representation of what it feels like to open your eyes to a pristine Maine morning. The blueness is big and bold, free to spread in every direction. There is cozy chaos to how the hazy tangerines dance with nimble mauves, flat colors fighting for attention. Just as your eyes start to see it, to grasp this invitation to a fresh day, the color changes again. Maine is the “Pine Tree State,” the only thing to pierce the landscape are the 80-feet of smooth, thin, a hundred earthy hues of green, red, brown trees jutting up towards the heavens. At his home and studio in Falmouth, Maine, we’re surrounded by them. Living up to 1,000 years, he planted them between various homes to memorialize family, friends, mentors, and ancestors. Pines connect the past to the present, the present to the hope of tomorrow. Driskill’s pine paintings feel almost figurative. He would paint the pines with unencumbered, jubilant brushwork, letting the spiritual energies take the wheel. Ultimately, he depicts nature as a release. One of my favorite moments in the exhibition is in the upper right corner of Pine and Moon; it’s a perfect radiating outline of a luminous moon, frozen in place, softly bathing in the milky light of day. There is a grace to its looming presence, firm and faithful like a beating heart.

In 1936 the Driskell family moved to a thirteen-acre farm near Polkville, North Carolina. Isolated twenty miles from town, where only one Black doctor practiced, there was a genuine need for self-reliance. No telephone, no house calls. Specialized healers relied upon instinct, intuition, experimentation, and an inter-connectedness to ancestral homeopaths to maintain a family’s physical and spiritual health. In The Herbalist (1999), Driskell depicts a lone Black body like an African totem, perhaps representing his mother, a practitioner of the oldest form of medicine known to humankind. Standing within an outlandishly luscious botanical landscape of explosive red and cobalt blue paint streaks popping out of otherwise dark woods. Serpent-like green collaged leaves climbing up around the figure, trees of life are nearly interwoven to the body’s outline. Devotion, spirituality, personal energy … the healer is at one in her Garden.

Summing up a survey that spans seven decades is a daunting task, but The Herbalist is the unquestioned start. The painting feels the most personal—the most certain as Driskell, so beautifully orchestrates numerous cultural legacies of the African diaspora into a single plane. While his writing sought to reach a wider audience, Driskell’s art most hummed with ideas, memories, and wishes for an old world to step into the new. He never chased fashion. He made discoveries, shared them, and then moved on. As a whole this exhibition opens a window into his desire to depict love, despair, esteem, and exchange, his canvases or prints are filled with longing. He never stopped being excited about making art. Driskell was a true titan.

David Driskell: Icons of Nature and History is on view through May 9.