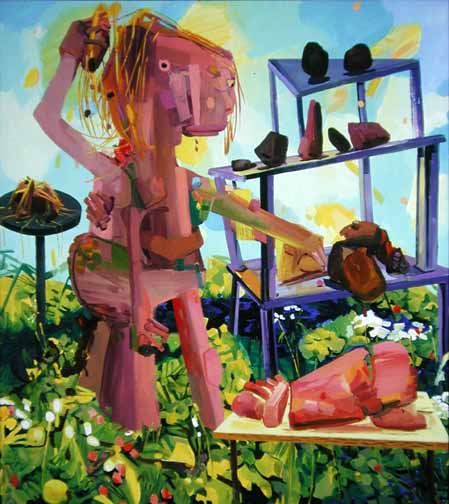

Dana Schutz burst onto the New York scene in 2002 with her brightly colored canvases in which malformed denizens act out strange scenes of violence, self-mutilation, and self-contemplation with an almost child-like innocence. Schutz was in Atlanta for the opening of Drawings & Prints, her exhibition at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, and was kind enough to sit down with me after the artists’ panel to talk about her show, her recent turn to drawing, and why she doesn’t like stripes.

Charles Westfall: This is the first time you’ve done a show of drawings and prints. Was it something you’d been wanting to do, or was it an idea that ACAC approached you with?

Dana Schutz: It was both, really. Stuart Horodner approached me about it, but it happened to be at this moment when all I’ve been wanting to do is draw. I had been making drawings of all of these off-hand, made-up portraits — like twenty a day — just to get used to the brush and the ink. And it felt really good. Drawing is a completely different head space. I’ve been feeling like I need to be drawing to get where I want to be with my paintings.

CW: You’re still talking about using a brush though, which for a lot of people equates to painting, right? So how do you define drawing as a separate practice from painting?

DS: There’s something about painting that feels more real; there’s actual physical material there. With drawing I always feel like it’s dust, like it’s not a real material. Drawing becomes more about “line quality.” And I tend to draw in black and white, so it becomes even more about line, and how lines activate the white of the paper to make space. In painting the space and the image can actually be built into the material itself, whereas in drawing the space of the image exists between marks on a page, which is a much more abstract concept. So it’s been more difficult for me to work toward a kind of drawing that I can accept and feel comfortable with. But it’s been a challenge that I’ve really enjoyed.

CW: Is that what you mean when you say that drawing is a different “head space?”

DS: Yes, but also it’s a different mental space. I think the thing that’s really exciting about drawing for me is that the feeling of judgment is very different from in a painting. The drawings that I really respond to are usually like Bruce Nauman’s drawings; they have a kind of energy to them that’s closer to thought or notation. They’re not about trying to make great, finished drawings. Drawings are more suggestive than paintings, so with drawing you always have this question of when is it enough? Sometimes a drawing can be really off-hand, and maybe not be quite enough, and yet somehow it still works and is stronger than a drawing that’s neatly rendered and totally filled up. It’s like with those portraits I was talking about; I could do a hundred of them and maybe only one would be good — but that’s OK. And then you’ve got something: You’ve got this one drawing you like.

CW: That kind of goes back to what Stephen Schofield was saying during the panel: drawings are allowed, sometimes even encouraged, to have a kind of awkwardness, and that can somehow give them a greater sense of authenticity.

DS: I loved that! He was talking about drawing in a cardboard box; I was getting this mental picture of him inside a big box, being kicked down a hill or something, and he’s in there trying to make a drawing! [laughs] Blindfolded or something, who knows.

CW: The press release for the exhibition talks about your use of drawing as an “exploratory” medium. As a painter, how does exploratory drawing compare to the traditional notion of preparatory drawing?

DS: Well all of the drawings in the show relate to paintings that I’ve done. Two of them —Swim, Smoke, Cry #2 and Talk Talk — were actually made after the paintings, so they’re like the opposite of preparatory drawings. The image was already organized, but the drawing gave me the chance to change it by moving it into another material where it could express different things. Usually, if I’m actually drawing to prepare or sketch out an idea for a painting, it ends up almost like a game plan drawing; it’s very loose and schematic. With the painting Face Eater (2004) it was actually really tough. I had made a version of the painting earlier, and it just didn’t work out; it looked like a mess. So I started making drawings, and even the drawings were very difficult to figure out. How can it still be a face when it has no face, you know? You need two eyes for it to be recognizable. So that was a case where the drawings were really helpful to organize the structures and plan how to actually build the image.

CW: But those aren’t the kind of drawings that you’re showing here, or are they?

DS: Well, one of them was! [smiling] There’s the one of a person being poked in the eye. That one is preparatory, where I actually really liked the balance of the drawing, so I took it directly for the painting. With the others it’s there, but in a more roundabout way. Because you take a drawing that you did, for example, where you know you liked a part of it or worked something out in it, and then those parts work their way into something else.

CW: The drawings and prints in the show span a period of about ten years; do you feel that your relationship to drawing or printmaking as a practice has changed over that time period?

DS: I think it has totally changed! I was invited to be in a drawing show in 2002, and I panicked because I was like, “I don’t show drawings!” I haven’t even made a “finished” drawing since undergraduate school! So then it became a decision: How do I draw?

Initially it was a real struggle, trying to figure out how to draw in a really honest sense. I didn’t want it to become just a process, like patching a hole in a wall or something, just a series of steps. I used to be so afraid of paper; I would just touch it, and it would be destroyed immediately. But now I’m feeling less afraid, and I’ll just tack some up on the wall and start drawing. Coming here for the artist’s talk and panel and everything, I was really scared and thinking, “How am I going to talk about drawing before a panel?” I don’t even have a clear way to articulate what a drawing is.

CW: You’re one of the most recognized painters of the last decade; was there a moment when you felt like you’d arrived?

DS: The whole thing was a huge surprise, a surprise that people actually responded to the paintings. But then it was also a really intense time in New York and in the art world, because it was the beginning — right on the cusp — of this big art boom. And I think that amplified a lot of things. That part was really uncomfortable. At first it was super exciting, of course, because you were like, “Oh my gosh, there’s actually people at the show who I don’t know!” But then it got tricky, because, around 2003, the art world exploded in a completely different way.

DS: And do you think that affected your career?

I think it affected everyone’s career, because it amplified everything that was there. And it distorted a lot of narratives. It just seemed really alienating; I guess that would be the best way to describe it.

CW: I think that one of the reasons your work has been so successful is because it satisfies a need that each generation has to identity a voice from among its own ranks that can serve as a unique and timely vision of the existential crisis. How would you respond to that?

DS: I think that early on that was a really important question for me. It was actually the question of how to make a painting that I felt really excited about at the time. A lot of contemporary painting back then seemed like it was telling you that it was weird to make a brush stroke unless it was somehow a fixed quote. And I was savvy; I read all the theory of all the reasons why you couldn’t just make painterly paintings. And, you know, Luc Tuymans was so seductive, and people were making paintings that came from photographs, because the language of photography in painting implies a kind of distance. So the question was: Could you make a painterly or even colorful painting that didn’t have that kind of distance? Or would it just be read as completely naive? So, if you wanted to do it, it was going to be at the expense of seeming out of it, at that time.

CW: But you were willing to take that risk?

DS: Yes. Because, like you said, every generation, there’s always the question of: Why does it have to be this way? I’m sure painters who are emerging right now are going through the same thing: Why does it have to be this way? Or, why can’t it be …? Et cetera. You know?

CW: And, as an artist, you have to move into that unknown territory?

DS: Yeah. Like why does there have to be so many … stripes? [laughs] Or whatever. I don’t know what I was saying there about stripes.

CW: You were making fun of them.

DS: Hey, I like stripes! I have no problem with stripes.