It’s no coincidence that Crystal Jin Kim shares her name with a mineral known for its depth, clarity, and multivalence. Her body of work spans a variety of mediums—from film, to painting, to ceramics, to sculpture—yet each carries with it the unmistakable impression of her touch. At every possible turn, she reminds the viewer to remember where they come from, to be conscious of how each work of art is borne from absolute humanity.

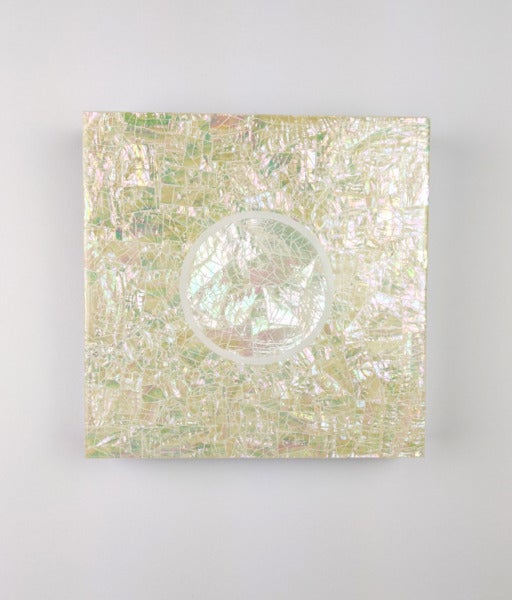

I first met Crystal at Year of the Rabbit, an art exhibition that I curated in January 2023 celebrating the work of AAPI artists in and around Atlanta. Her work immediately stood out: two wooden blocks, with intricately carved pieces of mother-of-pearl overlaid neatly on top, and a circular panel that shone like the moon of an alien planet. She explained that the works were inspired by najeonchilgi, a traditional Korean art form that uses mother-of-pearl to craft iridescent scenes of nature and geometry.

I sat down with Crystal over Zoom to discuss her position as a Korean American artist in the American South, the role family and Asian mothering play in her work, and mark-making as an invitation for viewers to come closer and imagine the ephemerality and transience of the human experience.

Karina Teichert: As an Asian American artist, do you feel that you face any particular challenges in the art world? Do you feel that you’ve been able to network and build community with other AAPI artists?

Crystal Jin Kim: That’s a great question! I do feel like I’ve been able to grow a lot as an AAPI artist, and I’ve connected with a lot of people. There’s not a collective in Atlanta, but there are a lot of events, and it’s growing more and more. I grew up in Georgia, went to college at Northwestern, and then moved back in 2014 after graduation. Back in 2014—and it might have just been my lack of experience—I don’t think it was as connected within the Asian American arts community in Atlanta as it is now. I remember being so excited to find other Korean and Asian American artists. In Kyoung Chun is someone I love and respect; I saw her show opening on Facebook in 2015, and she’s now a mentor and friend to me. I’m encouraged by Asian Cultural Empowerment, a nonprofit organization that formed about two years ago. I was in their first exhibition in December of 2021. I didn’t know it was a competition or that there was going to be an award, but I got one! They exist just to support AAPI culture and arts, so I’ve been helping them get connected with more artists here.

KT: Do you think that there is a specific kind of relationship with the Southeast that you have as an AAPI person? We’re not really super well-represented here!

CJK: You know how they say that the South has something to say? Atlanta creates culture. I was born in Atlanta, grew up in Marietta, and currently live in Doraville off of Buford Highway, and I love it. Asian Americans in the American South are definitely not well-represented. I have a few friends who are Korean American and have heavy Southern accents and people are always so surprised. When I went to Chicago and told people I was from Georgia, they were like “What? There are Asians there?” There’s something about Metro Atlanta that’s so beautiful and rich. There’s something about color and light here that’s unique to the South. I didn’t realize it until I lived in other places. I thought the sun was just the sun, it was just hotter depending on seasons, but I realized even on the hottest, brightest day in Chicago, the light and color looks totally different than here at the same temperature. Subconsciously it informs our arts and film practice, our sensibilities are really different. Of course, racism and the narrative around that experience…it’s everywhere but it’s definitely here, too. I do feel, in media, that it’s starting to become overly-depicted, as if “Only the South is racist” when that’s not the case. That is something I’ve been thinking about: telling stories that are specific to Atlanta and Asian Americans.

KT: I’ve noticed the South’s color and light phenomenon that you’re talking about too! It’s almost like it’s always golden hour here. Do you think that informs your mother-of-pearl art specifically? That medium plays with light really well!

CJK: Yeah absolutely. The mother-of-pearl art has taught me to work more intuitively, and to pay attention to the material and to nature, and to the environment the works will be in. I’m looking at my pieces as I’m talking to you; in a given day, depending on the direction of sunlight from the windows, the same piece will look radically different. That’s something I really enjoy about this medium: it’s really living in the space with you.

KT: Segueing off of that, because a lot of your work is iridescent by nature and shifts depending on the angle from which you view it, how do you think that individual (and even societal) movement plays into your work?

CJK: I enjoy pieces that interact with the viewer, and that goes for both movies and visual art. There’s a conversation that happens, and I love works that have a lot of details that amalgamate into one whole and invite the viewer to look more closely at something. I think of them as an invitation for people. Gestures are really interesting to me. As we live our lives, we make thousands of movements per day. The way in which we move our bodies and the things we do with our hands tell a story about who we are as people. I wanted to work with something that made the mark visible; every single cut I’m doing is with a small blade, and they’re visible if people look. There’s the remnant of my hand’s movement, but also the invitation to move closer for the viewer, and to move around the piece and consider all the different aspects of it. That’s something I love to do with my characters too; I present one thing that makes you think a certain way about the person, and then I show different facets as we delve deeper. I’m also thinking about devotion and our caregivers, the millions of hours they spend on chores or carrying us as children. Those things go unseen, like our mothers working late into the night. Things like that really stick with me, and I think of these things as gifts to the viewer: something you can see that has the idea of devotion behind it.

KT: In one of your previous interviews, you got emotional talking about your mom, which I do a lot as well. As a child of an Asian mother, I think a lot about how my upbringing influenced the way I move about the world. You mentioned that your family is incredibly supportive and that you wrote Jinju with your mother in mind. Can you speak a little bit more on your relationship with her and how that shaped the artist you are now?

CJK: My mom works crazy hard, and she shapes me the most of any person. Witnessing her long-suffering nature, her kindness, care, and sacrifice means so much. She, my dad, and my whole family have been encouraging about what I do. If I had become a doctor, lawyer, engineer, or whatever else, they would’ve been equally supportive. I was very driven, so they didn’t feel they had to force me one way. They prayed and trusted that I would do my best, whichever path that was. They were strict, but it wasn’t like I could only do certain things for my career. I wasn’t pushed into that situation until I started dating my now husband (who’s a doctor), and began to feel that comparison and pressure. I never felt I was below anyone else until that point. Other people were putting that on me and on us, and of course he didn’t want that at all either. It’s unfair, in our society—we talk too much about Asian parents only wanting their kids to be doctors, lawyers, engineers. It’s not representative of the whole. People don’t mean to do this, but it can feed into the model minority myth and the generalization that we have Tiger Moms who solely want us to succeed and whip us otherwise. We have complex, loving parents who want the best for us, and each family views that differently. Of all of my Asian American friends, a couple are doctors, a couple are lawyers, and a few are engineers, but most of us are doing all sorts of different things. I know their parents are super proud of them, too. Everybody, whether you have parental support or not, has struggles about being an artist and creative. It’s hard for everyone.

KT: You bring up a really good point. Whenever people talk about the “Asian Parent” stereotype, they forget that it’s a response to the immigrant experience and the product of having to fight for survival. Folks talk about it as if harsh parenting is endemic to the Asian community, when it’s actually a survival tactic in a country that is actively hostile to immigrants and people of color.

CJK: Right, my parents labored so hard to provide for us, and they just wanted me to have a job where I didn’t have to use my body until it broke. I have so many friends whose parents have dry cleaners and restaurants; they know how hard that kind of work is and they want their kids to make a living, survive, and live better than they do. It’s a beautiful, loving, human thing, rather than a critical, “You’re not good enough if you don’t get A’s” thing.

KT: You mentioned in a previous interview that your mother-of-pearl art is inspired by a traditional Korean art form known as najeonchilgi. Did your family introduce you to that? How did you first find out about it as an art form?

CJK: A lot of Korean American families have a small, faux mother-of-pearl table that’s painted to be in this style, because the real deal is very expensive and precious. I don’t know why so many families have this—if it was really accessible or just something that was easy for them to bring from Korea. I grew up with one, and I’d eat tacos or do homework on it. It’s a low table that sits on the floor, and it’s a great size, especially for a kid growing up. I loved using it, but it wasn’t something I thought about until I was older. When Kudo and I got married in 2019, my mom gave one to us. I have a lot of nostalgia in general, and I try to take good care of certain objects. Even though this table isn’t real mother-of-pearl and isn’t expensive, it’s precious to me and carries a lot of memories. I was looking at it in 2020 during the pandemic and thinking “How do they make najeonchilgi?” I looked it up, but the tradition of how they craft it in Korea wasn’t accessible to me. It’s not like pottery where you can watch YouTube videos and learn the basic process and order clay online. I had to figure out my own process; I had worked with gold leaf, resin, and other precious metal leaves in the past, so I had that basis. I was able to source some mother-of-pearl from a Korean vendor online, and then I experimented and went from there. I would love to someday learn the traditional process in Korea and buy materials there. We’ll see.

KT: It’s common cultural practice in South Korea to sit on the floor rather than a couch or chair, which really grounds you (literally) in a way that other seating arrangements don’t. Is that sensation of groundedness something you seek in your art, or something that influences your art?

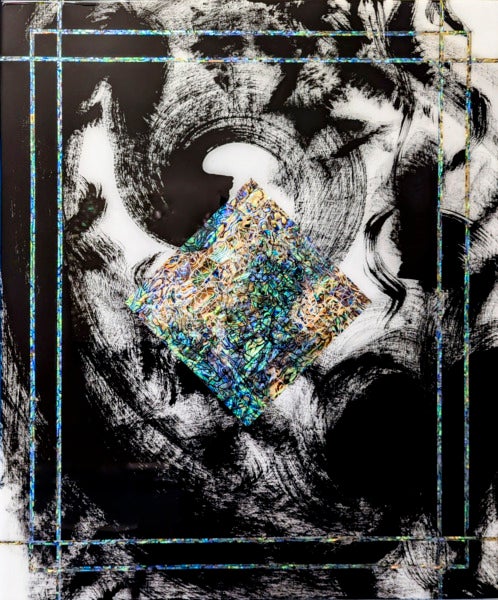

CJK: In order to keep the pearl flat, I have to be at a table or on the floor. In that way, there’s a grounded nature to it. When I work on these pieces, I feel spiritually grounded; it’s meditative, and I get into a flow. If it wasn’t hard on my posture, I could do it all day, all night, but it takes a toll on my shoulders, arms, and neck. It brings to mind Eastern calligraphy, which is always done flat on the floor or on a low table, so there’s that connection. I’ve been experimenting with mark-making, using black paint over white paint, so that the work is reminiscent of Eastern calligraphy, and then I layer the pearl over it. That technique and groundedness changes the kind of marks and movements you make on the piece.

KT: In another previous interview, you mentioned that you struggle with OCD, and that you’re trying to move away from perfectionism. What’s your inner monologue when you’re creating these works?

CJK: There are different types of OCD, and I don’t have the perfectionism OCD. I might’ve had a little bit when I was a kid, but my OCD now is very different. With these works, I keep thinking about “mental wholeness”. As I’m working, I focus on making something complete, rather than making it “just right.” If you look closely, it’s not just right. The circles aren’t perfect circles; I’m just making them fit and flow. My older pieces feel more constructed and tight, even though they’re not perfect either, because I was still figuring out the form. As I keep going now, I’ve been experimenting with different color perception and mark-making to have balance, and so that they have an organic hand in them. I often listen to podcasts or turn on shows in the background, so it’s a very receptive time for me. When I’m writing, I’m pouring out, whereas when I’m doing mother-of-pearl, I’m taking in—almost like eating—to get energy to make other things. It’s a similar feeling of completion as people who like to do puzzles; they’re not thinking about perfection necessarily, they’re just looking for the next piece that makes sense here.

KT: It’s no secret that we’ve seen a huge uptick in violent crime against the AAPI community in recent years. Do you think your work responds to that? Do you think we as AAPI artists have a duty or responsibility to call attention to the issues that our community faces?

CJK: Our art and humanity have inherent value, even when violence against us isn’t instigating conversations about them, so I always want to be conscious. I curated a show with the Korean American Coalition of four AAPI artists in Suwanee last fall. The works were awesome, and the Korean American Coalition got a grant to be used for initiatives that stand against Asian hate. I wanted to make that clear in this exhibition. We were doing that by sharing our culture, our art, and ways to connect with people. But, just as much as that, we were standing for our community. If we’re always talking about ourselves in reaction to the terrible things that happen to us, it can diminish who we are. There’s such a range of things that each artist is called to tell; there are people who are called to paint landscapes, there are people who are called to paint things that are more political, and everything in-between and beyond. It’s dangerous to push artists to make their work more “significant” by injecting it with social commentary. It’s important to have social and political messages, but they can come out in all sorts of different ways. If I talk to one person, they might not think my mother-of-pearl work has anything to do with Asian American identity—that it’s just aesthetic. Someone else could think it’s totally representative of the Korean American experience. There’s so many ways we can stand up for ourselves and who we are, take up space, speak to our value and celebrate our culture, and stand against terrible, hateful things.

KT: That was the answer I was hoping you’d give. I think about the idea of Black joy a lot, because so much of the media surrounding the Black experience centers Black pain and suffering, which has its place absolutely, but it diminishes the profound joy to be found in Black culture. Similarly, a lot of AAPI media is about our suffering and how we’re marginalized as a community. People need to be doing that work and we need to be talking about that, but if we reduce ourselves to our pain, then there’s no room for joy or art for art’s sake.

CJK: That totally makes sense, and I think about that a lot with my films. It’s vital to have films that are specifically about the Asian American immigrant experience, like Minari for example. One of my short films, Jinju, is about family: why we don’t see eye-to-eye sometimes and why we hurt the people we love most. The Korean American immigrant experience is depicted throughout that; there are flashbacks to the first generation’s difficult experience, then the second and third generation, and how it’s different for each one. But it’s just as crucial to have stories that are not specific to the Asian American experience that feature Asian American creators and actors. They have to show our full humanity.

KT: Right! Obviously we’re Asian American and our experiences as such inform the way we live our lives and the art we make, but we’re also people.

CJK: Yeah! We do taxes, we drive to work [laughs].

Watch Crystal Jin Kim’s 2019 experimental film 영원한복 Young Won Han Bok here.