Hurricane Elsa barreled up the coast in early July 2021, aimed squarely at a storm-weary North Carolina. This was not particularly notable. Unsettling and anxiety inducing, yes, but in no way novel in a state that has been pummeled by storms again[1] and again[2] with escalating[3] effects[4]. In North Carolina—and across the Southeastern and Gulf Coasts of the United States—intensifying climate change means that hurricanes have become less discrete events, and rather varied episodes in an ongoing state of climate emergency.

Crisis as we live it today is atmospheric and overwhelming. The disasters pile up, crisis folding over on itself, looping and intensifying. Unremarkably, hurricane season this year is accompanied by a slew of other (un)natural disasters: deadly heat in the Pacific Northwest, a brutal wildfire season, and a fiery oil spill in the Gulf. Generously—perhaps gratuitously— photographed, these manifold ecological crises generate a vast visual archive.

Conceiving moments of crisis as bounded events gets the question of duration wrong. We are not experiencing a good life punctuated by manageable, temporary aberrations, but rather find ourselves mired in an interminable present—one where crisis is a chronic and ordinary condition.[6] Climate change is, after all, a vast and plodding phenomenon; its destructive effects are cumulative and felt on a delay. The slow violence[7] of climate change is nearly impossible to grasp in abstraction, to say nothing of photographic form. And so, we triage the symptoms of climate change, bound to overlapping cycles of anticipation, urgent response, and lingering aftermaths. It feels like there is no exterior. Crisis is quotidian, totalizing, paralyzing. Crisis has reached a point of oversaturation; crisis has been emptied of meaning.

We all know what these crises look like: we know the deathly orange of the San Francisco sky last summer, the murk of flood waters, the jagged edges of a pummeled shoreline. Crisis images prove compulsively shareable; they enter into hypercirculation, the most horrifying among them proliferating endlessly across social media. This overabundance of imagery has a flattened, ahistorical quality. Resolutely advertising unprecedented times, crisis images deny that our disastrous present is linked, quite concretely, to the cumulative effect of petrocapitalism and a prevailing politics of abandonment. Stuck in loops of emergency response, we are unable to think or feel our way out of an increasingly unlivable present, towards historical context, root cause, or positive futurity. Crisis—as a visual form, a mode of feeling, a structure for response—proves politically dangerous.

The hypersaturation of crisis imagery we see today in some ways echoes the federally commissioned photographic archive produced during the Great Depression. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) and Farm Security Administration (FSA) employed photographers like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans to document the Dust Bowl, shoring up support for massive federal spending in response to twined ecological and economic catastrophes. Unlike the profusion of crisis imagery filling our feeds today, these photographs were produced at the service of a specific political project; they elicited sympathetic emotional responses to rural poverty during the Great Depression, and constructed a collective vision of U.S. national identity—one that was rural and white.[8] Although they lack explicit curation by the state, today’s ceaseless flow of crisis imagery does similar work in managing public feelings around disaster. These images clog our feeds, routinely instigating feelings of shock and panic, suggesting inevitability, and endorsing a decidedly negative forecast. Imposing narrow subjectivities of either victim or voyeur, crisis imagery undermines solidarity. In the absence of substantive political commitments, the visual spectacle of crisis can only serve to immobilize and further entrench the status quo. As anthropologist Joseph Masco reminds us, “crisis talk without the commitment to revolution becomes counterrevolutionary.”[9]

We are beyond a point of changing hearts and minds: we have overshot awareness and landed in a realm of anesthetizing overwhelm. At a time when ever-circulating crisis imagery works to diffuse and deflate movements for collective liberation, art and criticism are particularly important in reclaiming attention and redirecting action. I am not speaking of didactic, utilitarian climate art that sighs, if only they knew. Rather, I am interested in art that manipulates and digests the archive of climate crisis images, art that invites new affective attachments and modes of thought altogether. A novel aesthetic approach to climate change—one that is more about feeling, more about ways of being in a precarious world—is essential.

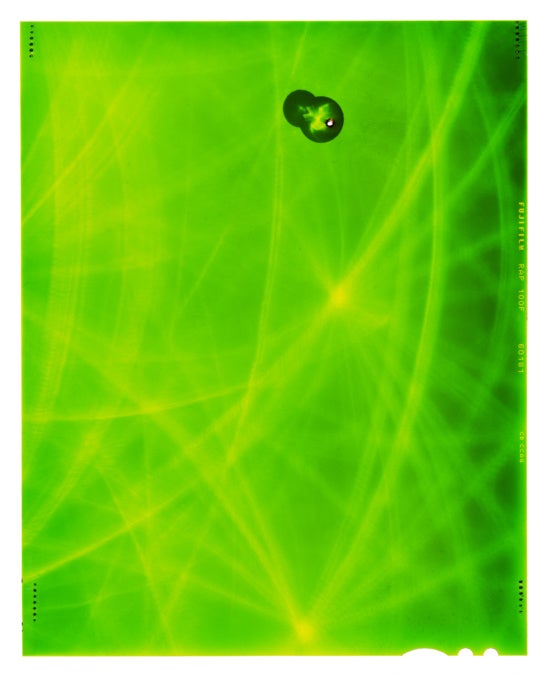

Anastasia Samoylova’s collection of work FloodZone insists on a different pace for picturing and processing climate change. While borrowing subject matter and many formal sensibilities from conventional crisis images, these photographs produce a sense of suspension and stillness. They generate distinct affective resonances—they are dense and slow; their force accumulates in the process of viewing. They are incompatible with the breakneck speed of crisis; unfit for frictionless circulation.

The photographs of FloodZone live in the strange temporality of climate change itself, already catastrophic and suffused in a subtle anticipatory dread. They are uncanny, spatially and affectively weird. They borrow a saccharine palate that evokes a Miami both paradisiacal and sinister; they are often defined by claustrophobic and confusing constructions. And these photographs are insistently gorgeous—rich and meticulously composed. Samoylova’s photographs are generatively unsettling, offering a respite from the deluge of crisis imagery that deadens our senses.

While Samoylova plays on the conventions of crisis photography to produce novel affective trajectories, Margo Wolowiec uses the archive itself as raw material. In Still Water, Circling Palms, Wolowiec collages digital imagery depicting climate disasters—often sourced from Instagram—into densely woven textiles. Distortion is a key strategy here: rendering easily readable images illegible, Wolowiec disrupts the conventional pace of viewership, leaving things unresolved and uncertain. The artist intervenes on an otherwise unmitigated flood of crisis imagery, imposing authorship and insisting on materiality. These are works that have been intentionally brought into the world, not images that are incidentally in it. They are all about surface and texture, about rerouting our conventional mode of looking. In radically transforming an overabundance of climate crisis photographs, Wolowiec invites us to attune differently to this imagery, opening up new modes of thought and feeling around precarious ecologies.

Abstraction proves to be another effective counter to the overwhelm of crisis aesthetics. Torkwase Dyson’s 2020 exhibition Black Compositional Thought (15 Paintings for the Plantationocene) at the New Orleans Museum of Art offers up liberatory modes of thinking about space and precarity. Beyond wearing on our bodies and minds, crisis imagery erases the highly variegated impacts—and historicity—of environmental harms. Opposing theorizations of the Anthropocene that flatten climate crisis as something equally and collectively felt, this body of work expands and specifies Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing’s notion of a Plantationocene[12]. Dyson’s use of the term makes explicit the rootedness of ecological precarity in histories of chattel slavery and settler colonialism in the South, of boundless extraction and exploitation of Black lives and labor. Transcending Haraway and Tsing’s preoccupations with the instrumentalization of nature in plantation logics, Dyson’s work builds out new idioms for thinking through the ecologically deleterious effects of racial capitalism towards what she calls livable geographies. Dyson explains,

“The absence of black labor politics in relationship to natural resources and early forms of architecture, agriculture, and engineering is an abstraction and continues to induce already harsh vulnerability through further erasure. Abstract drawing enables a pointed discussion of these structural histories and our participation in them. It can also prepare our minds to compose with space and materiality that will define our future.”[13]

This work is formally striking—highly geometric and architectural in quality. These paintings feel bodily and tactile; they build out new terms by which we might engage and imagine through our disastrous present. Dyson is explicit about her aim of transforming environments and social arrangements. These works have a clear political project: Black spatial justice.

As Dyson’s work makes clear, we are beyond crisis in the South. The ever-present legacies of settler colonialism and chattel slavery make clear that our troubles are not located in an indeterminate future, but thoroughly suffuse our past and contemporary everyday. In a region where life has long flourished at the edges of disastrous social and political systems, the prevailing aesthetic approach to climate change rings particularly hollow.

Hypersaturated with climate crisis images to the point of numbness, I want art that is multisensorial, haptic, bodily. I want art that unsettles, queers, redirects. Dyson, Samoylova, and Wolowiec—among others—furnish us with ways of thinking and feeling our way to other political, social, and ecological arrangements. Variously hacking, appropriating, and refusing the dehumanizing circuitry of crisis pictures, these artists build an altogether different approach. Another climate aesthetic emerges: one that is liveable, spacious, embodied, slow.

Can you feel it?

[1] See Jess Bidgood, “North Carolina, Still Reeling from Hurricane Matthew, Stares at Irma,” New York Times, September 8, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/08/us/north-carolina-hurricane-rebuild.html

[2] Frances Stead Sellers, “Hurricane Florence set at least 28 flood records, according to new USGS report,” Washington Post, November 13, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/hurricane-florence-set-at-least-28-flood-records-according-to-new-usgs-report/2018/11/13/6e23b922-e766-11e8-a939-9469f1166f9d_story.html

[3] Glenn Thursh and Kendra Pierre-Louis, “Florence’s Floodwaters Breach Defenses at Duke Energy Plant, Sending Toxic Coal Ash Into River,” New York Times, September 21, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/21/climate/florences-floodwaters-breach-defenses-at-power-plant-prompting-shutdown.html

[4] Danielle Purifoy, “The Water Next Time?” Scalawag, October 10, 2018, https://scalawagmagazine.org/2018/10/princeville-flooding/.

[5] Image sourced from PBS Newshour.

[6] See Lauren Berlant’s Cruel Optimism (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, October 2011).

[7] See Rob Nixon’s Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2013).

[8] Sarah Boxer, “White Washing the Great Depression,” The Atlantic, December 2020.

[9] Joseph Masco, “The Crisis in Crisis,” Current Anthropology 58, supplement 15 (February 2017): S65–S76.

[10] Sourced from photographer’s website.

[11] Sourced from the Jessica Silverman Gallery.

[12] Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing, “Reflections on the Plantationocene: A Conversation with Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing,” moderated by Gregg Mitman, Edge Effects, June 18, 2019, https://edgeeffects.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/PlantationoceneReflections_Haraway_Tsing.pdf.

[13] Torkwase Dyson, “Black Interiority: Notes on Architecture, Infrastructure, Environmental Justice, and Abstract Drawing,” Pelican Bomb, January 9, 2017, http://pelicanbomb.com/art-review/2017/black-interiority-notes-on-architecture-infrastructure-environmental-justice-and-abstract-drawing.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series on Nodes and Networks.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2021 here.