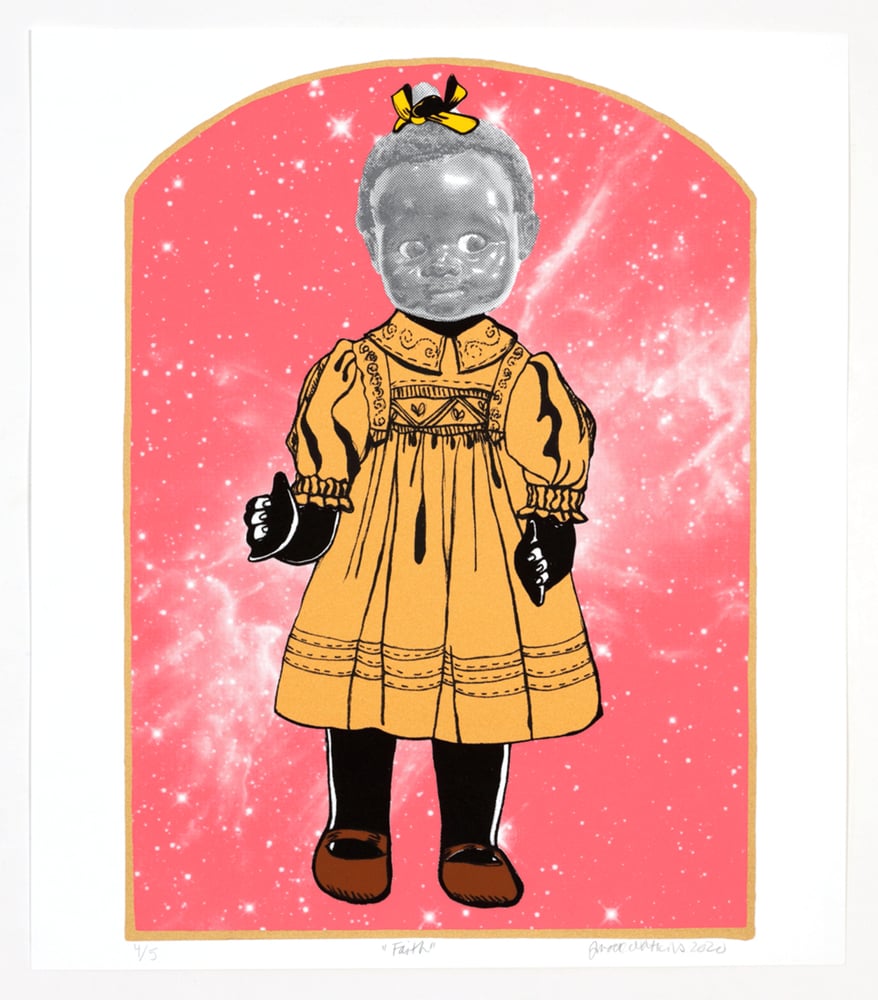

Jennifer Mack-Watkins printed doll figures celebrate Black beauty and creativity while utilizing the process of printmaking as means of teaching and confronting history. These doll prints are featured in her recent exhibition: Children of The Sun at the Brattleboro Museum and Art Center. I sat down to interview Mack-Watkins, an artist and educator, to discuss her process, life in quarantine, and the power of representation. Her work explores themes of resilience, play, motherhood, untold histories, and imagination. As she discussed her work, I envisioned her doll figures bookending Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. Pecola, the central character in The Bluest Eye absorbed messages of assimilation and anti-Blackness. She desperately needed Mack-Watkins’ dolls and inclusive imagination.

Chenoa Baker: How did the pandemic affect art-making?

Jennifer Mack-Watkins: Prior to COVID-19, I juggled openings and lectures to promote my work and support other artists. The pandemic revealed what’s important. At the beginning of the pandemic, my son was three months old. I had him December 2019, then went on maternity leave. The joys of my life, like having and interacting with children, inspired my work.

Children are a common theme because I am an educator. I add to my artistic repertoire by sharing what brings me joy. Who doesn’t feel joy when they see a child laugh, play, or imagine? Children have innate joy; I want the adult audience, of my exhibition, to rediscover this part of themselves and approach the work with joy.

CB: What compels you to depict historical subject matter?

M-W: History repeats; you can’t overlook it and act like it hasn’t happened. I add history into my compositional structures to understand present-day and the past. The present is the conflict of past and present; printmaking merges them to tell a narrative as a visual report. As a printmaker, if I combine layers of textures and colors. Layering overtime shows play: not being confined to one style. I researched in archives and found common themes in the history of different states. We should never take someone else’s word for our history but research our histories for ourselves.

CB: What drew you to The Brownies’ Book: A Monthly Magazine for Children of the Sun by WEB Dubois?

M-W: When I prepared for the Race and Revolution: Reimagining Monuments (2019) exhibition at the Old Stone House in Brooklyn, I searched for positive representations of children within New York history. I revisited The Brownies’ Book when David Ferreira, a guest curator at the Brattleboro Museum, sought me out for a solo show. The Brownies’ Book, which came out in the ‘20s, gave hope to children. Dubois responded to the race riots then by educating and uplifting Black children through games, puzzles, and illustrations. Families sent photographs of their children dressed in white for the publication.

From there, I incorporated Vermont history by sharing information about the poet Daisy Turner (1883-1988) from the Vermont Folk Center. After listening to recorded audio by Jane C. Beck, it confirmed that children would be my focus. As a child, Turner’s teacher assigned her a poem recitation while carrying a Black doll (in stereotypical attire); instead, she interceded for the doll by reciting her own poem.

CB: Your work connects to The Bluest Eye by reimagining childhood and dolls.

M-W: I read The Bluest Eye in middle school and felt empathetic towards the characters because of what they wanted to be. Assimilation is horrible. Educating children about themselves by changing curriculums and history books ensures they won’t feel like characters in the Bluest Eye.

Growing up in the South, I played with dolls; dolls that didn’t look like me. I needed something I could imagine myself in so I designed my own paper dolls. I knew, then, that play was important; imagination is what we had, since there wasn’t much to do. In lieu of Black history, we read Tar Baby—a poor representation of African Americans—and only commemorated Black history during Black History Month.

For me, dolls are a coming-of-age memory. I played with clothing options for dolls because outfits embody who they become in that moment. When I first made the dolls in this series, I had my four-year-old daughter paint on copies of my sketches to observe how she sees them. The dolls show that children are represented in many ways through exhibitions and literature. Dolls become anything you want it to be, which exudes the act of play.

Everyone should have opportunities to feel like they can go the moon. I mean space in the non-literal sense, unlike Mae Jemison, by imagining infinite possibilities. The future is bright and open. Space, a mysterious place, is undefined; when I include galaxies in my work, it shows the child’s limitless potential. It references Reading Rainbow when a book opened, butterflies came out saying “butterfly in the sky.” It made literature look fun. My work responds to Black literary representation.

Children of the Sun is on view at Brattleboro Museum and Art Center in Brattleboro, Vermont until June 13, 2021.