“I wanted people to walk into our home and understand immediately that this was going to be a different kind of experience,” says Tim Schrager, Atlanta art collector and one of the principals of Perennial Properties, Inc., an Atlanta-based mixed-use commercial development firm. Objective achieved. Visitors to the Schragers’ gracious home immediately encounter Fascist Fruit Boys (2010), a raucous multifigured sculpture of rude boys with heads, eyes, noses, and hands made to resemble pumpkins, squash, onions, bananas, etc., laying siege to a giant scowling cone full of french fries. Is this the story of the good carbohydrates kicking the hell out of bad carbohydrates or a metaphor for fast foodies and mob rule? Actually, artists Shaun Doyle and Mally Mallinson fashioned the poses after images of skinheads and rockers of the late 1960s. Their work is based on “interests in different subcultures, the counterculture, absurdist humor, advertising, social commentary etc.,” explained Mallison in an email. Tim spotted the cheeky wit of the British duo when he was at Art Basel Miami, the one art fair that he visits each year to get an overview of the international art world and connect with art dealers and galleries.

As the collection unfolds in every room, corridor, and stairwell of the home, it is clear that there is more than just visual appeal or art market savvy here. A penchant for artists who are storytellers and an appreciation for works of a multivalent nature is evident, as are an understanding of the art historical context and the conceptual framework. Schrager’s interest in art collecting was stoked by his father, who collected such artists as Minimalist painter Brice Marden. Growing up in Omaha, Nebraska, Schrager remembers that, at first, he thought that a Marden painting with a chalky monochromatic surface and a thin empty border on the bottom was just plain weird, but after the prolonged viewing that living with art allows, he began to appreciate that there was more to it than he initially thought. As a respectful nod to his father’s commitment to Minimalism, part of his collection includes artists who are following in that tradition of reductivism, such as Callum Innes, a Scottish painter of elegant geometries who composes in terms of polarities: additive and subtractive, presence and absence.

A serendipitous occurrence also shaped the collecting practices of father and son, who had parallel transformative experiences in their younger years. Both went on a post-high school trips to Europe, both stood in front of Rembrandt’s masterpiece The Night Watch at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and both credit their love of art from the experience of seeing that painting.

In the mid-’90s, when Tim and Lauren moved into their Buckhead home, the vast empty walls seemed to cry out for art. There are no empty walls now. In addition, sculpture has replaced furniture over the years. The collection is also housed in the offices of Schrager’s company, Perennial Properties—lucky employees—allowing for the rotation of works between home and office. The initial thrust of the collection was emerging artists but Schrager’s growing understanding of the art historical context (influences, schools of thought, how the art connects to a specific period) led him to acquire works of older artists who profoundly influenced and informed the work of younger artists today.

A well thought-out placement of three pieces in the dining room speaks to this aspect of the collection. Dana Schutz’s painting Fan (2010) is flanked on adjacent walls by Peter Saul’s Brush Your Teeth (2003) and Carroll Dunham’s Untitled (2002). Both Saul and Dunham have been key influences on Schutz and the installation allows you to make those connections. Saul’s garish personages emerge from a place where cartoon culture meets surrealism. This sensibility speaks to the heightened color of Schutz’s rambunctious mix of figuration and abstraction in wildly imaginative scenarios. Schutz also follows in Saul’s no-holds-barred approach to subject matter, and both provocateurs are no strangers to the controversies their paintings have engendered. In comparison, Dunham’s painterly storytelling exists in what one writer called “an environment of pathos and psychodrama” as seen in the untitled black and white painting. The imaginary vocabulary of places and persons in Dunham’s painting relates to the bizarro narratives often spun in Schutz’s work.

Another Dunham, titled Peanut Figure (1984), is one of the jewels of the collection. It is a large-scale painting with the trademark blend of abstraction, anthropomorphic forms, and wood-grain patterns Dunham orchestrated in lively paintings in the 1980s, the period when he emerged as one of the leading postmodern artists. A recent Richard Aldrich painting hangs to the right of the Dunham, and a massive Albert Oehlen painting in the same area deserves applause.

Schrager does not shy away from challenging works of a conceptual nature. On a bedroom wall, a series of ten pieces by Gedi Sibony is initially perplexing as they appear to be blank works showing tape and other elements that one would find behind an artwork in a frame. As Schrager explained, the artist “purchased art, which he brought back to his studio, reversed the picture in the frame, and put back together.” In artspeak terms, Sibony is deconstructing the artwork, upending the original function of the art, and repurposing it as the signifier of the artwork you can no longer see. Schrager arcs to the art historical context, “I think it’s coming from Duchamp—it’s a step past putting a toilet on display in a gallery.” Another conceptual piece that is not in a bedroom but could be is Guyton/Walker’s work Canstripe Mint Mattress (2013), a collaboration between Wade Guyton and Kelly Walker. It is a painted mattress that was included in Hamza Walker’s wonderfully titled exhibition “Teen Paranormal Romance,” which appeared in 2015 at Atlanta Contemporary, for which Schrager is Chairman Emeritus. He also serves on the Board of Directors of the High Museum of Art. Supporting the arts in Atlanta is a priority for Schrager. It is, he notes, “a way to give back to the community.” Atlanta artists are also well-represented in his collection, including Joe Camoosa, Craig Drennen, and Dana Haugaard, among others.

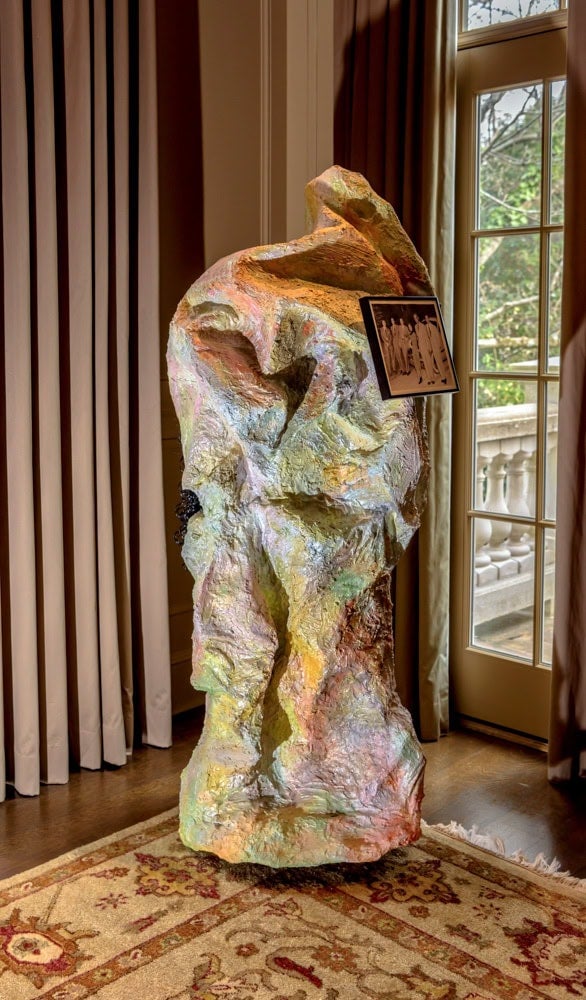

Many works in the collection require a sort of intellectual connect-the-dots from the viewer. These are the kinds of works that draw you in initially because they are dramatic and stunning. But then you ask what’s going on here as the art elicits interpretation. Such is the case with a sculpture by Rachael Harrison, an artist that the Schragers have followed for almost 20 years. Tim describes Harrison as a “really witty, smart artist” who combines sculpture, painting, photography and found objects in inscrutable sculptural installations. Harrison’s mixed-media sculpture Miss Florida (2005) is a vertical, if not phallic, version of a totem structure that looks as if it is in the process of melting. Iridescent surfaces in gradations of warm yellows and blue-greens cover undulating forms, but the party begins when you try to understand the connection between the three found objects attached to different parts of the structure: a photo, a plastic gorilla with long curly locks, and a fake carrot. The vintage photo, given to Harrison by fellow artist Amy Sillman, is a group portrait of Boris Karloff, the boxer Jack Dempsey, other television actors, a Miss Florida and a car dealer to the stars. The piece is housed in the den amid a bevy of such mind-bending works as Dan Attoe’s neon wall piece Loaded, Nailed and Short on Cash, an Alex Hubbard video work and a Peter Saul piece titled The Toilet Leaves the Room.

But there is more to collecting than informed and fearless choices. Collecting in today’s global and exorbitantly priced art market, where works by major artists are often gobbled up by corporate moguls, superstars, sheiks, and “investment” collections with Swiss bank accounts can be a blood sport. Tim has at times found a way around the million-dollar price tags for established and midcareer artists. For example, the market for Saul’s work has been undervalued. Although Saul is the quintessential artists’ artist, he is difficult to pigeonhole art historically. He was a Pop art pioneer without the cool detachment of other Pop artists such as Warhol and Lichtenstein. And Saul, who lived primarily in the San Francisco Bay Area was also erroneously labeled a Chicago Imagist, which adds to the general confusion as to where to situate Saul’s practice. Although early Sauls fetch high prices, the more recent work is in a far less prohibitive price range compared to his contemporaries who emerged in the 1960s.

Another example of art market savvy is the acquisition of a small Mark DiSuvero sculpture, Christread (2002). Schrager knew that when the work of well-known artists come to auction, the hammer price usually far exceeds the estimate. But sometimes they don’t. In this case, patience resulted in the acquisition of a wonderful example of the DiSuvero’s mixed-metal kinetic sculptures.

New collectors can learn much from Schrager. First, a love of art is the best place to start. Next, look at a lot of art. Establish relationships with respected professionals in the field and take a leadership role in your local art scene. And never stop looking and learning.