I’ve seen the most beautiful cities in the sky.

In resonance with our current catastrophic global pandemic, a curatorial trend of revisiting historic mediumistic artists has surfaced. Emergent in the mid-19th century the recognition of mediumistic art practices is widely associated with the Spiritualist movement in Europe where artists including Georgiana Houghton (1814-1884), Hilma af Klint (1862-1944), Madge Gill (1892-1961), and Unica Zurn (1916 – 1970) developed creative practices by channelling the world beyond. Following the destruction of World War I and the mass loss from the 1918 influenza pandemic, Spiritualism offered grief-stricken Europeans a sense of transcendental escapism and a way to communicate with their recently deceased. As we return to exploring these spirited creatives lead by intangible nonhuman powers, Southern artist Minnie Evans (1892-1987) emerges in the dialogue, presenting her own distinct contribution and circumstance to the examination of artists in the realm of mediumship.

The historical and curatorial contexts that have enveloped Evans and her European peers have included the broad circumstances of being a woman and facing the devastation of war. Yet, Minnie Evans’ position as a Southern Black woman in the Jim Crow Era of America sets forth her own complicated experience amid oppression. A critical divergence to consider for Evans in juxtaposition to her European counterparts––whose mediumistic communications were often an alternative to, or in opposition to organized religion––was her devotion to the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). Her historical positioning in America and unwavering faith both distinctly mark her practice in the exploration of 20th-century spiritual artists.

For centuries, characteristics associated with mediumship in women (hearing voices, emotional, erratic behavior) have been deemed “hysterical” and such behavior carries the risk of being institutionalized. Evans’ own visionary experiences were met with trepidation by her family and community, and she encountered accusations of being “crazy” throughout her life. Though fought on foreign grounds, America also faced adverse impacts following World War I. The Black community of the South encountered the harshest realities of these conditions and of those followed by the Great Depression in the 1930s. Specific to Evans’ generation was the severity of the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot. This catastrophic event of a white mob seizing the city resulting in a massacre of African Americans was a turning point in North Carolina history; a terrorizing experience, which profoundly impacted her community towards operating with heightened reservation.

Evans strong Christian faith, relationship with God, and biblical knowledge were integral to her visions and creative practice. Post-emancipation and amid severe segregation in the South, the Black Church became a seminal autonomous organization for African Americans. Within this spiritual and social structuring, Evans was a part of and astutely dedicated to the AME. The deep connection of Evans’ mediumship to her Christian faith, likely emboldened her (personal/transcendental) experience, and the contextualization of her visions within the Black Church would have created a level of security for these explorations in the only space protected by her community.

I had dreams of all old prophets

Evans did not begin regularly drawing until later in life; however, her visions started at a very young age. Encounters with prophets and angels in dreams and visions occurred from age three or four. Born in Pender County, North Carolina in 1892, Evans’ family was of African Trinidadian descent and formerly enslaved in the South and before in Trinidad. She was raised primarily by her grandmother, who explained that her vivid dreams were a spirit calling to her. Evans recalled telling fellow children of seeing elephants dancing around the moon, as well as feeling tired at school because she was exhausted by her own dreams. Her extensive recollected visions teetered between joyous and severe. She referenced in childhood, awakening in a cemetery after being carried by prophets in her sleep, and in adulthood, witnessing a wedding party of ants while inside a log. At sixteen, Evans married and went on to have three sons. Her husband, Julius, was supportive of Evans, even to a metaphysical level, with her stating that the tormenting in her dreams stopped when she married.

Evans completed her first automatic drawings harnessed by intangible energy in 1935. As she recalled, it was Good Friday and the day her grandmother died. She had just completed writing her grocery list when her hand continued onto a new page, drawing intuitively with the pencil. The following day, she finished a second page and then casually stashed them in a magazine. Five years later, having not drawn further, Evans took a stack of trash (including the magazine) outside and threw it into a fire. She explained that everything burned except for those two drawings which slipped out from between the magazine pages, confronting her with the forgotten creations. Harnessed by her visions and led by the messages, from that day in 1940, she began drawing regularly as an order from God. The mounting tenacity of her visions also peaked around this time, aligning the pinnacle of their intensity with drawing regularly.

In 1944, a faith healer/psychic named Madam Tula worked from a five-and-dime store in Wilmington. A friend of Evans’ recommended she visit Tula in regard to her drawings. On her first visit, Tula greeted Evans by name, looked “through” her and said: “You want to paint”. Evans was instructed to retrieve her drawings, and the following day she returned with her collection of 144 compositions. Tula proclaimed in reference to Evans’ initial two drawings: ”These two pictures have control in the whole world.” She informed Evans that the world would know about her and that her drawings were connected to the current World War. Specifically, Tula spoke of l a future drawing’s relationship to an “invasion”. Evans later thought this could have been in reference to the 1945 atomic bombing of Japan. Attributed to a higher power and responsibility to draw, at times Evans was affected physically and emotionally. She recalled feeling “mixed-up”: not able to function properly nor complete her daily tasks adequately. Subsequent to her visit to Tula, Evans said something spoke to her, stating: “Why don’t you draw or die?” She then worked feverishly without food or water on a drawing. Following family concerns, she took a break to sleep, but with a loud boom (that only she heard) in the middle of the night, she arose to finish what she considered to be the drawing predicted by Tula.

Though supportive, Julius struggled at times with her proclaimed visions and steadfast commitment to drawing. He and Evans’ mother would accuse her of being “crazy”, or more acutely, worry that others would think she was “crazy”. On at least one occasion, Julius sought advice from their local pastor with concerns Minnie was acting “funny” and might need to be admitted to an asylum. The pastor’s response to his apprehension was to leave Evans to proceed on her path, affirming she was following God’s plan.

My work is just as strange to me as it is to anyone else.

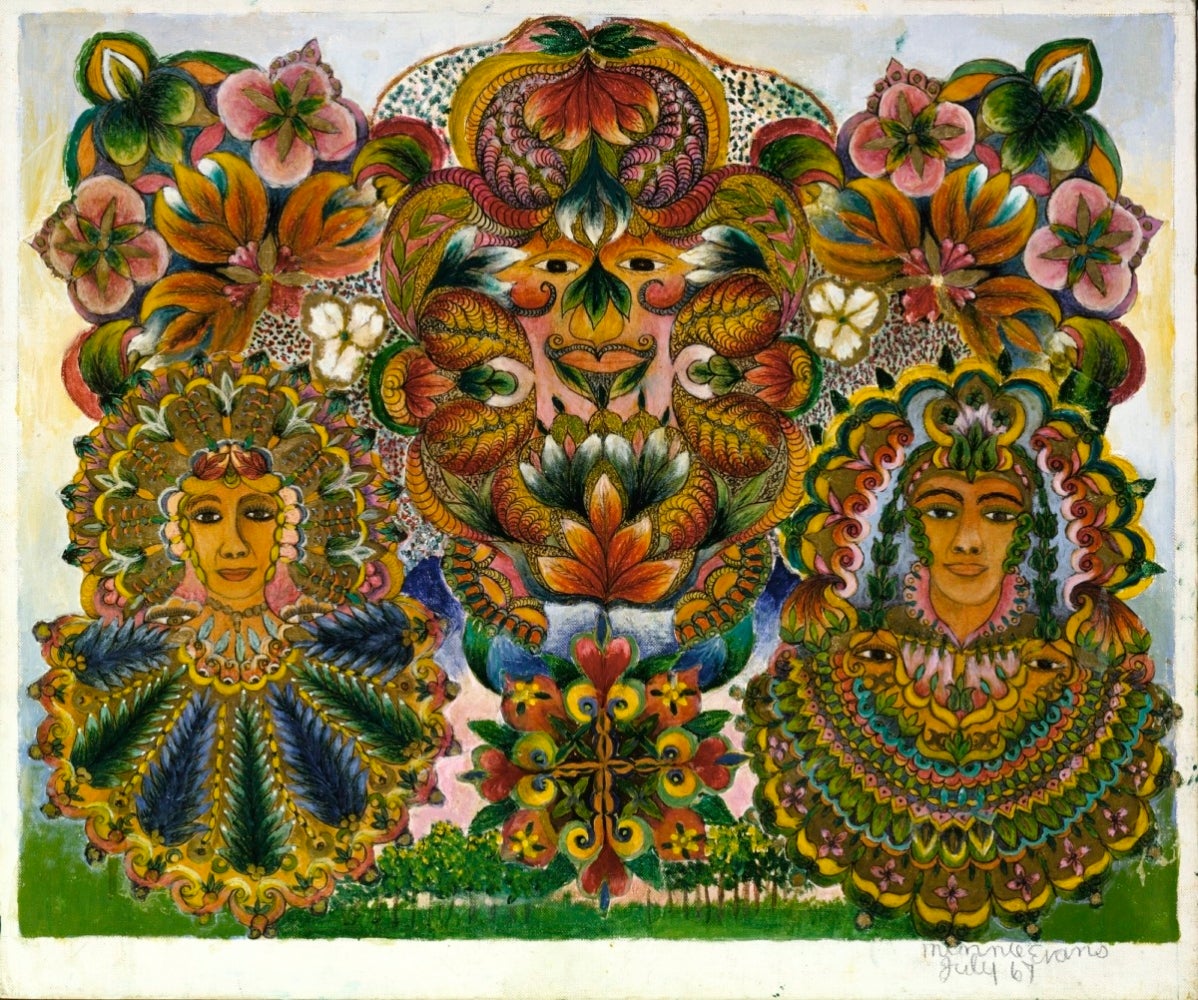

Aligned with her more complex aesthetic developed mid-century, from 1948 to 1974 much of Evans’ oeuvre was produced at Airlie Gardens on the Pembroke Estate, where she worked as the gardens’ gatekeeper. While conceptually informed by her intangible influences of God and visions, the surroundings of Airlie Gardens appear to have abundantly transpired in her compositions. Drawing daily onsite for over 25 years, her exuberant oeuvre of this period is inhabited with lush botanicals, blooming flowers and colourful butterfly-like patterns creating Gardens of Paradise with symmetrical framing and kaleidoscopic radiation. She had been working on the estate since 1918, initially as a domestic servant for the Estate, where decorative elements from Persian carpets to the intricate designs of European porcelains seemingly also informed her drawn visuals. Evans spoke fluidly of how her drawings were instinctual and influenced by her otherworldly encounters, but visually, not direct recreations or diagrammatic of her dreams. Instead, Evans’ earthly surroundings at Airlie Gardens became metaphorical visual vocabulary for the symbolism of her religious visions.

While the position was taxing, working seven days a week, her position as a Gatekeeper also became an inadvertently mixed-race environment which exposed her drawings to a white audience. Selling her drawings to visitors of Airlie Gardens provided a pathway to exposure to a wider audience, exhibited for the first time in 1961 at the Little Gallery in Wilmington. Her work on display at Airlie Gardens also led to Nina Howell Starr becoming aware of her work. Starr was a life-long advocate of Evans and first presented her work to a New York audience in 1966. This was followed by a 1969 feature on Evans in Newsweek and a solo exhibition at the Whitney in 1975.

In juxtaposition to the admiration she gained on a national level, Evans discussed that following her success, there was an apprehensive tension between her and members of her Black community in relation to the attention she received from white people.

They are all angels and all are white.

Omnipresent throughout her oeuvre are eyes staring intensely back at Evans, or whoever encounters her work. The eyes and overall compositions evoke a palpable sense of God’s presence. The faces beyond the eyes appear as angels, mystics, prophets, and selectively likely God themself. Evans’ lack of representation of figures with dark skin in her depiction of faces has inspired discursive contention. She was asked about this in 1971 and explained that when she sees people in heaven they are “all angels and all white”. She later discussed, on a more process-based level, that the color of her drawn faces is due to the crayon she uses and a method of scraping away the mark. She further commented when asked if the figures were “white”: “I don’t think it would make a difference because white isn’t goin’ to make me what I am.” This response could be considered very aligned with the totality of Evans’ expansive experience that went beyond her material existence on earth, rendering it plausible that she was not actively considering race when drawing faces.

Evans’ often had a copy of the Kings James Bible with her onsite at Airlie Gardens and was recognized for her deep connection with the book. In her practice, aesthetic decisions reflect direct and indirect biblical influences. Furthermore, specific visions appear to parallel biblical verses. In one series of visions, Evans was lying in bed when a wreath appeared with a great light behind it. These visions relate to Ezekiel, the Old Testament book recording six visions by the Prophet Ezekiel, a priest exiled to Babylon. The specific appearance of a circular form in the sky mimics the prophet’s inaugural vision of chariot wheels. The conjured visual of the wreath’s green leaves, backlit by a wondrous light, is evocative of many of her compositions wherein a mystical space is created, spiralling between land, sky and heaven. During this vision, God told her this very light shall shine all around her.

The story of Noah’s Ark in Genesis also played an essential role in Evans’ visual affinity for rainbows. She referred to the act of God sending Noah a rainbow after the flood and further explained that she believed heaven would be full of rainbows. The book of Revelations was also particularly significant to her. Egyptian motifs are abundant amongst her symbols and imagery, a potential reflection of her contemporaneous Black community’s connection with the narrative of the emancipation of the Israelites in Exodus.

And then I went out on the front porch. Everything I looked at was rainbow.

Channelling her multifaceted relationship with the higher power from within the AME Church provided a guarded context for her spiritual messages through prayer, visions, dreams and her intuitively led drawings to develop and burgeon. With the safe space provided by the Black Church and the physical space of Airlie Gardens, Evans’ oeuvre gained a diverse following and recognition amid the oppression of the Jim Crow South. Her oeuvre examined within the curatorial context of mediumism allows for a wider totality of spiritually led practices to be understood. Evans remembered over a dozen occasions seeing “the most beautiful cities in the sky”. Her compositions do not allude to built landscapes, but many give the sense of firmament, mythical existence and faithful belief of nonhuman presence on the horizon.

The work of Minnie Evans is currently part of The Milk of Dreams curated by Cecilia Alemani at the 2022 Venice Biennale through November 2022.

Unless noted otherwise, all quotes are by Minnie Evans sourced from the Nina Howell Starr papers, transcribed by the Smithsonian Institution.

Become a member or make a tax-deductible donation below.