Born and raised in Chattanooga, Bret Wood is an Atlanta-based independent filmmaker who has produced and directed several feature films and shorts, many of which explore morality, transgressive behavior, and social taboos. His new feature The Unwanted is a contemporary interpretation of Carmilla, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 gothic novella. I first learned of Bret in 1988, when I worked in the non-theatrical film distribution market and he was employed by Kino International, a distributer of silent and classic films. Bret is now vice president and producer of special projects at Kino Lorber, which entails curating titles for Blu-Ray/DVD releases and supervising the digital restoration. In addition to a full time occupation, he continues to produce his own film projects. In 2003, he released his first independent documentary, Hell’s Highway: The True Story of Highway Safety Films, a survey of the infamous driver’s education films (produced between 1959 and 1979) and the people who made them.

I have followed his work ever since and continue to be impressed with the thought-provoking nature and personal aesthetic of each new film. Among them are Psychopathia Sexualis (2006), a dramatization of selected case histories from Krafft-Ebing’s Victorian-era study of sexual perversity, and The Little Death (2010), adapted from Frank Wedekind’s The Death and the Devil and Anton Chekhov’s A Nervous Breakdown. The following interview was conducted at Bret’s home in College Park, Georgia, where he lives with his wife and son.

Jeff Stafford: What attracted you to Le Fanu’s Carmilla and what are you bringing to it that hasn’t been explored in other film adaptations?

Bret Wood: I saw that the story could be told in a totally different way. It’s about the growing suspicion around this woman who is a guest in someone’s home … that she may be a vampire. The father’s suspicions are fueled by other people in the village, who have much stronger superstitions about vampires. So they plant these thoughts in his head that eventually lead him to believe that this woman should be killed. And it occurred to me, what if she is not a vampire? What if she is this woman who gets stranded in this small town that’s filled with superstitious people, and she has an affair with the man’s daughter? It puts her in a very vulnerable position. The fact is, if someone thinks you’re a vampire, it doesn’t matter whether you’re a vampire or not, because they might kill you. If someone feels they are righteous and they are doing something in the name of God, then they feel totally justified in doing it even if it’s murder.

Stafford: Tell me about your casting process for The Unwanted.

Wood: We did a casting call, but it wasn’t open to everyone. We invited people who I had worked with or I’d seen on stage in Atlanta. I didn’t precast anyone, and the people who ended up getting the roles were people I had never worked with before. Christen [Orr], who plays Carmilla, I had seen on stage in Spring Awakening. An actor I have worked with in the past, Clifton Guterman, recommended a few people because I wanted to get outside of my regular group and because it’s sensitive material. I’m always very cautious about that. I usually don’t have open casting calls because I want to avoid the awkwardness of explaining what the movie’s about and having someone be uncomfortable … and maybe not wanting to get the part because of what the role may entail.

Stafford: The Unwanted was certainly a different kind of role for William[Bill] Katt.

Wood: When our executive producer, Eric Wilkinson, recommended him, I was resistant. I loved Bill’s work, especially in Carrie, but I worried about having The Greatest American Hero [of the 1981 television series] playing the heavy. I didn’t want it to come off as campy. But he played a character which to my mind is totally different from anything he’s played, and he was completely serious and dedicated to the project. He lost himself in the role and, I think, delivered a very solid performance.

He also gave a lot of feedback about the script. In fact, he felt that the way his character was written was too unsympathetic, that from the very beginning we know he’s a villain, and we don’t see any affection between him and the daughter. Bill said, “Why don’t you have a scene where he and the daughter are doing something together … anything, to show that they are bonding?” That was how the scene evolved of him teaching Laura how to ride a horse. It just so happened that one of the locations we were using was a horse farm and Hannah [Fierman] said, “I can ride a horse.” So I wrote it into the script.

Stafford: The sex scenes in The Unwanted must have been daunting for the actors. How do you gain their trust and confidence before filming such scenes?

Wood: Actors are very tuned in to the behavior of the director on the set. So if I am uncertain or shy about shooting a scene, then they are going to become nervous or shy. But if I’m very confident and explicit in explaining what I want, they’ll be just as focused and direct in what they’re doing. It’s one of the most valuable lessons actors have taught me. I like to think that the sexual content of my films is not gratuitous. It’s often the substance of the movie. Recognizing this, the actors understand that we can’t just tiptoe around it.

For The Unwanted, you can’t be coy about what’s going on between the two women because it’s very much about their physical relationship. If you cloak it in mystery and shadow, you don’t know what’s going on in the movie. So it’s important that we know exactly what they’re doing. We have to know when they’re cutting and drinking blood and when they’re having sex.

Stafford: The blood rituals reminded me of some case histories in your film Psychopathia Sexualis.

Wood: It’s an intimate act. It’s an exchange of a bodily fluid, but it sort of skirts the moral issue. If someone feels like it’s technically wrong to have sex with someone, they might think, “but I can drink their blood— that’s not having sex.” So it becomes a transgressive, rebellious act that is technically non-sexual but is incredibly sexual. You get a lot of that in the book, in a lot of the case studies. That’s probably why I came back to it for The Unwanted. Vampirism is really about sex because it’s about someone being seduced by this outsider, exchanging bodily fluids, and being emotionally altered as a result. And there’s almost always a father figure trying to protect the innocent daughter from “corruptions.”

Stafford: Do you allow for improvisation from actors or change scenes and dialogue once rehearsal begins?

Wood: With The Unwanted, more so than any in the past, I worked with actors in advance of shooting the movie. It’s more like workshopping than rehearsal. In fact, it was with two actors who are not actually in the film: Katie Graham and Jen Bates. We had been involved in a local filmmaking program called Sessions and decided we would get together and workshop this script. We’d meet at someone’s house, first reading it and discussing it, and then actually performing it. It was hugely helpful because it gave me actor feedback—what’s working, what’s not working. It made us see what’s really going on in the scene.

For the first time, that was purely for the exploration of the script and the characters and deciding what a character is like. Because I wasn’t even sure of the Laura character—whether she’s this Goth girl or totally naive and innocent. You don’t really know what your movie is going to feel like until you hear actors say the lines. And the table read for me is the moment when you realize if this script is really worth pursuing. In order for your movie to be good, you want people to bring things to the table and you want your vision to evolve from the input of other people. It’s great when it works because suddenly the script you have is better than you thought it was.

Stafford: How are you going to promote The Unwanted—as a horror film, psychological drama, or erotic thriller?

Wood: I’m concerned about that, because I had originally planned to market it as a horror film. But when you watch the movie, it’s such low-key horror that it’s almost false advertising, especially in today’s environment, because most horror festivals are all about shock and gore and extremity. So I’m kind of testing the waters to see what type of film people think it is, and hope that they will recognize it as an interesting independent film. It could fit into no one’s niche or it could fit into everyone’s niche because it’s got horror, it’s got erotica, it’s got gay/lesbian themes, it’s got a little something for everyone but it’s not enough of any one thing to have a predefined space in the marketplace. I tend to make movies that don’t fall into a clear genre, which I love but at the same time it’s a real drawback.

Stafford: As someone who grew up in Chattanooga, do you see any regional influences in your work?

Wood: I don’t think so. When I tell people about The Unwanted, I sometimes jokingly call it “a southern gothic lesbian vampire movie.” The Unwanted is set in the South, but I don’t really feel that it’s Southern other than the fact that there is a character with a kind of Southern mentality – the father. The thing that really shaped me the most was being raised in a culture in which movies were frowned upon. Being of a Pentecostal religious background, if I went to a movie I wasn’t supposed to talk to anyone about it at church. My parents let me see movies, but we weren’t really supposed to talk about them because movies were looked upon as inherently immoral. I think one reason I was so interested in movies is because they were taboo.

Stafford: You once said in an interview that you “wanted to make something that tapped into your darkest fears and desires.” Can you elaborate?

Wood: You know there’s no point in making a movie unless it is deeply personal and reveals something about yourself you wouldn’t otherwise share. It’s like you are erecting a monument to yourself but in a sort of a cryptic way. You want people to know what you’re like without providing any of the facts. It’s not too literal because, even in The Unwanted, I’m very much this character and I’m very much that character. In The Little Death, I’m very much both characters, even though they’re opposites. Sides of my personality are reflected in different characters. It’s good to have conflict within yourself. It’s a way to work through your uncertainties. I feel like if I went to a psychiatrist or psychotherapist, I wouldn’t make movies. This is kind of a process of exploring who I am, and it probably satisfies the same need that some people have by seeing a therapist.

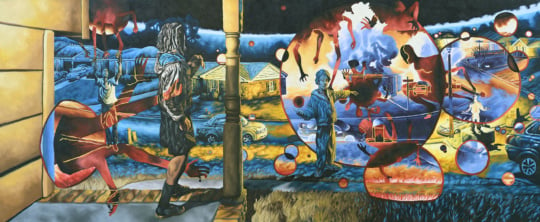

My movies seem to be about people wrestling with their own repression and also fighting against the oppression that’s been imposed by others. None of the movies have a fixed message. I don’t think life has fixed messages. I don’t think I can teach you a lesson because there are no absolutes, especially in human relationships. I like for my movies to be like a Rorschach test, so you see something in it depending on who you are.

Jeff Stafford is an Atlanta-based arts and lifestyle writer.