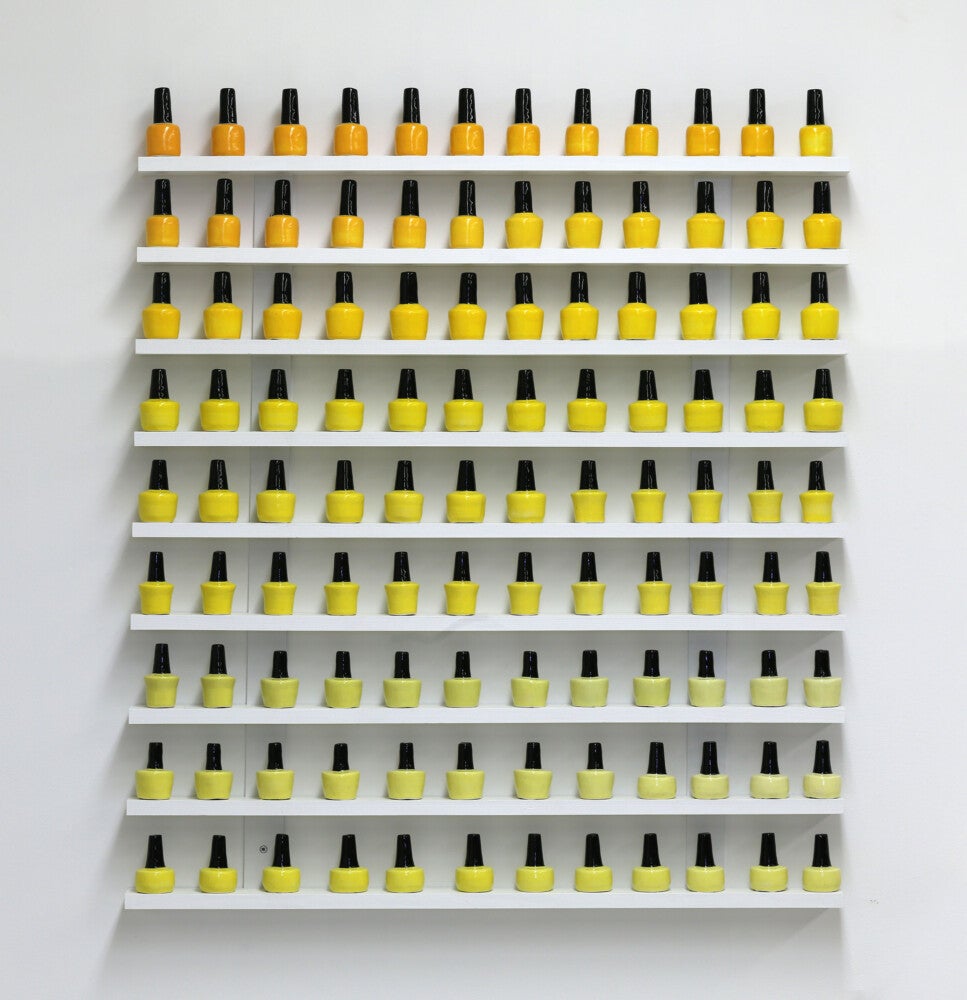

Christian Dinh’s artistic practice is driven by a need to remember—both his own past and that of a broader Vietnamese America. Through sculptural works that celebrate the sights and sounds of social hubs created by and for the Vietnamese community, Dinh archives a generation of diaspora and working-class visions of success.

Dinh began the Nail Salon series, in which each work centers a pair of cast porcelain hands resting upon a silk pillow, in 2020. Based on the plastic display common in nail salons, the fine porcelain hands, with their long, elegant nails and smooth unblemished skin, become symbols of veneration of the larger nail industry. The vast majority of nail salons in the U.S. today are owned and staffed by Vietnamese workers, a trend often credited to having started with a 1975 job training program that connected about twenty Vietnamese refugee women with manicurist positions in nail salons in California.1 “The salons became a sort of beacon where incoming immigrants and refugees could find work, as well as security and care,” remarks Dinh. “Even if you didn’t work in the salon, it just was so embedded in the culture.” In addition, each work’s silk pillow alludes to the many Vietnamese seamstresses and tailors in the U.S., a reflection of the major garment and textile industry in Vietnam.

Dinh spent the early years of his childhood in St. Petersburg, Florida, home of a vibrant Vietnamese population, growing up in a household that included his grandparents, aunts, and uncles, just down the street from the local Catholic church everyone attended. The artwork MÔT HAI BA DZÔ! (2022), its title translating as “1, 2, 3, drink!,” is based on Dinh’s memories of the parties his grandparents hosted when he was a child. Both porcelain hands in the work are lined with designs from mahjong tiles. Dinh fondly recalls watching family and friends in the midst of a hand: “It’s so vivid—the intense, silent, almost meditative gambling as they went through the rhythms of the game. The clinking and shuffling of the tiles.” Karaoke was another classic party activity; Dinh pulls the kitschy typeface used on each hand from the karaoke machine. “It’s this idea of celebrating just to celebrate, creating occasions to join together,” he says.

A series of family moves during Dinh’s adolescence—to towns with much smaller populations of Asian Americans—led to the artist’s sense of detachment from his Vietnamese identity amid navigating casual racism and pressure to assimilate. As an undergraduate at the University of Western Florida, Pensacola, he began the work of actively reconnecting with his grandparents and reclaiming his heritage. There, Dinh also took his first ceramics class. The artist credits mentors Dryden Wells and Andy Moon for their “generous and insightful teachings in the medium…sharing the philosophy of finding the beauty in multiplicity…[and] understanding the subtleties of surface.” Following graduation, Dinh worked as a production potter for two years—“it’s brutal work”—honing his techniques using stark white porcelain and vibrant glazes. All the while Dinh was thinking through the material history of “fine china”—how it’s been used and traded globally—which led him to questions of displacement and authenticity.

When Dinh moved to New Orleans in 2018, he was struck by the city’s familiarity. “One of the main reasons I started making art again was the Vietnamese American community in the city…I started spending time in New Orleans East and going to Lunar New Year celebrations…I just felt that ease of fitting in.” Dinh did a deep dive into the history of Vietnamese settlement in the U.S. during and after the Vietnam War and, while a student in the MFA program at Tulane University, the Nail Salon series began to take shape. The works appropriate the materials and everyday visuals that define Vietnamese American culture as a means to recognize the efforts taken to build community and, more personally, to commemorate the generation of the diaspora in which Dinh grew up. In one of the earliest pieces, Aroma (2020), Dinh pays homage to the Aroma-brand rice cooker—a dependable, familiar, functional staple in many Asian American households which, at its cheapest, can be purchased for a mere $19.99.

Dinh describes a later Nail Salon iteration, In the mud, what is more beautiful than the lotus? (2022), as a turning point in the series, one that draws parallels between the river delta cultures of the Mississippi and the Mekong. Taking the work’s title from a Vietnamese ca dao, meaning song without music, Dinh lines the inside of each forearm with a poem:

Trong đầm gì đẹp bằng sen

Lá xanh bông trắng lại chen nhụy vàng

Nhụy vàng bông trắng lá xanh

Gần bùn mà chẳng hôi tanh mùi bùn

In the mud, what is more beautiful than a lotus?

Green leaves, white flower covers a yellow center

Yellow center, white flower, green leaves

Close to mud but never smells as mud

(transcription by Selina McKane)

As the lotus, the national flower of Vietnam, grows out of the muddy waters of low flood plains, it symbolizes the resilience and longevity of the Vietnamese people. The lotus’s American counterpart can be found throughout the backwaters of the Mississippi River, and calls to mind the Vietnamese American culture that emerged in the subtropical landscape of New Orleans—unexpected, beautiful, strong.

Dinh finishes his ceramic hands with a pearlescent glaze, a reference to another beauty hidden beneath the water. Pearls are significant to both regions: mother-of-pearl inlay is a traditional art form in Vietnam, one Dinh would often encounter in the decor of homes and restaurants, and the pearl necklace is iconic to archetypal fashion of the American South. When discussing this intertwining of mud, Dinh considers the role of ceramics: “So many creation myths stem from the clay of the earth…[the making of] ceramics is a relatively ritualistic practice with so many steps that you treat preciously. The routines of washing and prepping the clay, building clay bodies, cleansing and finishing, putting them into fire for creation…” The intentionality behind Dinh’s practice and his approach to materials enriches each work: artifacts of and offerings to a people.

[1] UCLA Labor Center, “Nail Files: A Study of Nail Salon Workers and Industry in the United States,” https://www.labor.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/NAILFILES_FINAL.pdf

This feature was originally published in print for the Atlanta Art Fair 2024 broadsheet publication, taking place from October 3 to 6, 2024.