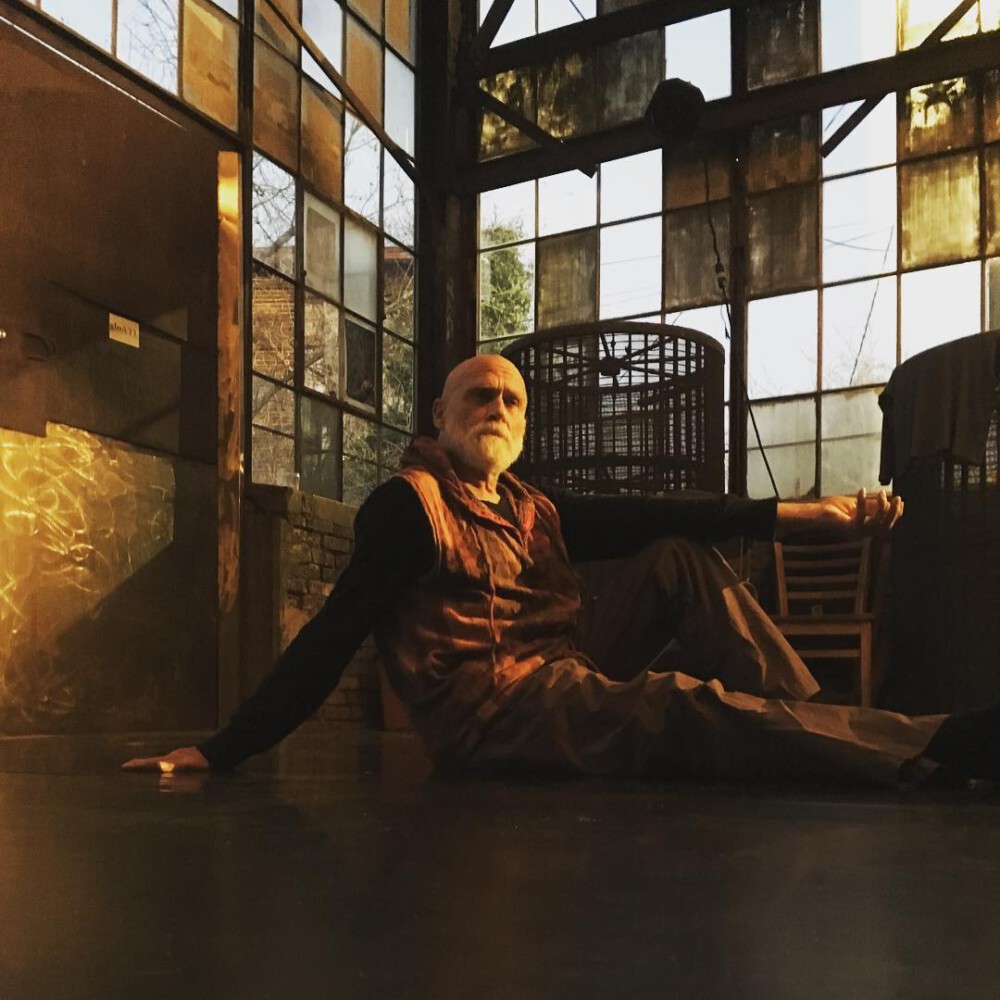

At a rehearsal in Atlanta in July, in the depths of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, onlookers gather to witness a rehearsal of the oft-reimagined Rite of Spring (1913) by the dance collective glo. lauri stallings, glo’s gentle leader, works delicately with the dancers, cajoling their movement with words and phrases like “curling,” “soft space,” and “deep time” situating the dancers’ bodies as material that is molded and shaped rather than a vehicle for imitation. At one point the dancers move in a roving promenade—hands interlocked, heads bowed—working to find a collective rhythm as they cross their feet over and under. The flatness of their line is reminiscent of the synchronized cygnets of Swan Lake, a ballet reference that is not far-fetched even though glo’s work does not often exist within the confines of a theatrical stage. stallings trained as a ballet dancer and danced professionally with stalwart companies such as Hubbard Street Dance Chicago and Ballet BC in Canada. She subsequently brings a balletic rigor and company model to her practice as her dancers perform consistently and regularly with pay, a rarity considering the often-precarious employment of an independent dancer. This circling promenade, referencing both a folk dance and the corps de ballet, will eventually be used to gather the onlookers of this new iteration of Rite of Spring, dissipating the line between dancer and audience, a signature aspect of glo’s work.

Rite of Spring is a fitting window through which to consider stallings’ archive as it is a work whose own archive continues to grow and change with each new iteration. Rite of Spring was originally choreographed in 1913 by Vaslav Nijinsky of the Ballet Russes with music composed by Igor Stravinsky. Since then, the ballet has been re-staged or reimagined numerous times. As much as stallings is adding to the archive of Rite of Spring, she is also reworking the archive through her retelling of the story, creating a new palimpsest. However, dance has always had a tricky relationship with archives and documentation, the form disappears as quickly as it appears, which lends itself to the romanticization or politicization of the form but also complicates preservation. How do you preserve something that disappears? This “problem” has produced interesting results in recent years, particularly as mid to late-century choreographers and companies consider how, or in what form, their legacies will live on. Merce Cunningham’s company performed a final world tour for two years after his death in 2009 before eventually dissolving leaving audience members clamoring for the last chance to see Cunningham’s living archive.1 Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions (1960-1961) were the first dance acquisitions for the Museum of Modern Art in 2015, which includes both the physical objects alongside written and video instructions and early documentation.2 The Martha Graham Dance Company and choreographer David Gordon have incorporated their own archives into performances creating performances comprised of embedded narratives.3 Currently, the dance world is abuzz with Edges of Ailey, a sprawling exhibition on the preeminent choreographer, Alvin Ailey, at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

In many of the iterations above, there is an emphasis on photography and video documentation. Indeed, when I asked stallings if I could write about her archival process for her 15-year-old company, I was expecting to see just that. However, one of the things she first shares with me is a small brown bag filled with bright cobalt sand. She brings the sand out while speaking with one of her dancers, Maurice, who smiles at knowingly. The sand came from a project that stallings and Maurice were a part at the High Museum of Art in 2017. For the exhibition, Daniel Arsham: Hourglass, stallings was commissioned to create the choreography for Arsham’s Japanese Zen Garden installation in which Maurice performed. The normally austere gallery was filled with this bright blue sand amid a pagoda structure of the same color. stallings described how the bodies of the movement artists, including her and Maurice, touched this sand and in turn the sand stained their bodies, leaving physical traces of their movement embedded on their skin, in crevices, even their teeth. The fact that she continues to carry this blue sand with her, holding fast to it these past eight years to share with Maurice at this moment, is significant. The sand holds the traces of their previous collaboration and appears as an offering for this new moment of artistic development.

How do you preserve something that disappears?

In addition to the attention paid to the physical spaces glo inhabits, central to stallings’ archive are the material exchanges that spring forth from her work. As mentioned, glo is known for their engagement across disparate sites, what stallings often refers to as the “margins.” Certainly, the company moves between centers and margins of art and culture. One week you may find them at a major museum while the next they are in pastoral Georgia. One of glo’s longest, durational works is The Traveling Show (2013-present), in which the company works in a rural locale in the deep South, often in partnership with other community organizations, over a long period of time. Last year they could be found in and near Boykin, AL, the home of the Gee’s Bend quilters. More recently, they have begun working in Coffee County, GA. In lieu of any sort of formal evaluation, the community members impacted by The Traveling Show often leave behind gifts for stallings and her dancers. stallings describes books that have been left behind, even personal notes stating the significance of glo’s engagements. stallings shares one of these notes with me. The writer states they don’t know each other, but nevertheless proclaims stallings’ artistry. She seems disappointed she cannot remember the actual person, still the sentiment is held dear and becomes part of stallings’ cumulative archive.

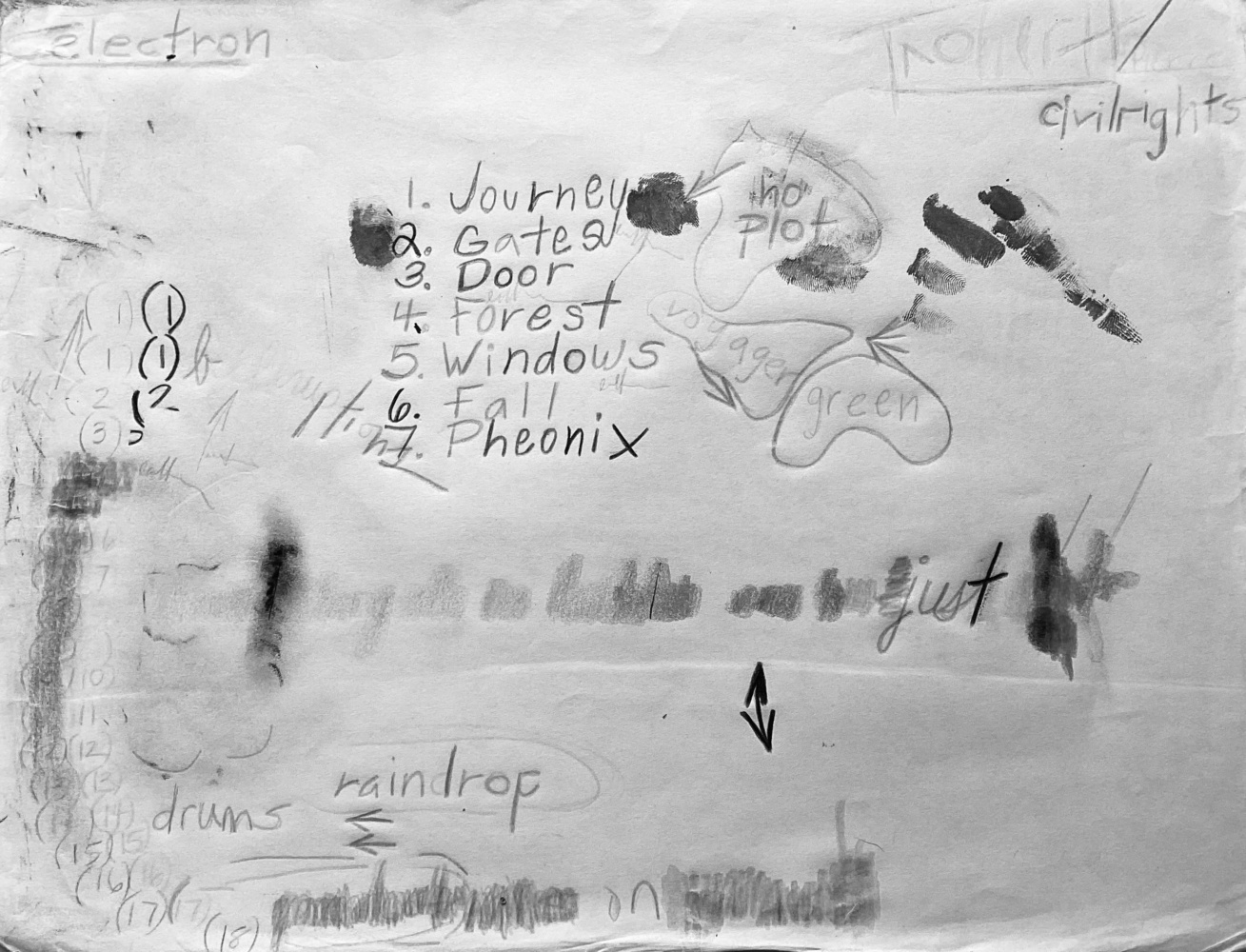

Another core part of stallings’ process and archive is her development of maps. The maps are used as documentation of her process, but also as a mode of translation and wayfinding for the various people her work touches, from curators to community members to her own dancers. The maps are comprised of words, colors, and images and although they share similar attributes, no two maps appear the same. Sitting with the copious versions, stallings can easily track her artistic development. For example, she notes turning points in her practice such as the influence of zoo biologist Heini Hediger and his work on proxemics, the study of human proximity that has shaped her understanding of relationality. The maps also recall other forms of dance notation and translations of movement to paper, from the Beauchamp-Feuillet system of notation in the eighteenth century to the maps and scores of choreographer Anna Halprin in the mid-late twentieth century. Both examples demonstrate the different methods and outcomes in visually representing movement and duration in a static image, thus producing abstract and striking imagery. Like stallings’ maps, dance notation not only serves as a functional object, but an aesthetic object as well. I ask stallings if any of the various institutions she’s worked with have accessioned her maps as part of their collections. The answer is no.

This absence may be because art institutions are still figuring out how to incorporate dance in their collections. I remember my surprise (and thrill) in 2012 to see the drawings of choreographer Trisha Brown’s work Locus (1975) hanging in the Museum of Modern Art. Like Brown, stallings’ work is part of a genealogy of dance artists whose work brings forth challenging, but productive tensions between dance and visual art as related not only to archives and collections, but how institutions situate visuality and canons of art history to incorporate dance.

After spending my time handling the delicate debris, maps, and ephemera of stallings’ archive, I return to my initial expectations around photography and video. Although stallings mostly shared the disparate objects within her archive, she is constantly filming rehearsals, holding her iPad as a loving parent might, capturing the dance and then subsequently sharing on social media. Yet, when asked about media documentation, she interestingly doesn’t speak to sanctioned documentation or collaboration with photographers, but rather the unsanctioned documentation that social practice and other publicly engaged forms of art are subject to. She recalls working in Central Park in New York as part of a Creative Time project where someone approached her and asked if she was making these works for people to take photos of them. Although most audiences would never use their phone during a performance in a theater, audiences in museums and other public spaces have different expectations and norms. Some dance artists are buoyed by audience documentation and how that documentation continues an afterlife across social media. However, there are others that resist any form of documentation. Artist Tino Sehgal, most famously, does not allow documentation of his performance works. stallings cites not only safety concerns for her dancers, primarily because she mainly works with women performers, but also the ease with which others can appropriate her work. Yet, she struggles with dictating how audiences participate in her work.

Can one experience “deep time” with a mediated exchange? A cell phone might be considered counter to what stallings’ work is asking of her audience—to find the magic in the ordinary, slow down, and shift our orientation to the physical world. Yet, I imagine many viewers are compelled to document because they want to carry the magic stallings and her dancers create with them.

[1] Simone Forti, Dance Constructions, 1960-61, performance, The Museum of Modern Art.

[2] For more about Forti’s acquisitions by MoMA, see: Metcalf, Megan. 2022. “Making the Museum Dance: Simone Forti’s Huddle (1961) and Its Acquisition by the Museum of Modern Art.” Dance Chronicle 45 (1): 30–56. doi:10.1080/01472526.2021.2024724. Catherine Wagley, “How MoMA Rewrote the Rules to Collect Choreographer Simone Forti’s Convention-Defying ‘Dance Constructions’”, artnet, September 18, 2018, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/moma-rewrote-rules-collect-choreographer-simone-fortis-convention-defying-dance-constructions-1350626.

[3] Michael Kliën, choreographer, Excavation Site: Martha Graham U.S.A., January 16, 2016, Martha Graham Studios, New York. David Gordon, choreographer, Live Archiveography, April 20-22, 2017, ODC Theater, San Francisco.