This essay is presented in partnership with Temporary Art Review, a platform for contemporary art criticism that focuses on alternative spaces and critical exchange among disparate art communities.

This essay is presented in partnership with Temporary Art Review, a platform for contemporary art criticism that focuses on alternative spaces and critical exchange among disparate art communities.

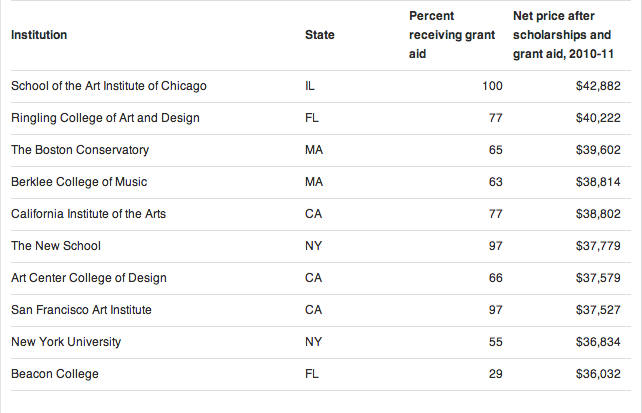

A few months ago on Facebook, I posted an idea I had about graduate school for visual artists. It is actually an idea I’ve had for some time, and one that seems increasingly relevant the more that is published on the arts being a career for the privileged, or art schools ranking as the most expensive four-year programs in the nation. Having attended one of those expensive schools and now making (part of my living) teaching at it, I am embarrassingly familiar with the cost-benefit analysis of an education and career in the arts. In 2001, when I attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I took a gamble on my future, taking nearly $70,000 in student loans to cover my two years of graduate school tuition (made a little bit more expensive by an extremely unfavorable exchange rate between the Canadian and American dollar at the time). I was 25 and had attended a visual arts college in my hometown of Calgary, Alberta, that had cost considerably less. When I got into SAIC, I decided that the benefit of a larger art community, access to the American visual art world, the potential of finding better teaching jobs with a degree from SAIC, and the seemingly endless list of resources the school offered were well worth the investment. I had been hammered with the “invest in your future”/”student loan debt is ‘good debt’” rhetoric, and as the first person in my family (siblings, parents or grandparents) to go to college, let alone graduate school, I was perhaps a little too caught up in the honor of being accepted to a “top school.” With no disrespect to the quality of education I did or one might receive at SAIC, I should have been a little less flattered, a little less starry-eyed – but at 25, hopeful that I would “make it” and filled with a kind of follow-your-dreams delusion, I felt that the arts shouldn’t be a career just for the rich, and that I would make this work for me … at all costs.

This isn’t a short article on regret – but some basic things I wish I had known: the percentage of tenure-track jobs versus adjunct positions in the job market and the average rate of pay and benefits for these positions; and the significant resources state schools had in terms of faculty and opportunities. The first is information only recently coming to light, and in my experience rarely if never talked about or shared openly with students. I had been told repeatedly as an undergraduate, “look around you, only 5% of your colleagues will be working in the arts in 10 years,” but the wages and cost-of-living for the average teaching artist were never disclosed. I had plenty of faculty tell me that I should look at teaching as a career some day, but not one said that the majority of teachers were adjunct or even anticipated that the corporatizing of colleges was quickly forcing those in these positions into the ranks of the working poor.

In terms of state schools – well, that’s my fault for not being a more diligent researcher and using some logic: take the number of people graduating with MFAs every year and consider the number of programs offering MFAs. There are more artists than teaching jobs, and thus there are some very fine, very talented, very notable people teaching at schools that never or barely rank in the US News top schools listing. Had I been a little less dazzled and a little more savvy I might have found my way to apply to any number of the great public universities in and around Chicago, who employ some of Chicago’s finest contemporary artists and thinkers.

Now, like most young hopeful artists, I was filled with the confidence and hubris pretty much required to embark on such a career in the first place, and felt pretty convinced that my decision was sound and I wouldn’t look back. Years later, while I have made the absolute most of my education, my move to the United States, and the community I entered in Chicago, I would be happier without the debt that has hung around my neck like an albatross the last 14 years. The list of things I could’ve done had it not been for the debt is long, so I do my best to not obsess over it – but my experience, and the knowledge that that debt is not easily alleviated by the teaching opportunities available at this point, leads me to think of some other solutions.

So, let’s say you want the education that the arts provide? The critical dialogue, the community and networks, access to people you admire. Let’s say you are a mature student who did the BFA thing already and has a practice – you’re a painter or a filmmaker and you own your own camera. Let’s say you aren’t looking to piece together 6-8 adjunct gigs. Let’s say you simply want to protest the rising cost of tuition for a degree that has very low job placement. What does one get out of an MFA after all? For many, it is like a two-year long residency program: an opportunity to focus on your studio practice within a community of peers and mentors. Class work is minimum, and you chose the seminars you want to take based on the books you want to read for your research or the films you want to watch. It’s the dialogue most artists crave, in conjunction with the opportunity to expand one’s social and professional network.

Low residency MFA programs have responded to the growing number of mature students looking to complete a course of study around work and family obligations and often at a more affordable price. Meanwhile, DIY residency programs are springing up all over the country, offering artists affordable settings for summer getaways among peers in the field. Something about these two models colliding seems promising for rethinking the MFA, especially considering the average rate of pay for today’s college adjunct.

In a couple of conversations with artist friends who are AB-MFA (all but-MFA); that is, have made art consistently since acquiring a BFA and have been active in art communities in some way professionally, the idea of assembling a group of AB-MFAs or MAs to self-design a mentorship program and critical study group has been batted around. While I leave the administration to someone else to imagine on a case-by-case basis, some basic, preliminary math might look like this:

Take 10 artists whom you would like to meet, make art with, and engage in critique regularly but cannot afford the cost of graduate school (let’s say $30,000-$94,000 total, should they not get a free ride somewhere).

But they’ve been working, they have some savings, and pitching in $5,000 a year seems a lot more affordable and a lot less of a long-term burden.

That comes to $50,000 annually or $100,000 for two years of revenue for this group to spend.

Now rent a house or a farm or a retreat center for four weeks – two weeks per summer – with a kitchen for group cooking. There are several small artist residencies out there that could probably even help facilitate this for you. Let’s be generous and put that at $20,000 total.

That leaves $40,000 for books, food, equipment, travel and mentors.

Invite four mentors out per summer. Artists whom you’d like to deliver a lecture and do critiques. Visiting lecturers make an average of $1,000 to talk and meet with eight grad students at universities over the course of one or two days, or between $2,500 and $5,000 to teach a 15-week class as an adjunct instructor. If you want them to lead a workshop, just look at the poor rate of pay for adjuncts these days and you probably could be considerably more generous. Pay for their travel and put them up where you are staying and be good hosts. Chances are that since you are thinking outside of the box, there are people you like who like that you are thinking outside of the box, and will definitely come to meet and spend time with you and your cohort. Let’s say you pay around $3,000 per lecturer for stipend, travel, and food for one week of their time. You are doing better than most schools with that offer. Total: $12,000.

Now you are left with $28,000 for food, equipment, books and your individual travel. Maybe you can make it last three weeks – why not. Perhaps you pool money for equipment for use over two years. Perhaps you use some of this to take a field trip together. Maybe you spread some out over the year so that you can meet again in winter like many of the low residency MFAs.

In any case, this is a rough outline.

Why would you do this? How will you get a job with a homemade MFA? Well, I’m not certain the job market is going to be able to support the mass-produced MFAs so many of us are carrying at this rate. There aren’t too many jobs that require one to begin with, apart from teaching, and it might be worth interrogating how a vocation like the visual arts has become so simultaneously unregulated (in the marketplace) yet corporatized (in the institution) when once-upon-a-time it was a life-choice that was meant to represent subversive potential and a radical break with conventionality. [See:https://alternateroots.org/node/713] For many, an MFA doesn’t translate into a “job,” so perhaps paying the same tuition that others pay for degrees that do is a little absurd. As someone much wiser than I once said:

“Art is a new series of scenarios/presentations that creates new spaces for thought and critical speculation. The creation of new time values and shifted times structures actually creates new critical zones where we might find spaces of differentiation from the knowledge community. For it is not that art is merely a mirror of a series of new subjective worlds. It is an ethical equation where assumptions about function and value in society can be acted upon.”*

It would seem a logical extension of art to interrogate the corporatization of its own dissemination, and to do so beyond art objects that merely critique the market (but are sold within them) through actions that take back the field of art from its increased remodeling into a commodity. Rather than purchase designer educations, why not fashion the spaces and values we want for art, for ourselves?

Sarah Hunter, founder of Summer Forum seems to be one person who had a similar inspiration when she started what appears to (now) be a biannual program in 2011. Called the Summer Forum for Inquiry and Exchange, Hunter started the program when she was considering entering a PhD program and decided that what she wanted out of that endeavor she would attempt to get by assembling like-minded people for focused, thematic residency sessions that would roam from year to year to new locations. Her 2012 session on Utopias was held in New Harmony, Indiana; 2014’s session will be on Networks of Belonging in Joshua Tree, California. Hunter’s program ended up being modeled after traditional residencies, with an open application to attend. Attendees are responsible for reading a selected group of texts, and visiting scholars round out the program. While I have not personally attended (although I’m familiar with the organizers and past attendees), their statement on the website provides some sense of their objectives and a similarity in mission to my proposal:

Summer Forum for Inquiry + Exchange seeks to develop and provide radical spaces in which to facilitate and cultivate contemporary thought. Each adopted residency site acts as the central framework, primary text, and collaborator with specificities that initiate a dialogue. The chosen theme and texts form a commons from which a legible language can arise to contain a diverse and engaged community realizing spontaneous collaborative scholarship and communal creative action.

No mention of being an alternative to graduate school, but the framework is there. Free schools, on the other hand, have been coming and going for some time, proposing something similar via skill-sharing and reading groups.

Of course this isn’t for everyone. Nothing is. But debt is looking considerably less manageable in the face of a rocky economy, and it is one solution I can proffer for those who want an opportunity to develop their practice and thinking in a focused, self-directed way without investing in the piece of paper. While DIY has gotten a bad rap by some for being “neoliberal” by aping the entrepreneurial habits of that economy, it might be time to consider what the potential and terms for DIY might be when applied to the goods and services that are becoming inflated disproportionate to the average wages of adult workers in a variety of fields.

*Liam Gillick: The Good of Work in “Are You Working Too Much? Post-Fordism, Precarity, and the Labor of Art” Sternberg Press, 2011.