At eleven years old, I was baptized on a Sunday afternoon, at my great uncle’s church in Forest Park, Georgia. I remember it being a special day. My sister and I wore white terrycloth dresses and flowing skirts that fell to our ankles. Shower caps hugged our plaited scalps. I felt beautiful, giddy, excited to be filled with the Holy Ghost. Saved, is what they called it at church, where I grew accustomed to seeing family run up and down the middle aisle of the sanctuary, shouting and speaking in tongues. I yearned to know what moved them.

In the moments before our baptisms, us children lined up on the stairs that led to the pool. Someone guided me into the water, and I was dipped back with arms crossed over my chest, eyes closed. I do not recall the congregation’s songs or the words that my uncle said to me. I remember bright light, then warm water filling my ears, and a towel enveloping my small frame. The entire experience felt much quicker than I expected. Before it was over, I wanted to do it again.

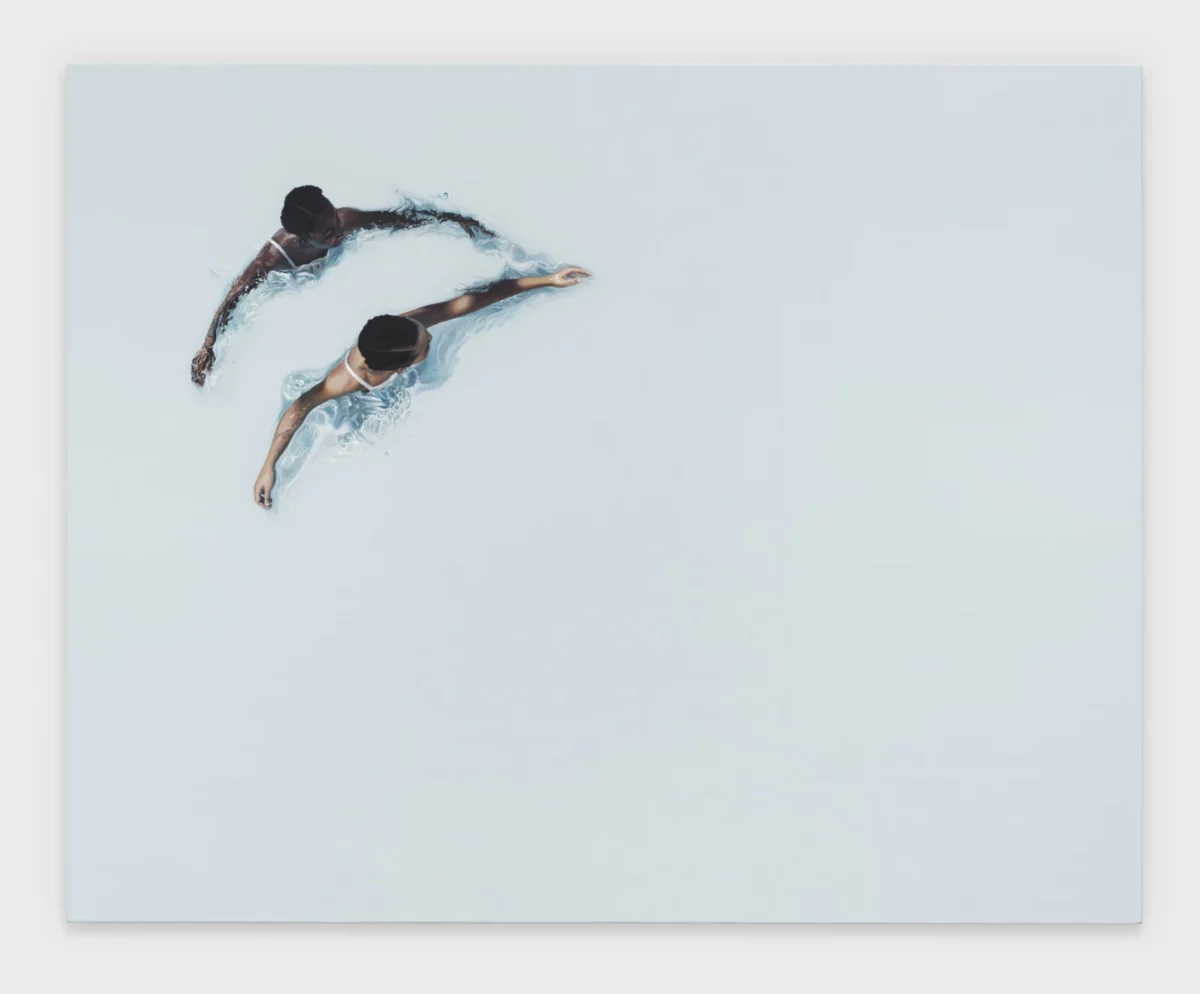

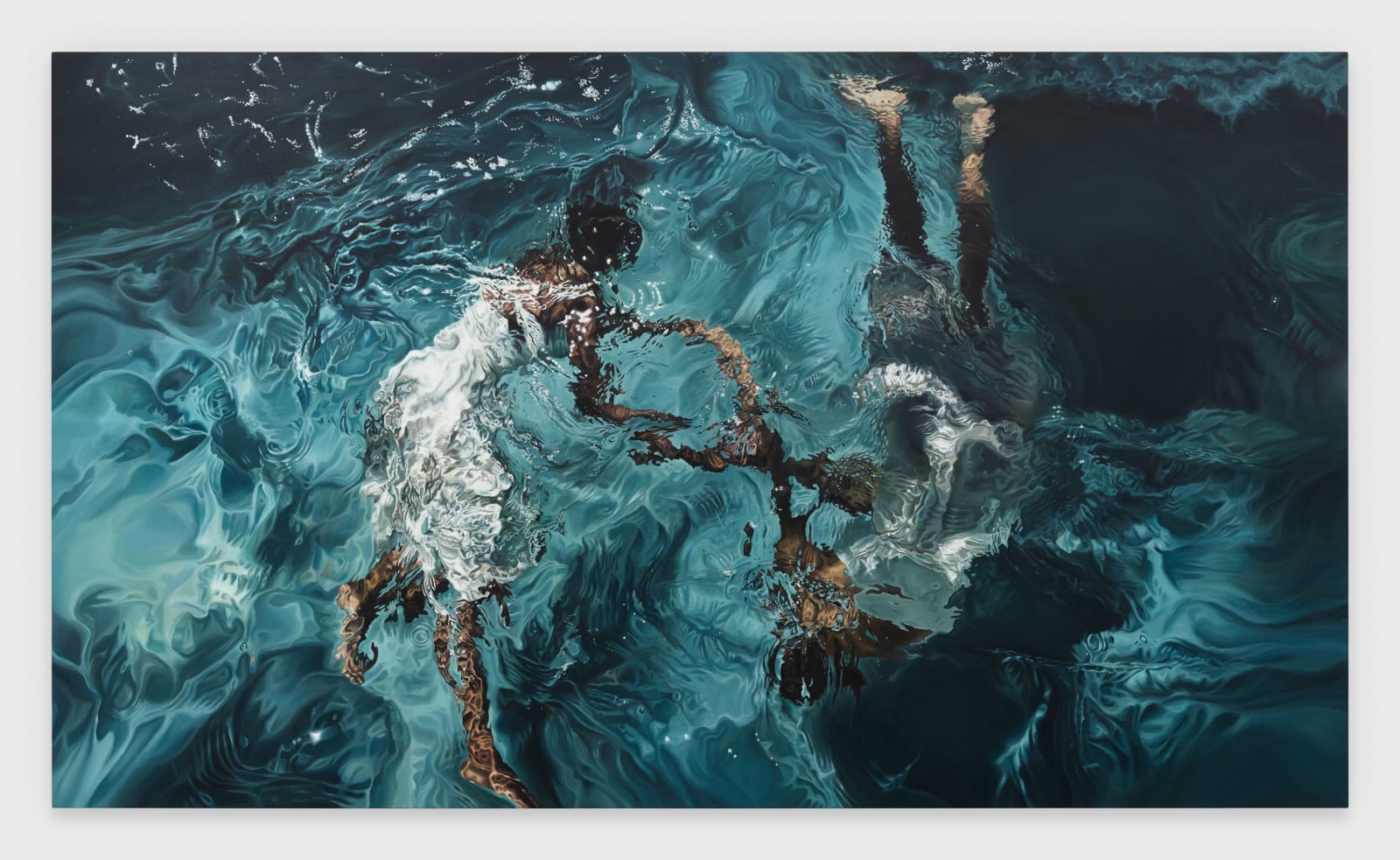

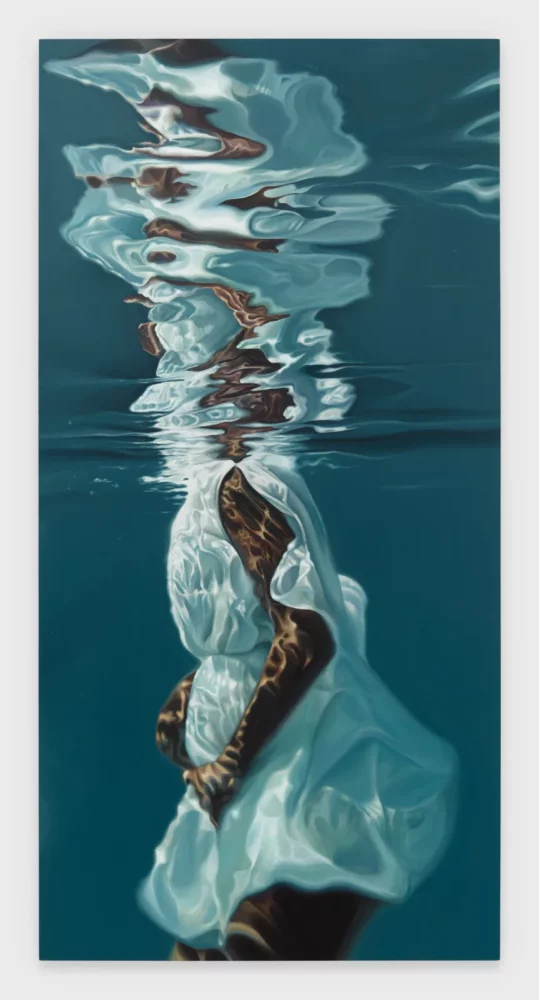

Thirteen years later, while viewing Thy Name We Praise, a new work by Los Angeles-based painter Calida Rawles, I am brought back to my uncle’s church on that Sunday afternoon, where I surrendered my life into God’s hands. Rawles’s virtuosic painting is a testament to the glory of a wave. She revels in a ripple’s revival. Water trembles, bending across multiple dimensions. Catching light, white fabric becomes a flame, billowing brightly as if met by breath or wind. Arms out-stretched, the figure gazes upward, her body like a tree planted by the rivers of water. Agape and awaiting. It is a loving embrace, a sweet surrender.

I met with Calida Rawles over video call to discuss her artistic practice, inspirations, and Black American Portraits, an exhibition featuring Thy Name We Praise, now on view at the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art through June 2023. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Bryn Evans: What’s going on in your world? What are you up to?

Calida Rawles: I’m starting the work for my Lehmann Maupin show opening in November. I’m painting very large pieces. And since I take a lot of time to make each work, it’s time to start. I have to get ready. I’m excited.

BE: Our conversation today is grounded by the Spelman Museum of Fine Art’s exhibition, Black American Portraits, which was first presented at LACMA in Los Angeles. You have a new commissioned piece in the show at Spelman, which also happens to be your alma mater. In my research, I discovered that at one point you were toying between different majors. You chose art, and now your work has been acquired by the very school that you studied at. How does that feel?

CR: It feels like an honor, especially looking at how I have developed over the years and how Spelman College has grown. I remember when the museum was being built, from its inception. I was there when they christened the doors of the building. I remember the first time walking in the space. I may have fantasized about having my work hang on those walls, of course, that was a fantasy of every art student. For it to come true is very exciting, and I’m happy to be in this position.

BE: I read that you have a great love and appreciation for literature, and this appreciation seems to seep into your paintings. The exhibition page for A Dream for My Lilith opens with an epigraph from Toni Morrison’s essay, “The Site of Memory,” which has been incredibly generative for me and my own work over the past several years. And these literary muses continue: you’ve shared that Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man was influential to your discovery of light’s interplay with water, that you hope to be like “a visual Octavia Butler.” Also, you’re close companions with many writers. Can you share more about the role that literature has in your creative practice? When I called, did I catch you in the middle of an audiobook? [laughter]

CR: At times I listen to music while I paint, but I mostly listen to audiobooks. I just finished Between the World and Me. I had read it physically, but I had never listened to it, and it was really exciting when I put it on and I heard Ta-Nehisi’s voice. I will probably play it again because it’s such a jewel, with this beautiful prose writing folded into contemporary cultural criticism. It’s like these waves going through, you know? It’s very poetic and just masterful writing.

A lot of times, I will relisten to certain books. I go back to Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents every once in a while. I love James Baldwin’s writing. I’ve enjoyed Madeline Miller and her writing with Circe and Song of Achilles. Of course, Roxane Gay is a major influence with Bad Feminist. Jesmyn Ward’s writing is just so lyrical and beautiful. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americana, you know…those are just classics that I can easily do.

When I did the paintings for A Dream for My Lilith, I listened to Naomi Alderman’s The Power over and over again, thinking about the idea of power, which is something we’re constantly struggling with even today. At the basic core, who wants to be in power? What happens when one is in power? It often corrupts. When someone has the power, it’s often abused.

BE: I have been thinking about the ways that power shows up in everyday relationships, specifically given my positionality in this world. At times, it’s frightening. But then remembering the power that I myself wield is very necessary and—I will not even lie—it’s oftentimes forgotten. But there’s a kind of tension present. Because sometimes it’s like, well, I don’t even want the power, you know?

CR: It’s in all different relationships. I am always interested in the human condition and the psychology of people. A lot of the literature that I like to listen to, or read, breaks down to those key elements about the natural instincts of humans. Maybe it allows me to forgive, because I recognize that it’s very easy to abuse when you have power. And I don’t want to be like that. I think about that often and also about ways that we could move beyond those positions.

BE: Your ability to see water is very profound, specifically your treatment of light with water. I love reading about your descriptions of water as a metaphor, and water memory and water work. And I was very inspired to learn that you didn’t grow up swimming, but it’s now a part of your daily life.

CR: I love water. I have not been swimming a lot since the pandemic. I just haven’t gotten back into my routine yet, but it’s very therapeutic for me. I need it and it’s time for me to go back because I’m getting on everybody’s nerves in my house. [laughter]

Because I didn’t grow up swimming, the first second I get in the pool is always a little frightening. But then I get into it and I’m fine. It is about being comfortable in something that is larger and bigger than you. It’s about trusting your body and relaxing in something you can’t control. And if you take that on and think about it, that sensation is embedded in all of my work. Of trusting this space and place that we don’t have control of and realizing there’s a higher power that you just have to believe in and keep going. That thought process is what keeps me going even today. When you look at the news and what’s happening with the world and government, you can become so scared. Any time that I start to think, oh, this is all too much, I think of my ancestors. In my studio, I keep a picture next to my desk of my mom’s great grandparents: Burton Payne and Martha Turner Payne. They were born in 1827 and 1833. I look at this picture every day. I can’t imagine being born in 1827, and they lived a long time, too, because Burton lived until 1922 and Martha lived until 1933. They’re smiling in this picture. When you think of Black people born in 1820-something or 1830, there’s an idea in my mind that they wouldn’t want to smile.

But they’re smiling and together. They had hope. They were married. They made a family. I’m their descendant, and I can’t even begin to imagine what they went through in their daily lives, but they had faith enough to keep going. I look at this lineage that I come from. What do I have to complain about? What do I have to be afraid of? Not much. I am a blessed human being to be born in this time where I can voice how I feel without major repercussions. I can paint during the day as an occupation. I have control of what I do on a daily basis. I am living in blessings. When I think about that, I know we can make it through. We got this. Which isn’t to say that people don’t want to set us back, but we’re starting from here. And that gives me hope.

BE: I was thinking of something similar earlier today. As I grow older and begin to access things that my parents, and certainly previous generations, do or did not have access to—it’s startling. I could leave America, I could not have to deal with gun violence. I could not have to deal with the police. To a certain extent. But my family’s from Georgia and Alabama. That’s the soil that knows me. That’s the water that knows me. It’s difficult to feel so much love for these geographies, while being aware of the terror that’s marred the land, which has morphed and changed and shifted with it. It’s beautiful that you keep those photos of your ancestors so close.

CR: You made me think of something I read of Baldwin, when he left the United States and went to Paris. It was freeing because he was able to think and move in a way that allowed him to escape from the segregation and the violence that was happening in the United States at the time. But he had to go back home. And that’s a very complicated experience that we have as Black Americans.

It’s kind of like when you go home and you tell your parents the things that they did that hurt you. Some of us get to a place where we’re so happy for everything that they’ve done, but at the same time, we can recognize where they could have done better and how we can move forward to becoming healthy adults with better relationships. In a way, that’s where I think we are as Black Americans, we’re telling our home, this is where it went and is going wrong. We’re asking for that recognition, so we can move on and forward. But we’re dealing with a country that doesn’t want to talk about the mistakes, and doesn’t want to recognize where we need change.

BE: Speaking of ancestry and descendants and relation, I smiled after reading that your daughter supports you as you take your photos for source material. It reminded me of my mom’s relationship with me and my sisters.

CR: Oh, that’s sweet. My daughters definitely help me with my photoshoots. They help me around the studio at times, and are inspirations for my work. My oldest girl is going to Spelman next year.

BE: That’s phenomenal. I’m so happy for her.

CR: I’m excited about that. She is one of my three girls and I have an older son.

BE: I was also reading your conversation with Jordan Casteel and Roxane Gay in Gay’s guest-edited section of the Winter 2022 Gagosian Quarterly. One thing that you said in that interview, that will probably impact the way I interact with artists forever, is: “I can talk about the pieces, but I don’t want to. I painted them. If I wanted to articulate so much, I would write a book.”

CR: [laughter] First of all, I sound like an asshole. Okay, keep going.

BE: [laughter] No, you don’t. As an emerging writer in this field, I can use this insight to learn more about the ways in which relationships between artists and writers can grow and expand from what they’ve been in the past. I am interested in knowing if there’s anything you would tell visitors, critics, or interviewers? There are many of us who seek out a definitive answer about an artist’s work. What would you tell them? There’s so much that we don’t see when we look at a work of art.

CR: Bringing all of your history and your experiences to the work is the most important thing. I learn a lot about my work from listening to other people. Sometimes people will say something, and I’m like, yeah, I did think about that while I was painting, but I may have forgotten. Everyone goes to a work of art and brings themselves to it. Their interpretation is just as important as the artist’s interpretation, I think. I wanted to give room for others to bring themselves to the work and share their story.

BE: Right. As a poet, I don’t want to say everything, because some things are for myself. And, like you’re saying, I want to know what you think versus explicitly telling you what to think.

CR: Exactly, and that’s what I’m often trying to do. I do this thing where I write my thoughts surrounding my work, for example on Instagram, but sometimes I feel like I shouldn’t, because if I left it out, people may say what they were thinking more. But people are always asking me, so it’s a Catch-22. They want to know what I was thinking when I created it, then it leads their brain to those spaces. But that’s just what I was thinking, it’s just my thought. That doesn’t mean yours is any less valid. When I created it, I feel myself channeling energy, and I put it all in a material being or form. But you could see something else from the work, and it’s just as valuable and just as important.

BE: Over the past few years, I have noticed the intentional usage of water imagery in Black popular culture, particularly in notable films directed by Barry Jenkins and Ryan Coogler. There is the gorgeously shot, heartfelt scene in Moonlight, where Juan teaches Chiron how to swim, and the moment becomes a sort of baptism.

CR: I loved it. It was one of my favorite parts.

BE: It reminded me immediately of your work.

CR: I noticed those images for sure. I love the moment in Moonlight because it made me think of intimacy and trust. The scene depicted the building of trust between this man and this child. As we discussed earlier, my work is about trusting in something larger than yourself. My subjects always look comfortable in this large body of water. I also love Daughters of the Dust. It’s one of the most beautiful films I’ve ever seen in my life. I think [Jenkins and Coogler] did an amazing job. I have noticed it, too—a lot of people are doing water. I’m just gonna keep going.

Black American Portraits is on view at the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in Atlanta through June 30, 2023.