Awilda Sterling-Duprey started thinking about movement during her childhood drives between Arecibo and San Juan, Puerto Rico, her mother’s and father’s hometowns, respectively.1 She watched the palm trees and ocean waves zoom past her car window like frames on a reel. The seventy-seven-year-old artist came of age in a Puerto Rico that was making strides towards an independence it still hasn’t reached (still striving, still reeling). As the sixties welcomed liberation movements and change washed over colonies all over the world, Puerto Rico had barely managed to decriminalize its own flag and national anthem. In this shadow, a young Sterling-Duprey became a student at the School of Plastic Arts and Design, pursuing a bachelor’s degree, her second, in painting. She attended classes in a building that had already lived many lives: first as a military hospital, then a Bacardi Rum factory, and finally an art school.

In the 1960s, painter-printmakers were the protagonists of the San Juan art world, with their sharp, graphic lineations, which told clear, representational stories of nationhood and rural realism. But Sterling-Duprey grew restless and uneasy with this kind of painting, instead eyeing the gesture-driven work of the abstract expressionists and the action-oriented ethos of New York City’s budding performance art scenes. After spending some time in New York during the 1970s she returned to Puerto Rico more of a dancer than a painter. In the following decades, Sterling-Duprey became more and more committed to her work as an experimental dancer and choreographer, co-founding Puerto Rico’s first experimental dance collective, Pisotón. She also toured the Caribbean, spending a considerable amount of time in Cuba. During her travels she continued to observe the familiar sway of the palm trees and that same curl of the waves.

Throughout her decades-long career, Sterling-Duprey has paid close attention to how movement appears in painting and how dance lends itself to its own kind of painterly gesture. She has distilled elements of both disciplines to their constituent parts, which can be broken down into kinds of information: visual, spatial, tactile, sonic, and so on. Her work demonstrates how information—in the form of sounds, light, spaces, and colors—can bypass words, but not the body, to become lines and squiggles on a piece of paper or a painting on a wall. Hers is a practice of incorporating through repetition, of folding into her body and work every new lesson, skill, technique, or idea by going over it again and again. The more she repeats a gesture or listens to a sound, the more integrated it becomes into her being. “I like to learn and feel those new movements in me and how they make me feel part of a concept,” she explains.2

The integration of body and motion can be seen in the 2009 performance of Reggaeton Lento, whose title translates to “slow-motion reggaeton.” Sterling-Duprey steps onto the stage to Puerto Rican musician Tego Calderón’s “LoA shy za.”3 Observing on video documentation, one can see stage lights shining on the artist from above and from both sides of the stage. A rectangular sheet of white hangs from the wall behind her and every slow-motion hip swerve, booty pop, and deep squat is projected onto this makeshift canvas as an exaggerated outline, and her every move is echoed by a fleeting shadow partner.

Dance-Drawings

In 2020 Sterling-Duprey found herself back in her hometown, feeling out the labyrinthine walls of El Cuadrado Gris, a narrow house turned experimental art space. The artist was raised in Barrio Obrero, a section of San Juan now home to one of Puerto Rico’s largest Dominican populations. According to the artist, her grandfather managed construction of the area in the 1920s at the request of the city.4 Sterling-Duprety is confident that her grandfather’s company helped build what is now El Cuadrado Gris. In this space filled with personal history, she started working on her “dance-drawings.”5

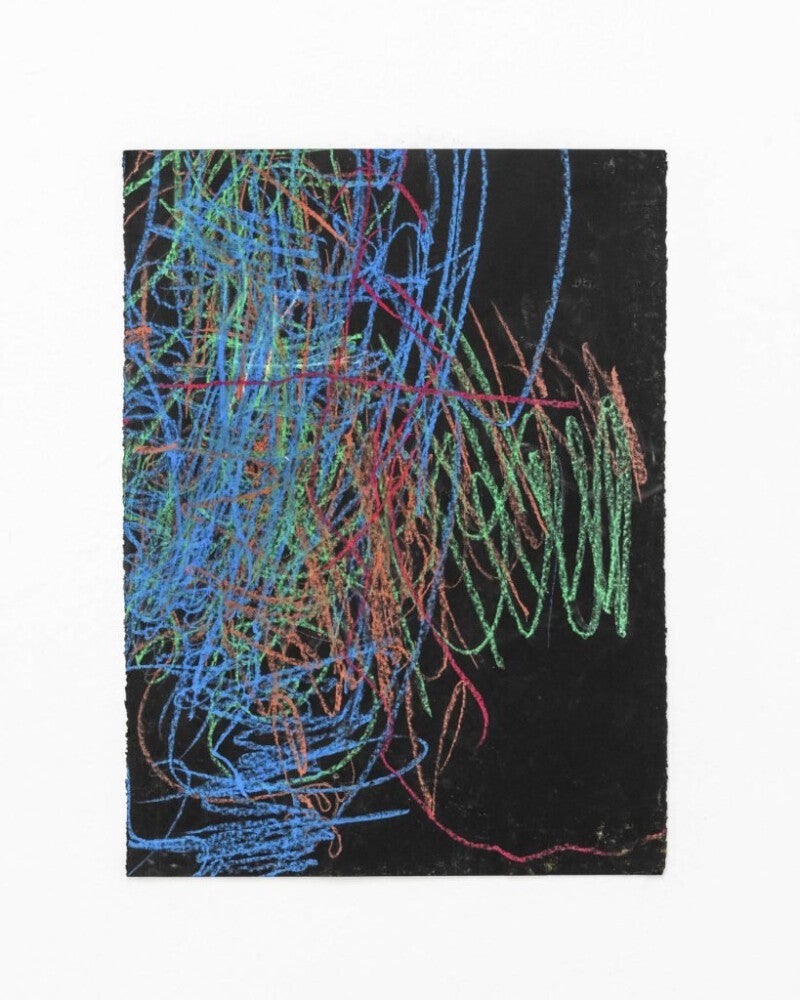

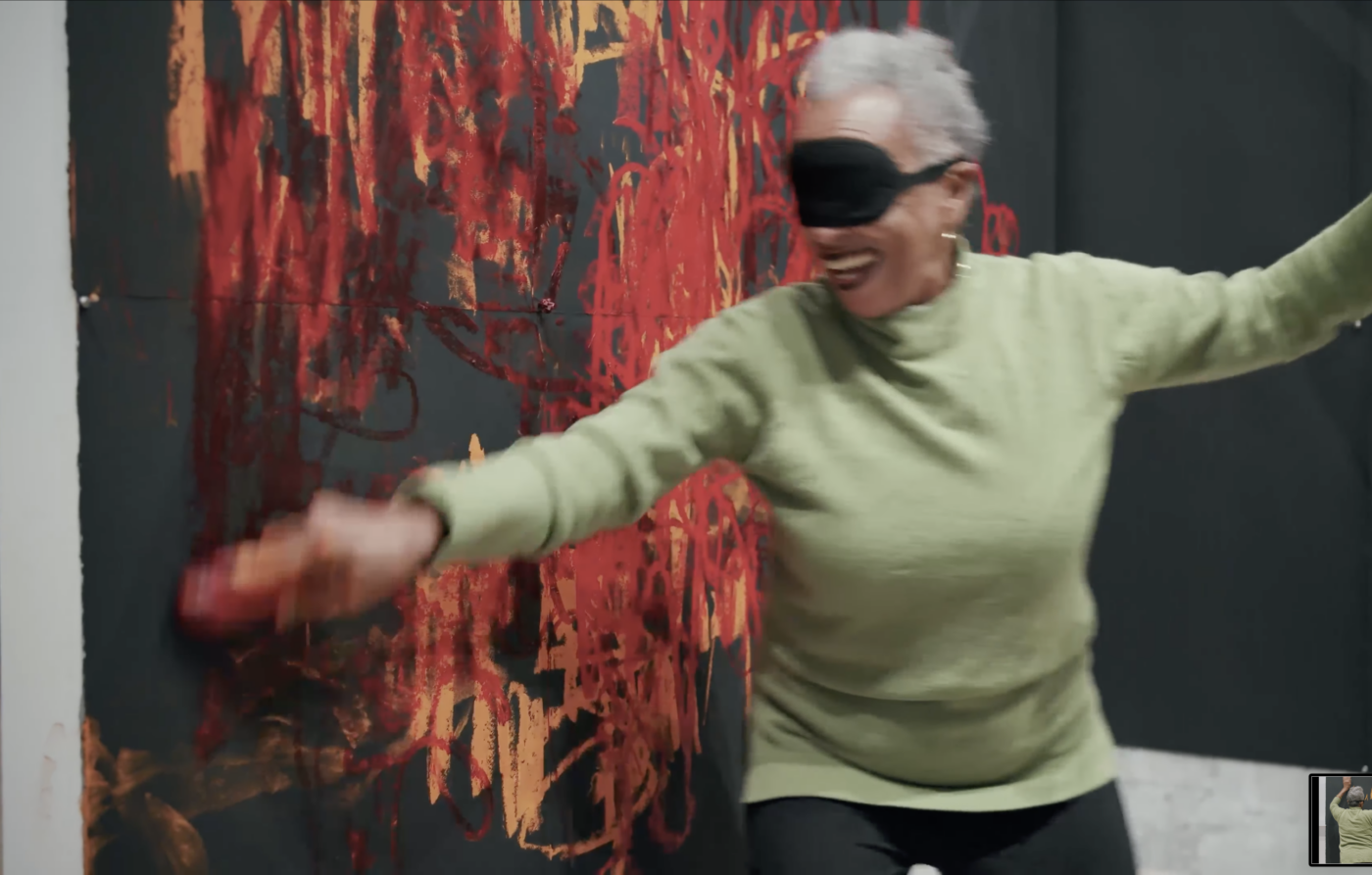

The dance-drawings often start with black backgrounds, including small sketchbook pages or large swaths of butcher’s paper painted black, which are then mounted on walls or easels. Nearby, there is a preselected set of oil pastels. Then, a blindfold is pulled over Sterling-Duprey’s eyes, the music plays, and she puts crayon to canvas. She draws to the music. When blindfolded, the artist says her entire body, especially the neurons in her brain, is sensitized and hungry for as much tactile and auditory information as she can take in.6

The mark-making is improvisational. As the link between her canvas and the music, the artist vibrates like a live wire. She drags her oil pastel, occasionally switching between crayons, unaware of the colors she is using. She draws at the behest of what she hears, feels, senses in that moment. References to other artists or allusions to choreography might leak through, but the only kind of premeditated moves to which the artist is willing to admit are the moments where her oil pastel flies off the edge of one piece of paper to find its way onto the next one. The resulting works show a range of drawing gestures: Some are bundled with scratches and coils; others are concentrations of lines and colors that appear to twitch in place before veering off the paper. Dance-drawings ultimately evolved into . . . blindfolded (2022–) which she performed at the Whitney Biennial in 2022. Archival footage of the performance shows the artist hopping while holding the pastel against her drawing surface, sometimes giggling, and occasionally raising her arm over her head to draw a big arch.7 When she’s done drawing, she wipes her hands clean and, still blindfolded, nails the color-soiled paper onto another drawing surface.

More recent works—like those found in Dark Drawings, exhibited at El Kilómetro in Santurce earlier this year—include smaller works that are more stenographic than choreographic, suggesting that Sterling-Duprey worked with a sketchbook or canvas on her lap. There is more negative space, yet everything feels denser. Clusters of colored lines look like they’re bursting from the corners or approaching the viewer from far away.

From . . . blindfolded to Dark Drawings, the viewer sees nothing but colored scratches over dark backgrounds: places of rest and stenographic exaltation where the artist often stops to go back and forth over the same spot. Giving those canvases more sound, more information, more contact, more heat, and more energy from the friction. Sterling-Duprey’s hand twitches and swooshes until the colors grow richer and thicker with texture and there is less oil pastel to hold onto. She says she pictures herself painting when she dances. And when she paints, she does it with her whole body. These two parts of the artist’s dance-drawing practice are joined together in an endlessly looping study of repetition and movement.

Repetition Is Key

Reflecting upon the inspiration for her dance-drawing, Sterling-Duprey thinks back to when she was an art student. In a 2022 interview with artist Miguel Trelles, she discusses her decades-long obsession with Franz Kline’s black paintings. “I had asked a teacher if I could copy Kline, to go like that,” the artist recalled.8 She made a swipe with her hand holding an imaginary brush—a gesture that stood in for the words she didn’t yet have as a seventeen-year-old. The teacher told her to copy what she saw, to recreate Kline’s gesture by imitating its trace. To repeat it again and again, faster and stronger each time. “I have realized that in repetition there is a moment when the pattern changes,” Sterling-Duprey told the magazine C& América Latina, adding that she finds this to be especially true when it comes to jazz.9

In Dark Drawings, her scratches are like drum fills or screeching saxophones. Her traces are frantic and sometimes diffused in their panic. The artist connects her use of jazz in her studio work and performances to the way Kline used to paint within earshot of the saxophonist Sonny Rollins. While she’s partial to the works of Miguel Zenón and Ismael Rivera, she is most-inspired by the essence of the “straight-ahead jazz style,”10 where repetition leads to shifts in patterns that in turn become a beautiful blur of music.

The lessons of repetition followed her into her career as a professor. In 2007, when she returned to teach introductory courses at her alma mater the School of Plastic Arts and Design in San Juan, she found herself revisiting the principles of tonal and chromatic scales, repeating them to herself and her students as she taught the same lesson semester after semester. She realized that every imaginable shade of gray, however indistinguishable from the next, is needed to depict three-dimensionality. She realized that repetition produced nuance. And through repetition, she incorporated that awareness back into her practice. “I make my own tonal and chromatic scale from the sounds I hear,” she said.11

Her traces are frantic and sometimes diffused in their panic. The artist connects her use of jazz in her studio work and performances to the way Kline used to paint within earshot of the saxophonist Sonny Rollins.

In Dark Drawings, Sterling-Duprey emphasizes these pauses and shifts through her use of negative space. One of the works has a black square at its center, where there seems to have been a piece of paper that was protecting the negative space underneath and which was lifted away after the drawing was completed. In another trio, the blackness pushes the lines into a single corner. Between these gaps and pauses her bright scribbles look like small explosions, contained booms and pows that threaten to dissipate as soon as they pop.

The artist’s frenetic lineations and repeat gestures become tangled clouds of color as she works her way along the page. With every repeated move, a new layer forms and the negative space grows smaller and smaller. Some of the Dark Drawings look like full-page washes of color, but closer inspection reveals more gaps and more pauses—small geometries of black or the uneven textures caused by the bumps of the corrugated cardboard underneath. Continuity is an optical illusion, the same one that binds together frames on a film reel to feign the appearance of a moving image. Like a rolling snare or hissing cymbal, movement is continuous in the blur of repetition.

Vulnerability of Motion

Sterling-Duprey does not have a grand unifying theory of what her art means. Throughout her decades-long career, the artist has always worked to assimilate media and information in order to rhythmically spit them out. Sterling-Duprey also offers no solution for continuity. Information moves from her body to the canvas, with dance being the only link. She uses gestures, movement, color, and space, and apart from what viewers might see in her performances, she does little to bind it all together. She floats from gap to gap, binding disciplines and media as she goes. In every sense of the word, her art is purposefully repetitive.

In these repetitions, and through the many gaps they produce, there is the kind of truth that replicates itself everywhere. In train cars and through car windows, in the frames on a film reel, in the buttons on a keyboard, in the zeros and ones of a computer. In the saccades of the eyes as they read along a line of text, shifting left to right to left like paper shuffling out of a printer. In the beat between an eight count and in the faults along the Earth’s tectonic plates, in breaths and heartbeats, in neuron synapses and gene sequences. The artist finds her way in spite of the demands for continuity, consistency, and solidity, in order to find an unending series of gaps, bound together by something as fleeting and immaterial as movement. Sterling-Duprey ignores the comforts of tidy conclusions and instead invites the viewer to join her in the vulnerability of being in constant motion.

[1] Boyer College, “Reflection:Response with Awilda Sterling Duprey 9/25/20,” YouTube video, 1:10:42, September 29, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_FiJ8tuTvIU&t=3527s.

[2] Boyer College, “Reflection:Response with Awilda Sterling Duprey 9/25/20.”

[3] Reggaeton Lento (2009), by Awilda Sterling-Duprey, was performed in Sala Beckett PACA in Río Piedras, Puerto Rico, July 2009. See mickeynegron 18, “Awilda Sterling Reggaeton Lento,” YouTube video, 3:33, September 5, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vc0OygyOx-M.

[4] Teatro LATEA, “Tertulia presents Awilda Sterling-Duprey w/ Miguel Trelles,” YouTube video, 56:03, August 25, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rxfEzk_m4cY.

[5] See “Awilda Sterling-Duprey: . . . blindfolded Performance,” Whitney Museum of American Art, accessed September 16, 2024, https://whitney.org/exhibitions/2022-biennial/performances/sterling-duprey.

[6] Teatro LATEA, “Tertulia presents Awilda Sterling-Duprey w/ Miguel Trelles.”

[7] Awilda Sterling-Duprey’s . . . blindfolded (2020–) was performed during Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April 6–September 5, 2022. See Whitney Museum of American Art, “Awilda Sterling-Duprey: . . . blindfolded | Whitney Biennial 2022,” YouTube video, 0:59, March 31, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xtPILp51iJw.

[8] Teatro LATEA, “Tertulia presents Awilda Sterling-Duprey w/ Miguel Trelles.” Emphasis my own.

[9] Awilda Sterling-Duprety, “Awilda Sterling-Duprey: (Un)Drawing the Continent Blindfolded,” interview by José Alvarez, C& América Latina, July 27, 2022, https://amlatina.contemporaryand.com/editorial/awilda-sterling-duprey-undrawing-the-continent-blindfolded.

[10] Teatro LATEA, “Tertulia presents Awilda Sterling-Duprey w/ Miguel Trelles.”

[11] Awilda Sterling-Duprety, “Awilda Sterling-Duprey: (Un)Drawing the Continent Blindfolded.”

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Crush.