As part of our year-long exploration of the theme Belief and Fiction and in conjunction with the much-anticipated opening of Betye Saar: Serious Moonlight, a survey exhibition of the artist’s “rarely exhibited immersive, site-specific installations from 1980 to 1998” at the ICA Miami, Burnaway is publishing an exclusive first-look from the forthcoming catalogue. The excerpted essay, Ritual and Reimagining: The Installations of Betye Saar is written by ICA Miami and Serious Moonlight curator Stephanie Seidel.

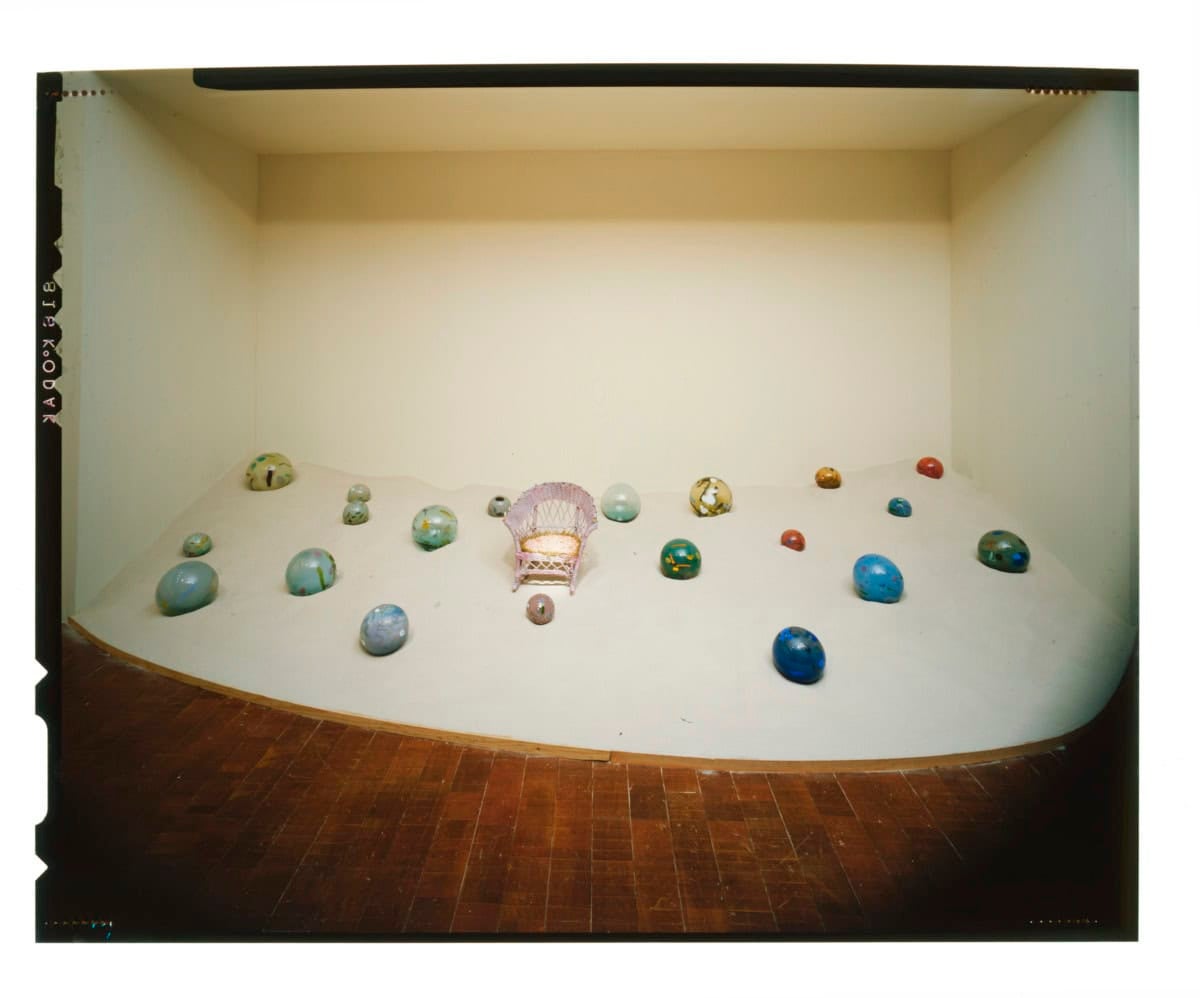

In the 1970s, the idea of art making as ritual took on central prominence in Betye Saar’s practice. She started incorporating the form of the altar in her work in 1973, which subsequently expanded into room-size installations. While Saar’s assemblages and altar pieces had already incorporated found objects sourced from flea markets and swap meets, those were much smaller in scale and maintained an intimate format. Saar points out that her installations in particular “evolve as ritual” in a process that is as much about her expression and exploration as it is about summoning the audience: “A formula develops, the procedure of gathering the materials/objects, the offering of the materials (art making), the placing (installation) of the materials, and the presentation of the viewer. . . . I am interested in the interplay of concealing and revealing, the layers of reality, and involving the viewer beyond the physical domain.”[1]

Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

For Saar, ritual is an activity that creates and releases energy, with the work as the amalgamation of this energy. Through the repetition of forms and the utilization of symbols, the artist aims to create a connection to something outside or beyond what is tangible or rationally quantifiable, and, more specifically, she does so with the audience in mind.

The immersive nature of Saar’s installations physically positions the viewer not only amid individual stories of transcendence and spirituality, but also connects them to longer-running sacred traditions, specifically ritual practices of the African diaspora. In each installation, the organization of the objects and materials follows the principles of “power” and “display” that Saar first encountered in regard to African sculptures as interpreted in Arnold Rubin’s article “Accumulation: Power and Display in African Sculpture” published in Artforum in 1975. Saar has often noted the great influence of this essay on her thinking, going so far as to apply Rubin’s categories to her works: “The installation, for me, is an extension of my assemblage/boxes. The assemblages serve as art objects but I became interested in expanding the scale and the concept of ‘power and display.’ I interpreted ‘power’ as intuition, as mystery, as ancestral memory, as personal experiences, dreams, feelings, and energy. The ‘display’ became decoration, pattern, color, design, the attraction and the seduction. I began to create an area around the sculpture/assemblage to include the viewer.”[2]

In interpreting display as “decoration,” Saar includes elements of applied arts that point to her early experiences as a costume designer for the Los Angeles Inner City Cultural Center theater, as well as her professional training in interior design in college. From the 1970s on, that background merged with her approach to sculptures and assemblages, resulting in the room-size installations that oscillate between sculpture and sets to be activated by viewers.

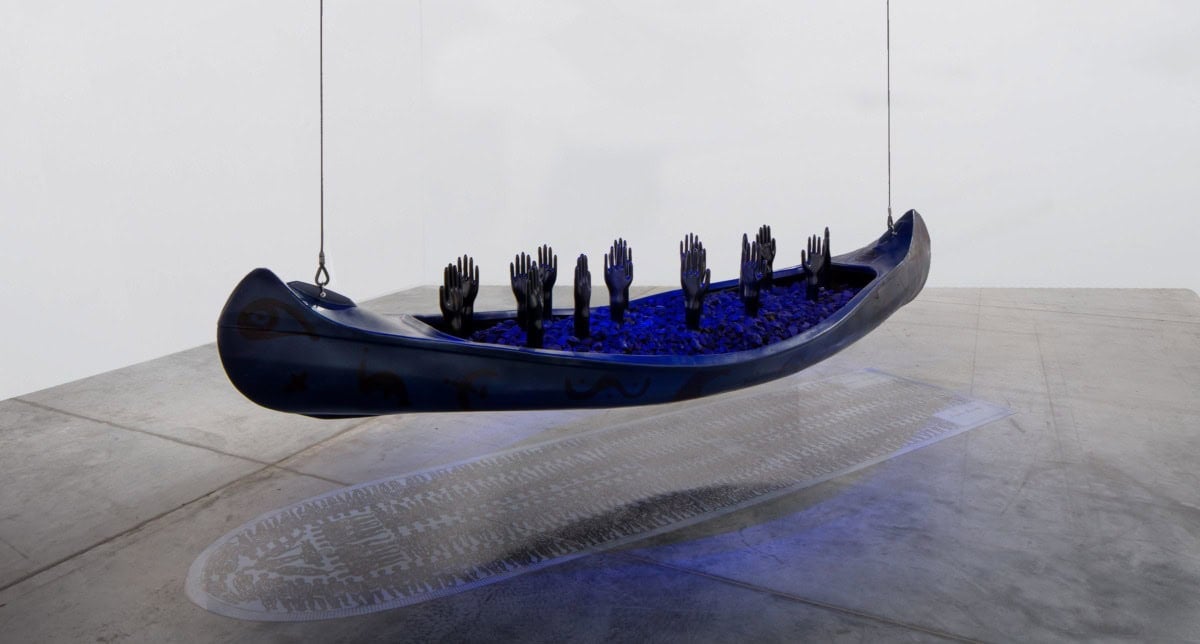

Take, for instance, House of Fortune (1988), an installation in which Saar transformed an Art Deco table and four chairs she purchased at the Rose Bowl Flea Market in Pasadena by adorning them with ancient runes and her own handprints. Reminiscent of the nineteenth-century practice of séance, this ensemble was presented set into shrubs found on the streets after a storm in Manila, where the piece was first exhibited.[3] These “power” elements conjured a complex mix of lived experience, spiritual meeting, and environmental energy, and were accompanied by “display” elements, including glittering paper pulp collages, four silk banners dedicated to the four elements, and a group of sequin pieces based on the form of Vodou flags (drapo Vodou). The glittering surfaces of such flags, which are made of densely stacked beads and sequins, especially embody Saar’s ideas about “attraction” and “seduction.” They are display elements but embody attributes of power at the same time as they point to ancestral memory through their connection to Vodou culture and its African origins, as well as to the diasporic present. The works’ motifs incorporate cosmological symbols, celestial bodies, and a number of icons that reoccur in Saar’s works throughout the decades: hearts, fans, snakes, a fish jumping through a fan, rolling dice, and a hand with palmistry lines.[4] The flags themselves are connected to the African diaspora via the transatlantic slave trade. “Veve flags,” as the artist refers to them, stand in the tradition of Vodou flags used to adorn Vodou temples in Haiti. Saar commissioned them in 1986 in Port-au-Prince, where they were made by local sequin artists.[5] Art historian Robert Farris Thompson points to the “profoundly liminal” character of Vodou flags as they “stand at the boundary between two worlds,” the earthly and the divine.[6] In this light, the flags point to what lies outside of the realm of the visual and remains intangible and what is deeply entangled with the African diaspora. In Saar’s installations, this liminal space is the source of ancestral memory and a past that is reimagined and reformulated in order to be experienced by her audiences. This is further elucidated in installations like The Trickster (1994), Diaspora (1992), and A Remembrance of Ritual (1997). Further, Brides of Bondage (1998) explicitly references the Middle Passage and the continued effects of slavery through the display of a white bridal dress and twelve miniature sail boats placed on its train, each one of them atop a diagram of the Brookes slave ship showing how enslaved people were stowed as cargo.

Saar imagines diaspora through the ritual process of creating and assembling the installations. Her practice of recycling materials transforms and expands the art objects into ritual artifacts—a process akin to summoning and gathering with herself as the conjurer.[7] In their unique sense of mysticism and spiritualism, the installations are deeply syncretic as they source from a collective memory that is simultaneously reinvented and reformulated.[8] With its séance arrangement and Saar’s Veve flags, House of Fortune connects ideas, mythologies, and symbolisms borrowed from different spiritual traditions. As Saar explains: “It’s not that I’m emulating Haitian voodoo or New Orleans hoodoo or Chango or Santeria or any of the different cults. I just take a little bit from each one. . . . Basically it’s one planet and how everybody contributes to that through their ethnic origins or their cultural practices.”[9]

Saar deems these different influences and quotations not as mutually exclusive but rather as an open field of possibilities that promise to transgress perceived cultural and spiritual incompatibilities. Similarly, an array of different objects included in a given installation forms a vocabulary of sorts that the artist then uses freely and continually reconfigures and recycles into new installations. None of the installations are fixed, completed ensembles but rather temporary configurations in continued evolution, just like the diasporic narratives they form. In Saar’s hands, then, ritual is not only the means of creating installations—and artworks more generally—but also the activity of remembering and connecting to the unknown, and, ultimately, the site for forging ties among newly reimagined communities. The last step of Saar’s ritual approach is establishing the installations as a place of communion. Through sharing the work with others, Saar evokes a sense of connectivity that shapes and shares meditations on the experience of diaspora. Through creating her own rituals to spark connectivity and community, the artist imagines different ways of understanding and knowing. Inviting her audiences to encounter the traces of a past that has forever changed the present, Saar creates each installation as a space of visceral experience.

Excerpt from the essay, Ritual and Reimagining: The Installations of Betye Saar, from the book, Betye Saar: Serious Moonlight, published by ICA Miami and DelMonico Books•D.A.P., New York.

Betye Saar: Serious Moonlight is on view at ICA Miami thru April 17, 2022.

- [1] Betye Saar, Betye Saar: Selected Assemblages and Oasis, ed. Julia Brown and Kerry Brougher, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1984), 45.

- [2] Saar, Betye Saar: Selected Assemblages and Oasis, 45.

- [3] House of Fortune was first exhibited at the Thomas Jefferson Cultural Center of the U.S. Embassy in Manila, Philippines, November–December 1988. The site-specific piece was commissioned by the United States Information Agency (USIA) as part of a five-venue exhibition tour of Saar’s work titled “Connections: Site Installations,” which toured Southeast Asia in 1988. In later iterations of the installation, the table and chairs are surrounded by ceramic hands holding tarot cards.

- [4] The motifs of Saar’s paper pulp pieces feature an iconography similar to the sequin flags with slightly different configurations: Heart, Dice & Fan (1987–88) and Hot Dice, The Serpent & the Cross, and Black Hand with Cactus (all 1987).

- [5] Saar collaborated closely with the sequin artists, even specifying the way the sequins should be applied: a flat sequin on the bottom with a “star sequin” and a bead on top for “scattered energy,” as she writes in her notebook. See Betye Saar, Notebook, 1985, entry August 6, 1985, p. 76. Saar’s friend Virgil Young, a visionary collector and major authenticator of Haitian art in the 1980s and 1990s, established Saar’s connection to the sequin artists for the physical fabrication and import to the United States.

- [6] Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983), 184.

- [7] Art historian Jane H. Carpenter compares Saar to a “conjure woman.” See Jane H. Carpenter, “Conjure Woman: Betye Saar and Rituals of Transformation, 1960–1990,” Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 2002. Art historian Richard J. Powell points to how Saar has “infused contemporary art with . . . a complex and summative response to existential questions and social hardships via the art of assemblage and the circuitous route of the conjurer.” See Richard J. Powell, “Betye Saar’s Mojo Hands,” in Betye Saar: Uneasy Dancer, ed. Mario Mainetti (Milan: Fondazione Prada, 2016), 241.

- [8] Houston Conwill states, in McCullough’s film: “I’m working from what Betye Saar calls collective memory.”

- [9] Karen Anne Mason, African-American Artists of Los Angeles Oral History Transcript, 1990–1991: Betye Saar. University of California, Los Angeles, Oral History Program, 1996, https://oralhistory.library.ucla.edu/catalog/21198-zz0008zpzb?counter=8, 93 f.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series Belief and Fiction.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2021 here.