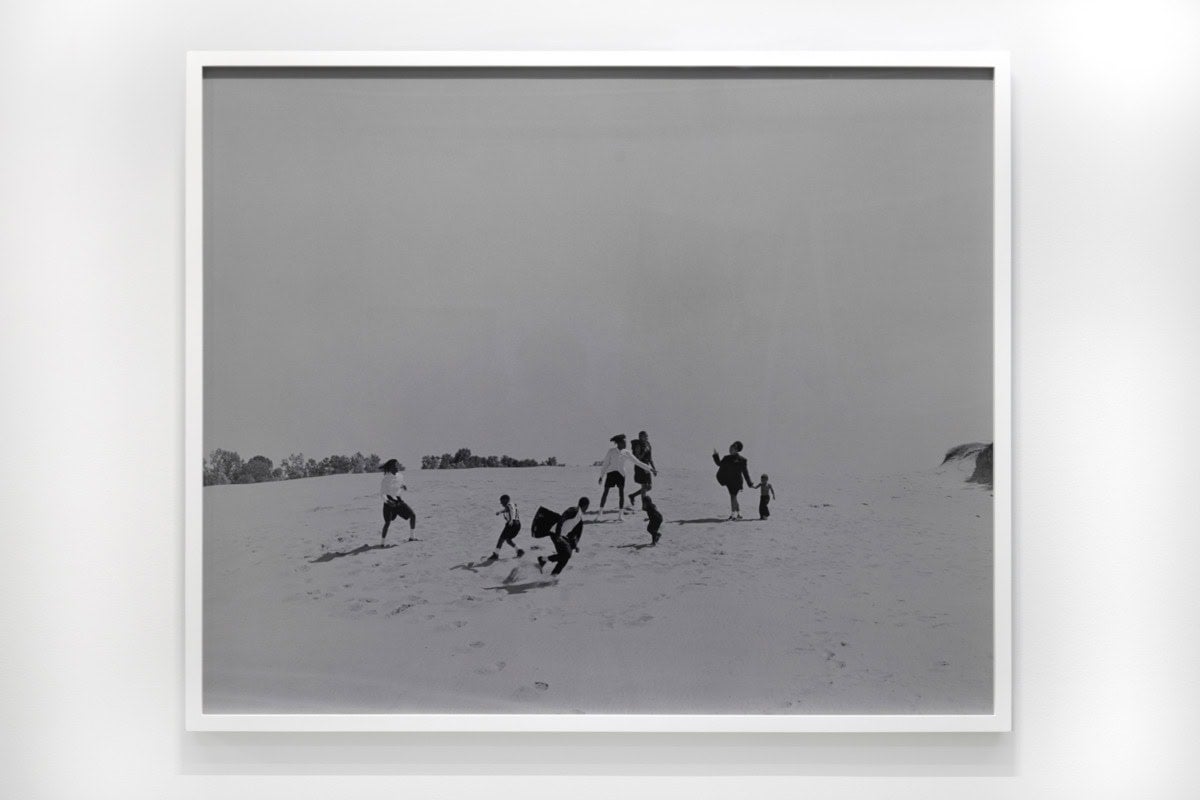

One of the first images in Tyler Mitchell’s solo exhibition Dreaming in Real Time at New York’s Jack Shainman Gallery is a nearly panoramic photograph appropriately entitled Vastness. Fully covering an alcove in the Chelsea gallery space, it depicts three groups of people standing on the plateau of a sand dune. Silhouetted by the sky and sharp black-and-white clothing, the image is one of Blackness in repose as the seemingly familial units take photographs of themselves and play with the young children present in the scene. The sand dunes suggest a far-off, arid locale, but the photograph was taken in Albany, GA, about three hours south of Mitchell’s hometown of Atlanta. The dunes are a stand-in for the sandy shores of Georgia’s Atlantic coastline, but the inclusion of this unexpected landscape serves to “[challenge] any sort of fixed ideas of what the South and/or Georgia looks like,” Mitchell told me via email.

Dreaming in Real Time leans into these contradictions, subverting these fixed ideas of Southern life and turning them into a level-headed but sweet meditation on home and family. During the first coronavirus waves in the Spring and Summer of 2020, Mitchell found himself quarantined in Brooklyn, NY––far away from his family and friends in Georgia. This period of separation caused him to meditate on his hometown and all its sociopolitical idiosyncrasies, struggles, and joys, all of which were brought into sharp focus by the unfurling pandemic. When he was able to finally reunite with his family in 2021, Mitchell began making the photographs that comprise this exhibition.

The idea of home and family consumes Dreaming in Real Time, most notably in the choice of subjects. Most of Mitchell’s compositions feature groups of people in various states of leisure and intimacy, and these interactions are heightened by the fact that a majority of the models are friends and family members. The love is palpable, such as in Connective Tissue where a drooling child sits on their father’s bare chest. Yet, the underlying tension between the socio-geographic context of these scenes and the lived experience of Blackness in the South turn the photographs into a meditative exercise on Southern duality––that home can simultaneously be a place of support and oppression.

In Mitchell’s lens, ordinary scenes of family and everyday life in a Black Southern context take precedence and are presented with grandeur. Take Group Hang, for example: six teenagers sit under a ragged tree in the brush. The shade of the tree shrouds these friends in cool darkness with only small shards of light peeking out from between the tree’s branches. In the distance, an overgrown and empty lawn roasts in the Georgia heat. The silhouetting and positioning of the group give the image a sense of cinematic reverie, as if the photograph were a still from a coming-of-age movie.

This cinematic quality is carried through Dreaming in Real Time. Nap is a nostalgic image of two young lovers’ intertwined legs on a picnic blanket, creating a composition where the sexuality of the scene is implied rather than shown. Tag, You’re It! —the only black-and-white image in the exhibition––feels plucked from a lost home movie with its composition of frolicking children on the Albany sand dunes. When we corresponded about the exhibition, Mitchell noted that film is a near-constant inspiration for him and this series was influenced by films such as Cane River (1982), La Piscine (1969), and Lovers Rock (2020), which he watched while working on the exhibition.

In addition to Mitchell’s interpolation of film aesthetics, he also uses visual cues to explore––and over the course of this exhibition, redefine––the ways in which systematic racism warps the Georgia landscape. Georgia Hillside (Redlining) is a large-scale composition depicting five groups of people arranged on a supernaturally green hill, a cloudless blue sky above them. At first blush, the image suggests leisure and pastoral joy: a young boy runs with his kite, a couple relaxes on the grass, and a trio of women dressed in finery chat amongst themselves. Yet, separating the groups are spray-painted red lines, trapping them in their own corner of the photograph.

Mitchell says these red lines are meant to literally represent the practice of redlining, the racist sociopolitical scheme designed to segregate urban areas by denying Black people the financial means and support to move into more prosperous (predominantly white) neighborhoods and school districts. The practice, while technically illegal, is ongoing in the South, particularly metro areas such as Atlanta and Charlotte.1 As a continuing symbol, the lines function, Mitchell says, as “a way of photographically showing the psychological effects of this systemic denial” of rights brought about by redlining. Yet, he says that these lines are also multifaceted as “[they] also start to divide the compositions of the photographs playfully and create entirely new compositions for the eyes to travel across. And (it is my hope) that upon further inspection and upon sitting with the work, the lines transform into potential pathways of connectivity amongst the people in the images. The people photographed are in their own zones, enjoying their own sense of leisure, belonging, and solace with the land.”

The complexity and duality of the line motif carries on throughout the exhibition in pieces such as Chalk which features three teenagers hanging out on a concrete basketball court, chatting and relaxing in beach chairs while they sun themselves in the irrepressible heat. These figures are separated by a similar pattern of red, nebulous lines as in Georgia Hillside (Redlining), but here, they help to highlight the individual character of each sitter. For anyone who has also wasted away in a Southern summer, the subjects’ oscillating expressions between sluggish discomfort and relaxation are familiar, and the drawn-on lines allow the viewer to digest the image figure by figure. Yet, the lines carry a heavier weight in the presumably urban asphalt setting where redlining has trapped generations of Black people in a cycle of systemic and oppressive racism.

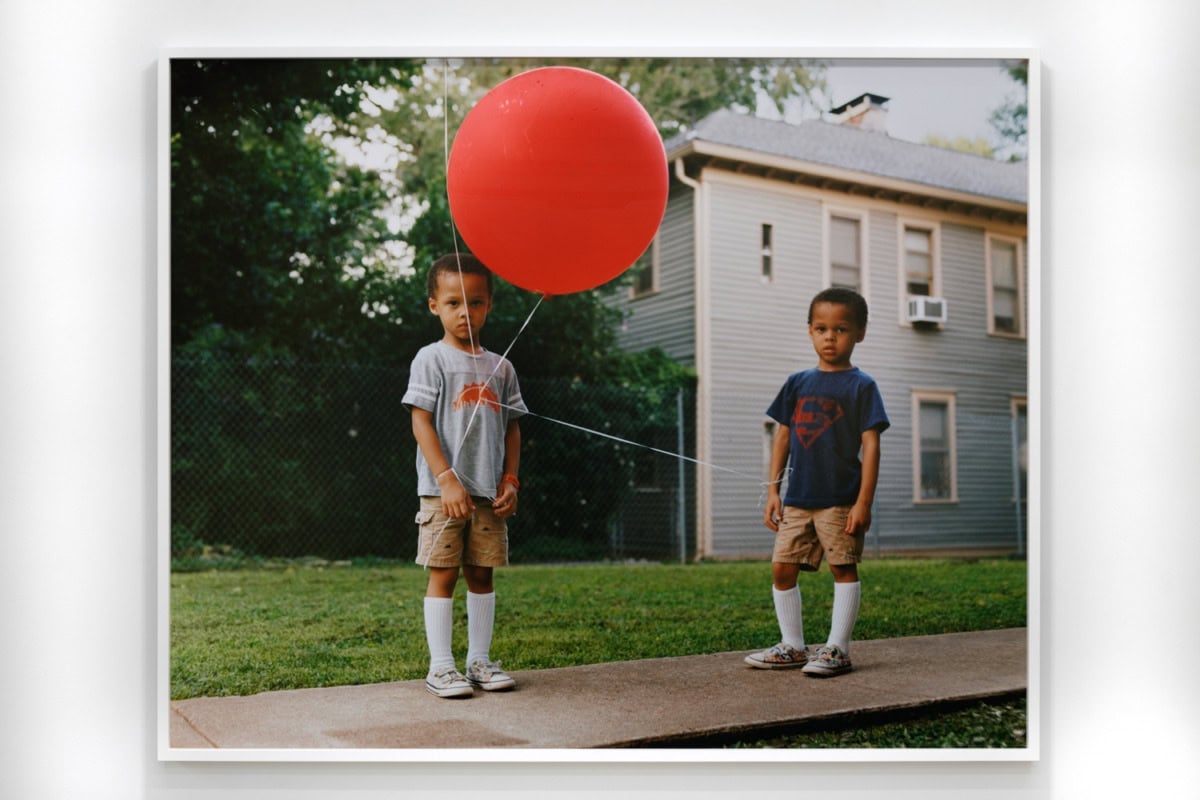

Mitchell’s transformation of the line––or at least, exposure of the line’s complexities as a symbol in his work––is best achieved in the photograph Tangled (2021), in which twin boys in front of an Atlanta apartment complex hold red balloons. Mitchell tells me that this photograph was unplanned as he happened to come across the scene while walking around the city. Here, the balloon’s string lines are tangled up, crossing the face of the child on the left. Yet, the determined stare of the child shines past the lines, and the photograph ultimately reads as both a realistic portrayal of the South’s failures and an image of hope for the future of the region.

In Dreaming in Real Time, Tyler Mitchell isn’t picturing utopia. But through his lens, he is able to craft an image of Georgia that sees home as a place of contradiction: friend and foe, refuge and chaos, love and hate. In this essential exhibition, Mitchell captures the vitality and conflict of a place defined by its past and staring down its future.

Tyler Mitchell’s Dreaming in Real Time is on view at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York through October 30th.