“I wish I had a while. Not five years, even three years—I couldn’t ask for that long, but if I had even a year. If I knew I had a year.” (xviii)

ADVERTISEMENTRaymond Carver, A New Path to the Waterfall (1988)1

My mom was diagnosed with breast cancer in her forties when we lived in Argentina, and I was in fifth grade. At the time, the malignant, ever-multiplying cells were detected early enough to treat. She engaged in an aggressive chemotherapy war and “beat” the cancer. It was as if her entire body was now a battlefield. The second time around, she wasn’t as lucky.

We had moved to New York City, and along with my father, she was so busy working and trying to save some money for retirement that by the time they detected it again, it had metastasized into what seemed like a death sentence: Stage IV cancer. I was twenty-nine when she gave me and my siblings this news, but Mom held on to life for seven more years despite her diagnosis. “Will it feel cold when death arrives?” she wrote in Spanish in one of her last journals that I found on her bookshelf, near her copy of Susan Sontag’s book Illness as Metaphor (1978). “Will death wear mittens and a jacket when she comes for me?”

When cancer knocks on the door, it destroys all concepts of self-reliance and reminds ephemeral humans that autonomy, health, and wellness only go so far. Ultimately, the probability of getting this illness depends mostly on good or bad luck, on chance. Seven months before my mother was told there were no more chemo treatments available and was recommended to start the hospice process to die at home, my father suddenly got diagnosed with a rare gallbladder cancer. Both had been healthy before their unexpected diagnosis. My father passed away a few weeks after Mom. Along with my two sisters, we took care of them around the clock as they underwent the dying process in the winter of 2021, while COVID-19 restrictions were still in place in NYC. Five months later, I found out I was pregnant with my daughter.

Every year, around ten million people die of cancer worldwide, making this illness one of the largest health problems and leading causes of mortality.2 Cancer also serves as a significant metaphor for understanding the human experience. From the pink ribbon campaigns to the triumphant, hyped-up language of war used to describe those who either “beat” cancer or “lose the battle,” there are fewer narratives shared about the grief and loneliness experienced both by patients and their loved ones after a diagnosis.

Living in Miami and raising my toddler in this city, I’ve discovered artists who similarly lost a parent to cancer. Many, like me, happen to be the children of immigrants. Their works exemplify challenging, at times experimental, art that doesn’t fit the glitzy, market-driven Miami narrative. Through conversations and email exchanges, I learned more about how these artists transformed the darkness and grief of that period into something beautiful that is worth sharing with others.

Leyden Rodriguez-Casanova

In 2009, Cuban-American artist Leyden Rodriguez-Casanova held the exhibition You might sleep, but you will never dream at David Castillo Gallery. The works came to life a year after the artist had processed his father’s death. The exhibition focused on his adolescent bedroom, which later became his father’s bedroom when he was ill. Inside the solemn space of the gallery, conceptual works are placed in a similar order as found in the bedroom. Out of context, the works may appear devoid of their original meaning, yet, a logical continuity matches the artist’s mourning. In A Bedroom Floor (2009), Rodriguez-Casanova recreates the room layout with the same tiles, now on the gallery floor, as if holding the room together. In a corner, a single foldable bed with its worn-out mattress stands closed while containing a large black rectangle as if never to be used again. In Nine Drawers Left (2009), now part of the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) collection, empty drawers from that room, separated from their dresser, are mounted to the white walls. Seemingly, all original structures of what was once home have been removed.

Rodriguez-Casanova’s parents were Cuban immigrants who had come to Miami with him in the eighties during the Mariel boatlift, and his father was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer at seventy-eight.3 “To see a man who was never sick and always working get taken down so quickly was humbling, to say the least,” he said.

Another piece made at the end of his father’s life, An Open Door (2009), exhibited at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum at Florida International University (FIU), displays a door with a black sheet of plexiglass, which appears to be the entrance into a void. “It was my processing of nothingness and the unknown,” Rodriguez-Casanova added.

A month after his father’s death, his wife and artist Frances Trombly told Rodriguez-Casanova she was pregnant. “He was the one always asking for a grandchild,” said the artist. As I continue to wrestle with uncertain ideas of an afterlife, Rodriguez-Casanova’s work mirrors my own doubts. Does a loved one stay close once they pass? Will I still see my parents again? Or does it just end here?

Gabino A. Castelán

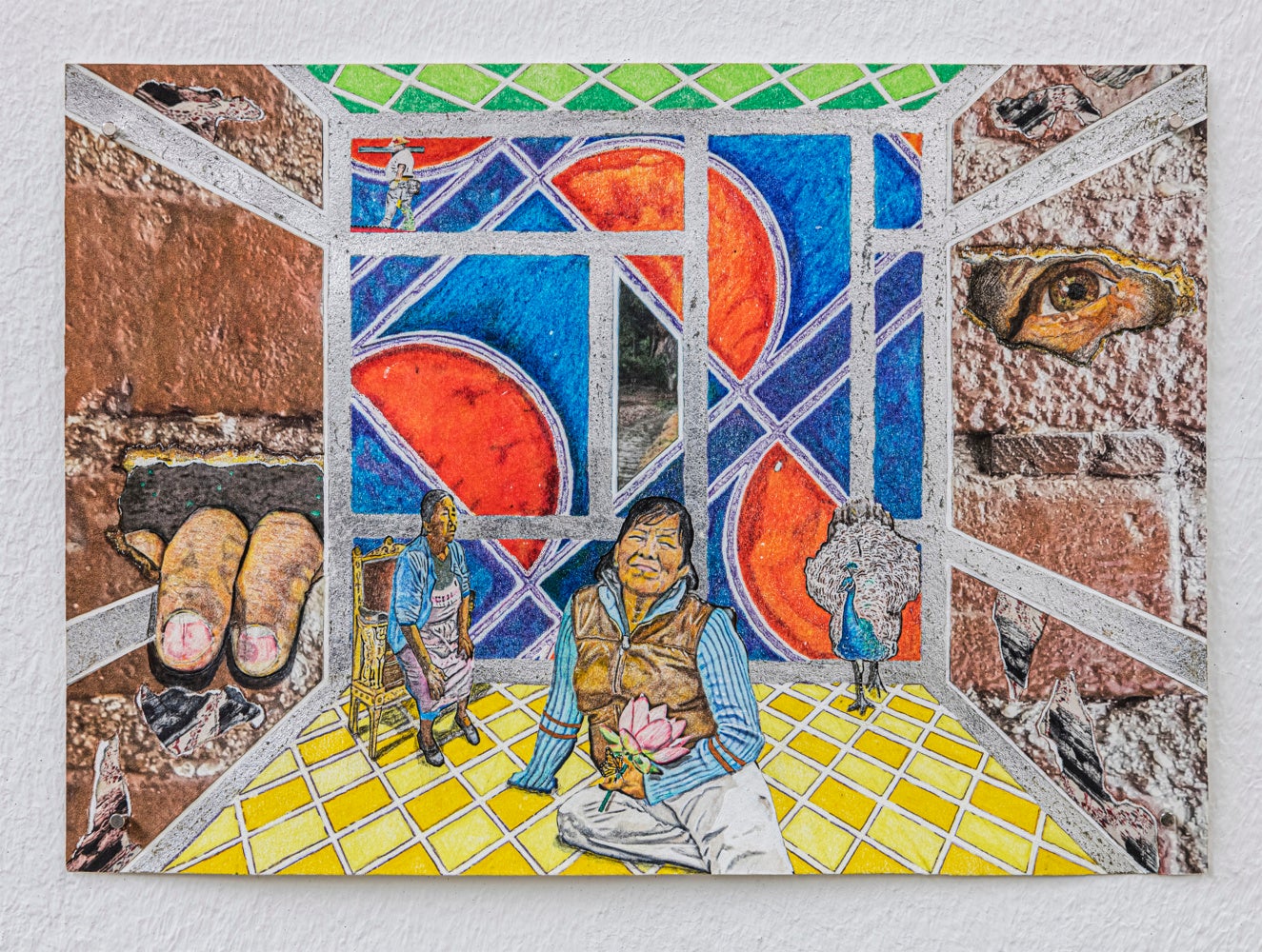

At Mahara+Co in Miami, Mexican-American artist Gabino A. Castelán’s 2023 solo show, The Dream of Ometecuhtli, displayed vibrant paintings and collage works that merged the psychic and the spiritual. The works tribute the artist’s Aztec and Nahuatl ancestry and his humble working-class origins. His piece, The Enigma of Grief: My Mother, My Grandmother, Cesar Chávez (2021), inspired by Salvador Dalí’s The Enigma of Desire (1929), digs into personal archives and Nahuatl mythology to commemorate his mother, who was born in Puebla, Mexico, and worked as a cleaning lady after she immigrated to East Harlem in New York City. She died in 2013, due to an aggressive brain cancer that paralyzed the right side of her body and took her life in less than a year. Being one of the few members of his family who spoke English, Castelán, who was in his twenties at the time of her death, took on the heavy responsibility of caretaker to support his father. “It was hard work,” he said, “bathing, feeding, translating, and taking her to doctor’s appointments. But the more complicated part was knowing she only had a few months left.”

Castelan’s works are dense with personal memory, rendering socio-political commentary about labor and immigration. Revealing the possibilities of liminal thresholds, in The Enigma of Grief: My Mother, My Grandmother, Cesar Chávez (2021), an image of the artist’s mother is at the center of this pictorial collage work. She sits on a self-contained, cosmic throne, staring at the past, present, and future generations while holding fresh blooming lotus flowers, symbolizing rising from a dark season into beauty and rebirth. Now, as a father of two, Castelán recalls this experience, “It felt like my heart was utterly destroyed, and I felt much sadness. But there were also moments of joy that my mom and I shared during her illness.”

Like Castelán, I also became a close caretaker of my parents as their illness progressed and they began hospice care. Having embarked on this journey at a younger age, I quickly realized how little the end-of-life care process is discussed. In great discomfort, many would rather leave the room than hear about the expiring of the body, nevertheless their own finitude. The job was lonely, imperfect, and full of sleepless nights, with moments of exhaustion, frustration, and tenderness.

Lanise Howard

Capturing the beauty of the transition into the afterlife with grace and dignity, LA-based artist Lanise Howard’s 2023 solo exhibition, Lanise Howard: Procession of the Son, at Mindy Solomon Gallery in Miami, was full of mystery. “I’m clairvoyant, and often I see things before they come. I’ve always been this way,” she said. Two years ago, when she started having visions of her mother passing, Howard tried to convince herself it was just her subconscious, and she continued to paint. Like her visions, Howard’s large-scale paintings lure viewers into intimate universes inhabited by the energy of life, death, and reincarnation, while offering a close look at Black male vulnerability.

In “Walks of Transformation” (2023), Howard paints Black bodies inhabiting sacred and liminal places. A group of men carrying a coffin walk together from an open door at dusk into a twilight of deeper blue hues, ultimately assembling a vast night sky. The flock of birds surrounding the hyper-realistic bodies and the lotus flowers also point to movement from one portal to another, and finally, rebirth. Howard calls these works “The casket paintings.” Heavy on purple hues, pink tones, and deep blues, the paintings were “challenging for the viewer and myself,” she explained. At the time of their creation, her mother had been diagnosed with breast cancer, the artist was only thirty years old. She later realized the piece depicted three of her brothers honoring her mother, giving her flowers, and following her home.

It was healing to experience those paintings, which appeared to be a direct, worldly translation of the artist’s visions and dreams. Maybe it doesn’t just end here; maybe there is always a new path.

Catalina Jaramillo

In contrast, Miami-based, Colombian artist Catalina Jaramillo’s 2011 installation, You Are Always Here, at Dimensions Variable Gallery in Miami, presented a tangible reality many face after a loved one’s death: What do we do with all their stuff? Using performance, video, photography, and sculpture, she showed viewers how mundane objects can become sacred once the person who owned them is gone.

The artist neatly assembled objects belonging to her mother, who died of cancer: hair color boxes, cleaning supplies, notes, hairbrushes, shoes, and rustic clothes. Jaramillo’s mother, an immigrant from Colombia, constantly talked about the decades when her family had absolutely nothing. Once in the United States, she bought many of the same items, as “they gave her a sense of having more than she did,” Jaramillo states. After her death, “all of these objects seem to be waiting to be administered as an inefficient replacement for her physical presence,” she wrote in her artist statement. After viewers navigated through this small universe of belongings, they were invited to take an object with them.

I read Jaramillo’s handling of her mother’s objects as an act of care and a call to healing.

For me and my sisters, having to close down my parents’ rent-controlled apartment in Queens in less than two weeks was the opposite of that. We were rushed and not ready. We took what we could with us, but we had to throw out so much of the material of their lives. It felt devastating.

***

Seeing these artists transmute the darkness of loss into tangible, sometimes luminous, artworks, I wonder if they walk lighter now. I cannot deny that my experience of witnessing two loved ones undergo the end-of-life process has made me carry death with me in ways that still feel heavy. I think of the passing of time, how many years I might have left to care for my own children, and how life might feel to those who are told they only have a few months left to live. I am also aware that illness and dying isn’t equitable for communities of color and those in conflict zones, which face disparities in access to healthcare, and a dignified death. These stories are deserving of additional conversation and expression.

Seeing these artists transmute the darkness of loss into tangible, sometimes luminous, artworks, I wonder if they walk lighter now.

Poet Audre Lorde, who went through a fourteen-year cancer journey before meeting death at fifty-eight, writes, “Living a self-conscious life, under the pressure of time, I work with the consciousness of death at my shoulder, not constantly, but often enough to leave a mark upon all my life’s decisions and actions.”4

Maybe, with that consciousness of death waiting at the door, ready to knock anytime, is how I chose to live life too.

[1] One of Raymond Carver’s last journal entries as quoted by his long time partner, Tess Gallagher, in the introduction to his book of poems written before his death to lung cancer. Raymond Carver, A New Path to the Waterfall, (Place of Publication: Atlantic Monthly Press 1988), p. xviii.

[2] Kendall K. Morgan. “How Many People Die of Cancer a Year?” Accessed September 10, 2024, https://www.webmd.com/cancer/how-many-cancer-deaths-per-year.

[3] The Mariel Boat Lift is known for the massive movement of over 125,000 Cubans from the port of Mariel to the shores of South Florida in 1980. https://guides.library.miami.edu/mariel.

[4] Audre Lorde, The Cancer Journals, (London: Penguin Classics, 2020), 9.

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Knock Knock.