I was not expecting fresh carrot juice, the discovery of my new favorite hot sauce, and a delicious homemade lunch on October 12, when I pulled into the secluded driveway that leads to performance artist and poet Maggie Ginestra’s new Roswell retreat. I was to find all of these things and more inside her rented cottage and studio space in a surprisingly suburban choice of neighborhood. Once on the property, I understood why Ginestra would leave the closeness of her friends and arts community in Atlanta’s Grant Park; she needed the quiet to reflect more deeply, the room to define her identity more sharply, and the time in seclusion to keep reinventing her current reality.

Ginestra is appreciated as an artist and organizer who champions collaboration, a poet whose words are just as arresting as her performance of them, and for a mysterious reserve of creative spirit that appears limitless. This all comes in a package of fashionable attire, a shock of short platinum blonde hair, and an angelic face with delicate features. Over lunch, we discussed Ginestra’s multifaceted artistic endeavors; her identity as a poet and the role of technology in her live readings; the definition of loyalty; and an exciting, upcoming residency in March 2014 with her boyfriend, performance artist Mike Stasny, at MINT Gallery .

Sherri Caudell: You’re originally from South Florida, not Atlanta, right?

Maggie Ginestra: Yes, but I grew up thinking about Atlanta as this mecca of familial fun—my god-family and cousins lived here. As an only child, it’s the place I got to go to be with people. The High Museum was the first museum I ever went to. Atlanta was a place of positivity for me. I do loathe the traffic; I don’t know how to occupy my mind while in a car. People are good at making plans for their day or listening to NPR, but I get bored and mad. I turn off the radio and just sit in the misery of it.

SC: Do you identify as a poet?

MG: I feel like alone, I’m a poet, but I’m not interested in just working alone. I’m an extrovert who’s an only child. I grew up having a lot of time to narrate to myself to make sense of things—I live somewhat in my imagination.

SC: How do you reconcile fantasy and reality?

MG: Reality and fantasy are large and need to be broken down, which happens through aggressive, obsessive listing. I have a book where the top half is my day, and the bottom half contains poetry or art ideas, these terms being synonymous to me.

SC: Tell me about Stirrup Pants, the chapbook shop you ran in Saint Louis.

MG: I went to graduate school for poetry at Washington University, but I didn’t stay in academia to teach. As I was leaving graduate school, I discovered the world of chapbooks, but you could only read about them online to decide if you wanted to buy one. I thought, “That’s insane, I want to touch all of them and think about them.” I moved to an art district in Saint Louis and lived above a little storefront. I went to the Association of Writers & Writing Programs Conference in Chicago with a card and said, “I’m going to start a chapbook shop. If I did, would you give me books on consignment?,” and everyone said yes. In 2010, I curated a selection of chapbooks in the front room and had a “Saturday Salon” in the back where people would come in, look at chapbooks, and have free snacks and drinks. After the shop closed, Amelia Colette Jones and I collaborated on Sloup, a program that grew out of the shop.

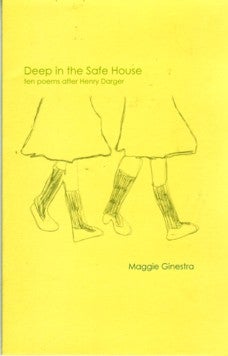

SC: It’s cool that it was a physical space where people could experience the books as objects. Your first chapbook, Deep in the Safe House: Ten Poems After Henry Darger,was published by Dancing Girl Press in 2008. Are you working on a new book?

MG: I wrote that when I was 20 and felt like a student of poetry, trying to be good at something. I’m as insecure now and striving just as hard, but that striving feels a lot wider. I haven’t made a book in a long time; it’s not a goal. My goal is to keep writing, making things, and participating in conversations.

SC: The poems in your first chapbook focus on relationships, boys, and being a girl. Are you still working with the same themes?

MG: Yes, there’s a never-ending reality of being a girl; and boys still exist, and so do relationships. Most of the sex and kissing in my poetry is fictional. It’s easier to play with intimacy on the page. I use the body as a canvas for thinking when I write. In my writing, touch keeps resurfacing—it doesn’t have to happen in a poem, but I like for it to. My recent reading at Emory University for the What’s New in Poetry series, curated by poets Bruce Covey and Gina Myers, felt like performance art pretending to be a reading.

SC: I attended, and your poetry resonated with me. Your format is fresh in the way you utilize technology as a vehicle for your writing.

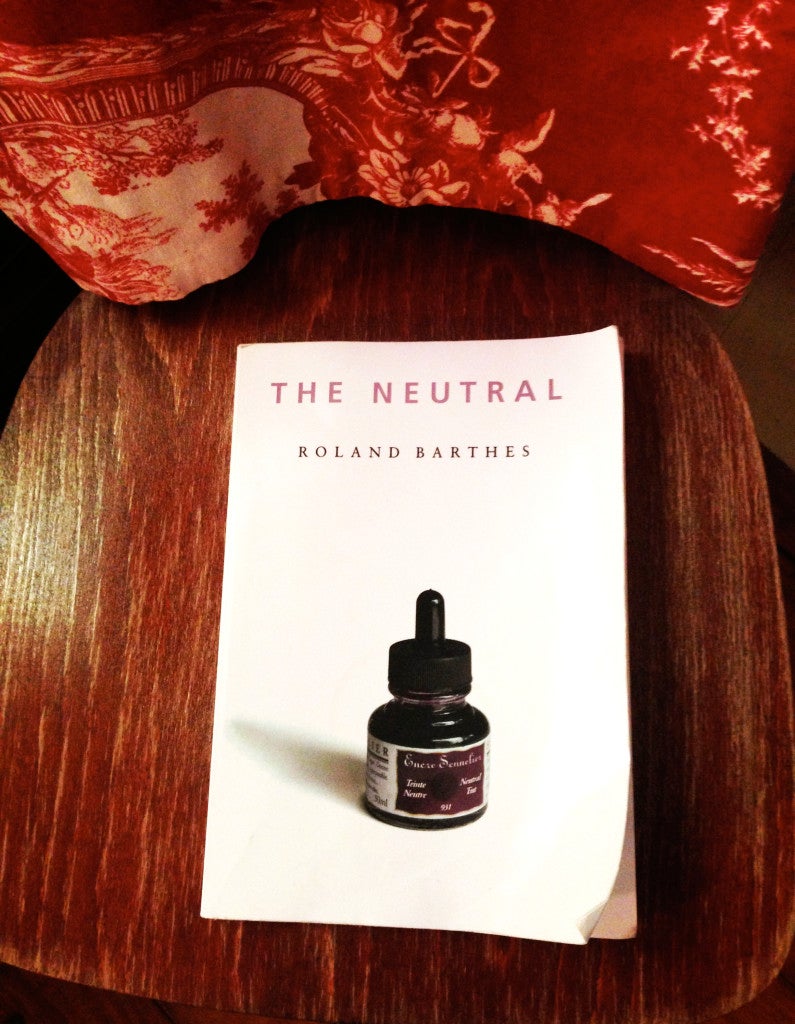

MG: The piece was a result of researching the concept of loyalty and what it means, in the context of friendships, in dating someone for three years, and in trying to be committed as a writer. I explored the idea that after you’ve loved someone for 10 years the concept of duration becomes more real, fascinating, tricky, and awesome. I’m anxious that I’m not honoring everything that’s given me a gift in life; it’s a fear of not being kind enough. The answer I found was Roland Barthes’s The Neutral, which is the core concept of his last series of lectures he gave before he died, which I discovered while reading Maggie Nelson’s book The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning.

SC: Could you expound a bit on the use of technology during the Emory reading and how the idea presented itself?

MG: I was thinking about text messaging and how much it’s a part of my life in conjunction with loyalty. I was considering the lack of privacy and the way we value each other because of smartphones. You can imagine someone isn’t thinking of you if they don’t text. There’s a feature on Google Chat and iPhone that allows you to see if someone’s writing you back, and then sometimes the typing symbol goes away because they’ve stopped writing. There’s intimacy in a letter arriving, and privacy in sending a letter. Nobody has access to the moment you wrote it or walked to the mailbox. There’s also privacy surrounding the moment the other person receives and reacts to the letter. No one has access to the way the person is experiencing that communication in time. I want to feel alone in my experience of time and text messaging violates this by collapsing space and time. I texted my audience jabs of truth during my live reading, as they were experiencing the atmosphere of my voice, language, and story.

SC: Did you set up a number for the audience to text?

MG: My phone never communicated with my audience’s phones. When I told them I had done something to give myself the capacity to text them, I was lying. I paid to subscribe to a website called Ez Texting and I bought the name “IWILLBELOYAL,” which is the title of the poem I performed. The audience was asked to send a text to 313131, Ez Texting’s phone number. I prepaid enough so that no matter how many people showed up to the reading, I’d be able to reach them. I was reading first that night around 8 PM, so I preprogrammed a cycle of seven texts, minute-by-minute, from 8 to 9 o’clock. I didn’t know what the exact timing of the live event would be in relation to the texts, so I enjoyed how that made me think about what I wrote.

SC: Were the texts we received taken from the poem that you were reading aloud?

MG: Not exactly. I was reading excerpts from my writings on loyalty. I’d never done a reading before this, where the persona was just me, Maggie Ginestra, no facade. In Deep in the Safe House, I’m imagining I’m one of the girls in a landscape by the artist Henry Darger, so I’m not quite myself. The texts that I sent during the reading are promises to my reader—my response to Barthes’ “twinklings.” One text was: “I will designate the hour for compliments.” Barthes had this meditation on the danger of compliments—“When you compliment someone, you hold them to a thing, you name them in this way”—so he’s sort of anti-compliment.

SC: Do friendships inform your work?

MG: Yes, highly! I’ve never had a lover or a best friend that I didn’t want to collaborate and create with. Often the music or the books I find and my curiosity in general is married to the curiosity of the people around me. If I’m going to hang out with you, you’re going to sort of define my reality. The people I spend a deep amount of time with are on similar quests as me. I want to be enriched and pushed. I love being a musician, a director, an actor, a performer, or an organizer in a collaborative setting. I’m good at listening to people’s creative impulses and becoming the second part of it. There’s an organizational, curatorial, or just curious energy that I bring to a project. But I hope that by the time we’re in the collaboration, it just feels like play. My boyfriend, artist Mike Stasny, and I have done a couple of performances in Atlanta, in correlation with his art moniker MSIF Presents. In Saint Louis, we’d do performance art where we were creating a dance party atmosphere, choreographing dancers, and designing site-specific installations.

SC: Why did you leave Grant Park and come to the suburb of Roswell? It is like a writer’s haven out here with the creek, land, and nature.

MG: Mike and the owner George Long decided to share a studio space. We knew this cottage was here, and the woman who was living here decided to move. I thought, “This is amazing,” because we struggle with space. In Saint Louis, it was really cheap; we lived in an enormous warehouse by the river and threw epic dance parties. I had a huge kitchen where I would be infusing tequilas and then be making felt in another area, and Mike’s creating monsters in a different part of the warehouse and on the roof. I had my special writing desk. And there was still a bunch of empty space—it was wonderful.

Then we moved to Atlanta, to a little apartment in Grant Park, where Mike was making his monsters in the middle of the living room and I was writing in a corner. Even though our new space at this cottage is small, it’s my studio and I’m frequently alone in it. I wait tables at Gunshow at night and Mike works mostly with Souls Grown Deep during the day, so we’re usually not here at the same time. I spend my days at this table: just writing, working, thinking, reading. Suddenly we both have all the space in the world we need to think separately, which gives us the energy to want to collaborate again.

SC: What projects are coming up?

MG: I helped textile artist Aubrey Longley-Cook with his RuPaul embroidery workshop and cross-stitch animations while working at WonderRoot. We were thinking about community projects and how his practice might document the local drag scene in Atlanta. He decided to do a workshop at WonderRoot, where he invited participants to help make an animation of RuPaul, which will be part of his show opening in December at Barbara Archer. I and 35 people each made a frame, which he’s going to photograph in succession to make the animation. I can’t wait to see the results of all our stitching.

I’m also working on a long-term collaboration in Saint Louis, with Agnes Wilcox, the artistic director of Prison Performing Arts. In 2008, we worked with the Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts and Washington University to invite former prisoners and homeless veterans to create a performance in response to an exhibition. I helped develop a script based on the actors’ ideas about the artwork. We recorded them, transcribed their thoughts, and made excerpts. A general audience watched as they performed in front of the artwork. It went well in 2008-2009, with the Staging Old Masters exhibition, so we did it again in 2010-2011 with Staging Reflections of the Buddha, both at Pulitzer. Agnes and I applied for a local grant in Saint Louis, so we could write about how these people transformed themselves and the audience, what that transformation meant, and what their process was. We’re hoping to have a draft by April 2014 and to do another project later in 2014 with a different museum, perhaps with a focus on contemporary art.

SC: Do you have a working title for the book yet?

MG: Performing Seeing: A Theory and Methodology. It’s the idea of performing what you see.

SC: When will you and Mike perform together next?

MG: We’re doing a month-long residency at MINT Gallery called Sumptuary [March 20-April 21, 2014.] Sumptuary taxes are taxes on goods that might be “sinful,” like cigarettes or booze. We’re going to run a bar at MINT and ask for suggested donations for food and drink, which will act as “sumptuary taxes” that will fund a series of over 20 arts projects. These will include installations, performances, and happenings that will take place in the gallery over five weeks.

SC: Your personal style seems to play a role in your expression as an artist—I find it striking.

MG: I feel like I’m watching style through layers of fuzzy glass. I have a memory of being in an airport when I was four years old and looking at a woman’s hands and her long and graceful fingers. I was so excited that I was going to have hands like that someday, but now I still have little girl hands. I think style feels the same way to me; it’s mysterious and I have a yearning for grace. I’m wearing what I want to wear, but I think buried in it is a little girl who’s looking at these hands, at these long fingers. My relationship to objects is very sharp: I like a thing or I don’t. I have strong opinions and some of that is inherited from my mother. She’s either fiercely sentimental about an object or doesn’t care about it at all. I don’t have a lot of things, but the things I have, I’m fierce about.

SC: Do you consider yourself a feminist?

MG: I feel like a gendered human with a gendered imagination. There are all of these male and female things inside of me, all these zeros and ones, building out everything all the time. Sometimes I feel like a pretty androgynous creature, sometimes I feel like a very female creature. I really struggle over this stuff. I’m a feminist, and to be a feminist is to acknowledge the reality of gender. So to say you’re not a feminist, is to say you’re not interested in how gender is a part of reality—the ways it can oppress or enhance, and how it can own space and interaction.

People who are not feminists are not curious. The act of writing is the yearning to feel empowered. I start writing from this decentered space that’s often a gendered moment for me, where I’m feeling female in the negative sense, as in not my whole self but half of myself. I’m reaching toward wholeness through writing and that feels like a feminist effect.

SC: Are there moments when you achieve that “wholeness”?

MG: Absolutely, but not in the way that “I wrote well,” just that I sat down and did it.

Listen to Maggie Ginestra’s poetry reading from September 12, 2013, here.