Over the past year, museum and cultural workers in New York City have won important victories on the job. Workers at the New Museum, the Tenement Museum, and the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) voted to form unions with UAW Local 2110, and workers at the Guggenheim Museum voted to join the International Union of Operating Engineers.

It wasn’t easy. In response to their employees’ desire to unionize, administrators at the New Museum and the Guggenheim hired expensive “union avoidance” law firms. These firms specialize in legal wrangling to minimize the number of workers deemed eligible to join a union and in trying to scare workers out of voting to form one. Bosses at BAM sent emails and conducted one-on-one meetings to try to discourage workers from voting to form a union.

New Museum worker Lily Bartle told Jacobin that her bosses “told us things like, ‘Unions create divisions that weren’t there before between employees,’ and ‘Unions build walls where there were none.’ But thus far the campaign has actually bridged a lot of the gaps that were built into the institutional structure of the museum, and there has been an incredible amount of solidarity across virtually every department of the museum.”

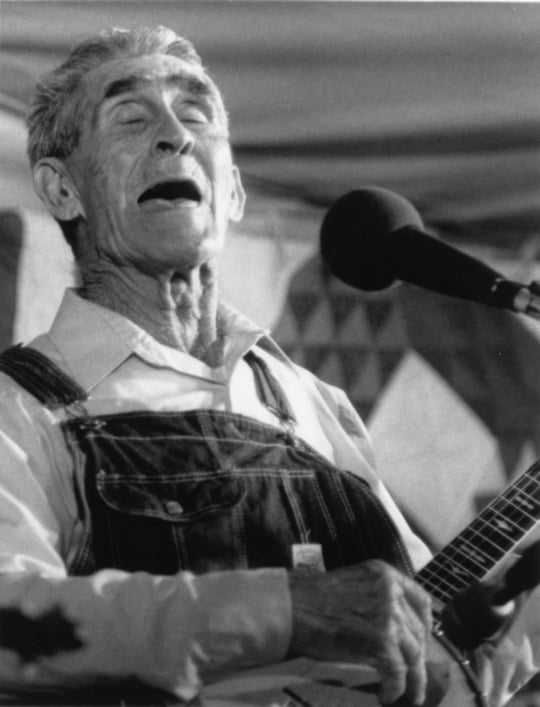

Local 2110 president Maida Rosenstein said in an interview that museum workers are often drawn to the sector because of a “sense of mission.” But museum bosses and anti-union lawyers they hire weaponize that same feeling against workers who want better conditions. “They say, ‘You’re lucky to even work in this place.’ It’s a prevalent mentality that people absorb. But we have an old slogan—you can’t eat prestige,” Rosenstein said.

While workers at all four institutions voted overwhelmingly in favor of unionizing, there is still a lot of work to do. The four new unions still need to negotiate and ratify a first union contract—a task often as difficult as forming the union, if not more so.

But they have reasons to be hopeful. Last year, workers at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)—who have had a union for years—won a new contract with significant pay increases. They were also able to beat back major concessions on health insurance costs that MoMA heads wanted to impose on employees.

The number one issue for museum workers? “Compensation is a huge issue, especially in the context of the cost of urban living,” Rosenstein said, on museum workers’ motivation for forming unions. “They thought there would be a sense of shared mission, but they had a rude awakening about how that shared mission only goes so far when the upper echelons of the museum administration are making very high salaries and the boards are largely made up of extremely wealthy people. Meanwhile, workers are eking out a living, struggling to make ends meet while these institutions rely heavily on their dedication and skill,” Rosenstein said.

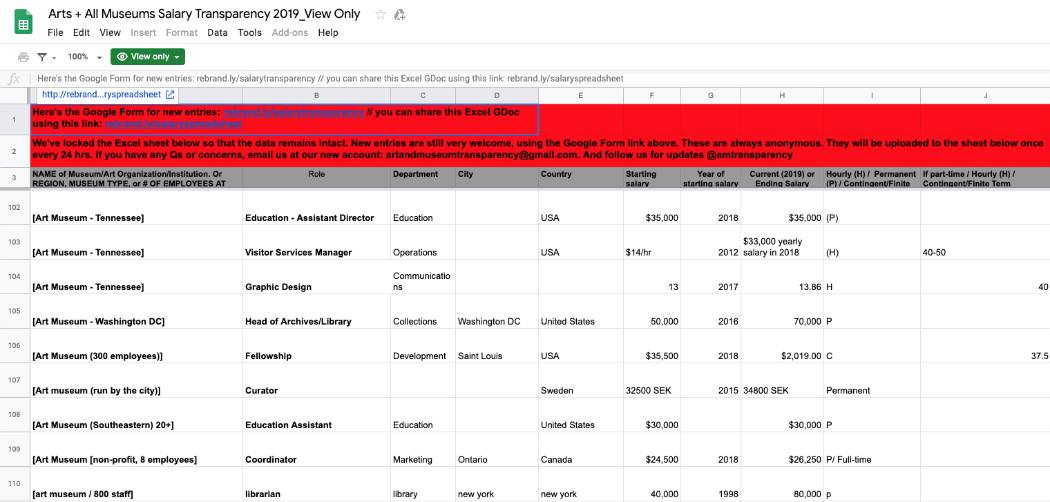

That’s true all over, not just in New York City. Art and cultural workers from across the world have flocked to a public spreadsheet developed by the group Art + Museum Transparency, with self-reported pay, health benefits, parental leave, and other information from more than 3,000 workers.

“It was a group project from the very start. [The initial organizers] shared our salaries. We all have terminal degrees, low pay, and low job prospects. I still feel quite nervous a lot of the time,” said Michelle Millar Fisher, a member of Art + Museum Transparency. The group has refined the spreadsheet over the past several months, adding and adjusting questions based on feedback from users.

Art + Museum Transparency has also heard from many arts workers who say the spreadsheet has encouraged important conversations with their coworkers. “If you talk about it with your coworkers, you can organize for better conditions. No one else is going to do it. Your future is in your hands,” Millar Fisher said. But given that the recent wins have all occurred in New York, a city with high union density, pro-union laws, and a long history of strong unions, can they be replicated in other parts of the country?

Among the biggest barriers to organizing unions are “right-to-work” laws, which are on the books in twenty-six states, including every state in the South. Designed to weaken unions, right-to-work laws mandate that workers receive all the benefits of a union-negotiated contract even if they refuse to contribute dues the union needs to function. Since some people will always be happy to freeload—reaping the benefits unions bring without contributing—unions in right-to-work states tend to have fewer resources than those in other states.

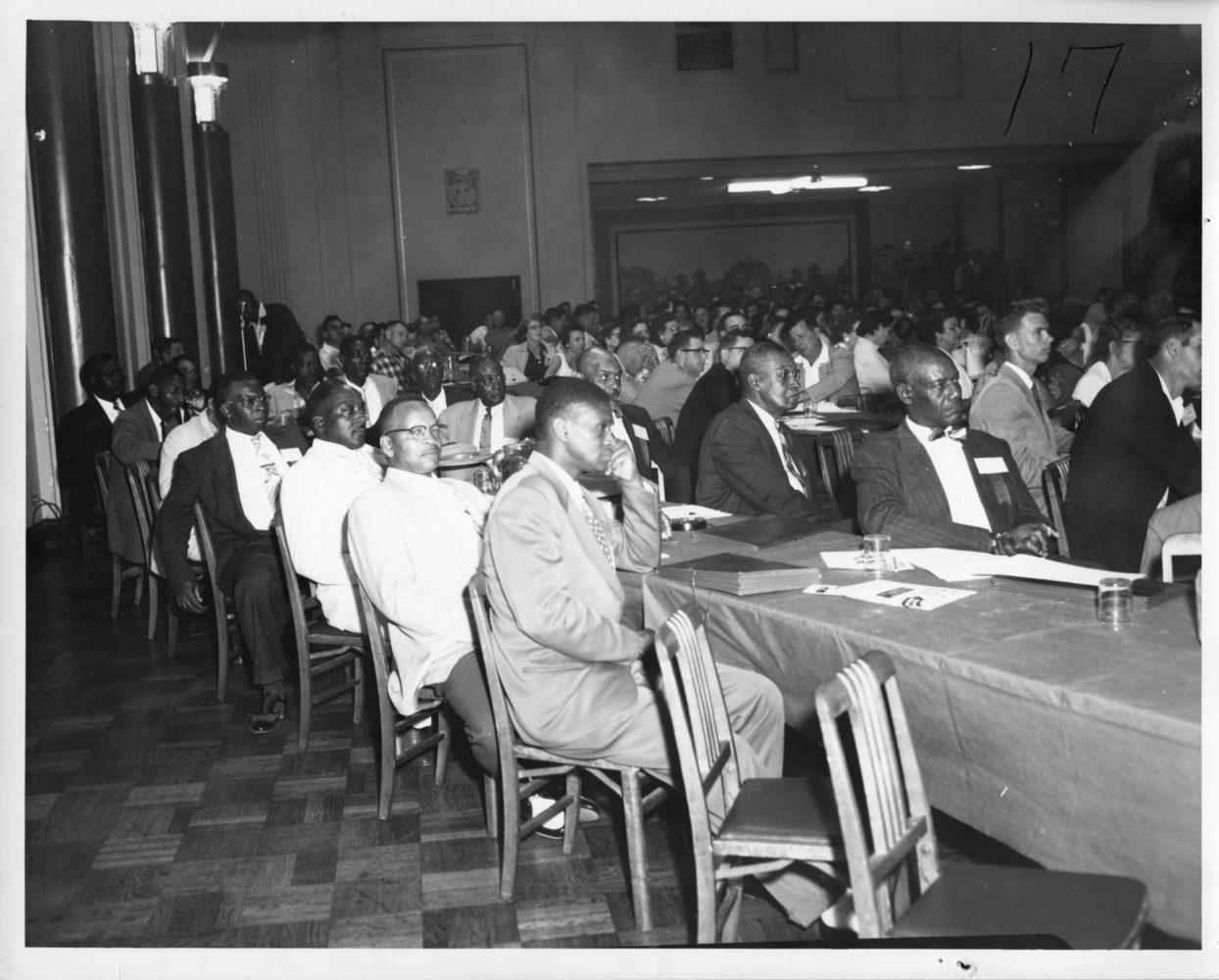

Right-to-work laws originated in the South in the 1940s as part of an explicitly racist, anti-Semitic campaign to prevent unions from gaining strength in the region. Anti-labor lobbyist and right-to-work architect Vance Muse publicly insisted it was critical to “protect the Southern Negro from communistic propaganda and influences.” Other pro-right-to-work literature from the period warned that if the proposed state laws failed to pass “white women and white men will be forced into organizations with black [sic] African apes . . . whom they will have to call ‘brother’ or lose their jobs.”

While Muse worked almost exclusively in the South, he took money from both Southern and Northern companies eager to prevent organized labor from gaining strength. It worked. State-level right-to-work laws swept through the South and other parts of the country in the 1940s and 50s, and another wave of laws passed in the 2010s. Muse was long dead, but big business and wealthy conservatives had learned in the meantime how effective right-to-work laws were in keeping wages and benefits low, even if they dropped the overt racism by then.

According to a Bloomberg analysis, there were far fewer new unions formed in right-to-work states than elsewhere. Objectively, it is more difficult to form a union in the South than in other parts of the country where workers have greater legal rights. Does this mean any potential art worker union is doomed to fail in the South? No. While the laws may be stacked against workers, the fundamental factors that drive workers to unionize are as present in the South as any other part of the country—perhaps more so.

As elsewhere, art workers in the South make barely enough to get by. As elsewhere, they’re told to be thankful for having the “prestigious” job at all, whatever the sacrifices. As elsewhere, millionaire donors give massive sums for new buildings or galleries museums can name after them, but high-paid supervisors can’t seem to find it in the budget to give their staff members a raise.

As Art + Museum Transparency has shown, just talking with your coworkers about your shared experiences can lead to important points of unity you never knew you had. For the vast majority of art workers, trying to improve conditions on your own is not a realistic path forward. One or two junior workers just don’t have the power on their own, but a group of them does. Finding out whether other people at your job share your concerns is the first step towards making things better. What’s the alternative? A lifetime eating prestige?

This story is part of our collaborative series with Scalawag exploring art and labor in the South. Read the previous installment—Madeleine Seidel’s essay for Scalawag on the radical Southern labor film tradition—here.