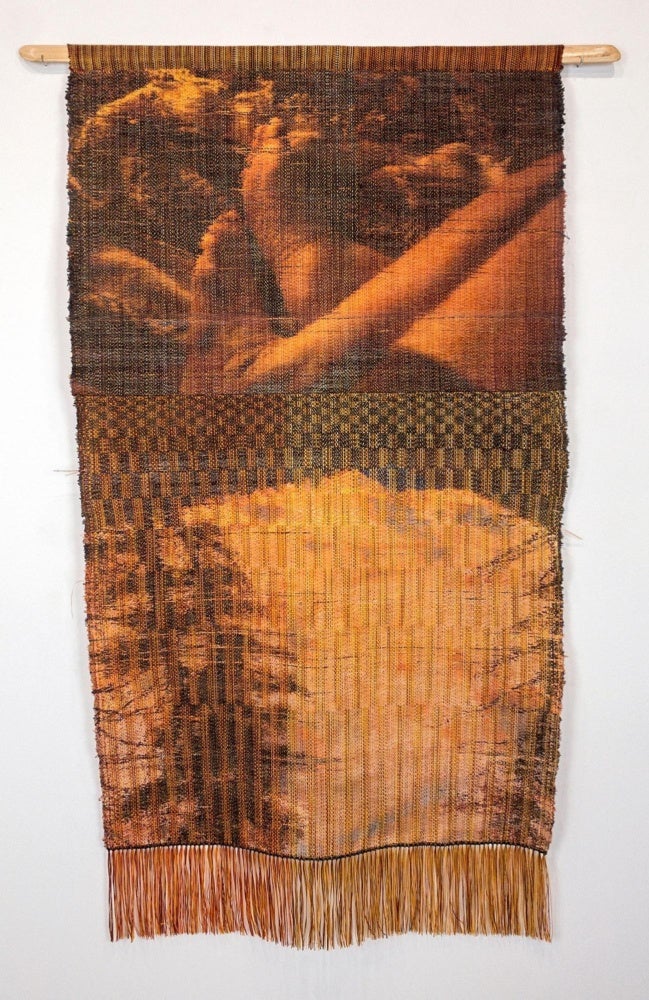

In the foothills of Appalachia, a foggy mixture of growth and decay permeates the atmosphere, where earthen scents are deep and primordial. In Night Picnic: Firelight Flag (2025), a body appears suspended in amber—preserved in crystalline stillness. With feet curling and flexing from graceful limbs, bathed in warm ochre, Elysia Mann weaves an intimate portrait of human form through delicate, melodic thread.

As a young girl on a homestead in Nebraska’s Umónhon territory, Mann navigated a rare congenital childhood eye disease that rendered her right eye blind (she describes it as a “dead eye”). Fearful of complete vision loss, Mann tethered herself to her environment by fixing her gaze upon the Nebraskan plains’ vast horizon—an act that a yoga practitioner like herself call the drishti, or conscious seeing. By focusing on an external object, one can cut through distractions and connect with the physical world. This practice concentrates energy and awareness, revealing the body’s limits and the nature of sensory perception. With one conventionally functioning eye she can not ‘triangulate’ space in the same way as those with binocular vision; she can’t perceive depth in the conventional way. Rather than viewing this as a deficit, Mann harnessed the ability to rest comfortably in doubt and uncertainty, discovering that this liminal space is where wonder and curiosity truly lie. Drishti created a sense of spaciousness within her body and a connection to the land.

The convergence point of land and sky became her anchor, both boundless and constant. While living in Florida, she found a visual touchstone where coastline meets sea, offering another expansive horizon to ground her vision. However, these clean horizons of Nebraska and Florida burst into a new harmony upon the undulating, sinuous edges of the Smokey Mountains, where Mann presently lives and creates. In Appalachia’s untamed landscape of forest and kudzu, winter days contract beneath the mountains’ looming silhouettes. In this darkness, as night itself became a new kind of horizon, Mann attunes her process to time’s slower rhythms, opening her work to the quiet possibilities of shadow. At the loom, she works with gentle and tedious care in quiet opposition to consumer culture’s demand for speed and to capitalism’s demand for mass-produced novelty.

Mann’s handweaving connects directly to Appalachian craft traditions. While she obtained her MFA from University of Tennessee, Knoxville in 2017, her studies at Penland School of Craft in 2017, 2022, and 2023 link her to an institution founded by Lucy Morgan in 1929 as Penland Weavers. Initially a cottage industry providing local women with looms and materials, it emerged during the craft revival movement sweeping Southern Appalachia, a movement that was as much about cultural preservation as it was about economic justice.1 Though weaving has often been mischaracterized as a tool for confining women to domestic spaces, Penland illustrates its legacy as a collaborative practice fostering economic independence, social solidarity, and political resistance. Under Morgan’s vision, what began as a cottage industry blossomed into a powerful vehicle for artistic innovation, allowing women to transform traditional skills into avenues for creative expression. As Mann stands in an ancestral lineage so rooted to place and practice, her movement around the loom leaves its signature in every thread—a dance of creation where feet press treadles to lift weft and warp, hands guide thread through thread, and the body moves in constant rhythm. As art historian Madeleine Mitchell writes regarding the history of Appalachian weaving, “The structure of weaving itself indexes the movement of a woman in the act of creation.”2

In Playing Position (2023), Mann makes this bodily indexing literal—like an afterimage burned onto the retina. Two hand-shaped yellow textiles rest on grid paper, which in turn lies atop a textile fragment to create a layered record of presence. It signifies the engagement of her hands upon the loom, plucking string and thread to form a haunting, melodic visage—a conductor in this dance of creation. It this an intentional engagement with slow looking and slow creation—experiments with time—that allows Mann to create striking and distinct textiles that hover between the abstract and figural. “Slowness leads to entanglement,” she writes.

The translation warps like an analog glitch, reminiscent of other material mutations: garbled meaning in poetic translations; a miraged oasis on the steaming desert horizon; or misinterpretation of an embroidery code.

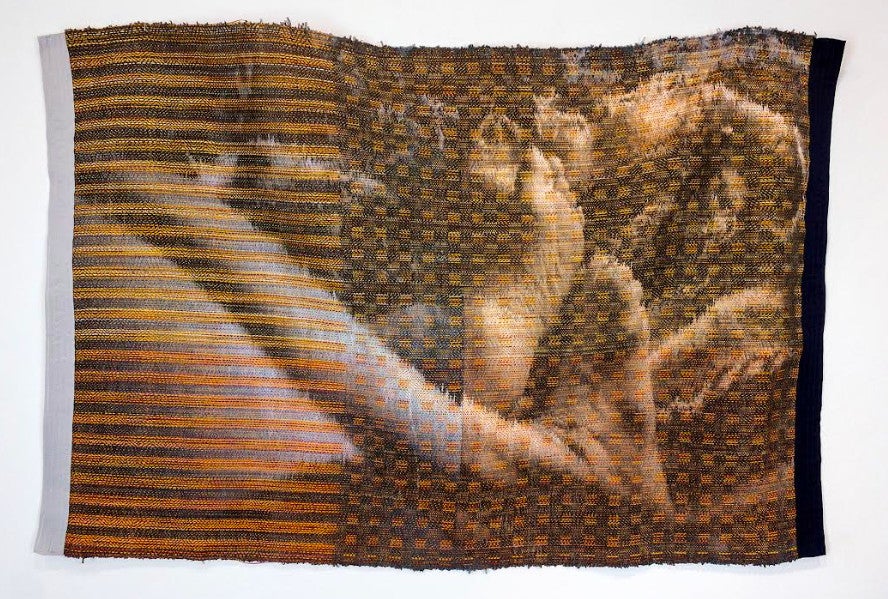

This enmeshed vision finds expression in her We Am series (2017) of doubleweave tapestries, which combines the methods of printmaking and weaving. Mann screen prints yarn with fiber reactive dyes before working it into the loom. Using two warps allows her to double the printed image, though she can only see the top layer as she weaves. In How to Be Twice (2017), the effect is one of simultaneous dissolution and reformation—a watery, mirrored silhouette of an abstracted body that resists precise duplication. The translation warps like an analog glitch, reminiscent of other material mutations: garbled meaning in poetic translations; a miraged oasis on the steaming desert horizon; or misinterpretation of an embroidery code. In this glitched, abstracted body, Mann achieves what Legacy Russell describes as a refusal “to be hewn to the hegemonic line of a binary body.”3 Her work is a nonconformity to the Western ideals of beauty—that is, the symmetrical—while still cultivating homeostasis. It is clear in both Playing Position and How to Be Twice that Mann is engaged in a conscious dialogue between dualities. Her exploration of binaries serves a deeper purpose: the pursuit of integration and wholeness, even as her partial blindness complicates traditional ways of seeing and orienting. Through bilateral practices like EMDR therapy and yoga nidra, she has found mindful approaches that acknowledge opposition while working toward unity.

The thread that binds her work is this nondualist conception of existence and embodiment. In Night Picnic: Feature Show (2025), she dissolves the boundaries between body and landscape. Arranged into a vertical diptych, the upper segment mirrors Firelight Flag from the same series: feet curled vulnerably, suggesting an unseen body. The legs extend into the lower segment—a flipped photograph of the Appalachian mountains that transforms into multiple bodily readings. The mountain’s gentle slope becomes a bowed back, its protruding ridge a spine. Tree silhouettes slash across the frame like scars along ribs, while an expanse of sky opens like the hollow of a womb—a space of potential creation.

Ultimately, Mann’s woven works resist simple categorization, instead occupying the fertile territory where opposites meet and dissolve. Through patient handwork—the rhythmic dance of shuttle and thread—she maps a visual philosophy that challenges the tendency to separate self from world. Her art reminds viewers that boundaries between sight and blindness, body and earth, self and other are ultimately permeable, fusing into a wholeness that is rooted in the land of Appalachia.

[1] “History of Penland School of Craft,”Penland School of Craft,” accessed February 2, 2025, https://penland.org/about-us/history/.

[2] Madeleine Mitchell, “Looming Large: Coverlet Weaving in Southern Appalachia,” in Canvas: https://www.canvasjournal.ca/read/looming-large.

[3] Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (Brooklyn, NY: Verso 2020): 11.