The act of consuming images is a constant negotiation between perception and reality. Art allows me to traverse these realms, to retreat into a world where I seek solace and space to dream; writing about art becomes a sanctuary where I am absorbed by the stories of artists and their life’s work. When in museums and galleries, I relish slow looking, poring through the details beyond the work itself among curatorial statements and wall texts. Yet, there are moments when the peaceful sanctuary in my mind’s eye becomes disrupted, as if a large door has violently swung open and slammed shut, ushering in an unannounced visitor. On these occasions, a detail within an image or a work of art will permanently take up residence in the recesses of my memory, like a missing puzzle piece that lies dormant until additional context can help me complete the image. The opening line of “Afterimages”, Audre Lorde’s 1981 poem, expresses this phenomenon:

However the image enters

its force remains within my eyes[1]

In “Afterimages,” Lorde describes the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955, and how the searing image of the murdered Black child in his open casket bored itself deep into the author’s memory, reappearing decades later after she watched a news segment about a flood in Mississippi in 1970. I have considered similar images that have taken residence in my own mind. Early one morning in 2021 while scrolling Instagram, I came across a photograph posted by the artist Simone Leigh. The picture is of a young Black woman sitting for a studio portrait in the late 1800s. She’s wearing a floral, cotton dress that’s cinched at the waist with a solid sash, her elbows rest on the velvet arm of a parlor chair as her arms extend upward with her hands clasped to one side, cradling her left cheek. Her motley crown of disheveled plaits is in contrast with the starched, crisp, pressed fabric of her dress, suggesting a hint of spontaneity to the portrait setting. Next to the young girl, a lone sunflower towers over her head. The ceramic vessel containing the flower’s stem is a face jug; its menacing visage, punctuated with an arched eyebrow, taunts the viewer with eyes directed squarely at the camera lens. A delicate ostrich feather fan lies at the end of a table, just out of reach of the subject’s arm, from which a long chain dangles, its attached horseshoe resting on her thigh. The presence of this one odd accessory gave me pause. In some cultures, a horseshoe is considered good luck, but my visceral response strayed far from thoughts of fortune—here, the object felt more sinister. Its presence turned what appeared to be an anodyne portrait into something else; this was the nudge I needed to prolong my gaze. The girl’s sullen eyes now came into focus, and my chest felt tight. Through a more contemporary lens, I could dismiss her blank affect as adolescent insolence or indifference, but the sadness in her gaze feels palpable. The moment I saw the image, it took up residence in my mind’s eye, lying in wait for me to find answers to the many questions the photograph summoned. It has haunted me ever since.

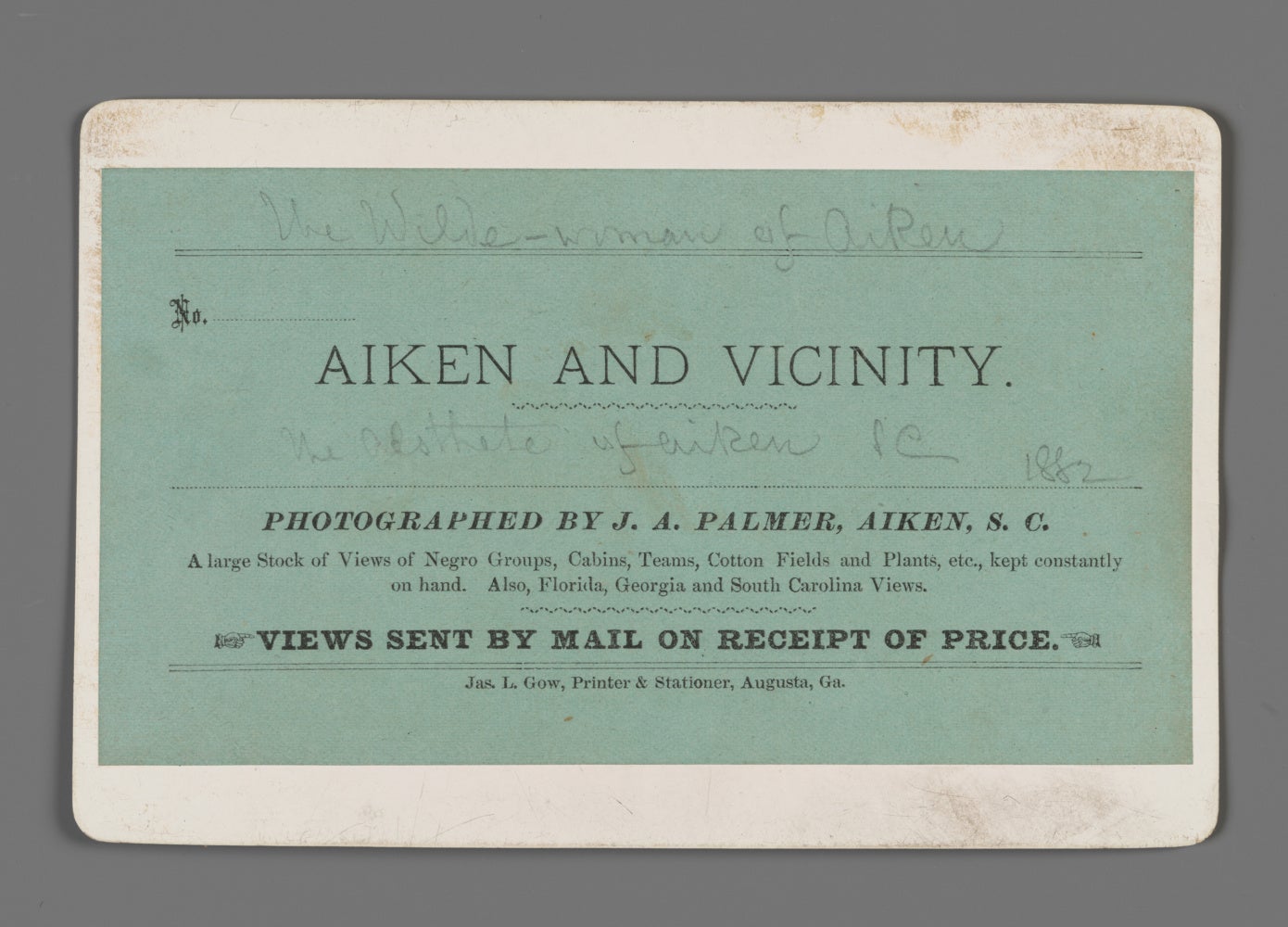

I revisited the image online months later and noticed the title inscribed on the back of the photograph: The Wilde Woman of Aiken. The picture was one of a pair of photographs taken in 1882 by J. A. Palmer of Aiken, South Carolina, and originally created as a satirical attack on the Irish poet Oscar Wilde[2] These photographs had two goals: to discredit Wilde’s controversial ideas around the aesthetics of beauty and to cement racist ideologies around Blackness and beauty. To wit, Palmer turned the poet’s signature accoutrements, including sunflowers and ostrich feathers, into stereotypical tropes that countered Wilde’s definitions of beauty and mocked his sartorial style. This form of satire was de rigueur for publications like Harper’s Bazaar, who depicted Wilde as a monkey and other subhuman life forms, caricatures that were also weaponized during Reconstruction to chip away at the social, political, and economic advances that African Americans achieved post-emancipation.[3]

Palmer’s propagandistic portraits were sold as postcards and distributed in the same manner as lynching photographs and other racist ephemera that reinforced Jim Crow violence while giving a new shape for the commodification of the Black body. Similarly, the image’s caption, The Wilde Woman of Aiken, perpetuated hypersexualized archetypes of Black women as objects of sexual desire. We do not know the identity of the young woman in this photograph, who Palmer refused to name; instead, like the sunflower and the face jug, her status is relegated to that of a photographic prop. In the absence of her identity, I have wondered how we can reclaim the subject’s memory, resisting the temptation to create a sanguine counternarrative, in favor of dismantling the scaffolds of fear and loathing that supported the widespread circulation of these racist tropes.

The practice of critical fabulation, a term first coined by the cultural historian Sadiyah Hartman, acknowledges the gaps between the prevailing historical archive and the lives of those erased by it. It’s an exercise in correcting the canon, one that “may be the only available form of redress for the monumental crime that was the transatlantic slave trade and the terror of enslavement and racism.”[4]

In her rumination of this process of writing against the archive, in an essay titled “Venus in Two Acts,” Hartman acknowledges the precarity and theoretical landmines that exist around this important work as well as the desire for these narratives to be retold. Nevertheless, she writes, “the loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them. So it is tempting to fill in the gaps and to provide closure where there is none.”[5]

Yet there are artistic fabulations that satiate my need for redress and reconstitution. I ultimately located these missing puzzle pieces through prose and clay from the writer Robin Coste Lewis and Simone Leigh. Together they present The Wilde Woman of Aiken a new light, one that releases the subject from the grip of Palmer’s gaze. Lewis dedicated a poem to The Wilde Woman of Aiken, summoning the young subject’s inner voice. In the first line she acknowledges the photographer’s cruel intentions:

I am not supposed to be

beautiful.

As Lewis continues, a new image emerges, one that is bolstered by the subject’s resolve to blossom. Her beauty is complemented by the sunflower that sits next to her.

I am the Fourth Sister.

My florets stand together

at golden angles. My head

is packed with eager seeds

crisscrossing in spirals

one hundred garlands long

Through poetry, Lewis creates a power shift that restores the subject’s agency. The sunflower is also known as “the Fourth Sister” in gardening circles due to its function as a protective barrier when planted next to bean, corn, and squash crops. It’s also a symbol of new beginnings, optimism, and promise. Lewis authoritatively summons the power of the land to protect the Wilde Woman as she wrests narrative control away from Palmer in the last line of the poem:

You

cannot

prevent me

Leigh picks up visually where Lewis leaves off. Her 2022 sculpture comes full circle with the image she shared in 2021. With seeds planted and the girl’s destiny claimed, Leigh casts The Wilde Woman of Aikenin a new light, setting her on a transformational journey that begins with nineteenth-century craft traditions rooted in the Carolinas. Leigh renders her in white porcelain, glazed with a sheen that evokes a sense of regalness.

The girl’s hoop skirt takes the shape of a larger-than-life jug, which forms the base of the sculpture. It is similar to the face jug that Palmer featured in his photograph, which is coincidentally the earliest documented image of the distinctly African American form of pottery that hailed from Aiken’s neighboring town of Edgefield, South Carolina. Edgefield was the home of the pottery traditions borne out of slavery and artfully perfected by David Drake, also known as “Dave the Potter.” While enslaved as a potter and in defiance of laws that restricted literacy, Drake learned to read and write, finding solace in poetry. Through verses surreptitiously inscribed on the vessels he created, Dave the Potter asserted the voice he was denied. Poetry and pottery became his only routes to freedom, a path metaphorically and figuratively replicated by Lewis and Leigh in their work.

In Leigh’s rendering of the subject of Palmer’s photograph, the girl appears slightly older, and her hair resembles an updo lovingly plaited and molded in clay. Perhaps more important is what’s missing in the sculptural reinterpretation of the photograph. Leigh’s woman no longer carries the horseshoe; she’s now unburdened by the weight of its subhuman connotations. As with many of the artist’s sculptures, Leigh presents a face without eyes. The omission feels explicit here—the viewer is denied access to the subject’s gaze. Leigh’s signature detail is well suited to combat the racist residue of the original photograph. Lastly, she releases another burden from the subject, relinquishing the title that placed her and Wilde at the center of ridicule. The piece is simply named Anonymous; while her identity remains unknown, the woman is no longer a satirical spectacle. By cloaking her in anonymity, Leigh removes the power of others to name her.

The moment I saw the image, it took up residence in my mind’s eye, lying in wait for me to find answers to the many questions the photograph summoned. It has haunted me ever since.

Through their work, both Leigh and Lewis free the subject of Palmer’s photograph from the violent grip of its origins and create a new afterimage through the imagination. When Leigh shared Palmer’s photograph on Instagram, she didn’t explicitly state its role as source material. Rather, for me, it became the first puzzle piece and a powerful prompt. When I see Palmer’s photograph, I am reminded of its capacity to tell a fuller and deeper story, and driven to acknowledge the work of Lewis and Leigh that deconstructs this history. As the writer Leigh Raiford notes, “Memory is an active process.”[7] Within Lewis and Leigh’s reconstruction of memory, the subject has found redemption. “Survival comes in the retelling,” Raiford writes. The afterimage, or memory, of The Wilde Woman of Aiken, the Fourth Flower, and Anonymous doesn’t recede or fade. It evolves, revealing itself in a new light, as other pieces of the complex puzzle of history bring the surroundings of the subject’s reality into sharper focus. This process of remembering and re-remembering, expanding the critical aperture, remains an essential tool of resistance and imagination.

[1] Audre Lorde, “Afterimages” (1981), from The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde (New York: W.W. Norton Company), Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42582/afterimages.

[2] Victoria Dailey, “The Wilde Woman and the Sunflower Apostle: Oscar Wilde in the United States,” Los Angeles Review of Books, February 8, 2020, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-wilde-woman-and-the-sunflower-apostle-oscar-wilde-in-the-united-states/.

[3] Dailey, “The Wilde Woman and the Sunflower Apostle.”

[4] Saidiya Hartman, “On working with Archives,” interview with Thora Siemsen, The Creative Independent, April 18, 2018, https://thecreativeindependent.com/people/saidiya-hartman-on-working-with-archives/.

[5] Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2: pp. 1–14.

[6] Robin Coste Lewis, “The Wilde Woman of Aiken,” in “Poems from Sanctuary,” Transition, no. 109 (2012): pp. 33–42. The following excerpts from this poem are from the same source.

[7] Leigh Raiford, “Photography and the Practices of Critical Black Memory.” History and Theory 48, no. 4: p. 12.