We’re eating peaches and drinking red wine while I sort through a massive stack of four by six photographs, and Andrew Lyman tells me about one of his new lovers. “My new definition of art is something that would look good in his bedroom,” Lyman says. He means it. I understand completely.

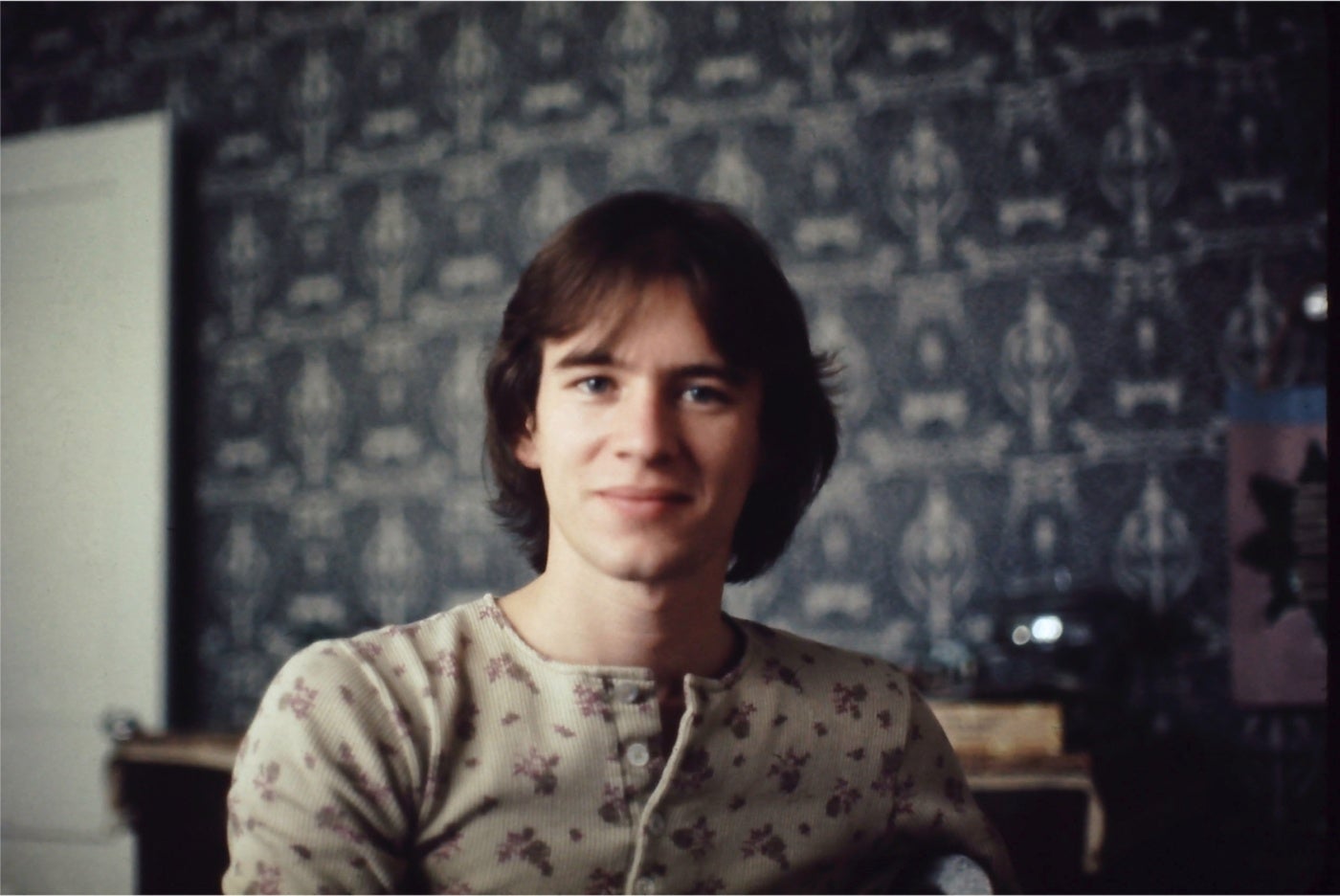

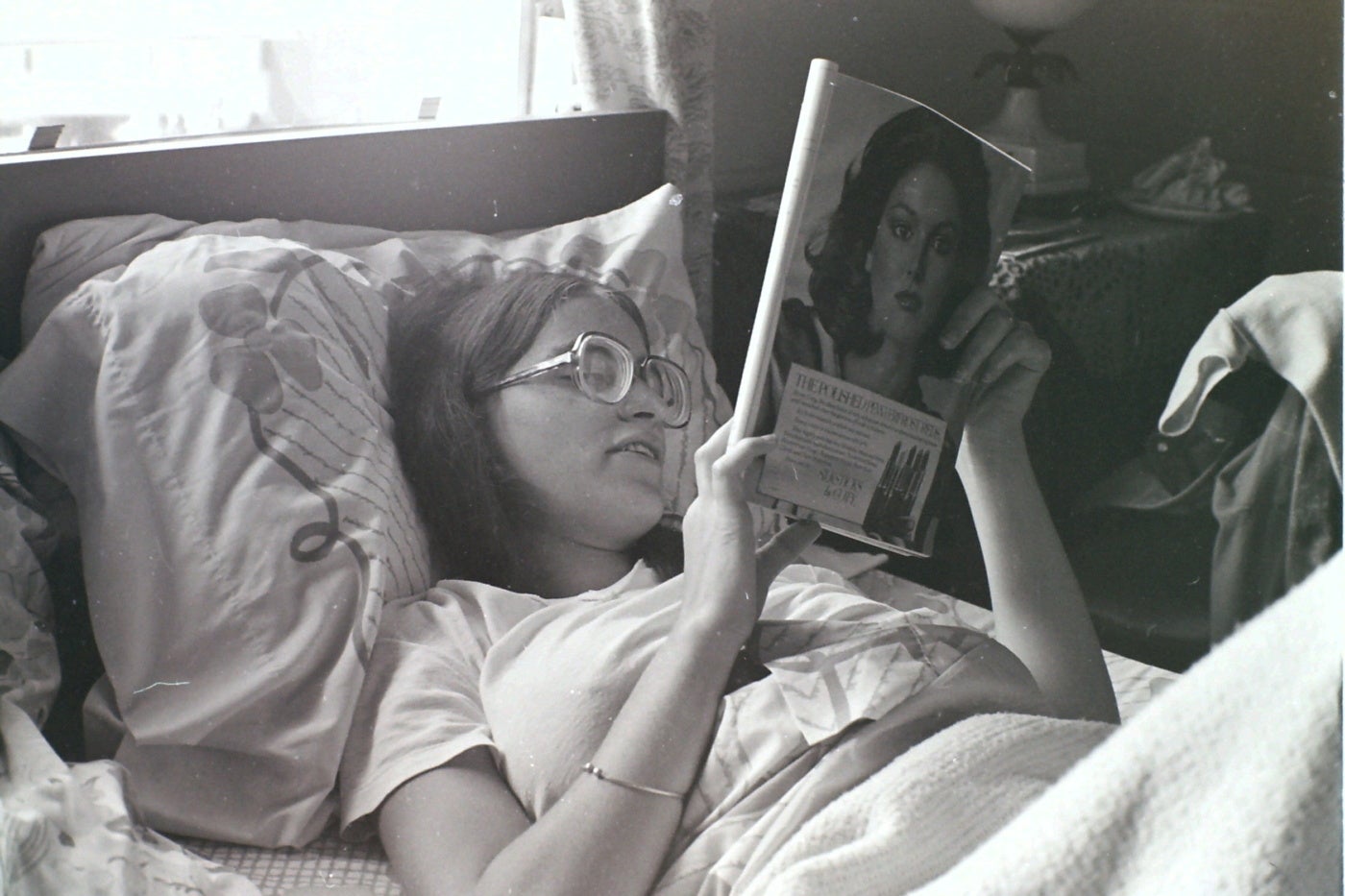

Lyman’s photographic work is highly romantic. Half-nude subjects pose languidly across beds and couches, bodies dappled in evening or morning light, eyelids relaxed. Friends embrace and drink and dance in a shallow river, sunshine sparkling off the water and through the tree leaves. One-night stands are promoted from fleeting encounters to Renaissance-esque portraiture. A thin gold chain rests on a lover’s neck. Beneath the sunlight and sweat and soft affection is something deeper. There’s an obsession and a relentless optimism to capture not only the feeling of being newly in love, but something Lyman calls “the impossible nowness.” This desire to prolong the honeymoon into eternity isn’t a naivety for Lyman; rather, it’s a philosophy and subtle act of rebellion.

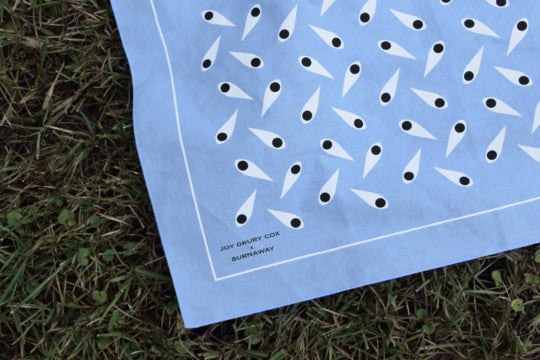

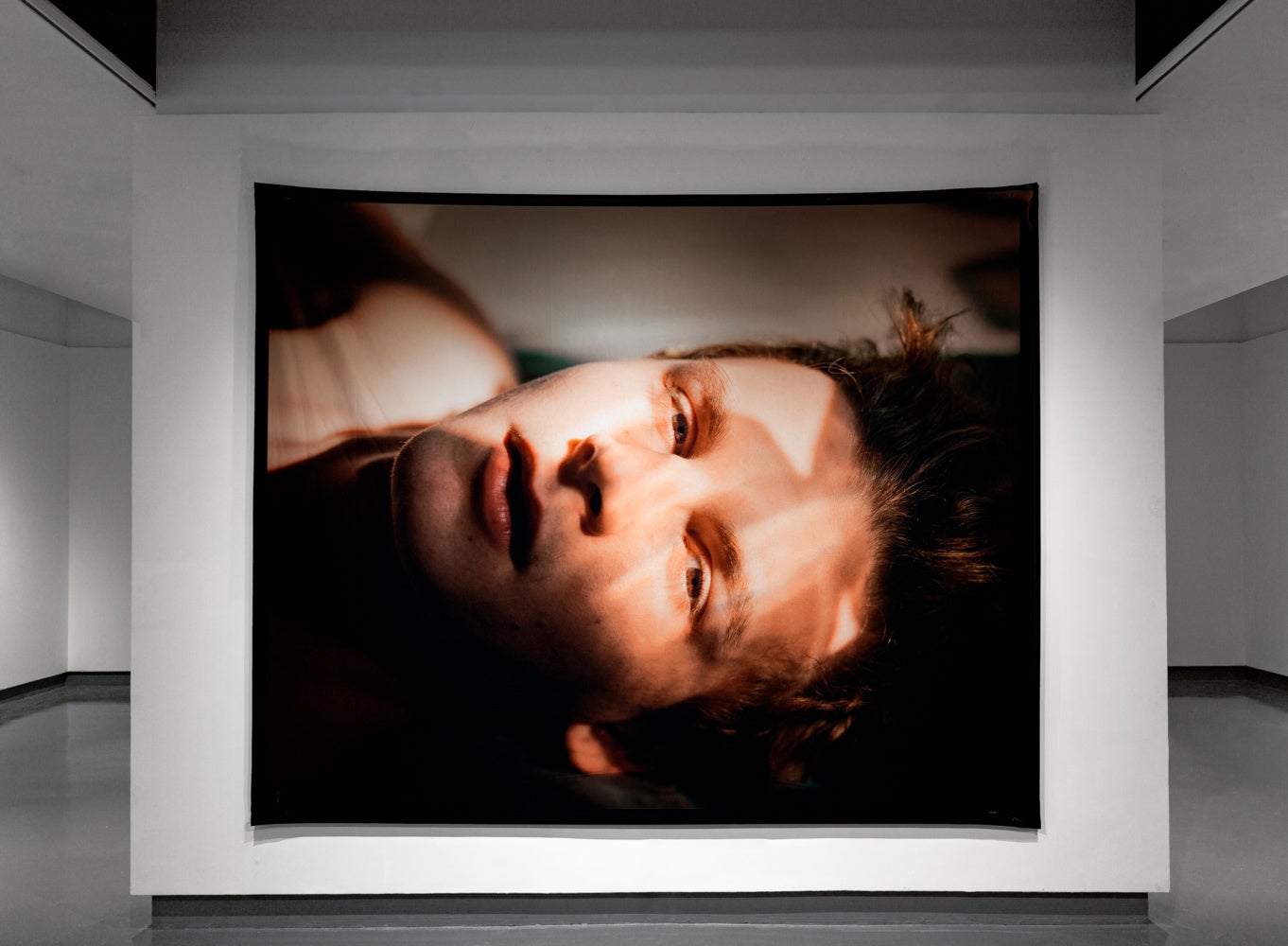

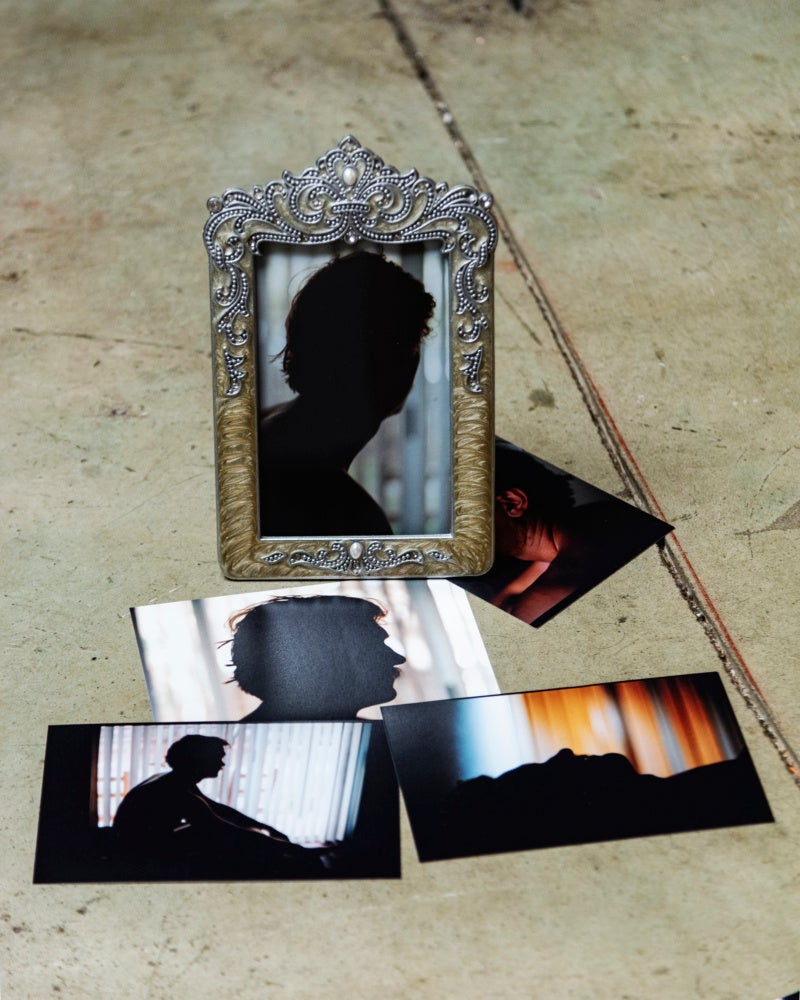

A critical element to Lyman’s practice is his ability to present his work in a way that draws in the viewer not only visually but emotionally. His frequent use of decorative picture frames, which for younger generations are most often associated with a kind of grandma-style, nostalgic era of family photo displays, instead, serve to immediately endear the subject to the viewer. This heteronormative nostalgia is then subverted by Lyman’s depiction of queer relationships and institution-breaking social structures. When not employing the decorative frames, Lyman may blow up images to epic proportions, creating massive fabric photographic installations that magnify every detail of a person’s face. The large scale reinforces importance and transmutes the feeling of intimacy from the artist to the viewer.

Of course, there’s hazards involved with centering your art practice around loved ones. Friend groups dissolve and heartbreak happens. The photographs left behind are an archive of sorts, moments in time of moments of hope. Their value has not decreased, but their emotional charge inevitably changes. This risk does not sway Lyman’s impulse. At our studio visit we talked about how to manufacture intimacy, the influence of family photos, and how aliveness comes with a heightened sense of mortality.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

E.C. Flamming: Intimacy and fantasy, often mixed with your own memories and experiences, are common elements in your work. Do you think intimacy can be manufactured?

Andrew Lyman: I think we all manufacture intimacy all the time. It’s like going on a date—we’re going to a restaurant, we are wearing special outfits, we’re rising to the occasion to make it work. For my practice, photography is just one of the elements that’s on a date. And it sometimes makes the connection happen, like that’s the container for it. It’s lovingly manufactured. My photography is one of the characters in that arrangement. I get pictures out of it. The pictures are the thing. The pictures are where we meet in that moment. It’s like playing Bananagrams. We’re different people when we play games. I’m a monster with Bananagrams.

ECF: You display your work in unique, considered ways, such as the small decorative glass frames that you might find at a thrift store or the large-scale fabric portraiture. How do you approach presentation in your work? How do you want your work to be experienced?

AL: I want people to feel how I’m feeling. I want people to know the pictures the way that I know them. And with the huge fabric print, I’m like, how can I recreate being so close to this person’s face? And being able to see every detail and the thrill of having access to them. And the frames cultivate a sort of nostalgia, familiar and established, and then challenges it in a way. People know how to feel about four by six pictures. Well, maybe not my students anymore [laughs]. But people know how to react to photographs when they’re printed on four by six, like there is that patina that the film has and soft focus from particular cameras.

ECF: Could you talk about how you first got into photography?

AL: I first came to know pictures through my dad’s photographs of the family. I’m the youngest of three. My sisters are nine and eleven years older than me. I was born in 1993, so that was when we’re just seeing the end of analog photography and the beginning of mainstream use of digital photography. But my very early life and my sister’s lives were all documented and my mom and my dad’s relationship were documented in this really beautiful analog 35 millimeter film way. I always had those film pictures in the back of my head. There was this story that I wasn’t really involved in and had missed out on. My story was being told in a different way that was affected by the internet and all the weird stuff that comes with that.

ECF: Your subjects, which are often people in your life—friends, lovers, fellow artists, family—are all consenting to having their photo taken. But from there, after the photo is taken, that narrative is in your hands. How important is collaboration with your subjects in shaping the narrative of your photograph?

AL: It’s so important. It’s something I yearn for. I want my subjects to feel the same way that I do about the pictures and to see the same importance. It would feel weird to make it into something else, to look sensationalized or make it into something it wasn’t. And it brings new meaning to the work for me to hear the other perspective of the person [to whom] this story belongs.

To claim singular authorship over this thing that involves so many different people … there’s holes in that idea. I care about these people and I want to share the joy of the work. There’s collaborative aspects to situations where I’m holding the camera and pointing at someone else. And then there’s other collaboration where we pass the camera back and forth to each other. It’s been kind of shocking to see my partner’s pictures of me, to see my character implicated in a visual narrative. And to relinquish control, to surrender myself to the process has been super healthy.

I think we all manufacture intimacy all the time. It’s like going on a date—we’re going to a restaurant, we are wearing special outfits, we’re rising to the occasion to make it work.

Part of why I don’t publish a lot is because I don’t want the work to be something that it’s not. I don’t want it to be sensationalized. Like early on in my career when I was working for Ryan McGinley, there was this whole obsession with youth photography. And it’s like, sure, these are pictures of gay relationships, but it’s not capital G gay. It’s relatable to everybody. [My photography] really is about the human condition and love and all of these things that are part of innocence, desire. Like we can talk to anybody about a breakup. It feels the same kind of shitty to everybody. So to be curated in shows that were flashy, toting these narratives I didn’t feel a part of made me not want to publish, or it made me want to retain control over how the pictures are seen and to show them in places where I know they’ll be seen properly. I have trust issues with my audience.

ECF: Much of your work depicts very intimate moments with people who are close to you. Beyond the sex, beyond the nudity, I’m talking about the moments where you’re relaxing, moments where people’s guards are down. What are some challenges that you face in depicting intimacy, and how do you navigate them?

AL: I have a hard time answering that question because my goal when I make pictures isn’t “I’m portraying intimacy and this is something that’s impeding my ability to make something intimate.” I think what’s most rewarding in my process is when that moment happens in front of the camera and it happens in the split second that I press the shutter. Really, the obstacle is time and place. If I could film every single second, that would be awesome. But sometimes it’s the camera itself that impedes the situation. Having to wind the film, to press the shutter. Sometimes there’ll be a moment where there’s something beautiful happening, and getting the camera would just completely change the whole dynamic. It’s those moments that have a kind of unique intimacy that can be impossible to capture.

ECF: Do you think romanticization is an act of rebellion? Or is it an escape? Or somewhere in between?

AL: There’s a romanticization where it’s like smoothing edges and making something into a perfect story. And there is romanticism that is just like finding ways to put all the puzzle pieces together to create meaning out of disparate elements, like the pain, the happy parts, the end, just the everyday. Did I ever show you the Having a Coke with You poem by Frank O’Hara? I think that’s so important to talk about. It’s beautiful and touches on what we’ve been talking about. What resonates with me with that piece of writing, he’s comparing watching his lover eating yogurt to looking at a famous statue at a museum. And it’s like, the statue is considered the most gorgeous thing ever. But having life happen in front of you, with your lover and the yogurt, that is life. Making something that gets as close to that as possible is a goal for my work, while accepting that it is impossible to recreate that. My practice is all in this like fantastical retelling of my life through my romantic lens. It’s something I would pass on to people following in my footsteps. This exists. This is how I did it. This is what happened. This is something that happens.

ECF: This interview, as you know, is for the BURNAWAY Crush theme. This is a little literal, but let’s give the people what they want. Who do you have a crush on right now?

AL: My entire friend group! I have crushes on everybody. A crush happens when you meet someone, and it feels like they’re a door into a whole new world of fantastical things that you’ve never seen before. And it’s also a new lens. Seeing your own life through another person’s lens brings new meaning. My big wave of finding meaning in my life and my existence is through pictures, seeing it somewhere else and in putting the puzzle pieces together. And to have somebody else there to witness things with you. Right now, for me it’s a big group of people who are just fantastic. Together we’re creating meaning out of what it means to be people like us, what it means to be at this particular intersection. Living in Atlanta, pursuing joy, and thinking through all those obstacles and that gets into like queerness and being outside of inherited systems, and also just being in our generation with new technology and everything. It’s a whole new world. We’re navigating all of this together. We have to redefine what it means to be alive. A crush brings the thrill of being alive to the forefront.

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Crush.