Andrea Chung: Between Too Late and Too Early arrives right on time. Curated by Adeze Wilford, this early-career retrospective gathers two decades of Chung’s healing artistic action across eighty-plus works spanning photo-based media on paper, film, and site-specific installation. Connecting over literature, Chung and Wilford found the exhibition title in Saidiya Hartman’s essay “Venus In Two Acts,” which notably terms ‘critical fabulation’ as a method for using historical records to imagine moments lost between memories and museums. Passing down Black feminist traditions, this solo exhibition aligns with Afro-Diasporic authors and ancestors, further evidenced by a reading room full of ghost stories, poetry, nonfiction, speculation, wellness texts, children’s books, and beloved bestsellers. Commit to the recommended reading list or not, Chung’s “Petty Library” (a response to book bans across the US) is full of lessons. If you don’t care for a word from the wise (English, Spanish, Kreyòl-coded labels available) the exhibition visually illustrates a curriculum of care.

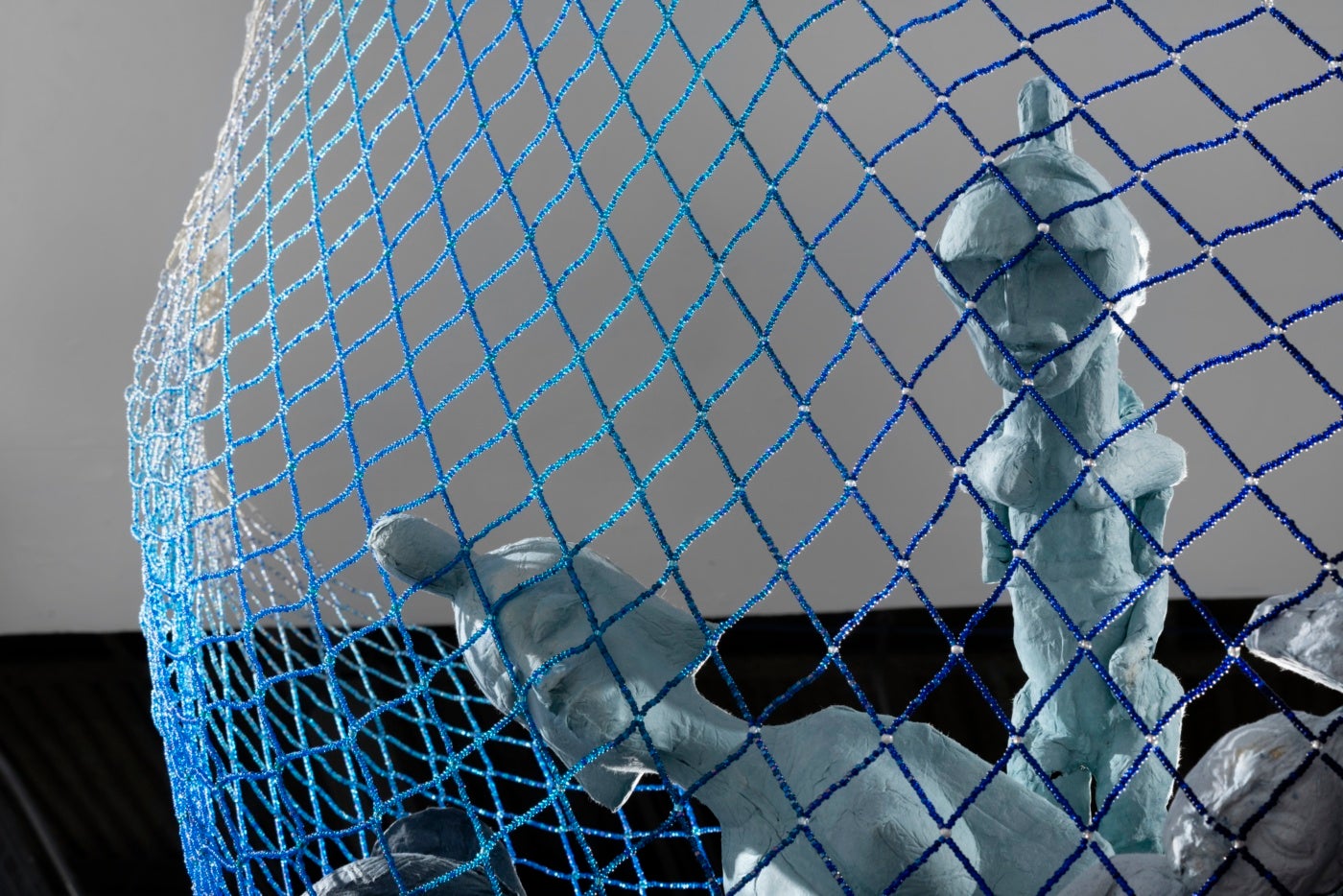

The opening work is a new commission; There is no me, there is I and I, which is you too. You and I intertwined (2024), a beaded net suspended over the gallery’s golden papaya-painted entrance, serving as a reminder to always look up. Caught up in countless clear, black, and cerulean beads are West African fertility figures made of black soap and shea butter. Her softening of the typically carved wooden forms alludes to their tactile treatment as historically handheld companions. Yet out of reach, suspended as if snatched from a dream, their surfaces are dimpled with soft markings like one’s arm after a good sleep. Transformed into a temporal material, the fertility figures resonate a solid aura of prosperity and protection. Gasp-inducing awe at all angles, the net’s woven shadow is haunting, lights overhead casting a double spirit on the white wall. With helping hands, Chung delicately strings together seed beads and pearls into this crisscrossing cradle, subverting the symbol of the fisherman’s net. Across the exhibition, she subverts violent histories to promote a positive perspective for the descendants of trauma. Wilford explains their shared goal is to help visitors “experience comfortability even within complex subject matters.” An enchanting undertaking, the new work exemplifies Chung’s lifelong meditation on cultural material, postcolonial liberation, and Black women’s labor.

Further on in the exhibition, works on paper fill the gallery: Hundreds of cyanotypes sun-stained with lionfish. On either end of the room, watercolor paper ripples. A denim-like patchwork grid tiling the walls makes up two mural-sized motifs of oceanic life, Spectre (2017) and Sea Change (2017). Smaller framed works in between become windows to schools of fast-swimming striped fish prints, paused in an eerie x-ray-esque glow. The milky sharp outline and varied blue-hued backgrounds are signatures of cyanotype: a nineteenth-century photo process in which chemical and sun-activated technology poetically reflects the deep ocean environment in which Chung situates this series.

Diving into the process of reproducing lionfish she discovers online, she works between her bathtub and backyard, capturing the sea life in “cells,” a nod to the medium’s scientific start their cyan apparition an experimental trial each time. Since the 1980s, owing to their aquarium aesthetic allure, lionfish have threatened native snapper and grouper populations and have yet to make it onto dinner plates. The lionfish is Chung’s metaphor for colonizers. They appear open-mouthed; striped quills floating like feathered manes made of venomous spines. Visitors take the perspective of prey, perhaps part of the ancestral treasure catch, encircled by a species deemed ‘devil firefish.’

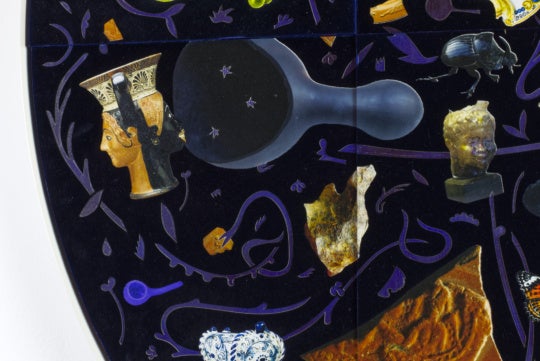

A passageway opens to The Load Is Heavy and My Back Is Tired (2023), three large collage works, which Chung has fixed onto paper handmade from traditional birthing cloth. The gauzy white sheets hold archival, ecological, and ancestral histories and set the visual vocabulary of Chung’s collaged works, which fill the room. Reframing photo histories, Chung pulls ancestral images of women and children from Caribbean, Nigerian, Brazilian, and Afro-American archives across multiple collage series: We Was Girls Together (2021), Sisters of Two Waters (2019), Sula Never Competed: She Simply Helped Others Define Themselves (2021), Vex (2020), and Colostrum (2021), which gather in the gallery. Enveloped in lush and vibrant paper flowers, the families are lifted from droll black and white antebellum stagings of enslavement, pulled away from performing for the colonist’s camera and safeguarded from the violent gain and gaze under which their images were initially taken. The titles reference Chung’s personal library and research-based practice, which educates on the material and medicinal benefits of Black women’s care practices. How does care evolve and circulate under invasion? Chung’s paper protagonists have adapted similar spines of their lionfish predators, protruding from these works as beaded needles. Collaged into a counter-narrative, these stinging sharps protect feminine power figures like the nails of nkisi sculptures, requiring predatory eyes and fingers to keep a safe distance.

Through spaces like this, healing can happen. Chung’s care-filled considerations give the archive agency and honor ancestral labor through meditative art-making and tradition-rich toil.

The Wailing Room (2024) is a site-specific commission, and the penultimate work in the exhibition, that furthers Chung’s engagement with sugar and introduces a startling sound work. To a chorus of laugh-until-you-cry hysterics, dozens of sugar-cast rum bottles are suspended at various heights in the center of the space. There is evidence of those once hanging, with crystalized noose-like lines left in their place. This material transformation began in the kitchen, molten sugar cast and tempered has morphed in the gallery, not by the expected smashing, no shards of broken bottles made weapon, nor Molotov exploding from the inside out. Instead, it’s a curious cocktail, nonetheless sinister, like fainting figures when the spirit leaves the body.

Chung explains the ephemeral nature and “life span” of cane sugar, a medium she also molds into rum bottles and bibles and presents as confectionary crystals mineralizing over cyanotypes within the wider exhibition. In each sugar installation, the material changes forms, falls into the frame, drips off the pedestal, slowly spills, emits a scent, and appears different at each encounter. Invisibly, an artist-induced labor activates it. Bottles slump to the ground like childless mothers fall from their feet. This ephemeral installation embodies the intoxicating haunt of Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987). Their painful apologies for infanticide are left private, Chung placed letters in the bottles, correspondence between mother and child left illegible as scrolls in sugar syrup. Their last words are silenced by a sinister wail and laughs of jubilee.

The final gallery focuses on the Black Atlantic, Paul Gilroy’s concept posited here through Drexciya, an afro-futurist underwater world (conceptualized by Detroit house musicians James Stinson and Gerald Donald), and a key reference in much of Chung’s practice. Self-liberated, Black kin in Drexciya do not need air to breathe; they thrive in the depths. If they put an iron circle around your neck, I will bite it away (2022) animates the loss and longing of the slave ship icon. A Victorian parlor room sits stiffly in the corner like its owners once did. Chung tells me she’d never sell images of her kin. The installation works to rival ownership mentalities, an ironic and intentional addition considering the exhibition’s run during market-driven Miami Art Week.

Through spaces like this, healing can happen. Chung’s care-filled considerations give the archive agency and honor ancestral labor through meditative art-making and tradition-rich toil. It is not only the past that needs to be resolved; her practice calms anxieties and aggressions that haunt ecological, institutional, personal, and professional environments daily. During the reception, the artist wears the word Kingston around her neck: a nod to her Jamaican Trini-Chinese heritage, but the nameplate truly honors her kindred.