My artist practice is a journey directed by fragments of memory. These memories are fragile, inconsistent in their material tangibility but equal in their spiritual substance. Some memories I can hold in my hands, sense the vitality that pulsed through their makers and now the objects; some are carried through voice, an ardent reminder “this is your legacy”; some are dreams whether borrowed, self-constructed, or collectively imagined, visions of what could/should/would have been. Nearly a lifetime of slides from Pop Pop, copious newspaper clippings from the Bucks County Courier Times, that phone call, copies of journal entries, patiently rendered family trees, coveted swamp water, etc.—this collection is a container. Like memory, some containers are full of holes, some are seemingly indestructible, some are transparent, while some are obscurely opaque, and others so shiny that the light they reflect is blinding. This collection has created a map, not one with an expected destination, a singular starting point, or even a key—only an invitation. This map directs me South to the ports of my ancestors: Garysburg, North Carolina; Lynchburg, Virginia; Gee’s Bend, Alabama; Charlotte Amelie, St. Thomas. The so-called origin points of my ancestors have become the harbors of my practice. The places on the map from which I depart and to which I return. Borrowing from Audre Lorde, this chapter of my practice is its own kind of biomythography—a mixed bag of history, (ancestral) biography, and myth.[1]

The Great Dismal Swamp, a large expanse from northern North Carolina to southern Virginia, is a paternal port that invited me to explore the revolutionary practice of marronage.[2] To know more, I followed the long stretch of this practice and landed in one of the places where, unlike in the United States, for many it maintains a “national memory”—Bahia, Brazil.[3] Separated by more than four thousand miles, yet inextricably linked by a shared history of marronage Bahia became a cherished point on the map of my practice. However, shared does not equate to same; as my Dad would say, “two sisters’ children.” This historical Brazilian–American familiarity broadens the possibilities of my speculative, ancestral “rememory” and rejects a diasporic homogenizing.[4] In 2018, I attended the International School of Transnational Decolonial Black Feminism hosted in Cachoeira, Bahia, on the heels of graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in Providence. I was rejected by a RISD graduate studies grant to fund my attendance to the school and associated travels. My graduate cohort generously interjected sharing funding from their successful graduate study grant applications helping me build a bridge from the Swamp to Cachoeira – I was completely stunned and so beautifully assured.

Images taken by the artist during the Festival of Yemanjá, February 2023, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil.Photograph by and courtesy of the artist.

In Cachoeira, I met Dona Dalva[5] and was bathed in her samba; I listened intently as scholar and advocate Kimberlé Crenshaw[6] lectured; I was cleansed with popcorn by the proprietor of a local pousada who I had met in the square and by Quilombo Konge’s ialorixá[7]; I was joined by my mother’s brother; and I stood in awe of the maternal society of Irmandade da Boa Morte during the annual Festa de Boa Morte.[8] Since that trip in 2018, my practice has evolved from an effort to illustrate a vision of the Great Dismal Swamp and the diasporic ties it holds to an active practice of ancestor worship shaped by the wake of ancestral ports.[9] What now feels so obvious, but which was at one time a tectonic shift, is an understanding that orality, ritual, and craft are interdependent Diasporic practices of freedom and my inheritance. This shift has decidedly centered my work in a space of joy, reverence and connection.[10]

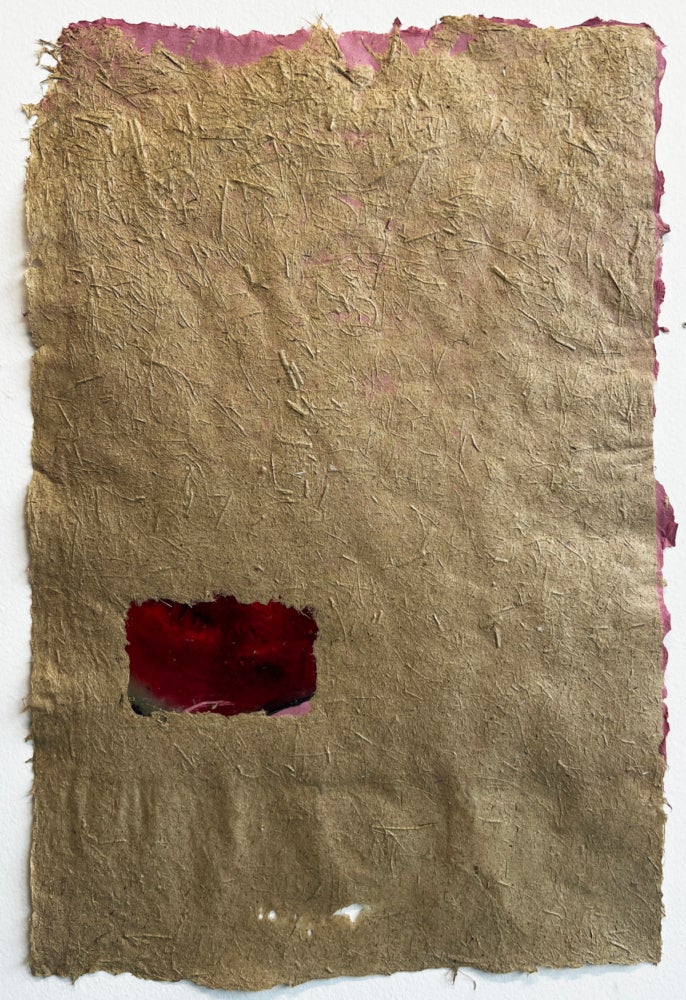

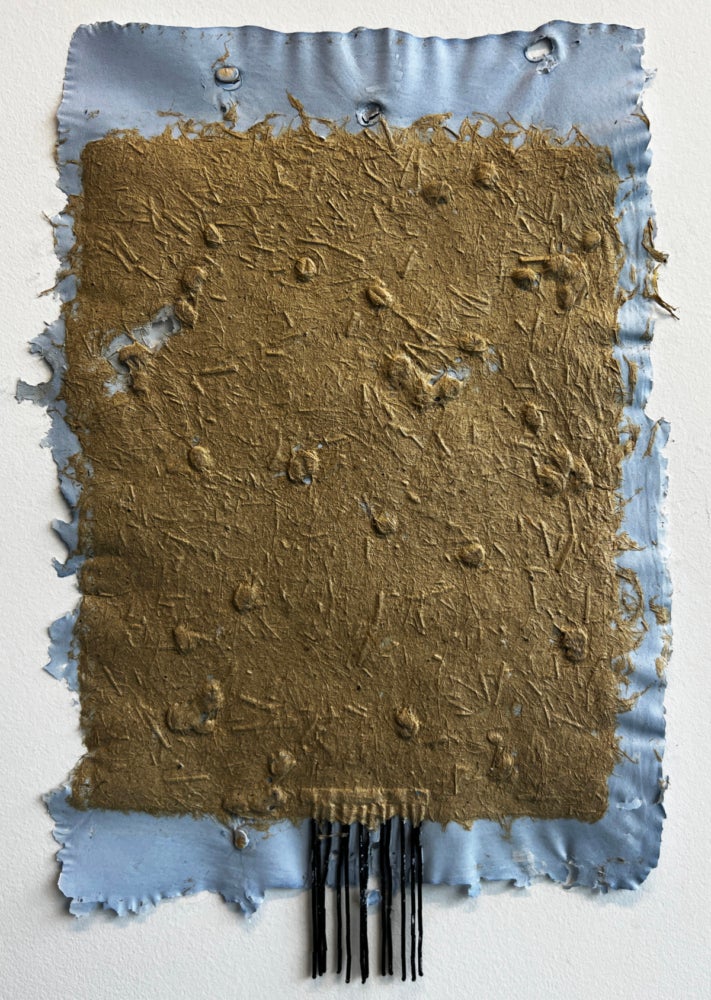

As I come to know my artistic practice as ancestor worship, I see how it is crafted by intuition, embodied knowledge, and a patient learning of the extensive, intersecting, active and historical traditions throughout the Africana Diaspora. On constant rotation include The Yoruba Religious Handbook by Baba Ifa Karade (1991) and Sacred Possessions, a 1997 collection of essays edited by Margarite Fernández Olmos and Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert; I am currently wading through Toni Cade Bambara’s The Salt Eaters (1980). In these texts, conversations with peers, the confines of my journal, the privacy of my studio, or the collectivity of the classroom, water rises to the surface. It reveals itself as a transformational tool for rebirth, an ancestral invitation, a generational sense memory, and as the unchanging constant in hand papermaking.

I returned to Salvador in Bahia, Brazil, in February 2023., This time supported by The SMFA at Tufts Travelling Fellowship to attend the Festival of Yemanjá, honoring the orixa who is the mother of the sea and all living things. Traveling with my partner and my mother’s brother, we joined the thousands of others who had come to make their offering to Yemanjá. As the sun set, processions of people carrying flowers on their heads, in their hands, or being pulled from behind journeyed through the Rio Vermelho neighborhood alongside a convergence zone of music to the shoreline abutting Casa de Yemanjá. The air was full with the smell of acarajé, a sacred dish that uses staple ingredients like black eyed peas, peanuts, and okra—foods that are also staples in the material vocabulary of my artist practice, making synchronicities tangible. We found ourselves invited into a procession, an invitation transmuted only through knowing eye contact, warm smiles, and outreached hands. Once we arrived at the beach, Praia Rio Vermelho was harboring others who were enacting their own rituals and somehow the robust sounds of celebration from the street above became quieter. The offering of generous white flowers was set on the sand, and we surrounded it in a candle-lit circle; it was then ushered into the sea by boat and from there delivered to Yemanjá. After, heartfelt obrigado’s were exchanged and we sat on the shore processing our deep appreciation for being so tenderly included in such an intimate collective moment. As my partner and I reflected, we saw countless other groups, pairs, and individuals arriving at the beach, offerings in hand, and journeying with one of many sailors waiting in their boats. They disappeared together into the dark, beyond the stretch of light coming from the festa behind us and returned soon after. The sun came and offerings continued; ready and called, just the two of us boarded a boat and conveyed our offering. On the water, the sea was like something I had never encountered before, roses, roses, roses. For a moment as the boat stilled, only rocking from the rhythm of the water, it felt like we were cocooned by a bath of prayers, intentions, and thanks.

Yemanjá, Oshun and Mami Wata are all present in Great Dismal Swamp and in my papermaking vat. The vat is the genesis of forming paper, it is where plant fibers mix with water to create something entirely new and entirely familiar. It is a water body in which the synchronicities of ancestrality can congregate. These moments of fellowship are fostered by paper’s source fibers, which call back to the harbors of my practice: North Carolina peanuts, Georgia kudzu, Georgia Spanish moss, and Alabama river cane. Black eyed peas, altar cloths, cowries, and sequined trimmings all contain material histories that live in my work alongside the multivalent meanings that are newly ascribed.

I am writing now as I prepare for Memory Worker, my upcoming solo show at Lyndon House Arts Center in Athens, Georgia that is opening November 18, 2023. There are so many routes to travel in my practice, and I reflect and look forward from a place of profound gratitude. To create work within an abundant and active lineage of memory workers of the diaspora is like a laying on of hands, covered, protected, blessed.

Photograph by and courtesy of the artist.

Photograph by and courtesy of the artist.

[1] For more on biomythography, see Audre Lorde, Zami, a New Spelling of My Name (Trumansburg, N.Y.: Crossing Press, 1982).

[2] According to Modern Marronage, a research project affiliated with the University of Bristol, “Dictionary definitions of ‘marronage’ describe it as the process of extricating oneself from slavery, and connect it to the histories of enslaved people who ran away and formed ‘maroon’ or ‘quilombo’ communities in the Americas. However, as political theorist Neil Roberts has argued, ‘marronage’ can also be more broadly understood as action from slavery and toward freedom, and we approach marronage as a concept that can encompass many different ways in which enslaved people sought to practice freedom.” See the website Modern Marronage: The Pursuit and Practice of Freedom in the Contemporary World, University of Bristol, https://mmppf.wordpress.com.

[3] According to Adam Bledsoe, “More than simply a reaction to slavery and non-being, marronage was perhaps one of the most creative and emergent methods of life-building found in the modern world. Maroon communities, today, occupy national memories in various manners. . . . The history of maroon communities (known as quilombos) were drawn on by the Black Movement in Brazil in the 1970s and 1980s to make claims for land redistribution in wake of the fall of Brazil’s Military Dictatorship, the spatial figure of the maroon community is largely absent from the national memory and imagination of the United States.” See Adam Bledsoe, “Marronage as a Past and Present Geography in the Americas,” 57, no. 1, “Black Geographies in and of the United States South” (Spring 2017): 30.

[4] “Rememory” here refers to the act of recalling the forgotten. See Toni Morrison, Beloved (New York: Vintage Classics, 2007).

[5] “Dona Dalva, as she is known, more than 60 years ago founded and maintains one of the most traditional Samba de Roda groups in the Bahian Recôncavo, Samba de Roda Suerdick. At 91 years old, Dona Dalva is considered a living legend and a reference of popular cultural identity.” http://www.cultura.ba.gov.br/2019/07/16721/Documentario-Dona-Dalva-Uma-Doutora-do-Samba-e-exibido-no-CCPI.html. Originally published in Portuguese. Translated by Google.

[6] “Kimberlé W. Crenshaw is a pioneering scholar and writer on civil rights, critical race theory, Black feminist legal theory, and race, racism and the law. […]Crenshaw’s work has been foundational in critical race theory and in “intersectionality,” a term she coined to describe the double bind of simultaneous racial and gender prejudice.” https://www.law.columbia.edu/faculty/kimberle-w-crenshaw#:~:text=Kimberl%C3%A9%20W.,University%20of%20California%2C%20Los%20Angeles.

[7] A priestess in the Afro syncretic religion of Candomblé.

[8] “The Irmandade da Boa Morte is an Afro-Catholic religious sisterhood that, in its origin and for a long time, was responsible for the manumission of countless enslaved people. The group was formed exclusively by Black women over age thirty-five in the 19th century in Salvador, near Barroquinha. However, it was in Cachoeira that they put down their roots.Cultural producer Valmir Pereira, who has worked in the Irmandade for twenty-seven years has said, “History is intertwined with the slave trade from the African Coast to the sugarcane Recôncavo of Bahia. The first signs are from 1810, in Salvador, from slaves coming from Africa, but the group ends up extinct in the capital, due to persecution. Therefore, some sisters went to Cachoeira, in 1820. Thus, the Irmandade em Cachoeira was created.” The sisters affirm that their devotion to Nossa Senhora da Boa Morte (Our Lady of Good Death) was linked to their desire for the end of slavery and for a dignified death. Sister Zelita Sampaio explained, “Blacks were not treated well, so they always asked Our Lady for a good death by her side, because we didn’t even have the right to die with dignity.” See Mario Jorbe, “Festa da Irmandade da Boa Morte começa neste sábado (13) em Cachoeira, Recôncavo Baiano,” Nosso Propósito, August 12, 2022, https://noticiapreta.com.br/boa-morte/. Translation Google

[9] See Christina Elizabeth Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press 2016).

[10] I cite Bettina Judd here: “The dimensions of joy outlined here are: (1) the complexity of human experience (i.e., “the whole of life”), (2) acknowledgment of the difficult, and (3) conscious, habitual, and deliberate choice. This tripart and cooperant atheology embraces joy in its complexity because life is complex. It acknowledges the feeling as hard-edged, multifaceted, exuberant, and inclusive of the difficult.” See Bettina Judd, “Lucille Clifton’s Atheology of Joy!,” in Feelin: Creative Practice, Pleasure, and Black Feminist Thought (Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 2023), 69–92.