The poem “An American Sunrise,” by Joy Harjo (Muscogee) begins, “We were running out of breath, as we ran out to meet ourselves” and ends, “We are still America. We know the rumors of our demise. We spit them out. They die soon.”

The exhibition American Sunrise: Indigenous Art at Crystal Bridges opens with Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s (Salish and Kootenai) large-scale painting Green Flag (1995), in which swaths of red acrylic paint are layered over a ground of text, including lines from diverse sources like Pablo Neruda’s poetry: “Give me silence, water, hope / Give me struggle, iron, volcanos,” snippets from newspapers, with phrases such as “meeting tomorrow’s challenges today,” and President Ronald Reagan’s response to redwood conservation efforts: “A tree is a tree—how many more do you need to look at?”

Referencing Jasper John’s Flag painting (1954-55) created during America’s McCarthy era in the mid-twentieth century, Green Flag alludes to the country’s continued legacy of environmental and political degradation, as well the complexity and contradiction that can occur in the space between the symbol and the real—as in the case of a star-spangled banner representing the concept of majestic freedom and the legacy of genocide such a symbol elides.

American Sunrise presents works by over thirty artists from the museum’s permanent collection highlighting themes of intergenerational knowledge, oral history, kinship, place, and Indigenous Futurism. Jordan Poorman Cocker (Kiowa), curator of Indigenous art and NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) officer at Crystal Bridges commented that she “wanted this exhibition to showcase a more holistic and truthful context for Indigenous art within the United States…with intentional multi-vocality” as well as “to celebrate the historical and ongoing relationships Indigenous peoples carry between the land; intergenerational artistic expressions; and the resilience of kinship between Indigenous artists and place.”1

Concerning the site of the exhibition in Northwest Arkansas, sculptor Jane Osti (Cherokee Nation) noted the region “was the final part of the Trail of Tears before reaching Indian Territory (now known as Oklahoma).” Osti’s hand-dug clay vessel Journey Through Arkansas (2024) features a form inspired by historic pottery found in the state with traditional stamped motifs to mark the passage of the Cherokee through Arkansas during the 1830s. Another of Osti’s vessels, A Sacred Fire (2024), is exhibited and references the embers of a ceremonial fire carried throughout the journey from ancestral homelands to the territory of Oklahoma.

Andrea Carlson’s (Grand Portage Ojibwe, European Descent) four-panel drawing Final Ikwe (2024) is part of a series that utilizes imagery of the cannibal, known as the Wendigo in Anishinaabe stories, as a symbol for colonization’s tactics of cultural erasure and appropriation. A sharply drawn Winged Victory of Samothrace (190 BC) with a cut-up sign demarcating a historical “Indian community” sit atop colliding waves in the collage-like composition, where metaphors for the hierarchies of history, whose stories are revered and preserved, and whose are suppressed, meet each other in a turbulent sea.

A feathery pastel landscape by Pop Chalee (Merina Lujan; Taos Pueblo) titled Enchanted Forest (ca. 1950) contains gossamer brushwork and delicately-rendered fauna beneath a canopy of undulating willow and cedar branches. An example of the “flat style” associated with the San Ildefonso artists, the natural imagery painted in a tapestry-like composition reflects the artist’s childhood summers spent exploring the beauty of the New Mexico landscape.

Edward C. Robison III and image courtesy of the artist and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

An example of the Kiowa style of painting, Steven Mopope’s (Kiowa) Untitled (1931) striking figurative work in gouache depicts an archer peering skyward. Razor-sharp details, without shadow or shading, give the figure the appearance of being nearly incised into paper. Mopope was among the painters of the Kiowa Five, which later became the Kiowa Six, known for extending the tradition of record-keeping and heraldic imagery of the Indigenous Plains tribe with distinct, flattened compositions connected to Kiowa oral history. The work of the Kiowa Six was instrumental in challenging the stereotypes deployed in depictions of Native Americans and was exhibited internationally at sites such as the Venice Biennale in the 1930s.

The Pueblo Revolt 1680 / 2180 (2016), a clay vessel with Pop-esque acrylic figures by Virgil Ortiz (Cochiti Pueblo), draws on the nature of clay as a material connector to the deep past and references the 1680 revolt of the Pueblo people against Spanish colonizers—which the exhibition notes has been largely excluded from dominant historical narratives—as well as a potential dystopian twenty-second century.

Connecting craft and social practice, Kelly Church’s (Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Tribe of Pottawatomi / Ottawa) large-scale Black Ash, wood, and copper basket, Sustaining Traditions Into the Future (2024), is intricately woven out of a species of tree the artist noted at an exhibition panel discussion is at risk. Church, who is concerned with the colossal amount of Black Ash trees being lost in Michigan to the Emerald Ash Borer, integrates replanting and education about tree conservation methods into her artistic practice.

Teri Greeve’s (Kiowa) elaborately beaded box Gyok-Goo, The Story of my People (2000) is constructed of deer hide and birch wood as a “pictorial history” of her Kiowa ancestry crafted for her son in a form that was inspired by parfleches—traditional painted rawhide containers. Greeves stated at the panel discussion that while the artistic contributions of Native American women have not been properly attributed in most museum collections, it is important to acknowledge that: “Traditional Native American art is actually made by women. Women hold the knowledge and the ways of producing these things…textiles, ceramics, weaving, all of it.”

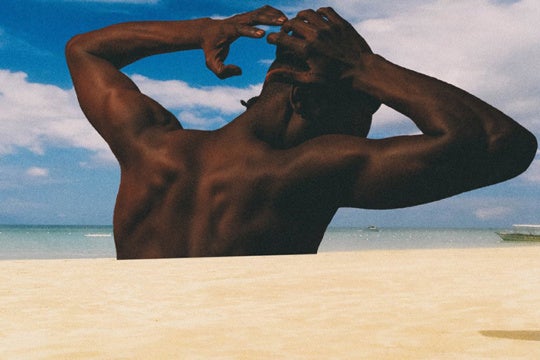

Martine Gutierrez’s photo Queer Rage, Imagine Life-Size, and I’m Tyra p66-67 (2018, printed 2020) presents the artist seated in a lush landscape adorned in brightly-patterned textiles. Referencing pop culture’s tendency to present Native American culture as monolithic, the photograph mimics the fashion industry’s appropriation of Indigenous culture without context or specificity.

“An American Sunrise” opens with an image that alludes to the nonlinearity of history: “We were running out of breath, as we ran out to meet ourselves. We were surfacing the edge of our ancestors’ fights…” Poorman Cocker, the exhibition’s curator, has noted how “Harjo’s poetry opens a dialogue with American history through the lens of Indigenous Nations’ relationships to the land through past, present, and future timelines.”2

In the aftermath of Trump’s second inauguration, the lines of Poet Laureate Joy Harjo’s “An American Sunrise” resonate deeply because misidentification and desacralization of Indigenous lands has never ended. On day one of Trump’s second term, an executive order was issued renaming the tallest mountain in North America—known as Denali to the Indigenous Koyukon Athabascans of Alaska—to “Mount McKinley” (in honor of a man who’d never set foot in the state). Additionally, there remains an unresolved case between the Lakota Nation and the US government, who reneged on a treaty concerning the sacred Black Hills and consequently pummeled them into the symbol of Mount Rushmore.

“We are still America. We know the rumors of our demise. We spit them out. They die soon.”

The poem and the exhibition American Sunrise both point to the continual resurfacing of history’s injustices that have been repressed rather than integrated, addressed, and repaired. America, and its concept of democracy, still rests precariously on oversimplified images and narratives of Manifest Destiny. Meanwhile, the history of genocide and displacement of Native Americans, the systemic suppression of their cultural expression, and the untenable extraction of resources from their ancestral lands, forming the unstable foundation of America, is once again being elided within the narrative of the new administration. This whitewashed, mythic image of America buckles under the weight of its original injustices. The artists exhibited within American Sunrise offer multivalent images of this troubled history, as well as the possibility for deeper and more sustainable forms of knowledge, lifeways, and relationships to the land and each other.

[1] Interview with the author, February 18, 2025.

[2] Interview with the author, February 18, 2025.