If you were to imagine a humanoid embodiment of the ancient wisdom held in the whispers that line the Bayou’s basin, the inexorable nature of an arrow on an upward trajectory, and the sheer substance of sun itself, your mind’s eye would likely conjure the spirit of Amarie Cemone Gipson. The Houston-based curator, writer, DJ, and archivist formerly held positions at The Art Institute of Chicago, the Studio Museum in Harlem, and Houstonia Magazine. Gipson most recently became the 2023 Freedmen’s Town Research Fellow at Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston. Lately, she has been focusing on The Reading Room, Houston’s first Black art reference library, which Gipson founded earlier this year.

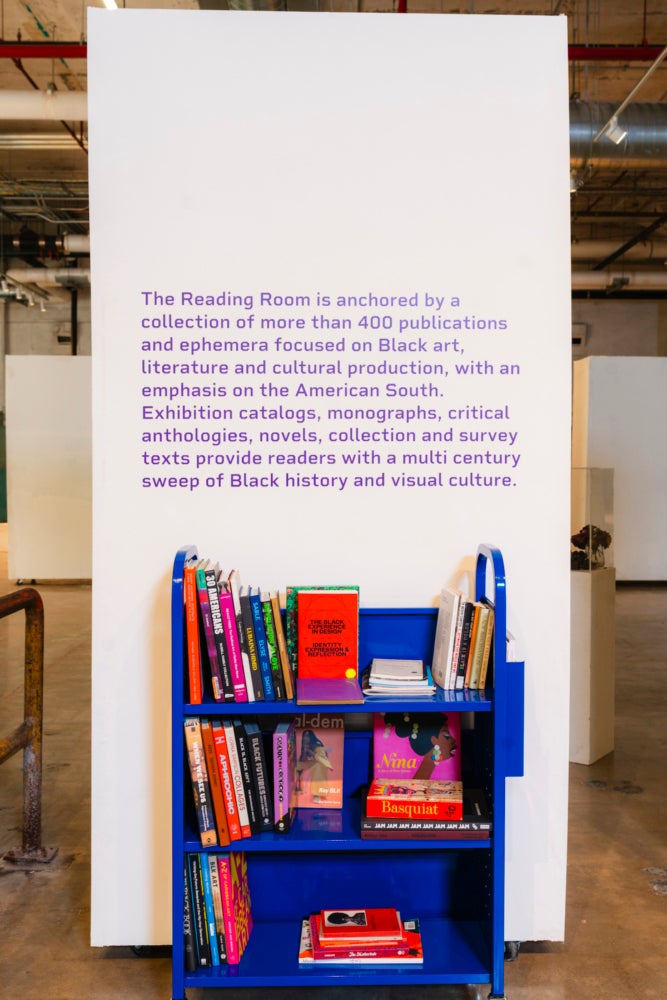

In addition to serving as a repository for information about Black artists from across the globe, The Reading Room breathes life into its contents by hosting panel discussions, film screenings, and informal gatherings, wherein knowledge is not only preserved, but exchanged and created as well. As such, Gipson’s latest venture can be considered a kind of social sculpture, insofar as it creates avenues for casual intellectual exchange and collective knowledge transmission unmediated by the myriad of strictures often enforced by traditional sites of epistemological import like libraries and museums.

The maverick’s work, regardless of the medium through which it is actualized, exudes the core ethos of fellow writer Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s utterance of Black feminism as a “rigorous love practice.” The Reading Room serves as an index of Gipson’s keen capacity to enact Gumbs’s articulation in at least three directions. Towards her community and collaborators, towards those who call her beloved city home, and back towards her own self as well. Below, you will find a conversation, conducted on the heels of The Reading Room’s inaugural pop-up, about the project’s origin story, Gipson’s anti-institutional stance, chopping and screwing as an allegory for multi-modal creative practice, and the importance of site specificity as a means of imbuing work with a sense of sincere responsibility.

Camille Bacon: Can you please share with us the origin story of The Reading Room?

Amarie Gipson: I got back to Houston from New York in January 2021, and I said I’m just gonna have to do it myself. I was looking for a place where I could be surrounded by books but that was less rigid than a public library. I wanted a place where I didn’t have to walk through a formal institution to see the books, where I didn’t have to have a library card. I wanted a place where I could find textual materials in a setting where I can also look over and say hi to one of my friends. That doesn’t really exist, especially here in Houston.

The imperative goes back to this idea of my sovereign sensibility. If the place doesn’t exist, if you can’t find it, you have to build it, like Toni Morrison said. I’ve been in the collecting institutions, and non-collecting institutions. I’ve been in the university setting. None of it was satisfying in the way I knew I needed. So, again, this just meant that I literally had to make it. It dawned on me that I’ve been collecting art books since I was in twelfth grade and so I decided I was gonna create that space to share them with people. And that’s how The Reading Room came to be.

I have to name Asmaa Walton and the Black Art Library as a predecessor. Her journey with that project was a major resource. I was so inspired by the way it seemed like she kind of just stumbled into doing the thing, because it showed me that I could do this, too. It also reminded me that libraries have also always been a part of my life.

CB: Tell me more about the role libraries have played in your development.

AG: [As a child], my grandpa would drop me off at the neighborhood library and sit in the parking lot and just have time for himself while he waited for me to come out. Meanwhile, I would be inside, finding all the things that I could possibly find, running around, looking at the stacks. As I got older, I graduated to logging on to get computer access but, early on, I was sitting in the kids section and asking the librarian questions. So that would be my thing on the weekends and after school, you know, if I wasn’t hanging out with my cousins or we weren’t in church or whatever. That time with myself outside of home spent in communion with the books gave me agency over my own mind and ideas, and I wish to extend that opportunity for other people through The Reading Room’s presence in Houston.

Also, the reading room, structurally speaking, has always been the most exciting part of a library to me. The display of books, the variety of books, and the fact that this is usually where people are gathered. The reading room is also where the books come alive. It’s cool if they’re on the stacks, but it’s in the reading room where the sociality and intellectual exchange happens.

The Reading Room I created is a kind of anti-institution for all of these reasons. It has the potential or, I think, the depth and intention to be an institution but, really, to become a new type of institution. I think about what it means for the people who make up an institution to be aligned and working towards something that’s collectively meaningful, being accountable for it every step of the way and finding ways to meet people where they are versus trying to refine them.

CB: I’d love to spend some time thinking together about the stakes of the language of anti-institutionality to describe what you’ve built. I wonder if this has something to do with why you’ve called it a “Reading Room” instead of a “library”?

Removing the language of “library” altogether feels like an important proposition because they are indeed traditional institutions in the sense that they centralize resources and dictate the terms on which people can engage them. For example, you normally need a library card, which you mentioned, and need to be quiet in the space, which has a whole set of implications where Black being, in particular, is concerned. The Reading Room is certainly centralizing resources but does not depend on a kind of policing or undue scrutiny around the particular modes through which people wish to gather, express, and engage the books. Visitors to The Reading Room aren’t going to be punished for not following the unspoken conventions of the thing because there are no conventions and I love that.

It seems like you’re building, not an institution in the normative sense, but an environment for people to convene in the name of collective thinking, feeling, learning, and expansion. Moreover, you’re creating a site for people to gather and use the resources to grapple together in earnest around their curiosities. So, there’s also potential for a new model of collaborative knowledge production here. The care you’ve applied is not the function of normative institutions, but is, without question, what The Reading Room is doing and will continue to do.

AG: Exactly. There are no behavioral expectations. If you’re curious, if you’re bored on the weekend, whatever you want to do, you’re met exactly where you’re at when you walk in.

I don’t think I necessarily have to have a library science background to make things accessible, right? So I’m also rebuking the credentialism that traditional institutions fuel their misguided sense of prestige from. I’m using the skills that I picked up along the way on how to connect with people, how to give a generative reference point to something, and how to connect the dots around broader ideas and movements.

Thinking explicitly about this idea of anti-institution, I didn’t want to call it a library because of the pressure and the specific associations to normative power that word holds. I am not interested in amassing objects just for the sake of it. The collection was amassing itself subconsciously, where I looked up one day and realized I had all these things, so I might as well share them.

CB: Your project feels like it’s also in lineage with the ethos through which Arthur Schomberg gathered what is now the contents of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a New York Public Library branch. His acquisition and consolidation of ephemera stemmed from an existential frustration whose seed lies in an experience in grade school, wherein his teachers claimed that Afro-descendent people were bereft of history and culture. He dedicated his life to amassing resources, artifacts, documents and other objects to disprove their clause and to provide access to an abundance of materials that served as evidence against his teacher’s faulty claims.

AG: Yes. Before I even decided to start buying books with The Reading Room in mind, I was really going off of whatever I picked up in museum gift shops, books that were mailed to me, or texts I was using as reference for a certain project. Or, even just the ones I thought were really beautiful that I wanted to have and live with.

Also this space, The Reading Room, is going to be so important because there’s not enough places in the world where we can learn about the South. That’s the focus, it’s a part of the mission: To ensure that there’s enough evidence, just like Arthur Schomburg intended. That evidence has existed for decades, but it’s vital that it’s in a place where you can access it, and people can come to know for themselves. When I did the first pop-up in March, I got to see firsthand how much it meant to people to walk into a space where they could learn about so many things at once. Somebody said to me: “I didn’t even know this many books existed on Black art.” And I mean, how else would anyone know that? So, access is something that is so important to me. Yes, access to opportunity, sure, but access to knowledge more than anything. Access is probably the one thing that stands in the way of somebody reaching their full potential and The Reading Room hopes to be part of a larger lineage that drastically changes that.

CB: Can you give us a fuller sense of the timeline for The Reading Room and how things developed?

AG: The timeline started as soon as I touched down back in Houston in January of 2021, as I mentioned before. I hit the ground running with one question: What is it going to take for me to have a space that is free for people to come in with no expectation to buy things? What do I have already that makes that possible? Well, books!

By the end of 2021, I bought the first book: Another copy of Duro Olowu’s catalog, Seeing Chicago, and that was the first official acquisition for The Reading Room. By December 2021, I was pretty stressed out with my work at Houstonia Magazine, so I was looking for a long-term exit plan. I was several months into having founded Physical Therapy. I knew that I didn’t want to work at that magazine for a long time, and I also knew I didn’t want to be a full-time DJ. So, I needed to start putting my effort towards the thing that I was going to do that’s completely my own and began constructing The Reading Room’s mission statement. I started to pull together a sort of game plan for the launch, while giving myself some grace, because at that time, I didn’t have a lot of free time, I didn’t have a lot of mental space, I didn’t have a lot of room to imagine in the way that I really needed to.

I got through a really, really transformative 2022 where DJing and nightlife and that area of sociality became the primary way that I was sharing myself with the world. I had been telling people all throughout 2022 “I’m working on this thing and it’s called The Reading Room.” I would say it over and over and over and over and over again until I finally got the opportunity to make it a thing, at which point, I had been speaking it into existence for almost two years.

I got laid off from the magazine in November 2022 but had been saving for months and came into a small fortune from a collaboration with Spotify through Physical Therapy. Then the momentum really picked up. I found the signature typeface, started cataloging the collection, built the spreadsheet, bought a really nice scanner, started thinking about the design for the website, and contacted a web developer to help me out. And then it was time to shake: Two years of thinking about this thing and the project launched and came together in a span of two months. I dropped the website in February of this year and had the pop-in in March.

CB: Another thing I deeply admire about your work is how you’ve been able to call together so many different disciplines: You’re a writer, a curator, a DJ, an archivist, a librarian and more. I’d love to discuss how your practices feed one another and how your interdisciplinary mode of working informed your process of selecting books for The Reading Room. It feels like you’re enacting a sort of sampling, mixing, chopping, and screwing in ways that exceed the musical associations of that language.

AG: In thinking about this idea of chopping and screwing, that’s a practice and a method that’s so characteristically Houston. It’s so characteristically Southern and I take a lot of pride in being a Black Texan. I’ve worked in museums, media companies, all across the board and being able to take certain practices from each of those institutions has been really important. It is indeed a sort of sampling, it is indeed a sort of a mixing. Through The Reading Room, I’ve taken on the role of collection manager, archivist, librarian, fundraiser, and developer too.

I love those moments where I’m actively conscious of how the practices feed each other, too. Then, I can connect my work in all facets to other things, like you said. I love that with both DJing and my love for art history. I can travel to a certain decade. For instance, I can look at a painting that I love and say what would they have listened to in the studio? What came out maybe two or three years before the painting that I can go and try to find?

As far as book selection for The Reading Room goes, it’s similar to the way I’ve really held close this bank of 500 songs that have come to define my sound as a DJ. I think about the texts in The Reading Room’s collection the same way. Every time I play a set, or whenever I’m approaching another party or a gig, I’m thinking about the things that people know, but what are the things that I want them to know? What are the songs that you didn’t know you needed when you showed up? Same process, same method for the collection.

On a practical level, I got in touch with Asmaa and looked at her collection. I started to pull things that I’m drawn to and texts that speak to foundational people or moments in history, and then started to buy new texts from there in a way that was propelled by a sensitivity to my own blindspots. For example, I started to collect more texts about Caribbean art and what Black artists are up to in the UK so we can have holdings that speak to the global diaspora.

CB: Let’s talk about the site for a second. There’s a clear spatial and historical link between Houston, being the first sovereign community of emancipated Black people in this nation, and this “sovereign sensibility” you embody and speak of. I wonder, then, what does it mean for you to be in Houston, from Houston, offering this gift of your presence on so many different fronts to your city?

AG: My response to that is: Where else? Where else would this make the type of impact that I know it will make here? I would not have been able to execute, conceive, or be trusted with something so special if I wasn’t from here. When I moved back, a world of possibility that I could not have ever imagined opened up. I would not be able to have the life that I have, or do the things that I’m doing, or make the impact that I’m making if I was anywhere other than right here. It wouldn’t mean as much. It wouldn’t feel as real. It wouldn’t feel as necessary. Houston is one of the greatest cities in the world. There’s something here about tenacity, work ethic, and the spirit that it takes to move through things like disappointment and grief and heartbreak but also joy and triumph. We do all of that here.

I think there’s also this centuries-long debate around the South as a place of criticality and whether or not it actually has the depth to be that or not. When I think about the South, I’m thinking about the bottom of the map, this place where I’m literally at the bottom of the American map, the U.S. map, looking up and around and all of these other things that are happening. That’s my positionality, geographically and otherwise. Theoretically, and otherwise, I’m literally here, looking up at everything around and it all comes back down to here. If you want to understand American history, you have to know the South. You’ve got to know the Great Migration. You’ve got to know that Houston is a port city. You’ve got to heed the depth of the water of the Bayou.

Just think about a holiday like Juneteenth. I am forty-five minutes away from where that happened right now. Fifty-five with traffic. Black ingenuity, creativity and spirituality – these life-giving forces – they live in the air here. It’s in the water here. You feel it every time you leave the house. It comes up and it’s in our spirits. It’s in our character. I intend for The Reading Room to be yet another reason to spend time in this sanctified place.