Energy continuously changes direction as it flows in alternating current circuits. There are factors that dictate these back-and-forth waves, but change is constant and necessary to complete the circuit. Artist residencies operate in much the same way—they rely on constant exchanges of energy and time, and many artists experience peaks, valleys, and turning points in their careers as a result. With time-based, site-specific periods of intense focus on one’s practice, residencies are usually discussed for their capacity to “not only accelerate the encounter between cultures but also demonstrate the aptitude of artistic and cultural production for the construction of bridges between people and places.”[1] While this is true, the reality of site-specificity can be complicated—both for the artist entering an unfamiliar environment, and for those who call it home.

I first learned about artist residencies during my undergraduate programme at Lancaster University, UK. At the time, the concept felt foreign and unattainable; the idea that a dedicated space, anywhere in the world, would be made available for the sole purpose of fostering creativity felt surreal at this nascent stage of my career. It was on returning home to Barbados and becoming truly acquainted with the contemporary art scene that I realised there were in fact residency programmes beginning to be developed locally, existing opportunities regionally, and that many Caribbean artists were already attending internationally.

With this exciting discovery of mobility and exchange, residencies became more tangible. In the context of the Caribbean, it is impossible to discuss mobility without acknowledging issues around access, belonging, and claims to space, particularly through the lens of colonial histories and modern tourism economies. Looking at artists’ motives for choosing residency destinations can be revelatory; artist residencies may be supercharged incubators for creativity, but it is the electric interactions and inevitable aftershocks that yield the most fascinating or complex results.

My first international artist residency took place at The Vermont Studio Center (VSC) in May 2013. The month in Vermont was transformative, because I had the freedom and peer support to experiment with materials and media. I made my first video work there, and I have continued to incorporate this medium into my practice. Like when I travelled to the UK for my education, however, there were moments of hyper-awareness of my “otherness” as being the only resident from the Caribbean. There is a certain self-consciousness, as suddenly you can find yourself as an unwitting ambassador for your country, or even the whole region.

Trinidadian artist Shanice Smith also shared this sentiment when reflecting on her VSC residency six years later: “How much of my “Caribbean-ness” would I have to tone down to accommodate folks? I mean, I came here with an open mind—do not be mistaken. It’s just a matter of mentally preparing how conscious one has to be when it comes to slowing down one’s accent, mannerisms and movements so that others can understand you.”[2] This can create a level of pressure that is counter to the general ethos of residencies as spaces that free the artist of certain obligations; the current can change direction, resulting in an unforeseen shift in responsibilities as opposed to a complete release.

On the other hand, the questions and tensions of being in foreign environments can inspire new projects. Out of Smith’s time at VSC, she began exploring the power of food and sharing meals as a coping mechanism to deal with feelings of displacement, and to broach conversations about cultural differences and connections. This led to her eventual formation of Cousoumeh Collective, a social practice initiative we collaborate on.

While these shared experiences are common among Caribbean artists, it is worth noting that mobility within the region, which can be an extremely convoluted and expensive affair, despite the islands’ proximity to one another, can be just as eye-opening or jarring. On her 2016 participation in the former Caribbean Linked residency programme in Aruba, Guyanese artist Dominique Hunter said “Nothing about Aruba was familiar to me. The absence of traffic congestion and the road rage that would surely follow; no loud music blaring from cars as they drove through neighbourhoods; a fascinating juxtaposition of beautiful flat houses and towering, monstrous hotels; fields of intimidating cacti, thorny bushes and the largest species of aloe I’ve ever seen; the diversity of their languages and the incredible support available to creative practitioners, or any student for that matter, all underscored how little I knew of this island.”[3]

Regional residency opportunities such as this underscore what makes the pressure to exhibit “Caribbean-ness” when abroad such an impossible task. The Caribbean is far from monolithic when it comes to culture, so how can a single person represent a whole country, let alone archipelago? The interplay of the foreign with the familiar, negotiating unexpected similarities and differences generates its own dynamic, usually one of mutual understanding and appreciation for this diversity and layered interconnectedness across our islands.

“Placing expectations of belonging on a country can be a heavy burden…”

Conversely, international artists who venture to the Caribbean may have incentives that range from aesthetic to deeply personal. As I spent more time in the role of residency facilitator at The Fresh Milk Art Platform in St. George, Barbados, rather than artist-in-residence, I observed a pattern of Caribbean diasporic artists choosing to come to the Caribbean as a way to connect with their heritage. Coming from Global North centres where racism, xenophobia, and prejudice frequently marginalise people and communities that have every right to the space, it is understandable that a desire to belong and explore facets of identity would be the impetus for coming to the region.

Identity and culture are nebulous and ever-changing, which make them some of the most challenging subjects to unravel. There may then be a disconnect when members of the diaspora, whose concepts of the Caribbean are sometimes based on nostalgic or outdated views, enter a space that does not necessarily meet their preconceived notions. Placing expectations of belonging on a country can be a heavy burden, as by extension it can set the inhabitants up to fail a test that they did not elect to take. This is not to say that the exploration of roots is a negative thing—it can be powerful, cathartic and enlightening when approached with an open-mind and mutual respect. As Stuart Hall said, “Identity is not as transparent or unproblematic as we think. Perhaps instead of thinking of identity as an already accomplished fact, which the new cultural practices then represent, we should think, instead, of identity as a ‘production’, which is never complete, always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation.”[4] Artists who travel in hopes of solidifying or consolidating their identity on the basis of geographic location or borrowed memories, are more likely to discover this ongoing process rather than reach a fully-formed resolution.

Canadian-Barbadian artist Jordan Clarke, for example, said of her time in residence at Fresh Milk, “Over the past week, I have been thinking about identity and how it is shaped. I realize now that my sense of identity is not linked directly to Barbados, despite my father’s Bajan roots. This is the perfect opportunity for me to think about how I would like to identify, how I see myself, as well as how my life experiences have shaped me.”[5] Her poignant and vulnerable position reinforces identity as a personal journey and the sum of many parts.

Another artist-in-residence, Guyanese-American artist Damali Abrams, spent time at both Fresh Milk and with the then-active collective Groundation Grenada in 2013. Whilst in Grenada, she took part in a public performance piece addressing issues of the treatment of pregnant teenagers in the public school system, and shared a sensitive reflection on her own position in the public sphere, and the position of the audience: “There was a certain level of freedom performing in a place where I don’t know anyone … I also didn’t know if as an outsider I had a right to claim this space and comment on these issues in someone else’s country and community. Those issues remain unresolved for me, but I feel inspired to find ways to continue this kind of work wherever I am.”[6] When there are stakes involved for both the artist and the wider community, asking questions, listening actively, and remaining self-reflective and reflexive are key components to any cross-cultural engagement.

The law of conservation of energy states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed, only converted from one form to another. Having taken part in and hosted residencies for over ten years, I have been energized, depleted, and recharged time and time again. You cannot know until the very end how all factors (social, physical, emotional, environmental, etc.) will come together, whether you are the one leaving your comfort zone, or the one welcoming others. Hall referred to “the Antillean as the prototype of the modern or postmodern New World nomad, continually moving between centre and periphery.”[7] This makes sense in relation to Caribbean and diasporic people’s inexorable navigation of space. The ebb and flow of cultural exchanges is critical. If a circuit is correctly assembled, points of contact serve to ignite growth and ingenuity, whether internally for the artist or externally for the community into which they have temporarily been plugged-in.

[1] Maria Rita Pinto et al., “Artists Residencies, Challenges and Opportunities for Communities’ Empowerment and Heritage Regeneration,” Sustainability 12, no. 22 (November 2020): 9651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229651.

[2] Shanice Smith, “VSC Blog – Week One,” Shanice Smith Artist, May 20, 2019, https://shanicesmithartist.wordpress.com/2019/05/20/vsc-blog-week-one.

[3] Dominique Hunter, “Dominique Hunter – Caribbean Linked IV Artist Text,” Caribbean Linked, August, 2016, https://caribbeanlinked.com/editions/caribbean-linked-iv/artist-texts/dominique-hunter.

[4] Stuart Hall, “Cultural Identity and Diaspora,” in Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, ed. Jonathan Rutherford (Lawrence & Wishart, 1990), 222.

[5] Jordan Clarke, “Jordan Clarke – Residency Blog,” Fresh Milk Barbados, April, 2015, https://freshmilkbarbados.com/writing/residencies/jordan-clarke.

[6] Damali Abrams, “Damali Abrams – Residency Blog,” Fresh Milk Barbados, October, 2013, https://freshmilkbarbados.com/writing/residencies/damali-abrams.

[7] Hall, “Cultural Identity and Diaspora,” 234.

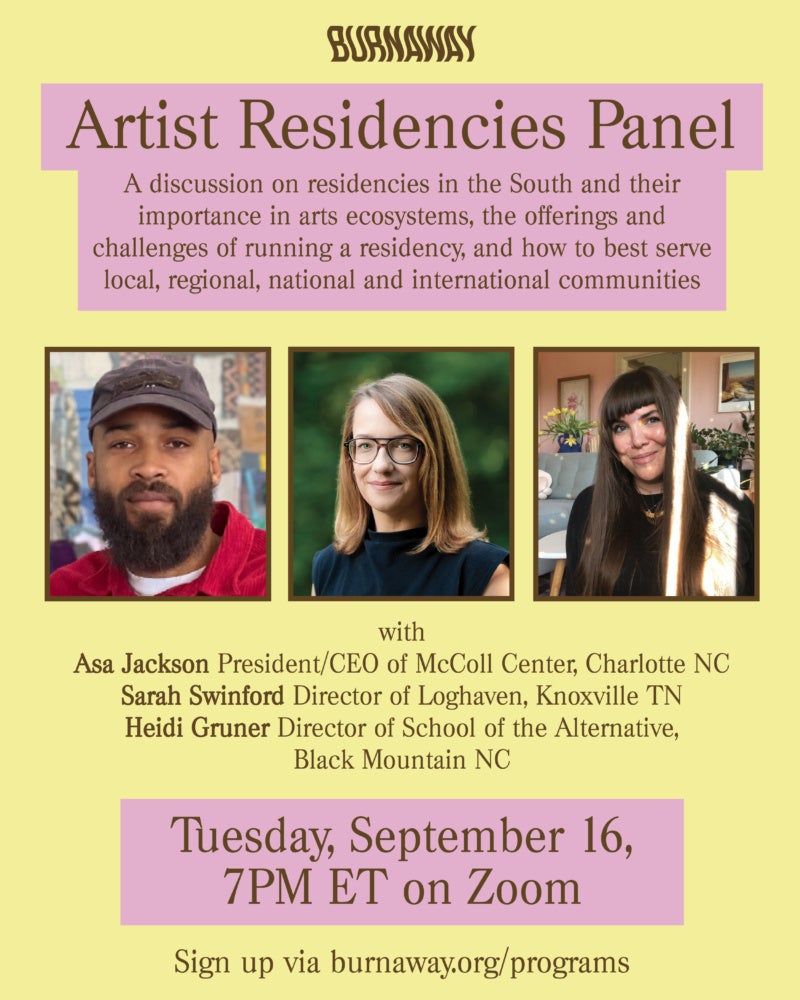

Join Burnaway on Tuesday, September 16 at 7PM ET for a virtual panel on artist residencies in the South. Our Editor and Artistic Director Courtney McClellan will be moderating a conversation between Asa Jackson, President/CEO of McColl Center, Sarah Swinford, Director of Loghaven, and Heidi Gruner, Director of School of the Alternative. We’ll hear about what it’s like to run artist residencies in the South, their importance in arts ecosystems, the offerings and challenges of running a residency, and how to best serve local, regional, national, and international communities. They’ll also discuss what it’s like to bring artists from around the world to the South.