Tracing the artist’s journey through a collection of over 150 objects, including painted canvases, works on paper, sculptures, and a range of ephemera, Alma Thomas: Everything is Beautiful recounts the intricacies of the inimitable modern artist’s life. Co-curators Dr. Jonathan Frederick Walz, Director of Curatorial Affairs and Curator of American Art at The Columbus Museum and Dr. Seth Feman, the Chrysler’s Deputy Director for Art & Interpretation and Curator of Photography successfully reflect the enormity and complexity of Alma Thomas’ life and work, from her upbringing in the Jim Crow South to her rise to international acclaim. Unlike previous retrospectives that commonly focused on Thomas’ late career, Alma Thomas: Everything is Beautiful uniquely delves into every facet of the pioneering Black female artist and uproots entrenched, linear narratives to emphasize her longstanding, multidimensional creative career.

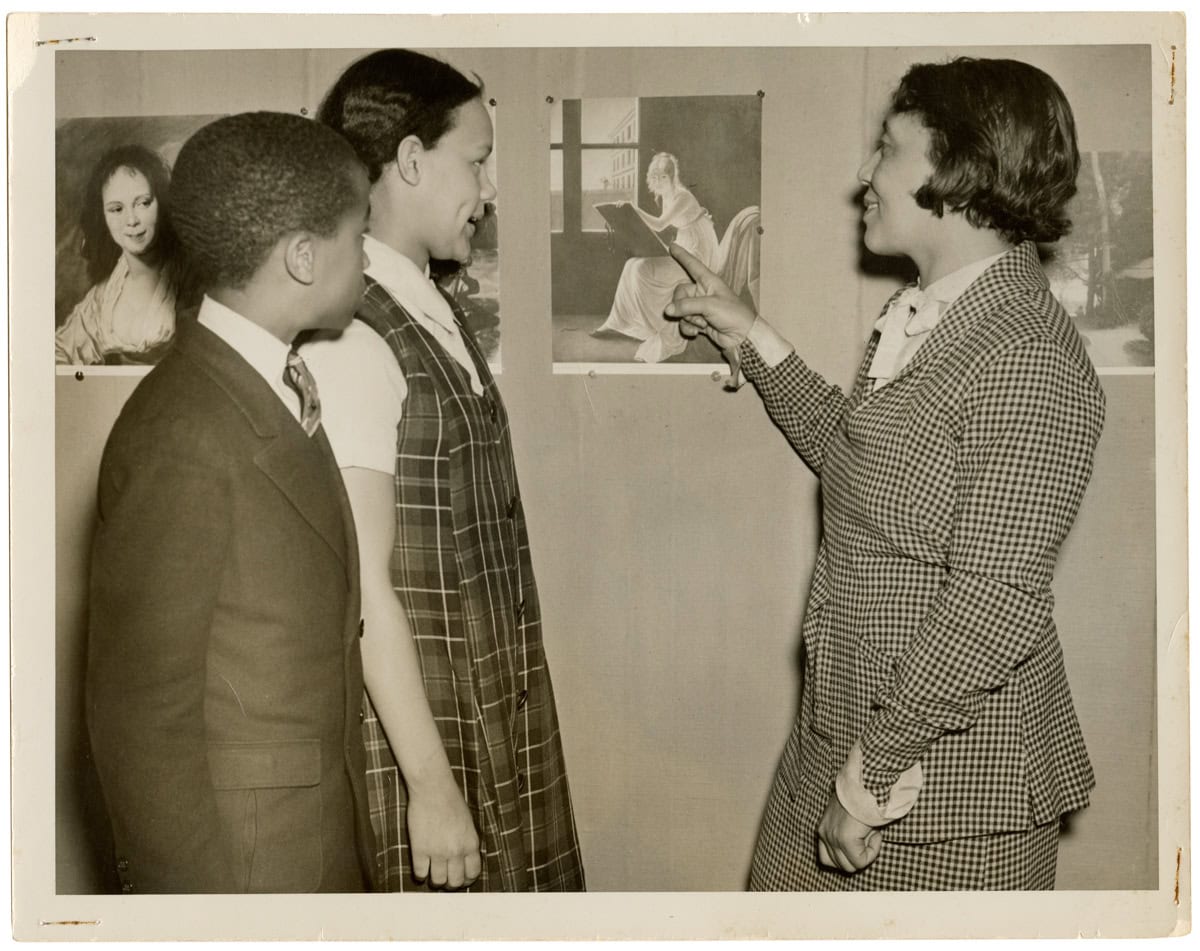

Born in Columbus, Georgia in 1891 and later moving with her family to Washington, DC in 1907, Thomas embraced a love for nature at a young age that would influence her practice, later recalling early memories of her family’s home garden, her grandfather’s Alabama estate, and the urban green spaces of the capitol. In the 1920s, she attended Howard University originally as a major in home economics and costume design, but was soon persuaded to transfer to the visual arts department and later became the University’s first art graduate in 1924. While pursuing her studies as a master’s student in art education at Columbia University in the early 1930s, she dedicated herself to enriching the lives of young people, teaching at DC’s Shaw Junior High until her retirement in 1960. Having an uncompromising commitment to education and deep investment in the city’s artistic milieu, Thomas initiated Howard’s School Arts League in 1936 to promote the work of young, Black artists and quickly became an avid member of the capitol’s first Black-owned gallery, Barnett Aden Gallery.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Thomas returned to the classroom, this time as a student at American University, where she was introduced to modern abstract styles and became acquainted with notable artists Robert Franklin Gates and Jacob Kainen. It was not until 1966 at Howard University that she held her first solo exhibition during which she debuted her signature style: the “Alma Thomas Stripe,” an arrangement of vertical bands of staccato brushstrokes made from colorful, diluted acrylic paint. This style was developed during the emergence of the Washington Color School, a loosely affiliated group of painters including Morris Louis and Sam Gilliam, who applied luminous, bold touches of color by staining and soaking acrylic paint onto canvas. Despite not having exhibited with the original group in its 1965 exhibition at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art where the collective’s namesake was coined, Thomas was eventually associated with the group by scholars years later due to her abstract color compositions and ultimate befriending of some of the group members.

By 1972, after tense protests over the Whitney Museum of American Art’s lack of racial diversity, both in terms of its internal staff as well as its roster of artists, Thomas was selected to be the first Black woman to present a solo exhibition at the museum, a moment dubbed as her crowning achievement. Lauded as a triumph over racism, sexism, and ageism, the career-making exhibition unquestionably and ubiquitously promoted the artistic genius of the now 65-year-old artist. For the remaining years of her life, even after suffering from arthritis and other physical impairments, Thomas continued to push her creative expression, developing and innovating her artistic style up until her death in 1978.

Alma Thomas: Everything is Beautiful unfolds into thematic sections beginning with the artist’s 1972 Whitney solo exhibition, then segueing to her studio and pedagogical practices; the importance of gardening within her work; her artistic network; and lastly, her late career. In doing so, the exhibition simultaneously functions as both a biographical and myth-busting endeavor, underlining a life-long existence of artistic ventures and disrupting her canonically prescribed identification as an artist who only blossomed late in her career and life.

The first section restages roughly two-thirds of the works originally shown in Thomas’ 1972 Whitney solo exhibition. Immediately, audiences become acquainted with both Thomas’ iconic colorful, abstracted-pointillist paintings and her whole-hearted embodiment of her art, as seen by the mannequin donning the color-block dress she wore at the opening. More poignantly, however, visitors are confronted with the trials and tribulations endured by art professionals of color during the mid-twentieth century. Presented alongside the works are archival photographs of protestors and correspondences between the Whitney and social activists, like the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), who proposed the equitable display of artists of color as well as the consultation of Black art professionals during the development of African American and African Diasporic art exhibitions. These materials juxtaposed against the artworks on display demonstrate Thomas’ plight as a Black artist wherein public-facing activism by artists themselves and external groups seemed one of the only means toward institutional representation.

Additionally, this space exemplifies the continuous contradictions and wrongful accreditation within the art historical discourse which undermine the significance of artists and curators of color. For one, it reveals how the Whitney, a predominately white institution (PWI), commonly and unjustly receives primary credit for a Black artist’s career trajectory. Two, the space promptly emphasizes said PWI’s overshadowing of Thomas’ Black colleague and curator, David Driskell who not only was one of the first to support her work, but also laid the curatorial groundwork for the Whitney exhibition in a 1971 Fisk University exhibition just prior to the New York presentation. While surely Thomas is due all credit for her infinite achievements and persistence, this particular section of Alma Thomas: Everything is Beautiful reminds us that it is imperative—and at minimum responsible scholarship—to properly acknowledge those who played key parts in Thomas’ success as well as those who incurred hindrances.

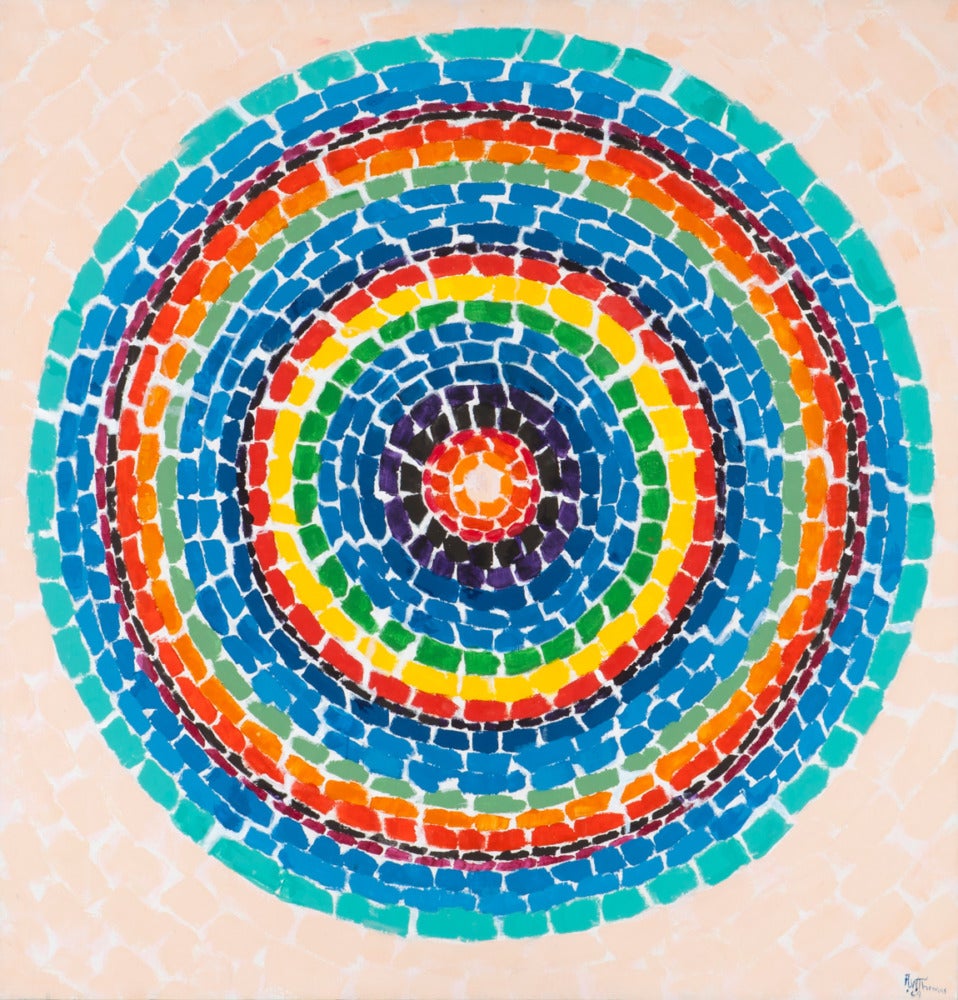

The proceeding gallery traces Thomas’ process and studio, featuring a wall of paintings that track her transition from figuration to abstraction; a vitrine displaying her ink-blot watercolors; and a corner vignette of art objects, books, and modern home furnishings from her studio that ultimately informed her practice. Just opposite is a salon style hanging of Thomas’ works further identifying her keen attention to color theory and experimental trials towards the “Alma Thomas Stripe.” Untitled (1968), in particular, unveils her initial process, at first cutting and layering vertical strips of paper to create a harmonious composition of colorful broken brushstrokes.

Two later galleries in the exhibition investigate gardening as Thomas’ pastime and inspiration, as well as the interdisciplinarity of her teaching methods of which were firmly rooted in her love of fashion and theater—a relatively underrecognized narrative. Thomas’ immersive, overflowing gardens, as seen in the presentation of Thomas’ personal photographs, served as reference for her paintings. Babbling Brook and Whistling Poplar Trees Symphony with its flowing, concentric gestures of blue acrylic that engulf the entire canvas, not only recount the waterways surrounding her childhood home but recall the multisensory, lush floral oases Thomas cultivated and visited. Feman and Frederick also demonstrate the depth to which her appreciation of theater seeped into all aspects of her life, from her self-fashioned wardrobe to the ways in which marionettes played into her classroom curriculum. Inspired by her master’s research which investigated the benefits of using puppeteering to bridge language arts, history, anatomy, design, sewing, woodworking, music, and more, Thomas encouraged her Shaw Junior High students to develop marionettes, some of which are on display alongside Thomas’ costume design sketches and puppet drawings. Each section honors the ever-evolving state of Thomas’ creativity and underscores the interconnectivity between her profession as an art educator, her personal histories, and her studio production.

The subsequent galleries situate Thomas within the vast artistic circles she became associated with throughout her lifetime, including her peers in the “The Little Paris” group, colleagues at American University and Howard University, as well as a handful of members in The Washington Color School. Thomas was heavily influenced by the Phillips Collection, particularly after its 1955 acquisition of Paul Cezanne’s Le Jardin des Lauves. In the words of the artist: “Cezanne’s unfinished painting of a landscape at The Phillips Collection gave me the idea of using color to structure a painting…Painting all over the canvas rather than just drawing, he gave an architectural structure to color.” The juxtaposition between the works of Cezanne and Thomas pinpoints the Impressionist’s influential patchwork techniques upon Thomas’ practice.

This reflection on artistic circles and influences is not purely about pure kinship, however. The proceeding gallery presents two dueling walls that display works by members associated with the Washington Color School—on one side, paintings by Alma Thomas and on the other, those by Gene Davis, Sam Gilliam, Morris Louis, and Kenneth Noland. From the outset, the boast of vibrant color exuding from all the canvases plainly demonstrates the groups’ common exercise of color theory through minimal, yet intentional gestures. However, this mirroring of work has the effect of upheaving the longstanding pigeonholing of Thomas with the modern Washingtonian collective. Compared to the hard-edge paintings of her Washington Color School contemporaries—who were 30 years her junior, male, and predominately white—Thomas’ pieces stand out in their lighter touches of color from a softer palette and evoke a sense of the organic, undoubtedly connected to her relationship with nature.

Applying an astute curatorial strategy, these sections not only outline Thomas’ development from her figurative, representational tendencies to her signature style which resulted in her alignment with the Washington Color School; but more importantly, they emphasize Thomas’ incomparable, powerful ability to seamlessly transgress various social circles and artistic painting practices—the likes of which were often distinct, segregated, and male dominated.

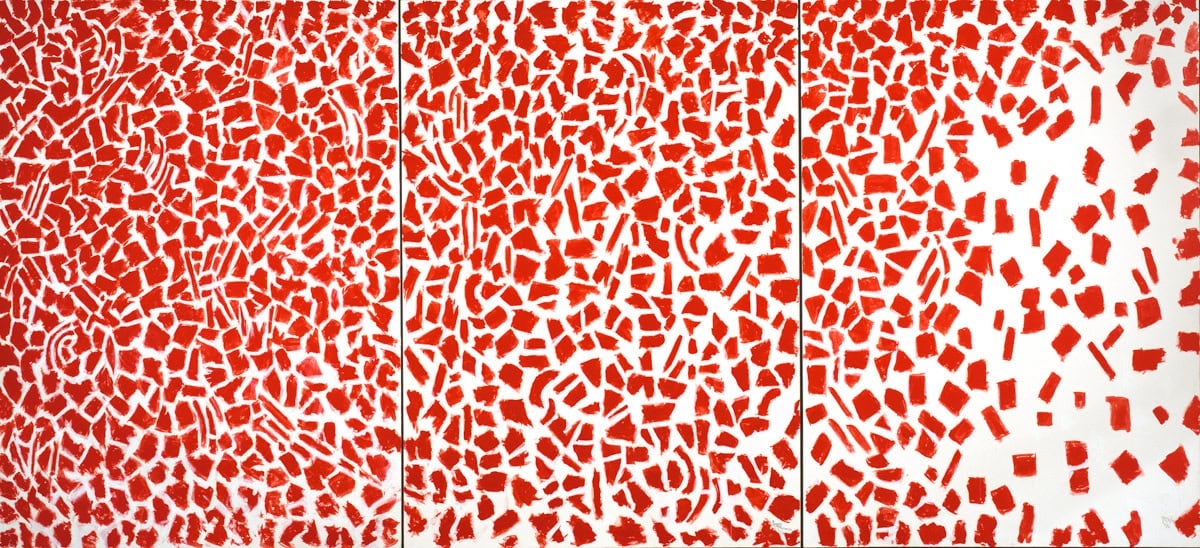

The exhibition closes with a selection of works created towards the end of Thomas’ life, accounting for her continued pursuit of beauty. The capstone work, Red Azaleas Singing and Dancing Rock and Roll Music (1976),a wide triptych canvas depicting a gradually dispersing field of red dots toward a blank space, is a particularly poetic curatorial gesture as it both visually and metaphorically reflects Thomas’ transition away from her iconic style, and represents her continuous ambition to create up until her dying day. Gracing the left side of the canvas are traces of Thomas’ traditional repetitive, rhythmic brushstrokes and meditations on nature akin to her earlier works such as A Joyful Scene of Spring (1968). The dabs of red paint then gradually scatter from a dense field into an empty space on the canvas’ opposite end, mirroring a gradient-like technique seen in her later monochromatic, floral paintings like Babbling Brook and Whistling Poplar Trees Symphony (1976). Red Azaleas projects a seemingly new venture during Thomas’ last years where she allows larger negative, white spaces to breathe through.

Opening at the crux of resurgent international movements for racial equity and major institution-wide overhauling to reckon with decades of racial exclusivity, Alma Thomas: Everything is Beautiful is a keen reminder of the ongoing racial injustices within and without museum walls. The mere sight of the first gallery, which demonstrates Thomas’ tokenized experience at a moment of institutional reckoning nearly a half century ago, underscores that the current movement for equity in institutions has been moving at a glacial pace. Yet, Alma Thomas: Everything is Beautiful astutely outlines that, in Thomas’ wake, a legacy of opportunity was born for artists of color and inspired an institutional embrace of Black female artists – as seen with the recent selection of Simone Leigh for the United States pavilion in the 2022 Venice Biennale.

Remaining vigilant and aware of Thomas’ impact, the exhibition importantly divests from canonical prescriptions and metrics of success that commonly undervalue her individualism and abilities, and purely centers her as a formidable artist who forged her own path toward achievement and celebrity. While honestly demonstrating the hardships that Thomas faced, Alma Thomas: Everything is Beautiful rightfully paints her life as a beautiful endeavor, filled with people and places she cherished, a community that respected her, and an endless, fulfilling passion for art that has gifted the world for years to come.

Alma Thomas Everything is Beautiful will be on view at The Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, VA until October 3, 2021.