A week after 2018’s International Women’s March, Burnaway is reflecting on women’s roles historically and the importance of intersectionality in today’s universal feminist mindset. Today, we take a look at artist Tia-Simone Gardner’s recent exhibition at the Ground Floor Contemporary Gallery in Birmingham and its significance in representing a vernacular history connected to societal roles of African American women.

Tia-Simone Gardner’s exhibition She Ain’t Gone Nowher’ opened at Ground Floor Contemporary Gallery in Birmingham on January 4. It was open to the public on most Sundays in January, with a series of artist talks each week.

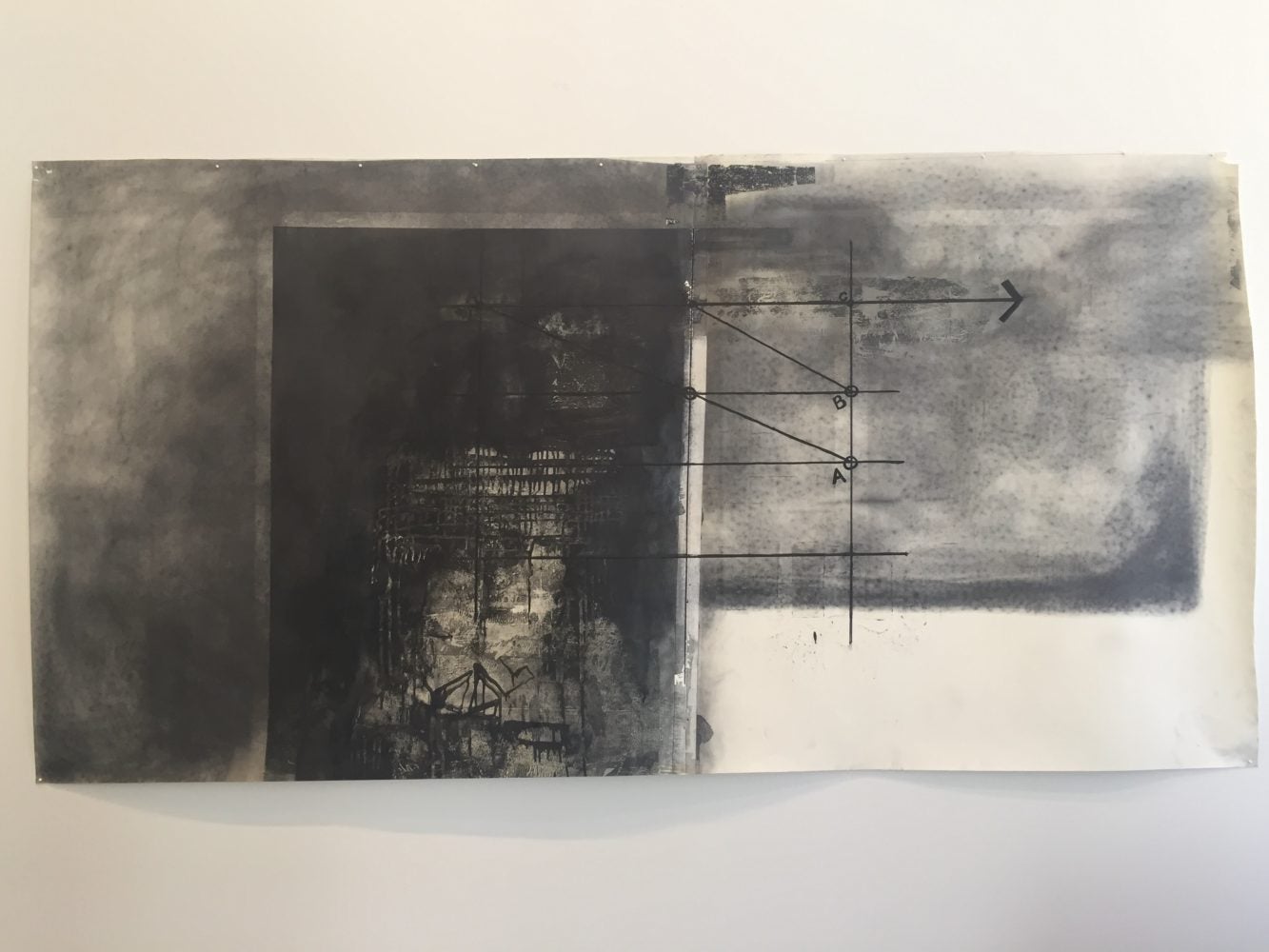

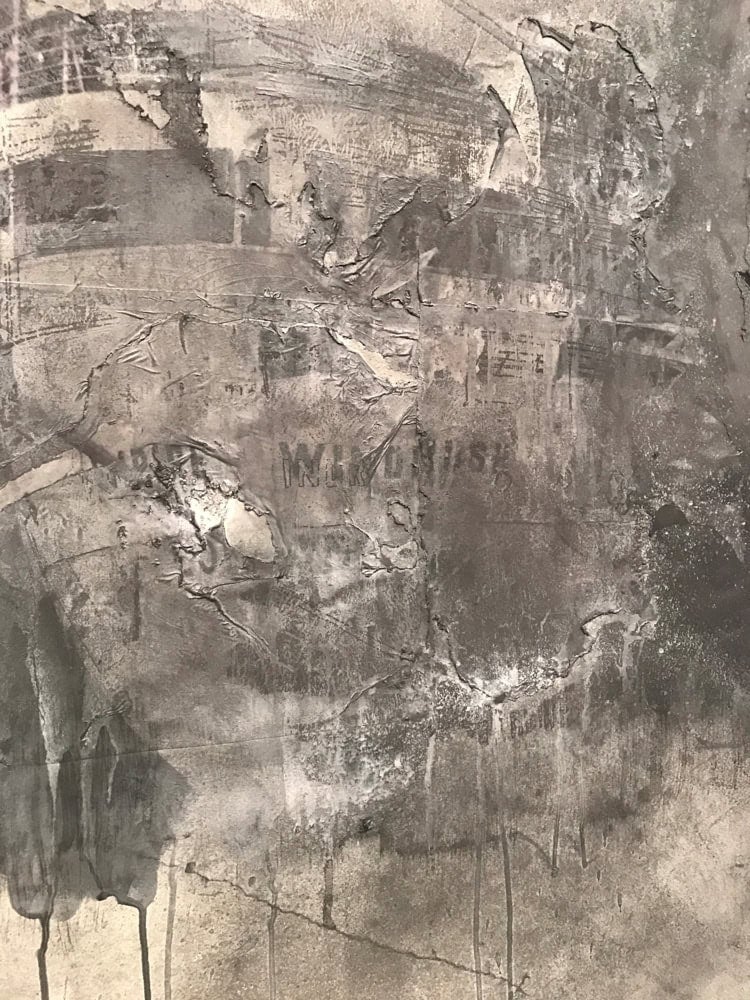

In She Ain’t Gone Nowher’ Gardner draws on black feminist writing and activism to explore relationships between race, geography, history, space, and place. She works in hybrid drawing, photographic, text, and time-based methods to create dense, layered images in a black and white palette that are simultaneously revealing and cryptographic. Her subjects include escaped slave Harriet Jacobs’s attic hideaway, South African activist Winnie Mandela’s jail cell, Ousmane Sembène’s film Black Girl, and the voyage of the ship the Empire Windrush from Jamaica to England, which marked the beginning of postwar West Indian immigration to the U.K. Gardner prompts us to imagine these places both literally and figuratively. In so doing, the artist suggests how “space can be produced as toxically gendered and racialized, often in ways that are illegible.” Gardner, who is from Birmingham, holds an MFA from the University of Pennsylvania and an MA from the University of Alabama. She is currently a PhD candidate in Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Minnesota. I sat down with Gardner to talk about the exhibition’s themes and her current existence as a transient artist.

Jessica Dallow: So, to start, can you talk about the title of the exhibition, “She Ain’t Gone Nowher’”? Is that about you coming back here to Birmingham?

Tia-Simone Gardner: It’s partly about me. It’s also partly about episodes when black women are both hyper-visible and invisible at the same time. That someone could be present in front of you, but you could not see them. And all of these stories are a part of this, like Harriet Jacobs hiding in her grandmother’s attic for seven years. Or Winnie Mandela writing a diary on toilet paper from prison that wouldn’t be found until she was released.

JD: How has your dissertation research informed your art-making?

TSG: My dissertation is about tiny houses, mobility, equity, and race. I’m creating a mobile artist residency program—we don’t have a residency program in Minneapolis. It is a cheap city and there are artists who would like to work there. I work for an organization where I program visiting artists and I started working on getting funding for a mobile artist residency. And I’ve been writing about how to get a city to say yes to such a thing.

I am also interested in how black people had never been proper architectural subjects, yet have designed habitations for themselves that worked for the lives they wanted to live. And how scale is used; or how space is used or underused.

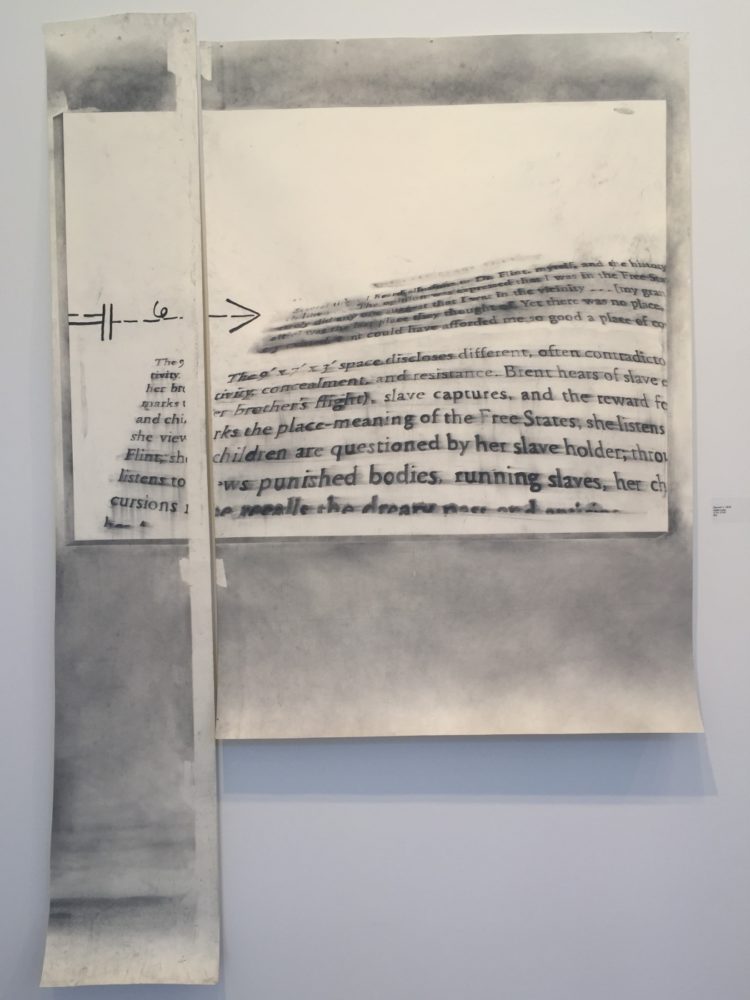

JD: What is the text in Garret I, 1833 excerpted from?

TSG: The text [which is about Harriet Jacobs’ 9’ x 7’ x 3’ attic hiding space] comes from Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle by Katherine McKittrick. It’s been deeply informative to how I’ve been thinking about place and time. She’s Canadian, but she’s writing about auction blocks and garrets and using specific language to do this. She thinks about geography very differently than the discipline of geography generally does.

JD: How do you reconcile space and place? The works here aren’t about mapping space, but more about tangential connections to place?

TSG: I think what I have gleaned from McKittrick is that cartography tells us that you can map a thing. You can locate Birmingham on a map. But Birmingham is, and this is watering it down of course, a set of relationships. You say Birmingham and it conjures up a series of things for people. They might not be able to draw it or locate it. But cartography would tell us that we can map things—a form of representation—and therefore know that thing. McKittrick discusses how representation has deceived us in ways that make black folks unplaced. The diaspora has dislocated black people and told us we were shifted and stolen and there is nothing that we can claim as a place. So how do you unbind blackness from being a dislocated thing?

What does it mean to just exist as a dislocated thing? There’s a thing about being mobile—I’m doing a residency in New Orleans after I leave here—that makes me uncomfortable because I know how that can be read. Or that people understand something. When you’re static you can say where you live or where you’re from.

JD: The dates here and the locations—1789, 1833, 1969, Kingston, London, the U.S., South Africa—map the Black Atlantic. But there isn’t a specific narrative or linearity. Was that intentional?

TSG: That’s right. I don’t think linearly. I think in an assemblage of things. It’s funny that the Black Atlantic is so embedded in what gets made, in literature, in film, in art. It can’t help but continue to show up, even in the haphazard. So, yes, the Atlantic is there. And it’s very important, but that’s not the whole story.

The works connect to a lot of different stories. The drawing Kingston Harbour, 1948, I came about from reading about Claudia Jones, who was deported from the U.S. in 1955. She was secretary for the [Women’s Commission of the] Communist Party USA. I was interested in her because she was originally from Trinidad. She gets deported to England, not to Trinidad. She wanted to go to England. She is the person who started the Notting Hill Carnival, after the riots. She was trying to find a way to humanize black people in the U.K. In 1958. And she uses art to do this—parades and pageantry from the Americas. So I came to the subject of this drawing through Jones, and thinking about the population of West Indians in the U.K. and how many of them got there, on the ship [the Empire Windrush].

JD: If you are talking about space and geography, why is it that you are focused on two-dimensionality?

TSG: For the longest time I was trying to be a draftsperson and what drawing meant was very limited. I am trying to open that up. The drawing Garret II, 1833, made of salt on wood, is more sculptural, and displayed horizontally. I was influenced by Voodoo rituals where you make the drawing on the ground or Buddhist sand mandalas—by drawing practices that are spatial. And I try to talk about him as much as I can, but I had a professor who recently passed, Terry Adkins (1953-2014), who was a sculptor, and I have been trying to think more about my relationship to his work. He worked in sculpture and performance.

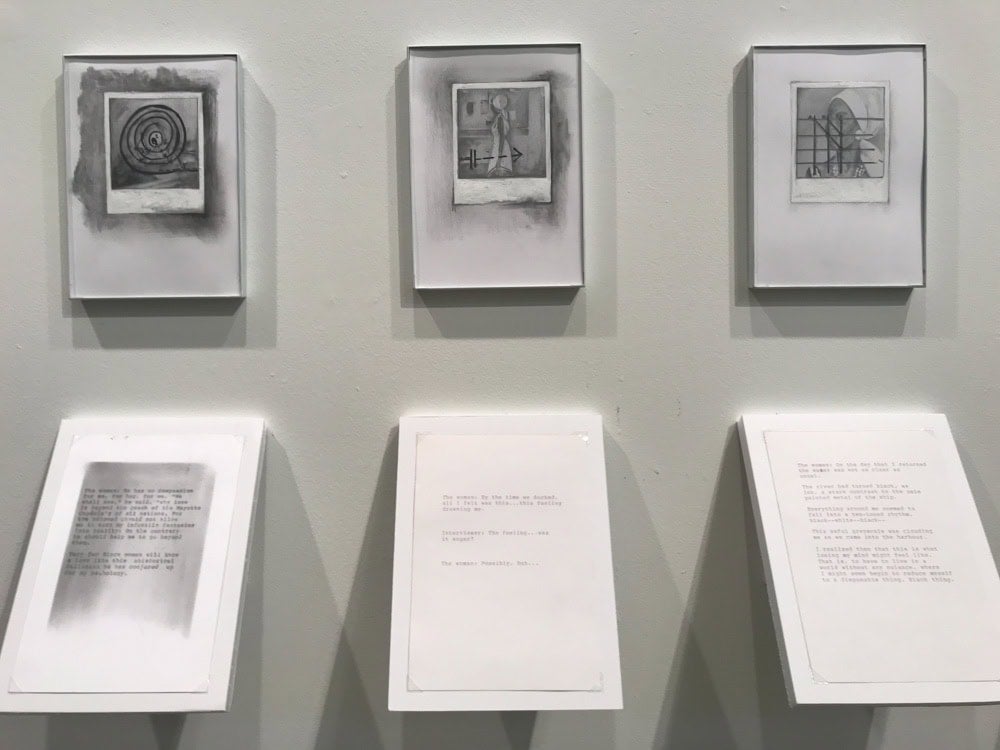

JD: Tell me about Neither One, or Somewhere In Between, Version II.

TSG: What it is a person who works with drawing trying to make a film. Or a person who works with photographs trying to make a film. I’ve been trying to take apart Ousmane Sembène’s film Black Girl [1966]. In French, it is Le Noire de…, which literally translates as “Black Girl of.” He titled it that way because the girl is this sort of generic “she ain’t gone nowher” kind of figure. She could be from anywhere. The film haunted me for a long time and it was recently digitized and thus more widely available. I made it into a bunch of stills. I took it apart and started looking at the spaces in the film, one of which is an apartment.

JD: And here you’ve drawn the film frames to look like Polaroids.

TSG: Yes, each is a drawing where the process is quite slow, but of a film frame, an instant. And below is my text—the film’s subtitles, describing the scenes. This is an analog way of thinking through the film I’m making. The subtitles are presented like a document. In the film they show up as intertitles. And, there is also an excerpt from Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, printed on pink carbon paper to resemble a prescription pad. Fanon writes about the black woman’s desire for the white man, but he completely eviscerates her. She’s there and then she’s not there. So I was using Fanon as a way to write through the film.

JD: Tell me about your use of carbon paper.

TSG: I was using it as a means to an end. I had been using photographs and carbon paper to make drawings. In Kingston Harbour, I used a photo transfer for the image of the freighter, then I used carbon paper to make a second drawing. So it’s layers. I like using carbon paper because you have to do it blind, you can’t always see what you’re doing.

I started experimenting more and made rubbings. I used the digital lab, first laser cutting a drawing, then I would lay the carbon paper on top and do a rubbing, so you get a low relief image. But I like how subtle they are, although they are hard to photograph well. I’d like to experiment with making my own carbon paper, maybe even with BBQ soot and ash.

JD: How are you thinking about shape? The small studies especially can be read on a purely formal level—black on black—like a Frank Stella or Ad Reinhardt. And even many of the works include elements of the grid.

TSG: The grids and directional lines come from Deleuze and Guatarri’s A Thousand Plateaus.

It made sense to try drawing with their drawings. I have always been aligned with abstraction, even though early on I was making representational work. I thought that was what I was supposed to do, make images of black people.

The square, or rectangle, is like a container box. So, the shape and the edges also connect to the subjects. As I experiment with making my own carbon paper, everything may change. But I did go to architecture school first, so maybe there is something coming through here from that experience. Complicated histories.