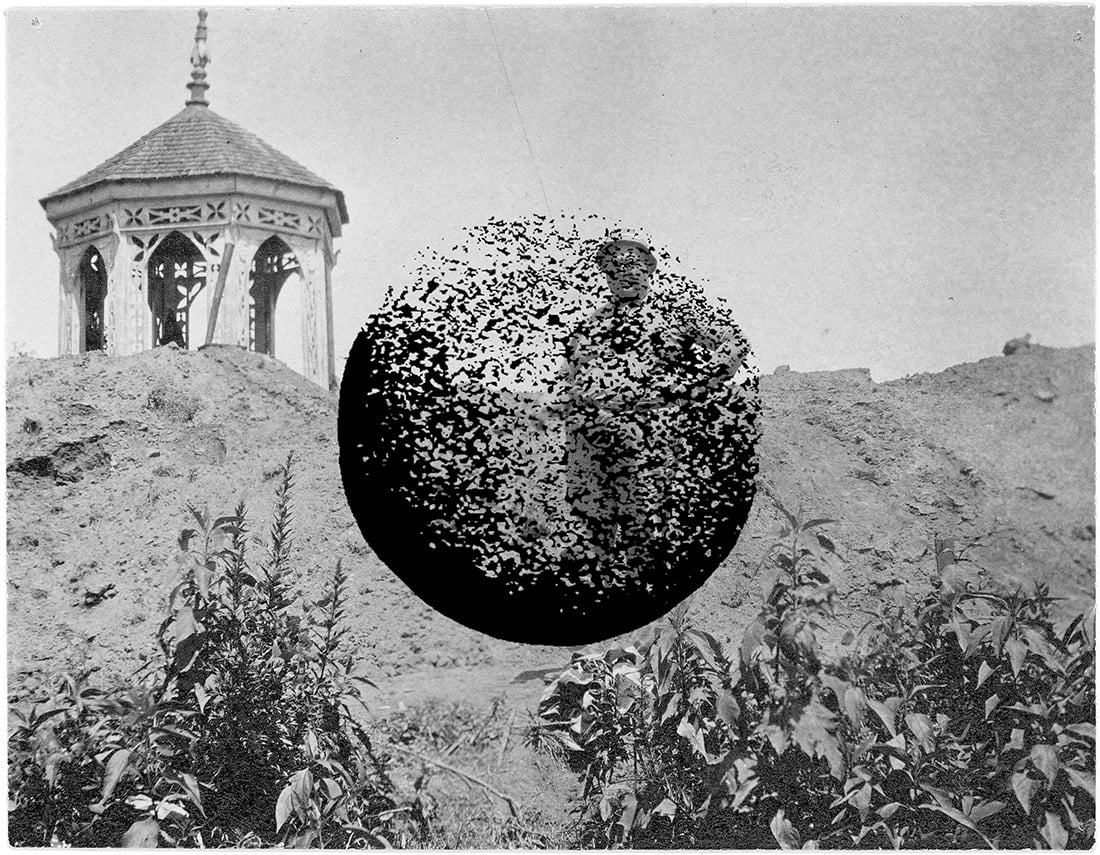

It’s the charm of Bavaria, in the heart of the Blue Ridge Mountains, reads the tagline on the official website of the town of Helen, Georgia. In contrast to the bustle of Atlanta about a hundred miles southward, the bucolic mountains surrounding Helen are home to some of the Southeast’s most beautiful national forests. At dawn, their valleys, carved over millennia by the Chattahoochee River, are often covered in a heavy mist. A cluster of exaggerated Fachwerk structures, appearing like a gingerbread village, peeks above this mist: the towers and spires of the town of Helen. As you drive into Helen from Atlanta, you pass the Nacoochee Mound, an ancient Native American burial mound topped with an ornate nineteenth-century gazebo.

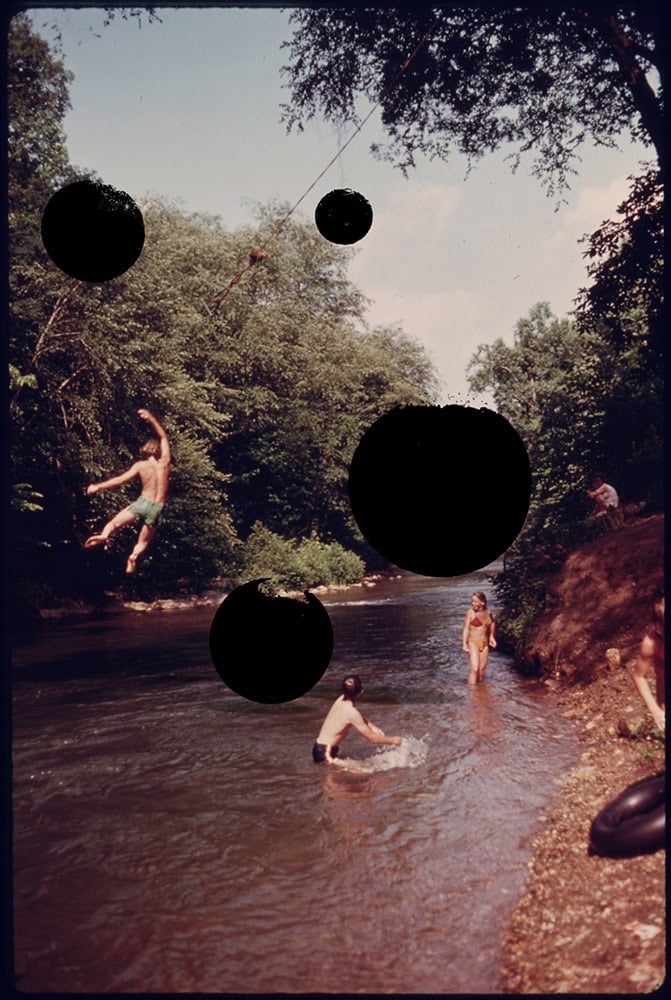

In 1969, North Georgia artist John Kollock, remembering his time as a soldier in Germany during the Second World War, envisioned transforming sleepy Helen into an idealized alpine village. Business owners in Helen, looking for a way to revive the town, supported Kollock and his vision, as he had already made a name for himself as an artist-historian who recreated local historical scenes in watercolors. In less than a year, using Kollock’s paintings as blueprints, they constructed and revealed the neo-Bavarian town to the world. The number of downtown businesses tripled within three years; tourism soared. Fifty years later, an estimated three million visitors pass through Helen’s candy shops, drink at its beer halls, play mini-golf on its courses, and float down its river in bright inner-tubes—generating around $100 million in revenue each year.

Underneath its saccharine façade, Helen is not the candy land it prides itself to be, nor are its buildings innocent gingerbread houses. Its white stucco “icing” is, in truth, a whitewashed, ahistorical veneer. Before Helen took on its ersatz alpine form, these mountains were invaded, plundered, and commodified until they were left barren. The area’s original inhabitants, the Cherokee, were murdered and removed, and enslaved people were brought in as forced labor in the name of profit. Yet, today, one would be hard-pressed to find much account of any of that history when visiting the area.

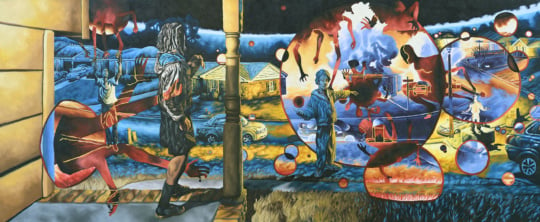

Helen is tucked into the southernmost end of the Appalachian Mountains, of which the Blue Ridge Mountains are a part, in one of the most biodiverse, temperate ecosystems in the world. Landscapes are perceived as being completely natural and, therefore, generally neutral. When inspected closely, the landscapes of North Georgia show clear evidence of profound, man-made ecological trauma. The state of the landscape surrounding Helen today is the product of a string of devastating ecological disasters resulting from the influx of colonial settlers at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Unregulated hydraulic mining tore the ground apart during the Georgia Gold Rush of 1828, washing away entire mountains as prospectors searched for gold. Once gold became scarce, the same settlers and many new arrivals began cutting down trees and exporting lumber. The rise of the logging industry coincided with—and profited from—a disastrous chestnut tree blight, during which nearly four billion American chestnuts across the Appalachian Mountains, many of them centuries old, died in the first quarter of the twentieth century. When Helen was founded as a logging town in 1912, the surrounding landscape had already been irreparably altered. Most of the remaining trees were felled in the years leading up to the Great Depression, when loggers moved on to more promising forests elsewhere. By 1930, a place once lush and green had been left so bare that spots served as backdrops for Western films. Out of this barren terrain, marked with mangled tree trunks and exposed red clay, a new landscape would emerge, one fundamentally molded by colonial arrogance. The forces of white supremacy in the area operated, correspondingly, as a fabricated ecology: amnestic and profit-driven. As the foundational acts of abominable violence became historicized, genocide and slavery were addressed with thinly veiled apologies or altogether forgotten, and the structures of inequality and oppression began to appear as a normalized landscape that, perceived as neutral, receded into the background.

Outside of Helen, there is a small area where drivers can pull over to look at the gazebo-topped Nacoochee Mound and read the short text on its historical marker. There are many such historical markers in the area, ostensibly intended to preserve basic collective knowledge of local history. The Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto is mentioned in the first sentence of the mound’s marker; it specifically mentions 1540, the year that he and his army explored the Southeast, even though they never came close to Nacoochee Valley during their expedition.The text briefly notes that there were Cherokee residents who held ceremonies here, though no temporal or cultural context is given. It concludes with a description of the white archaeologists who excavated the site—again specifying a year: 1915. There is no mention that the Nacoochee Mound was built more than three hundred years prior to Europeans’ arrival, nor that the valley was inhabited by Indigenous people up to a thousand years prior to the construction of the mound. There is also no mention that the Cherokee suffered a drastic population decline from several onslaughts, not least because of the influx of diseases from Europe. With Britain’s Royal Proclamation of 1763 following the Anglo-Cherokee War, the Appalachian Mountains were labelled an Indian Reserve, and European settlement was forbidden. Tensions between the colonists and the British flared as a consequence, and when the Proclamation was nullified with the end of the Revolutionary War, the newly independent Americans swept the Appalachians and massacred the Cherokee, who had been allies to the British. Later, with the discovery of gold and the Indian Removal Act of 1830, President Andrew Jackson enacted ethnic cleansing and exiled the Cherokee to Oklahoma along the infamous the Trail of Tears. If mentioned by historical markers, these horrors are oversimplified, reducing the Cherokee to an appearance of primitive helplessness. Cherokee society and history, to any curious passerby, is summed up in a mere couple of sentences. The Nacoochee Mound was—and remains—a sacred site, yet it has been reduced to a plinth and repurposed as an extension of a late-nineteenth-century Italianate plantation. It reinforces an all-too-familiar narrative in which white, European history is prioritized and glorified while Native American history is characterized as ancient and uncivilized.

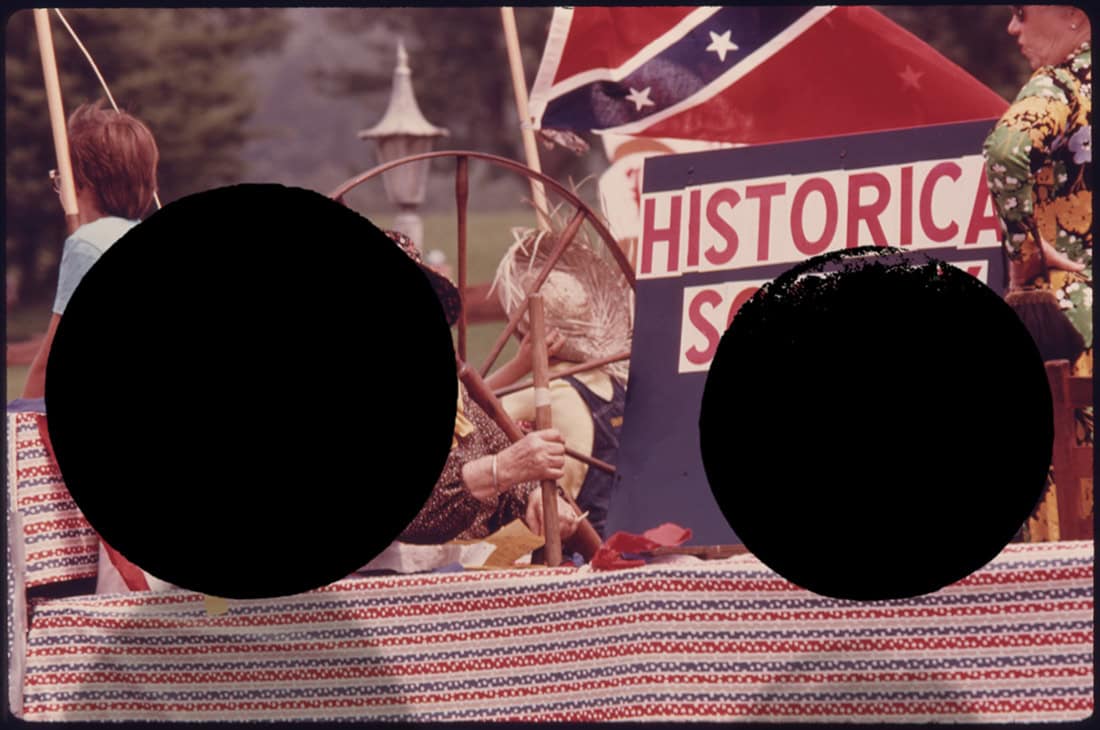

Slavery is swept under the rug, too, and replaced with a widespread defense of confederate nostalgia and exceptionalism. In this region, many generations were educated with heavily biased historical narratives in the century after the Civil War ended. They were led to believe that they were living on the scene of a stolen paradise, and that they themselves were the victims. This was the “Lost Cause” narrative, which was created in large part by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, as well as historians who wrote alternative histories just after the Civil War. They wrote their history with the explicit aim of minimizing the brutality of slavery, reframing it as a benevolent institution, and glorifying the “way of life” of the Old South. This re-education took the form of widespread commissioning of public monuments, as well as the rewriting of history books that were studied in schools all over the South through at least the late twentieth century. Not only does this contribute to a deeply confused and amnestic collective understanding of Southern history, it has also welded residents’ sense of heritage and connection to the land upon which they continue to live. About a century after the end of the Civil War—and in the immediate wake of the Civil Rights Movement—Helen was transformed into a neo-Bavarian paradise.

Just as a gazebo was built on a sacred site that has been severed from its history, Alpine Helen was constructed on a landscape formed by genocide and ecological destruction. The term Alpine Idealism was coined by a group of Helen business owners, referring to explicit limitations on the architectural form that any building in the town could take. It resulted in strict regulations that ensured architectural consistency and urban purity, even going so far as to define what the trash cans and phone booths would look like.

Given the history leading up to 1969—and Kollock’s exposure to Bavarian architecture while fighting in Germany during the Second World War—the notion of Alpine Idealism should be met with skepticism. The glib inclusion of words such as “Volk-ness” in recent blog posts on Helen’s official website also warrant some degree of critical disbelief. A play on the German word volk, or folk in English, the phrase necessarily and immediately brings to mind the German ethnic and nationalist Völkisch movement of the nineteenth century, which drew an ahistorical racial through line, connected by stories of glory and victory, from the ancient Teutons to contemporary Germans. The core narrative of the Völkisch movement mythologized Germanic heritage as racially pure and preeminent. Since Bavarian history was selected as scion for the graft, it is, of course, essential to consider the landscape and history that Alpine Helen draws from: Bavaria, and its capital, Munich, is the birthplace of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party—the nazis. While they were in power, Hitler instituted a national architectural language to symbolically exemplify nazi ideals. His architects relied on a stripped Neo-Classicism, utilitarian factories, and an exaggerated Alpine vernacular style to impose nazism’s values: simplicity and uniformity, brutality and intimidation, heaviness and eternity. The most recognized example of Hitlerian Alpine vernacular style is the Berghof, Hitler’s residence in the Bavarian Alps. The Berghof was famous for its overblown and excessively decorated interpretation of traditional Bavarian architecture: it was a caricature of the aesthetic that it adopted. Along with other Alpine vernacular buildings, the Berghof functioned as an architectural representation of the Völkisch ideology. Helen draws from Völkisch aesthetics in that it is also an exaggerated Bavarian vernacular style, aiming to artificially pull together and celebrate a communal sense of German—and Southern—heritage. Though they may seem insignificant, blog posts with titles such as “Getting Lost in the Volk-ness: Dancing in Helen, GA” point to the contemporary perpetuation of Alpine Helen’s aesthetic impulses: widespread and careless integration of white supremacist signifiers, such as the trappings of the Völkisch movement, into leisure activities. It is as important as ever today to question displays of anti-Semitism and white supremacy through architecture and visual culture. Since 2016, the Anti-Defamation League has recorded some of the highest rates of anti-Semitic hate crimes in Georgia since they began tracking in 1979, and the majority of the thirty-eight active hate groups identified by the Southern Poverty Law Center are clustered in the mountains of the northern part of the state.

Spaces and structures are never neutral, never passive. Architecture actively reinforces ideology but becomes the banal, overlooked landscape of everyday life: not least because its symbolism is left unacknowledged and government-sponsored miseducation fosters the public’s perpetual amnesia. This awareness carries particular urgency in the post-truth and highly xenophobic times in which we live. In February 2020, a draft of an executive order by Donald Trump, entitled “Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again,”was leaked. “The Founding Fathers,” it states, “wanted America’s public buildings to physically symbolize our then-new nation’s self-governing ideals.” It then disparages non-Neoclassical styles—“Federal architecture should once again inspire respect instead of bewilderment or repugnance”—and concludes, “Architectural styles—with special regard for classical architectural style—that value beauty, respect regional architectural heritage, and command admiration by the public are the preferred styles” of the United States government.

The story of Alpine Helen exemplifies how American commercialism prospers through a marriage with cultural amnesia. This system thrives when it evokes a groundless sense of nostalgia in tourists searching for a weekend of care-free leisure, providing insufficient reference and respect to previous civilizations or historical violence. Does this mean that the buildings should be torn down? Unfortunately, the solution is not that simple. But it is imperative to recognize the past for what it was and to allow its consequences to inform our decisions for the future, hopefully in ways that may repair or mitigate the damages caused by colonialism, racial violence, and—not least of all—our willingness to trade these painful historical truths for a gingerbread fantasy.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series on States of Leisure.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2020 here.