From the arrival of Portuguese slave traders in Africa in 1525 to the final abolition of the slave trade in Brazil in 1888, an estimated 12.5 million Africans were violently removed from their lands, homes, and families and forced into enslavement across the Atlantic Ocean.[1] Approximately 10.7 million survived the Middle Passage, with 388,000 of this number taken directly to North America.[2] Between these beginnings and endings was violence on an unfathomable scale, global in reach, its imprint spilling over into present days and Black diasporic communities across the world. The recent exhibition Afro-Atlantic Histories, on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., works to center the impact of forced displacement on the history of art and, thereby, the history of the world. Made up of more than 130 works of art from Africa, Europe, the Americas, and the Caribbean, and with a purview spanning several centuries, the exhibition is ambitious and heavy in both number of works and content. While it is, indeed, a difficult exhibition to traverse—the horrific and traumatic experiences that Black people endured and continue to survive remain crucial to the curatorial and pedagogical narrative of the presentation—jubilant affirmations of Black creativity, beauty, and resistance reverberate throughout the show, interrupting the repeated impulse by predominately white art institutions to center narratives of Black suffering at the expense of more nuanced, historically accurate, affirming accounts of Black life.

Organized in 2018 by a group of Brazilian curators for the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand and the Instituto Tomie Ohtake, the original intent of the exhibition was to expose the “staggering power of art made by Africans and their descendants in the Americas, as well as the response to the stimulating presence of multifarious African cultures in their midst.”[3] The Washington, DC, iteration, supervised by associate curator Kanitra Fletcher, takes up this premise, setting its smaller-scaled version to a North American audience (Black artists from North America are granted generous space in this presentation) without turning away from the international stakes and multiplicities of perspectives undergirding the Black Atlantic.[4] As Adriano Pedrosa states in the accompanying exhibition catalogue, “Histórias in Portuguese (much like the French histoires and the Spanish historias, yet unlike the English histories) can identify fictional and nonfictional narratives, written or oral ones, personal or collective, micro or macro . . . Histórias are thus distinctly polyphonic, speculative, open, impermanent: their many layers are inescapably in friction.[5] This multiplicity is echoed in the constellation of exchanges between artists with different concerns and interests from across time and space (from historical paintings by Frans Post to contemporary works by Melvin Edwards), the many genres of artistic expression and visual ephemera represented (from painting and photography to prints and film), and the multiple languages registering the gaps between cultures (all wall texts in the galleries are presented in English and Spanish).

An exhibition as vast as this one faces many obstacles and challenges, and the curators have worked hard to solve them without prescribing for the viewer a definitive story of Black diasporic experience. Divided into six sections, the exhibition orders the material by a cohort of themes as opposed to historical eras or national orientations, with juxtapositions between works from different historical eras functioning as catalysts for teasing out tensions and reverberations between artworks and cultural contexts. The section titled “Maps and Margins” opens the show, and is overtly signaled by Hank Willis Thomas’s A Place to Call Home (Africa America Reflection) from 2020: A reimagined map of the Western hemisphere made of steel polished to a mirrored shine in which the artist has replaced South America with the African continent. About the piece, a recent acquisition by the NGA, Thomas has stated, “I wanted to make a place where African Americans come from”—an acknowledgement of the difficulty in feeling “at home” faced by many African Americans whose histories were shaped and broken by transatlantic violence. The next section, “Enslavement and Emancipations,” examines the abuses of commercial slavery and the ways in which it triggered rebellion and abolitionist movements. Edouard Antoine Renard’s 1833 painting of a man in mid-swing in the midst of a slave ship rebellion is placed next to catalogue images of degrading punitive collars, runaway ads, and bills of sale, all of which reverberate with Black Brazilian artist Paulo Nazareth’s 2011 photographic self-portrait while standing in profile and wearing a fitted mask made of an animal skull next to a “For Sale” sign.

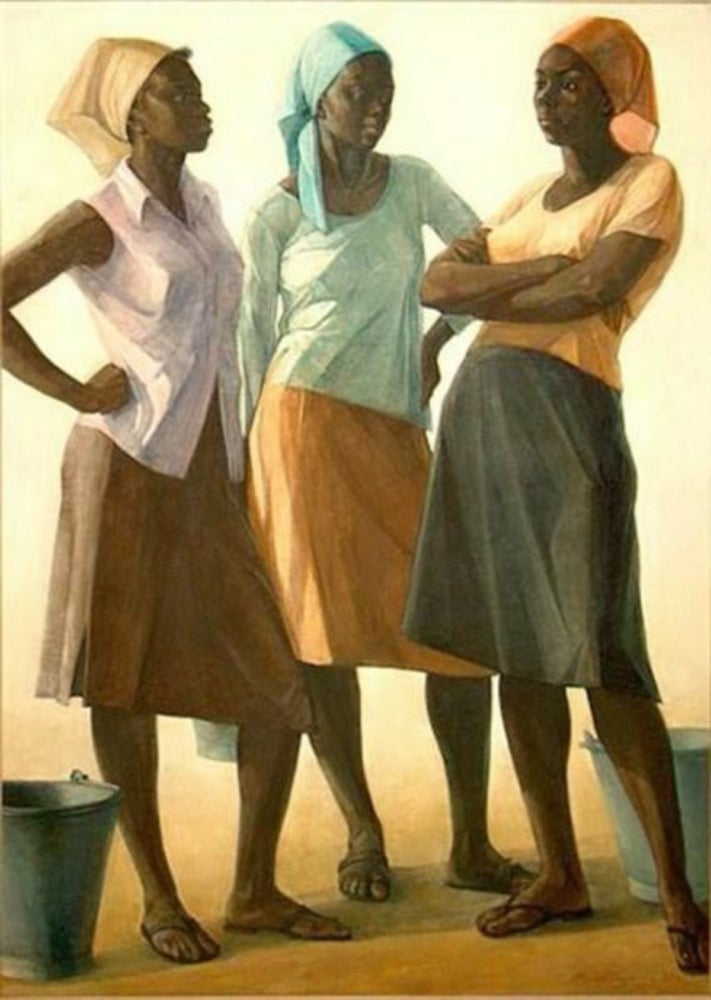

The mood shifts dramatically in the section titled “Everyday Lives,” which features more personal, private moments of Black life during and after slavery alongside highly romanticized views of forced labor and Black subservience. While Frans Post’s Landscape with Anteater (c. 1660) points to the aestheticization of Indigenous life by colonial occupiers eager to cover over the illness, violence, chaos, and death brought on by European occupiers, Barrington Watson’s 1981 painting Conversation turns the tables against an assumed white viewer and grants agency to the figures in the work instead. Dressed in workwear resonant of domestic laborers and posed in a half-moon configuration around a metal wash bucket, three Black Jamaican women take a moment to rest and talk—perhaps they are laughing, exchanging news, or divulging secrets? While the action is scaled to over life-size, not every viewer is invited into the exchange—an important reminder in this exhibition to be thoughtful about who is represented, who is looking, the many racist assumptions upheld in traditional art history, and the ways in which Black artists interrupt them.

This section is followed by “Rites & Rhythms,” which gathers works of art that speak to the significance of religious celebrations and musical expression in Black American and Caribbean culture and the ties that link these rites with African traditions. This reverberation between music and spiritual power is articulated in the juxtaposition of a lively representation of musicians playing instruments and dancing to Afro-Atlantic beats in Brazilian composer and painter Heitor dos Prazeres’s Músicos (1938) and David Driskill’s Current Forms: Yoruba Circle (1969), an homage to the dynamism inherent in West African religious practices that features the symbol of Shango—a deity of fire, thunder, and justice revered by enslaved communities in the Caribbean and Americas.

The largest room is given over to “Portraits,” and centers a 2016 mural-sized self-portrait of the non-binary artist Zanele Muholi. Titled Ntozakhe II (Parktown), it shows Muholi dressed as the Statue of Liberty, their skin darkened, their head crowned with a halo of scrubbing pads. The monumentality of the work holds space for the many different modes of self-presentation and figuration at work in the room and the ways in which Black artists from across eras continue to occupy and help redefine the genre.[6] A beautiful sightline involving Elizabeth Catlett’s Reclining Female Nude (1955), Dinga McCannon’s Empress Akweke (1975), and Frédéric Bazille’s Young Woman with Peonies (1870) opens up new places in the story of modernism and Black feminist praxis; it is one of the many visual and historical gifts of the exhibition and one I will never forget.

The final room, “Resistances and Activism,” turns an ending into a reflection on the continuing fight for freedom and liberation from oppression that remains entwined with Black diasporic histories across the globe. Textiles dominate the arrangement, with fabric standing in for social and communal binds and the labor that gives force to political action and resistance. Faith Ringgold’s story quilt Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? from 1983 transforms the racist, sexist stereotype of Black womanhood into a fully human protagonist with a history and lineage stretching across North America, India, and Germany—an intercontinental Black genealogy resonant in Alphonse Yémadjè’s dynastic history titled Emblems of the Abomey of Kings, which charts the historical leaders of the powerful West African military and commercial center of Benin. Upon leaving the exhibition, viewers must pass under David Hammons’s African American Flag (1990), which combines the color of the Pan-African flag with the pattern of the United States flag as a way of addressing the “double consciousness” of being both American and part of the Black diaspora. A proper close to an exhibition invested in keeping that historical awareness alive and present.

In addition to what is presented in the galleries and on the pages of the exhibition catalogue, the NGA has created a bevy of programs to support the exhibition inside and outside its walls, including a Black Atlantic film series, public performances by Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons and Kara Walker featuring composer Jason Moran, a special menu in the museum’s café featuring fair-trade Jamaican food, musical performances by artists from Ghana and Haiti, and walks to historical sites of enslavement in Washington, DC. Many of these programs are the outcome of the NGA’s work with two external advisory groups: the first made up of historians of African, American, and African American art; the second, of artists, community organizers, attorneys, and political collectives dedicated to working and thinking about the notion of publics. The result of this work stands as a powerful counter-narrative to the historical traditions inherent in chronological museums like the NGA, whose very origins are rooted in white supremacy and the protection and sustainment of colonial projects and whose cultural wealth would not exist without centuries of enslavement. Viewed in light of the two-year postponement by the NGA of a posthumous retrospective of American painter Philip Guston during the tumultuous summer of 2020—catalyzed by the police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and a recognition of the institution’s need to slow down and rethink its contextualization of Guston’s images of Klansmen—this exhibition points to the museum’s commitments to diversifying the collection, staff, and audience.

[1] See Henry Louis Gates, Jr. “How Many Slaves Landed in the U.S.?” The Root, January 6, 2014, published in support of the PBS public history initiative The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross for PBS, https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/how-many-slaves-landed-in-the-us/

[2] Gates, n.p.

[3] Afro-Atlantic Histories, ed. Adriano Pedrosa and Tomás Toledo (New York: DelMonico Books, D.A.P., and Museo de Arte de São Paul Assis de Chateaubriand, 2021), iii.

[4] Kanitra Fletcher’s organization of the exhibition for the National Gallery was supported by Molly Donovan, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, and Steven Nelson, Dean of the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts. The full citation of historian Paul Gilroy’s text is The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double-Consciousness (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993).

[5] See Adriano Pedrosa’s introductory essay in Afro-Atlantic Histories, ed. Adriano Pedrosa and Tomás Toledo (New York: DelMonico Books, D.A.P., and Museo de Arte de São Paul Assis de Chateaubriand, 2021), 21.

[6] See Kanitra Fletcher’s essay titled “Occupy Self-Portraiture” in the exhibition catalogue, Afro-Atlantic Histories, page 41.