Consider the lifecycle of a journal. An independent arts journal based out of Louisville, Kentucky, later expanding to include the Midwest, published art criticism, reviews, and interviews online and in a selection of printed annuals from 2017-2023. This journal was created “out of the belief that complex dialogue about art is an essential component of any healthy, equitable, and sustainable art community”.1 Ruckus was started by local arts workers, academics, artists, and writers to provide an orbital center for regional/national art dialogue with a concern for local relevance. It covered artistic responses, political and cultural events, and local events central to national conversations such as the murder of Breonna Taylor and the passing of bell hooks. Ruckus was less of an art “rag” or a “grown up” zine (saying this with deep reverence for the zine, a love Ruckus also shared).2 Akin to the lifestyle of a zine, after closing in 2023, Ruckus remains a dynamic time capsule and a silent wave of cultural expression.

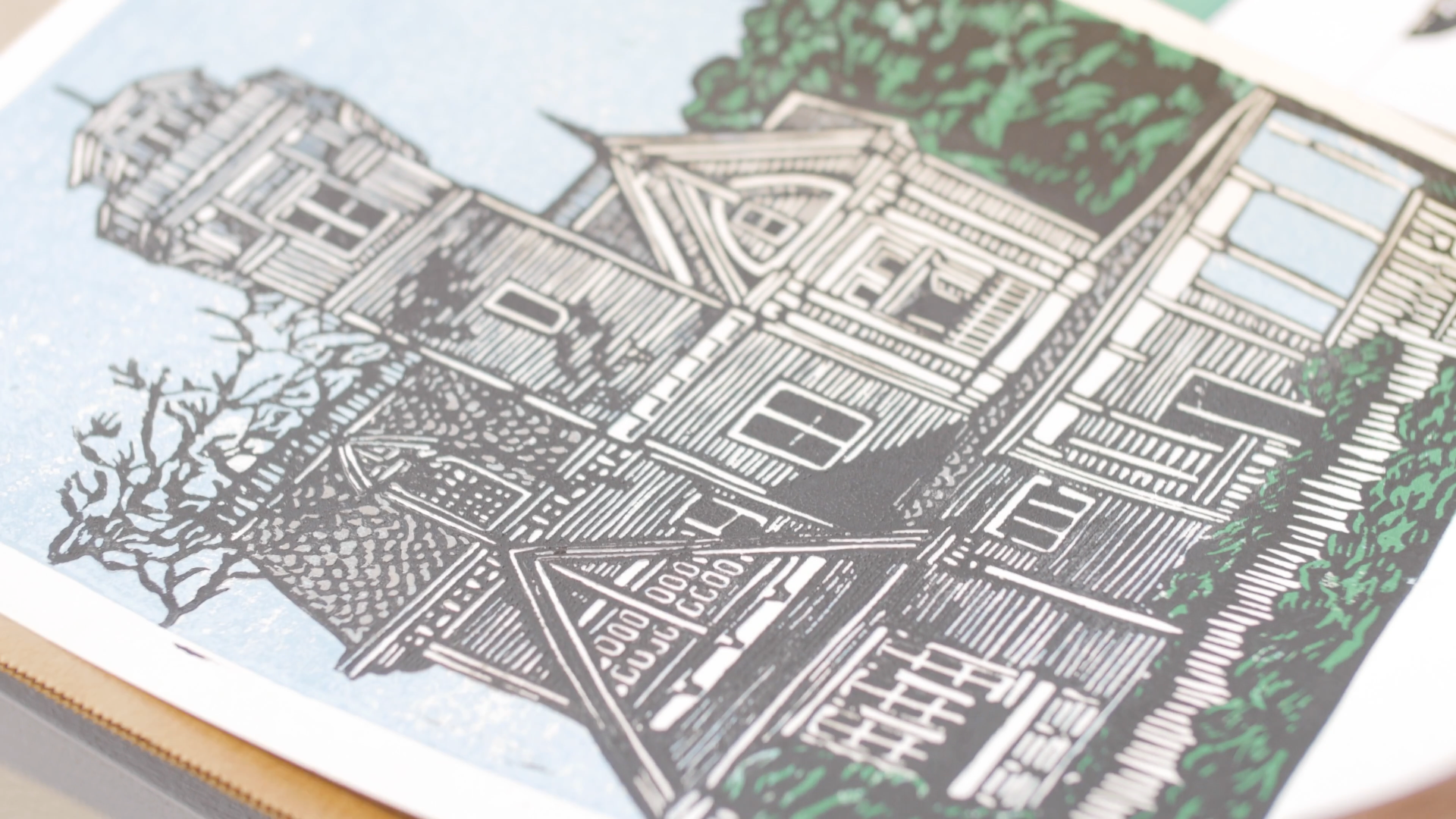

I came to Ruckus as a transplant. Even now, not living in the region, the contours in my mind of the southern Midwest and the South are Ruckus shaped. Driving over the Ohio River to interview an artist or review a show always felt destabilizing and humbling. Ruckus was born in a city of horse races. Historic buildings in Louisville still hold tobacco leaves on their exteriors and the city didn’t officially ratify the thirteenth Amendment until 1976.3 The South and Midwest are locations often spoken of as fly over, cultural monoliths, behind the times, or backwards. Ruckus alchemized even these applied conceptions into a pedestal to speak from, not about.

“Ruckus was always very conversational,” Louisville artist Thaniel Ion Lee reminded me. To honor this, what is the right way to talk about a closed publication? An eulogy? A mix tape? A thank you card? It frankly seemed impossible to do alone. So I asked contributors, artists, gallerists, critics, and sponsors from Louisville, the American South, and the Midwest to think with me about what Ruckus meant and continues to mean.

Ruckus met a need for arts journalism outside of New York or LA. When I asked about the significance of Ruckus as a publication, sponsor and gallerist Daniel Pfalzgraf said, “This region isn’t as dense in art and money as NY, LA, Miami, or Chicago, but there is still valuable and important work being done here. Now [with Ruckus closed] there is no one.”

Writer/editor Livy Onalee Snyder said, “one of the issues with art coverage in the US is that it predominantly covers art in major cities. It fuels a toxic narrative that you have to be in a major city to be seen and ‘make it’.” Ruckus addressed this reality by covering exhibitions both locally and in Indiana, Pittsburgh, Nashville, Chicago, and even when Louisville-based artists had notable shows in LA. This choice could be seen as the reflection of the ecosystems many publications exist in, one marked by the desire for limitless expansion and growth. Another way to understand the choice to expand the scope of coverage was to reiterate that the artists and art traditions with their center in places like Louisville deserve seats at regional and national tables. “I loved the way Ruckus’s inter-regional coverage juxtaposed the contemporary art scenes in the Rust Belt and the New South” said contributing critic Joe Nolan. Ruckus demonstrated a commitment to the defining of “New South(s)” shaped by Southern voices.

Ruckus addressed the South and Midwest with a dynamic plethora of journalistic techniques. “Art of Gravity”, a Ruckus-based podcast, featured discussions of the local scene and Ruckus also organized “Big Talkers”, a free panel and lecture series. The publication also partnered with Glass Breakfast, the archival project of which I am the lead filmmaker/curator, to cross-publish short one-on-one interviews with local and regional artists. Ruckus developed a microgrant for newly contributing BIPOC writers and an Editorial fellowship. Contributor Hunter Kissel pointed out Ruckus’ niche as “the blue-chips and mainstays were going to be covered anyway, and, in my opinion, Ruckus veered towards coverage highlighting that which was often experimental, lesser known, or ephemeral.” Interrogating medium as well as message can lead to more voices being heard and heard differently.

Now posthumously, perhaps Ruckus can serve as a gadfly, a stone in our boot, the sand irritating to the point of cultural nacre.

Ruckus used arts journalism to address conversations of identity, belonging, and community. Ideas of statehood and regionalism are constructions in a built environment predicated on stolen land in a country that perpetuates the dehumanization of many who live within it—ideas Ruckus addressed in a 2020 essay reimagining Louisville’s public space.4 Ruckus also published vital critiques, such as a 2022 essay that positioned craft and the writing about it as an essential tool for intersectional class struggle.5 Associate editor Noah Randolph told me that, “criticality is often used as an excuse for exclusivity, but that was never the case for Ruckus.” In an artist profile with Louisville-based artist Brianna Harlan, the publication added focus to Harlan’s crowd sourced Google survey, which created space for artists and arts workers to discuss injustice and abuse they’ve seen in their arts community and institutions. Ruckus was unique for many in that it prioritized care, strove for transparency around forms of publication labor, and held institutions accountable.

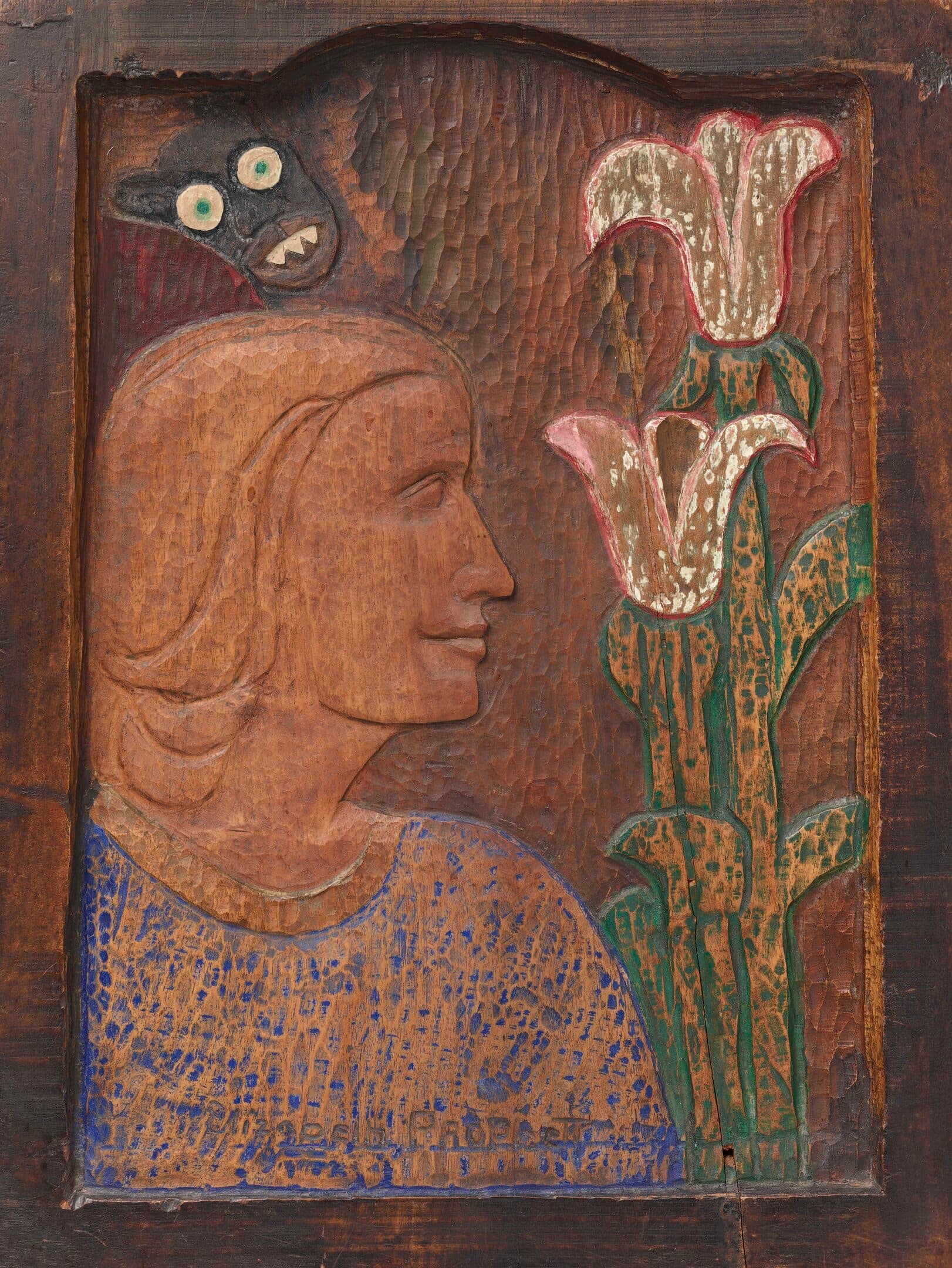

Ruckus took a chance on me. Who took a chance on Ruckus? In a farewell announcement, Ruckus editors cited the need to close being “never meaningfully able to fundraise for basic operations costs.” Local gallerist and artist John Brooks said, “People said they were so glad that something like Ruckus exists in the community—and no doubt they meant it—but were they willing to support it financially? Obviously not enough people answered ‘yes.’ At the same time, no one owes anyone anything. Ruckus’ presence in the community was meaningful, but ultimately as artists and creatives we cannot force anyone to make our ideas survive and thrive—the best we can do is hope they feel compelled to do so.” Louisville painter José Manuel Napoles reminded me that “the important thing about the publication was showing everything in the artistic arsenal that this city has, which sometimes sleeps in silence over its artists and cultural manifestations.” Now posthumously, perhaps Ruckus can serve as a gadfly, a stone in our boot, the sand irritating to the point of cultural nacre.

[1] “About Ruckus —Ruckus.” Accessed December 17, 2024. https://ruckusjournal.org/About-Ruckus.

[2] Anna Blake, “The Radical Self-Reliance of Zines — Ruckus.” Accessed December 17, 2024. https://ruckusjournal.org/The-Radical-Self-Reliance-of-Zines.

[3] Lowell Hayes Harrison, and James C. Klotter, A New History of Kentucky, Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1997.

[4] Sean Starowitz, “The Future of Public Memory: Reimagining Louisville’s Public Spaces Entrenched in the Legacy of Police Violence – Ruckus,” accessed December 17, 2024, https://ruckusjournal.org/The-Future-of-Public-Memory-Reimagining-Louisville-s-Public-Spaces.

[5] L Autumn Gnadinger. “Craft and Its Writing as Collectivized Outsider — Ruckus,” accessed December 17, 2024, https://ruckusjournal.org/Craft-and-its-Writing-as-Collectivized-Outsider.