Two hundred and thirty-six miles. The commuting length it takes to leave my home in Miami and reach one of my best friends, Kristy, at her newly bought 1950s home in the College Park neighborhood of Orlando. The Miami to Orlando pipeline is strong for many Miamians, a move Kristy and her partner Mike made mid-pandemic as work opportunities and more affordable housing presented themselves in central Florida.

A friend from early college, the silly memories of our friendship are bathed in a love for perreo, chisme, in latina daughterhood, and in siendo cabezonas. I hear of new leases signed and job promotions, in data science and in nursing, of the inevitable ups and downs that come with living together in a new community. During a birthday text check-in, a baby shower invite immediately pops up on my screen and several screaming, all caps messages later, I learn that they will welcome their newborn in the mid-summer, a season of long sweltering days, blooming flowers, and fertility.

A May maternity shoot in the Florida Springs later, I find myself in awe of my best friend’s growing belly and kicks of life felt as my hand is pressed firmly to her tummy skin; Nadia is born on the eve of Independence Day. As I photograph my dear friends amid a life chapter change, I am not prepared for the emotional shift inside myself as I witness motherhood so upfront. I think of nights still spent out and about in the city or of seeing her kayak with exhausted determination down Kings Landing. This is still my friend, one who has always wanted to be a mother, and being a mama has not changed that one bit.

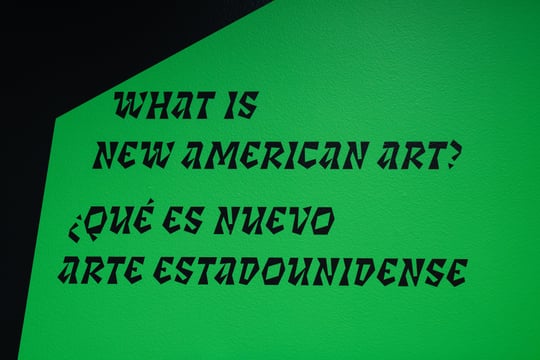

Two hundred and thirty-six miles. In my titi era, I add this distance to my Volkswagen buggy’s mileage meter more and more. Nadia is six months old, and this College Park home is now littered with breast milk pumping tools, diaper boxes, and a baby walker. In celebration of turning another year, I treat Kristy and Nadia to lunch and then an afternoon at the Orlando Museum of Art (OMA) to see the works on view in A Mother, Possibly.

Curated by Coralie Claeysen-Gleyzon, the museum’s interim chief curator, the exhibition welcomes mama, baby, and I with an intimate room of works investigating the archetype of the mother. The salon-style hanging of thirty-eight works on one of three exhibition walls ranges from photographic film stills to graphite-rendered portraits, scenes of joy and solemnity, of mothers in all their moments. Small-scale clay sculptures molded into pregnant people, laboring, or holding small children are interspersed on shelves next to framed watercolor and mixed media works on paper depicting mothers in the stages of pregnancy, breastfeeding, tending to their kids, and immortalized from the earliest stages of childcare to family-style portraits of teenagers next to their aging mother. Alice Neel’s pastel painting of a mother facing the viewer with child in arms hangs adjacent to mamans in the form of Louise Bourgeois’ big-bellied charcoal-drawn spiders. As nurturing and painful of an experience this can be for those able to bear the role, motherhood in many dichotomies and emotional landscapes can be found in the works on view.

A range of experiences are present—albeit the small scale of the collective exhibition is not entirely inclusive about the universality of motherhood. Queer mothers are not explicit in the works on view, and the focus on cisgender female body parts is certainly felt in the presentation. In some of the works, subjects hold hollowed-out placentas and uteruses as a testament to what was once there, or bear stoic, pain-stricken faces as they go into labor. In this space there is an allowance to accept and reject motherhood and the permission to show how the loss of motherhood impacts one personally as well. In one work, a mother in closed-eyed pain holding an absent, silhouetted child through the portrait on view by Titus Kaphar. Yet, there are limitations with the portrayals of Black mothers: most of the images on view were taken by white female photographers or the subjects on view are relegated to a space of loss and struggle. Black mothers as artists portraying their experience are absent in the space. There is a gravity in what it means to be a mother, and thus, curatorial conversations addressing maternity must evolve and cross borders. Assumptions are directed and imposed on mothers, on young mothers in foster care and as wards of the state, of incarcerated and undocumented mothers, on mothers without access to medical care or living through genocide, gentrification, and other systemic oppression. A, Mother Possibly only bridges the surface of this human experience, and with a white gaze heavily present even in the works depicting Indigenous, Black, and Brown mothers. The Winter Park neighborhood the museum is in is 79% white[1] and contextualizes this particular exhibition’s view on motherhood.

Inspired by German art historian Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas (1924-29)—which served to visually compile and trace the correlation of distinct imagery, symbols, and compositions across art history and cultural zeitgeist—the ebb and flow of this salon-style display provides viewers with various points of entry to the subject of motherhood. There is a correlation between the diversity of materials present and the diverse experiences of mothering. Film photography next to clay sculpture, and charcoal works on paper next to textile pieces, no two experiences of motherhood are the same. In placing both scenes of everyday joy alongside those of grief and exhaustion, Claeysen-Gleyzon assists one in being able to begin to comprehend the complexities of motherhood in all its ups and downs.

Classical sculpture and paintings of motherhood are interwoven into the contemporary in this exhibition. Since the dawn of portraying fertility and maternity through prehistoric art like the Venus of Willendorf to idealized mothers depicted in Christian art like Michelangelo’s Pieta, the essence of what it means to be a mother has rarely been left in the trust and hands of mothers themselves. The exhibition relies on the co-existence of the classical, projected notions of motherhood against contemporary realities. For example, modern depictions are muddled with a holy portrait by Cuban American twin brothers Elliot and Erick Jimenez of Maria y Jesucristo / Madonna and Child. The most interpreted mother of all time, the photograph is veiled in a hazy golden light, so dreamy it almost looks as if the print is a hand-painted fresco mirroring Medieval presentations of the iconic scene. Rather than a singular child in Madonna’s hands, twin babies flank each other at the feet of the composition—a personal touch by the twins that dismantles Western depictions of motherhood through the intersection of Cuban Catholicism’s belief in la Virgin de la Caridad del Cobre with Yoruba’s Oshun. The latter’s own birth to Ibeji—twin babies that constitute one orisha, or god—resulted in shunning as a witch despite the religion’s sanctity of birth, and later Oshun’s rejection of the twins out of her home. This refusal to mother is claimed to be the loss of the deity’s sanity, as Ibeji is later raised by Oya or Yemaya to become blessed symbolism for believing mothers today of unwavering devotion and abundance for taking the self-sacrificial steps towards motherhood.[2]

Alongside the sacrifice felt by these spiritual mothers of history, I’m drawn to the particularly Floridian sense of motherhood on view through the work of South Florida-based artists Francie Bishop Good, Peggy Levison Nolan, and Nina Surel. Photography offers a close and personal view of mothers at every stage of raising their kids, from the momentous motion of consoling a newborn in rage tears to the stages of parenting seven growing teenagers. Good’s Pembroke Pines (2009) series—titled and hailed after my own hometown suburbia—documents the field work the artist took in visiting the now permanently closed Susan B. Anthony Recovery Center, where pregnant people, mothers and their children under the age of nine, and families received care and treatment for substance abuse, transitional housing, and mental health. Without context, the mothers in Good’s photographs are alleviated of the weight and negative connotations associated with addiction and rehab, as they rear their children with tenderness. Peggy Levison Nolan’s film photographs bear a similar gravity by documenting her teenagers in the projects of Naranja and Hollywood, Florida. The ability to pay attention so keenly to her children is an act of motherhood in itself, as her images evolved into depictions of becoming a grandmother and seeing her kids become parents.

There is a gravity in what it means to be a mother, and thus, curatorial conversations addressing maternity must evolve and cross borders.

Not within the exhibition space but relevant in reverence is the posthumous exhibition that was on view in a separate wing of OMA titled NORMA: Selected Works by Norma Canelas Roth. Of Puerto Rican descent, Roth’s delicate handling of fabric patterns and beads in her work allude to maternal domesticity while also reflecting a sense of internal struggle that came with having to choose which loves to prioritize in her own life when she stopped painting altogether in 1985. Roth never called herself an artist in her lifetime, but what does it mean to mother a creative practice? Or financially sustain the livelihood of the arts through one’s economic nurturing? There is something simultaneously sad and heroic about pushing one’s interests to the side in the act of mothering—a verb that is not exclusive to guardianship.

As mama, baby, and I depart the exhibition hall and return outside to the chilly January day, I think about the small-scale nature of A Mother, Possibly in the size of its works contrasting with the magnitude in its content. To see my close friend carry her newborn under the Florida sun as we walk and talk about our plans for the next month is so simple but so grand, a seamless page turn in our friendship. As I hold Nadia, I understand more than ever the powerful reminder that a child serves in recollecting ancestry and the indefinable work of mothers. It is a reminder to lean into carefree curiosity—especially in Orlando—a city teeming with childhood in memoriam.

To purposeful mothers. To accidental mothers. To teenage mothers. To middle-aged mothers. To mothers of one. To mothers of many. To mothers of none. To mothers of artists and artists who are mothers. To mothers of the community.

A mother, definitely.

A Mother, Possibly is on view at the Orlando Museum of Art, Orlando through May 12, 2024.

[1] “U.S. Census Bureau quickfacts: Winter Park City, Florida; Florida,” U.S. Census Bureau, accessed February 29, 2024, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/winterparkcityflorida,FL/PST045222.

[2] “Ibeji,” Santeria Church of the Orishas: Dedicated to the religion of Santeria and worship of the Orishas, accessed February 29, 2024, http://santeriachurch.org/the-orishas/ibeji/.