“So, we persist. We do not give much thought to this back and forth, this act of going and coming, uprooting and transplanting. It is simply what we do. It is what we have always done, all of us, in some way. That is our history and it is our future. Ours is a collection of personal truths forever intertwined with the perplexing tendrils of shifting roots.”

Dominique Hunter, “Transplantation”1

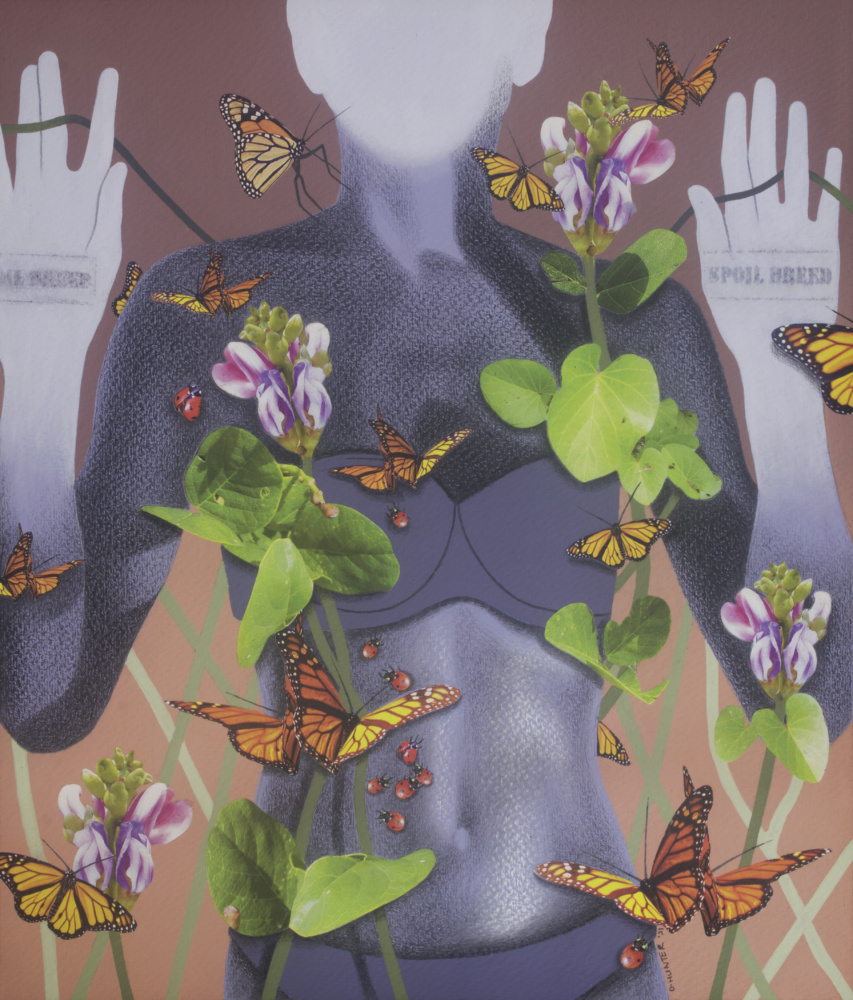

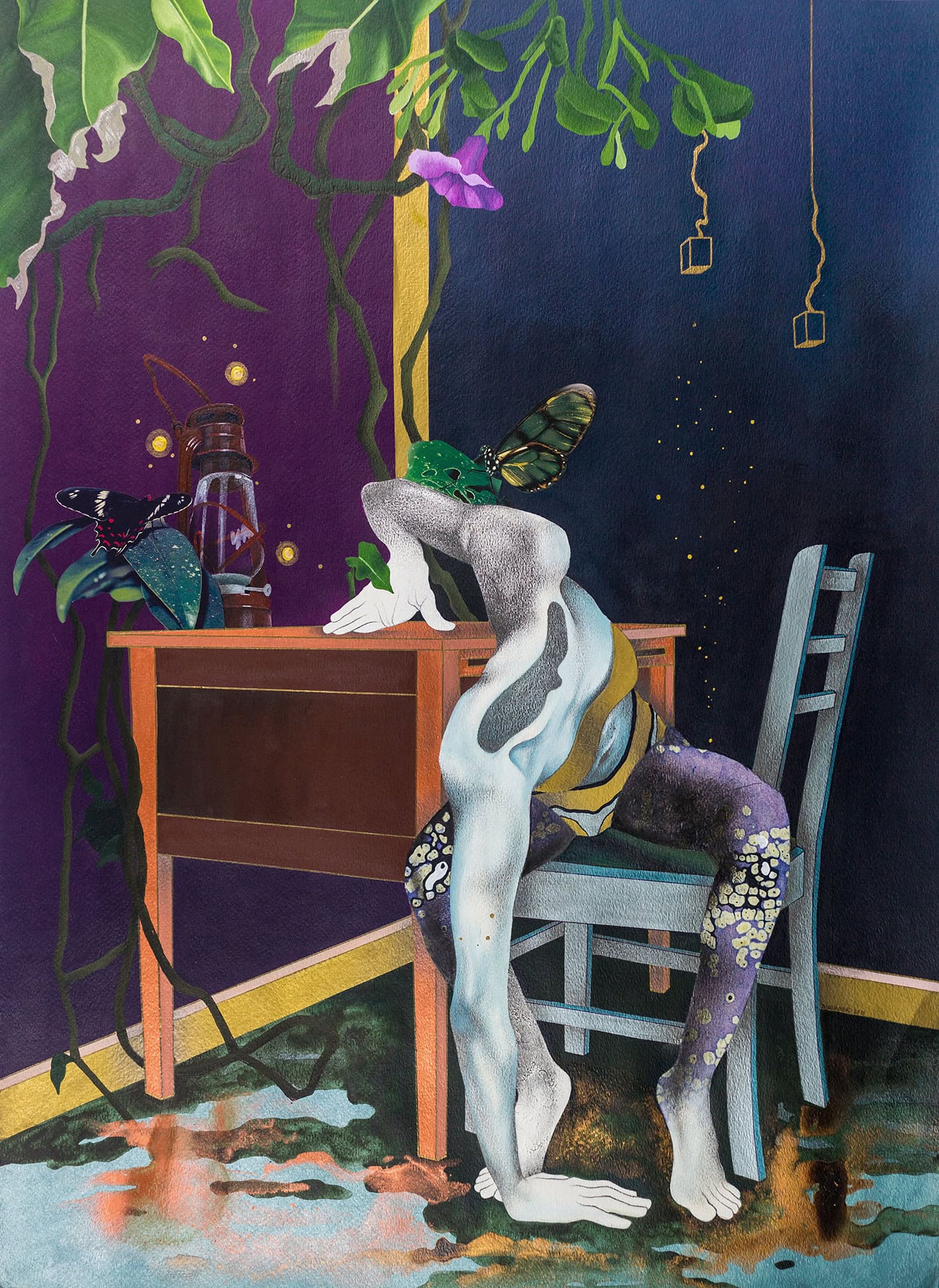

Faceless gray and white figures writhing, rolling, or relaxed in contrapposto. The liminal beings and suspended scenes in the work of Dominique Hunter act as avatars, a self-portrait, and an Eden for the yearning, heaving imaginary. She inserts fragmented parts of herself into the mixed media works: a slender feminine figure, portions of melanated skin, the visible signs of a maker slumped or draped over a desk. Hunter’s displaced depictions of self speak to the demographic of Caribbean creatives committed to living in motherlands that can feel like “otherlands,” specifically spaces of colonially rooted othering.2 As an artist living and working in Guyana, Hunter must contend with the social pressures and barriers to access that can often come with choosing to build a practice locally, within the region. This is no small task when the dominant paradigm in your local space assumes that as an artist one must move into the diaspora to find professional and creative success. Further, Hunter has had to endure the skepticism at choosing to return home after studying abroad—an experience we both share and have admittedly commiserated over as creative practitioners trying to make art and culture work sustainable in our home spaces. Her work is for those who bear the weight of remaining.

To give some context, a third of Guyana’s population lives in the diaspora.3 For Guyanese creatives, there is a particular colonial vibration to the palpable public desire to leave, to go elsewhere. As curator and academic Grace Aneiza Ali aptly put it, “migration swirls around Guyanese people.”4 For those living in the region with privilege or means, migration and movement are simply a fact of life: for medical care, education, stocking up on supplies deemed too niche to be imported. As Hunter asserts above, for those who belong to a people largely comprised of those from elsewhere, mobility and nomadism are ingrained and familiar parts of the past, the present, and an increasingly precarious future. But what of the heaviness of those who remain? Those who feel they have sacrificed access and opportunity for the sake of loyalty to the landscape? What is the weight of a heart set on staying?

To choose devotion to these spaces within the region, one’s place of origin like Hunter, is to love a place that is at once a site of pride, painful history, and perceived ceilings. To choose to be “committed to a small place” is to choose the challenging work of envisioning and building a viable future in a place where one’s ancestors were for the most part displaced and never intended to thrive, argues writer and artist Annalee Davis.5 This is part of the pain and heart at the center of many Caribbean creatives’ practices, Hunter included. Turning traumatic histories around migration, indentureship, the transatlantic slave trade, along with the socio-economic inequalities and climate crisis of the present, renders the choice to create and make as an act of love, survival, and honouring roots while not being bogged down by them.

She contends with a sort of assumed myth of possibility when it comes to migration in Guyana, one that implies ease and that life itself is somehow magically easier when living abroad. This fantasy, for Hunter, is rooted in postcolonial notions that the local is inferior to the established colonial centers in the Global north – current and former colonial powers alike. Surprisingly, for the artist and her family—given her rural, mixed-heritage background and the family’s intentional labor and care involved in belonging to this “land of many waters,”6—migration into the diaspora was not high on their list of ambitions. Still. to aspire be elsewhere is presupposed as the default desire for those homebound to Guyanese soil. In Hunter’s experience, with a mildly exasperating number of curious souls asking “why return?,” this assumption that diaspora is a thing to aspire to is disheartening at best. And with the infrastructural difficulties and local cynicism toward sustaining a regionally-based practice, to leave feels by some accounts inevitable out of frustration alone—even for those like Hunter who wish to remain in Guyana.

What is the weight of a heart set on staying?

For Hunter, smaller trips abroad for extended periods of time (for residencies, exhibition openings, commissioned projects) are her solution and adaptation to the limiting binary of the diaspora vs local artist identification she has felt restricted by. She shares: “These ‘mini migrations’ have become central to the maintenance of my overall mental health and, by extension, the integrity of every other faculty of my body. They are equally responsible for the continued growth of my creative practice as well as the expansion of my network.”7 The self-identified “maker of things”8 has chosen to stay, making mini-migrations (or transplantations) to export her creative work globally, whilst importing vitality and life into her practice and community at home.

The recurring motif of the morning glory has become a consistent presence in Hunter’s work, presenting itself for me curatorially as a plant ally. I look to the beach morning glory throughout Hunter’s work as a plant friend, laden with strategies for being one who remains. Here, the beach morning glory’s wisdom comes in three parts: rooting and routing, adaptability, and cultivating spirit.

Rooting and Routing

Using photography as a tool for thinking and considering her environment, Hunter had a memorable encounter with the morning glory in 2017 upon visiting her parent’s farm, forty-five minutes outside of Georgetown, the capital of Guyana. The flowering vine is globally recognizable, proliferating on every inhabited continent. Perhaps in coming to a lush rural space after spending much time in the heart of the capital itself, she became particularly susceptible to being moved by her reencounter with the common plant. The morning glory’s sprawling reclamation of a parapet near the back of the farm invited a deeper meditation that also led her to the interior morning glory’s coastal cousin: the Ipomoea imperati, commonly known as the beach morning glory. The roots of the beach morning glory delve deep, offering protection from coastal erosion of beach sand and dunes—increasingly important as the hurricanes plaguing the region intensify, fueled by climate crisis. The plant serves as an elegant yet hardy reminder of the importance of giving oneself strong roots. For Hunter, though the figures in her portraits are suspended in space and time, they carve out their own corner in spite of their liminality, eliciting a mobile and tenuous sense of belonging—if only clinging to available loose earth.

The plant is a tender bloom and a creeping, curious nonnative vine not intended for Guyana’s shores, let alone deep in the bush. The fact that the flower was not intended for Guyana but thrives and proliferates before the artist, along with it’s ability to exist on several other continents, becomes a fitting metaphor for Caribbean experience, as the demographic of the region is largely made of diasporas of other spaces. It takes five continents to make up the ethnic composition of the Caribbean, such a small part of the world region (continental Caribbean nations like Guyana included). For Hunter, the flower is also a symbol of her experience at the interstice of the Black and Indian diasporas. Morning glories are a constant presence for the figures in Hunter’s work, giving the imagined liminal landscapes of the compositions a sense of home regardless of their location in her painted ether and blue nonplace. The morning glory vine roots itself firmly in place, but also shoots out tendrils bravely and expansively into the unknown, routing itself toward sustenance and support from environments further afield. Hunter’s re-routing and re-grounding of the meaning within this plant, within the idea of roots themselves, helps viewers to imagine that Caribbean displacement and fragmentation is not a weakness, but a strength and symbol of survival.

Adaptability

In Hunter’s work, the beach morning glory can also be seen as a symbol of evolutionary adaptation—change born out of obligation, and finding ways to adjust to harsh environments. In this flower’s wisdom, the beach morning glory can defend itself (for example, employing a chemical response to deter insects), survive harsh briny environments, and thrive in bright sunlight. In grappling with the logistical and cultural difficulties of sustaining an art practice, Hunter—not unlike her evolving, shifting humanoid figures— was obligated to observe and adapt.

Hunter’s is a floriography in how to evolve with and nurture a place into viability. In the artist’s painted liminal space, bodies reach longingly: for light, for sustenance, for support and data from their environs. Just as the searching vine does, they find themselves covered and integrated with its tendrils. The figures are reclaimed by the land, so that it becomes an irremovable part of them—just as the landscape is assimilated into the hearts of those from small places. Guyana is by no means small in land mass; smallness here imparts a sense of otherness, of not being a big player on the global stage. Nonetheless, adaptable morning glory, adorned spirits, like that of Hunter and the hybridized beings in her work, remain in the landscape to the point of assimilation. They keep their homeland’s soil holding firm through the storms. Similarly, those in diaspora hold their earth close to their hearts, displaced but also mobile—adapting and hybridizing as a way to till a home away from home. Hunter’s work speaks to those on either side of the diasporic flow who seek change and upward growth.

Grounding the visuals of her work is also the intentional practice of proverbially watering the ground around her, a fertilizing of one’s roots. Encountering the unfortunate reality that many creatives in the region face around making a living from their work, Hunter takes the beach morning glory’s lessons in adaptability into her expanded practice, fertilizing the soil in Georgetown so that it might bear future fruit. Like many Caribbean creatives, she is not unfamiliar with being multihyphenate: artist-writer-educator. Hunter teaches at the E. R. Burrowes School of Art as a means to supplement and feed her creative work, while offering guidance, support, and strategy to younger generations.

She is part of a lineage of care, including prominent local artists like Stanley Greaves and Burrowes, her institution’s namesake. Hunter’s contributions to community building with the Guyana Women Artists Association, as well as her art writing and educational work, are all displays of love and of giving water to Guyana and its ghosts. Working to shift the culture away from colonially rooted ideals is foundational to her life’s work. Her expanded practice speaks to the cultivation of home by way of adapting to one’s circumstances. Adaptability wisdom can mean adjusting to and resisting the commonly understood capitalist desires associated with the arts. It can mean opting instead to find one’s survival in collective care and reciprocity, tending to a space so that it can hold you and those you love.

Cultivating Spirit

Hunter’s morning glory brings with it many meanings, both metaphysical and metaphorical. These blooms carry wisdom for those navigating what it means to love and remain in the Caribbean, even when it can feel at times like loving at a detriment to oneself. But in learning to evolve and adapt to harsh environments and rooting from a place of stability for self and the collective, Hunter’s morning glory strategies work to cultivate a formidable strength of spirit. They unfurl themselves across the threshold of possibility and purpose—plant medicine for healing postcolonial woe.

Hunter looks to the morning glory as a metaphor for Guyanese and Caribbean experience.9 Within this is the trauma and weighty history contained in the idea that the majority of people living in the Caribbean, as Hunter recalls, “were never meant to be here, and yet here we are”—just like the nonnative morning glory in the Guyanese landscape.10 The flower’s wisdom for a strong spirit, in this context, is the freedom to be found in recognizing that the shared landscape can be a collective platform for self-realization on one’s own terms. In a landscape scarred by sugar plantation and the colonial histories of enslavement and indentureship, to take action and build out safe and intentional space— in the social landscape but also one’s spiritual inner landscape—is an act of love and decolonial care, of ancestor work.

These blooms carry wisdom for those navigating what it means to love and remain in the Caribbean, even when it can feel at times like loving at a detriment to oneself.

To remain, in Hunter’s context, is to commit to a series of deaths and rebirths, to remain in the liminal state of being at the precipice of potential, of something yet to be. Possibility is the inspiration and excitement that fuels all manner of (r)evolution, innovation, and plant-led reclamation. To view the Caribbean conception of home, as Ali suggests, “of homeland as both fixed and unfixed, a constantly shifting idea or memory, and a physical place and psychic space,”11 then home for the Caribbean artist can be imagined as a fluid space of becoming, one that shifts and feels inherently Caribbean simply because of that shifting and lack of fixity. This is understandable, considering she is a distillation of hundreds of years of migrations that went into the region. Hunter’s mini-migrations elsewhere help her break through the perceived stagnation of fixed thinking and low ceilings in her own space. At the same time she is able to commit to home more organically and fluidly, in a way that allows for less resentment and combats feelings or local ideas of being stuck at home Guyana.

It is “a miracle that we have artists at all” in the Caribbean, says Davis, many miracles folded into one in fact. It is astounding that Caribbean people—spanning diverse linguistic regions and graphically horrific histories of struggle—have and continue to find ways to recover the landscape—social, environmental, spiritual. And that they reclaim selfhood, joy, and community, producing incredible figurative blooms in their respective creative practices. The work of investigating, challenging, and exploring alternative senses of self within the Caribbean’s diverse landscapes is the work of making a true living. To root oneself, to tend these tender seeds of belonging, is to proclaim that to be Caribbean is to use hardship to germinate stronger ways of growing and being. To make home intentionally in a landscape that was never intended for one’s survival is not as simple as resilience, it is divine alchemy.

[1] Epigraph from Dominique Hunter, “Transplantation,” in Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora, ed. Grace Aneiza Ali (Open Book Publishers, 2020), pp. 83–90.

[2] Grace Anieza Ali defined “otherland” as following: “motherland, the place of birth; and otherland, the space of othering.” Ali, “Introduction: Liminal Space,” in Ali, Liminal Spaces, p. 13.

[3] Guyana’s diaspora is an estimated 36.4% of the nation’s population – Guyana’s large diaspora an asset to country’s transformation – Guyana Chronicle. (2022, November 14). Guyana Chronicle. https://guyanachronicle.com/2022/11/14/guyanas-large-diaspora-an-asset-to-countrys-transformation/.

[4] Grace Aneiza Ali, “States of Mobility: Those Who Leave and Those Who Are Left,” interview by Celeste Hamilton Dennis, Contemporary And, March 24, 2020, https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/those-who-leave-and-those-who-are-left/.

[5] Annalee Davis, “On Being Committed to a Small Place | 13°/59°,” in On Being Committed to a Small Place (San José, Costa Rica: TEOR/éTica, 2019), p. 165.

[6] “Indigenous peoples inhabited Guyana prior to European settlement, and their name for the land, Guiana (“land of water”), gave the country its name. Present day Guyana reflects its British and Dutch colonial past and its reactions to that past.” See B. C. Richardson and Jack K. Menke, “Guyana.” Encyclopedia Britannica, August 2, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/place/Guyana.

[7] Hunter, “Transplantation,” p. 89.

[8] Hunter defines herself in interview as a “maker of things”, intentionally borrowing the term from fellow Guyanese artist Stanley Greaves. (Stabroek News, “‘You Have to Define Yourself’ Says Artist Stanley Greaves,” December 6, 2014, https://www.stabroeknews.com/2014/12/06/news/guyana/define-says-artist-stanley-greaves/.

[9] Dominique Hunter, interviewed by author, August 4, 2024.

[10] Dominique Hunter, interviewed by author, August 4, 2024.

[11] Ali, “Introduction: Liminal Spaces,” p. 4.

[12] Davis, “On Being Committed to a Small Place,” p. 165.

This essay is a feature release of Burnaway’s 2024 theme series Crush.