Chattanooga, astride the Tennessee River and the Georgia state line, is usually associated with business and tourism, a potpourri of Moon Pies, Coca-Cola, Rock City, and Civil War memorials. But now, not far from the historic Chattanooga Choo-Choo, an ambitious cadre of young visionaries is planning something new: an enormous cultural, educational, and artistic space called Stove Works. Their goal is to raise the arts consciousness of not only Chattanooga but the South as a whole.

The project is the brainchild of Charlotte Caldwell, an avid lover of contemporary art who describes herself an “artist facilitator.” Caldwell has a degree in arts administration from New York University and is the former residency director at the Wassaic Project. A Chattanooga native, she’s also a member of one of the city’s philanthropic families – named Chattanooga’s Outstanding Philanthropists of the Year by the Association of Fundraising Professionals in 2004 and prominent contributors to the city’s Hunter Museum of Art. She’s been joined by artist Mike Calway-Fagen, whom she hired away from a tenure-track job at the University of Georgia to help develop the Stove Works residency program and curate exhibitions. Calway-Fagen is also serving as an adjunct instructor at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

Stove Works is a 75,000-square-foot facility on East 14th Street, between the city’s Southside Historic District and Highland Park, an industrial area that’s starting to become more focused on culture and shopping rather than manufacturing. The property had once belonged to Caldwell’s family, long-time manufacturers of stoves in Chattanooga — including Modern Maid, a brand that at one time sold in all 50 states. Caldwell bought the property for $750,000 in March 2017 after getting wind of the sale from commercial realtor Jack Martin of Fletcher Bright Co., a family friend.

When building renovations are completed, at an estimated $3 to $5 million, Stove Works will house an exhibition space, an artist residency program, restaurants, and shops. Caldwell declined to discuss the specifics of project funding beyond saying that it’s being paid for by traditional construction lending and a series of public/private partnerships.

Caldwell prefers to focus on what Stove Works might do for arts and arts education in Chattanooga and the South, and not on her family’s connections (and which of those, if any, are helping to fund the project). But such resources give Stove Works an edge, and access to funding seems to be a critical factor in getting the project off the ground.

Most of the Stove Works space – 50,000 square feet – will be occupied by commercial tenants. The remaining 25,000 square feet will include gallery space and a live/work area on site for artists. According to the realtors’ brochure for the site, “The goal of this development is to build a creative space and destination for the immediate community, greater Chattanooga, and the region — with the nonprofit serving as the anchor of the complex.”

The ultimate goal is that income from for-profit enterprises – enterprises like the restaurants that are already springing up in the area – will support overhead, with additional fundraising going directly to artistic programming. Stove Works is currently in conversation with a brewery and restaurant and have commitments (though not signed leases) from a bookstore, a design studio, and a coffee shop. And that’s only possible because, at least so far, Stove Works has been able to move forward with construction plans using the combination of construction lending and partnerships Caldwell described. She’s also put together a young board – all under 40 – with an eye toward developing a long-term passion for contemporary art among the city’s future leaders.

Once construction is complete, early to mid-career artists will live on site and display work in a dedicated exhibition area. Living and working space will be provided, and while there won’t be a stipend initially, it’s in plans for the future if they can garner enough support from community sponsors, grants, and individual contributions. There will be eight live/work spaces for visiting artists and one for a residency fellow, a recent graduate from one of the area’s colleges or universities. Six studios will accommodate practicing visual artists and the remaining two will be dedicated to writers, curators, and other non-object-based artists. Residencies will last for one to three months, with the exception of the fellow, who will remain for six months. Applications will open in the spring of 2019.

Calway-Fagen will oversee the artist residencies, using his personal experience. “One of the things I brought to the table was studio design in relation to living space,” he says. As a result, “each artist at Stove Works will have a 400-square-foot studio, and the studio will be really pristine. Lots of natural light.” Each artist will have living quarters separate from the studio, allowing for privacy, along with communal space. Caldwell is adamant about not offering art work for sale. “At no point will Stove Works engage in the sale of art work,” she says. “In the case of an interested collector, we will simply point them in the direction of the artist.” The goal is to allow the exhibition area to function as a museum and educational space rather than a for-profit gallery. Longer term, there are plans to include a black box theater, art library, and classroom. Because of the extent of the renovations involved, Stove Works is not scheduled to open until the summer of 2019. Current fundraising efforts are not focused on the building itself but on additional funding for salaries, and longer term for exhibitions and programming.

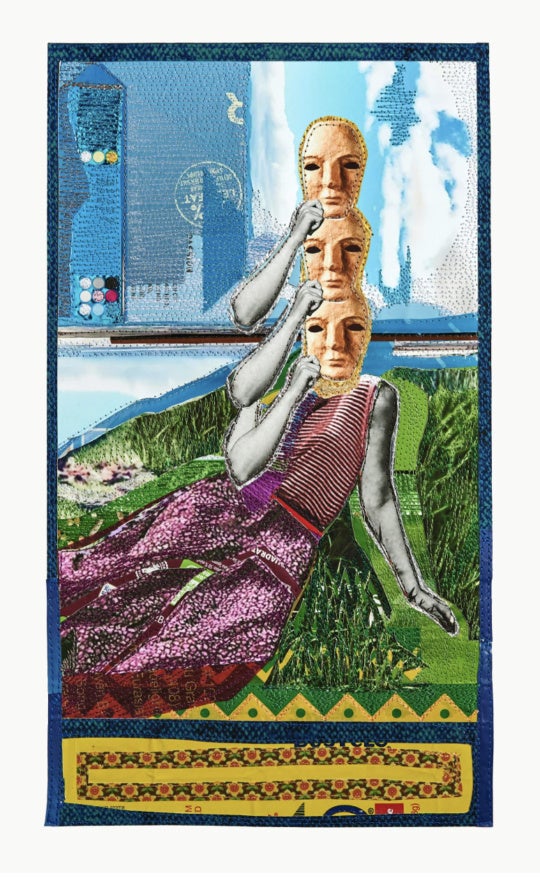

While the space undergoes renovation, there will be several exhibitions, including a four-week show called “Land and Sea” this August and several two-week exhibitions throughout late 2018 and 2019, intended to “call attention to the immensity of the world.” Calway-Fagen and Caldwell are still in conversation with artists to determine the final line up. The series will be free and will be held at various locations throughout the city in part, Caldwell says, “to introduce our programs and style to a wider audience.”

The overall vision for Stove Works might best be described as changing the landscape of how contemporary art is received in the South. “I want to bring the Southeast out of whatever visual narrative it’s been locked into,” Caldwell says. “Artists that are practicing at a conceptual level, whose work isn’t just about an object, but whose work explores complex issues — I want to expose Chattanooga to that visual language and provoke people into conversation.”

Talking to Caldwell and Calway-Fagen, it’s easy to believe that the project of transforming the artistic landscape of the Southeast isn’t as Herculean as you might imagine. Both are energetic and optimistic, motivated and smart. Both Tennessee natives, they see artistic promise in the region and can rattle off the names of artists, professors, and arts groups that have flourished in Nashville, Asheville, Charlotte, Atlanta, and Birmingham – a constellation of cities with Chattanooga as its geographic center. And both are the kind of people who seem to be surrounded by dozens of friends with connections to the arts scene across the Southeast and deep roots among those who can help make things happen.

In fact, Caldwell’s ties in the community – specifically, her family friend Jack Martin, the commercial realtor who sold her the property – connected her back to the family’s old building. When the building originally went on the market, it sold in a day. As soon as she learned of the sale, Caldwell called Martin and asked if she could rent a space for her arts organization. When that deal fell through, he called her back.

“That building is going to go back on the market,” Martin said. “Do you want to be a tenant?”

“No,” she said. “I want to buy it.”

It was an instinctive response, Caldwell says. She wanted to own the building, and had actually thought of using the name “Stove Works” for the arts organization she’d wanted to start for years. “I left Wassaic to start Stove Works,” she says. “When I moved to New York, it was with the intention of absorbing as much knowledge as possible and then returning to the Southeast. If Wassaic had been in Tennessee, I might never have left. I didn’t expect to return to my hometown. But when I was scanning the Southeast for places to get this program started, Chattanooga came out on top. It has the right ethos. It is constantly reinventing itself. And I love that.”

Caldwell believes that in buying the property, she will be able to circumvent some of the pitfalls that beset arts organizations at all stages, especially the need to show art that meets market demand or the latest trend in grant funding. By owning the building, Stove Works also hopes to avoid being driven out of their space if – or probably when – gentrification overtakes the neighborhood, as it’s beginning to do in nearby areas.

Both Caldwell and Calway-Fagen are keenly aware of the racial and economic politics of gentrification, and a large part of our conversation was devoted to how they could be good neighbors to current long-term, mostly African American residents. They’ve joining the neighborhood association and having been discussing needs and concerns, such as the loss of community space, with their neighbors.

Still, Caldwell says, there are many forces beyond their control at work. “With the rapid pace of development in the city,” she notes, “it would just be a matter of time before we would not be able to afford rent. We would be way more beholden to fundraising and to grant makers and to donors of all varieties.” Instead, they hope to control at least some of that development themselves.

All this started in a bar in Nashville (Mike’s home town) around a decade ago, when Charlotte and Mike first met. “It was one of these weird random conversations,” Mike says, “Oh you like art? This guy likes art. You should meet this guy.” They discussed the state of art in Tennessee and regionally, Mike says, and “what could be done to stoke the smoldering flame that never seems to quite catch on.”

For Stove Works, success will mean turning this smoldering flame into a real fire, into what Caldwell calls “a catalyst for art in the South.” “Tennessee doesn’t have a large contemporary arts scene, which is incredible to me,” she says. “There isn’t a lot of governmental funding for artists. In the state of Tennessee there is very little funding for individual artists and the way that art communities are coping with that is by creating these nonprofit residencies and arts organizations. I want to be part of that energy.”

At this stage, of course, it’s impossible to tell whether or not this energy is pouring into a pipe dream or whether Chattanooga is finally getting that special combination of philanthropic interest and enthusiasm for contemporary art that fuels artistic centers like New York. But Charlotte herself is a firm believer: “This has to succeed,” she says, over and over again, throughout an hour-long conversation. “And it will. I know it will.”